Neoliberalism and Detroit

In the 1950s, Neoliberalism emerged as a political and economic theory based on the principles of deregulation, free markets, free trade, privatization and strong property rights.[1][2] The role of the government, according to neoliberalism, is to implement policies that allow businesses and corporations to operate according to these principles.[2] While some cities around the world have benefited economically from implementing neoliberal policies, others such as Detroit, Michigan, have suffered the draw backs.

The implementation of neoliberal policies among other events allowed the automobile industry, the backbone of Detroit’s economy, to grow outside of the U.S., leading to the decline of Detroit. Some argue that “Detroit rose and fell with the automobile industry.”[3] Since the beginning of the decline, Detroit has experienced a significant increase in crime rates due to unemployment and poverty. Over the decades, this has led to numerous social issues, most of which affect the low income families, particularly the African-American residents.

The Rise of Detroit

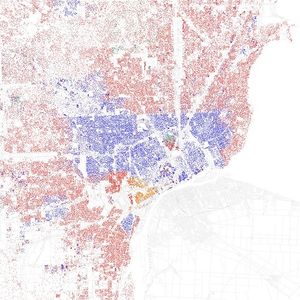

Red is White, Blue is Black, Green is Asian, Orange is Hispanic, Yellow is Other, and each dot is 25 residents.

Throughout the 20th century, the city of Detroit built its reputation as “The Automotive Capital of the World”.[4] In 1903, Henry Ford founded Ford Motor Company, and by the end of the decade, he revolutionized industrial work by introducing two innovations: the assembly line and the “five-dollar day”.[5] The former has improved industrial productivity, while the latter kept turnover rates low. Since then, the automobile industry grew significantly, and some of the most well-known automobile companies, such as General Motors (1908) and Chrysler (1925), were founded and also established their base in Detroit. These companies complied with demands of labour unions for the 8-hour day, 40-hours a week limit, making assembly line work more attractive for people.

Demographic Changes

This increased immigration into Detroit, primarily from Southern U.S. The population of Detroit increased from 285,000 in 1900 to nearly two million by 1950,[3] making Detroit the fifth largest city in the U.S. in 1950.[6] During this time, the automobile industry employed almost one in every six working Americans directly or indirectly, and Detroit was its epicenter.[6]

Segregation

White Americans made up more than 80% the population during this time. While some black Americans migrated to the North earlier, majority of them moved after 1940.[7] By 1945, Detroit’s lower east side, Black Bottom, was home to more than 98% of the African-American residents; very few of them lived in the suburbs, where most of the white Detroiters lived. This gave the city an interesting character that was purely based on racial segregation, which is well documented by Heather Thompson.[7]

Racial Discrimination

In addition to segregation, the African-Americans were also discriminated when it came to home ownership. Of the 98% African-Americans in Black Bottom, only 8% owned their home, while the rest were renters.[7] The problem was that black communities had less access to mortgage programs because “racially diverse neighbourhoods” were deemed “risky” by the federal policy.[3]

Decline of Detroit

In the 1970s, the automobile industry began to decentralize away from Detroit and the U.S. as other countries adopted neoliberal principles of market liberalization and free trade to some extent. This increased international competition for Detroit’s manufacturers. German and Japanese automobile companies, in particular, expanded into many markets rapidly as they were able to produce more quality cars at lower cost. The increased competition forced Chrysler into bankruptcy, while Ford and GM experienced financial difficulties.[3] As a solution, these companies relocated and offshored some of the manufacturing to other states and countries with lower labour costs and regulations.[7] Further technological innovation introduced more machinery into the assembly lines.[3] These factors resulted in mass job losses in the automobile industry in Detroit.

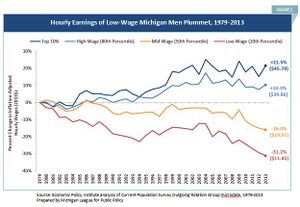

Declining Middle Class

Employment in manufacturing jobs in Detroit decreased from 214,000 in 1950 to 104,000 by 1990.[3] There were less employment opportunities, which forced many middle class residents (mostly white) to move out of the city for opportunities elsewhere because they could afford to move. A declining middle class created a polarized Detroit. The poorest families and individuals, those dependent on welfare that was funded by taxes, were left behind. Thompson argues: “It was when Detroit lost its white population, tax base, and political support that its future was doomed.”[7] This is because the whites had better jobs in the industries while the blacks still faced racial discrimination in employment.

Crime and Incarceration

Due mass emigration, numerous buildings were left abandoned, while “[more] than 20 percent of Detroit’s largely black population lived below the nation’s poverty line, and the infant mortality rate in the city had risen to 24.2 percent” by 1980.[7] These social issues create the foundation of crime, and tend to have generational effects. Drug trade emerged on the streets as a result, and was followed by worse crimes including homicide.

Strict drug laws in the U.S. make it very easy for relatively young people to be incarcerated. Combined with privatized prisons due to neoliberal policies, there is an entire industry built around the prison system and profits from it.[8] In a study, Peck and Theodore claim that about 68% of prisoners in some prisons are African-American men, of which “48% are aged under 31 and unmarried, while 46% have one or more children; 40% had been incarcerated for drug offenses.”[9]

Drug offenses include something as minor as the sale of marijuana, but it earns them a criminal record, which makes it more difficult for them to find employment once they are released. The lacking of decent economic opportunities pushes a former drug offender back to the streets for extra cash, but they also run the risk of being arrested again.[9]

Gendered Issues

Incarcerated men with children and dependents cannot supply and support their families, so the pressure falls on the women in the community. The problem, however, is that in addition to gendered discrimination in employment (i.e. earning them less than men on average), most of these women also experience racial discrimination from employer preferences when they try to get employment. Without adequate amount of time spent on the children, the children grow up to repeat the mistakes of the previous generation, forcing the entire community to struggle again, thus the generational effect.

Neoliberalism has created a Detroit where African-Americans are completely marginalized.

References

- ↑ Palley, T. (2004). From Keynesianism to Neoliberalism: Shifting Paradigms in Economics. Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved from /http://fpif.org/from_keynesianism_to_neoliberalism_shifting_paradigms_in_economics/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Sugrue, T. (2004). From Motor City to Motor Metropolis: How the Automobile Industry Reshaped Urban America. Automobile in American Life and Society. Dearborn: University of Michigan.

- ↑ Woodford, Arthur M. (2001). This is Detroit 1701–2001. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2914-4.

- ↑ Dassbach, C. H. (1991). The Origins of Fordism: The Introduction of Mass Production and the Five-Dollar Wage. Critial Sociology, vol. 18, 77-90.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sugrue, T. (2007). Motor City: The Story of Detroit. Retrieved August 05, 2016, from http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/politics-reform/essays/motor-city-story-detroit

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Thompson, H. (1999). Rethinking the Politics of White Flight in the Postwar City. Journal of Urban History 25(2), 163-198.

- ↑ Bonds, A. (2006). Profit from Punishment? The Politics of Prisons, Poverty and Neoliberal Restructuring in the Rural American Northwest. Antipode, 38, 174–177. doi:10.1111/j.0066-4812.2006.00571.x

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Peck, J. and Theodore, N. (2008). Carceral Chicago: Making the Ex-offender Employability Crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 251–281. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00785.x