Medicalization and the Female Body

What Is Medicalization?

Medicalization is when a nonmedical condition or problem is described and understood in medical terms and responded to with medical interventions. The key in identifying medicalization is “that an entity that is regarded as an illness or disease… [becomes] defined as a [medical problem]” (Conrad, 2008).[1]

Advantages and Disadvantages of Medicalization

Medicalization can lead to both positive and negative consequences. Discoveries in medicine, sanitation, and health care combined with greater understanding of the human body and brain functions have resulted in advances such as the eradication of some diseases, reductions in infant mortality and maternal morbidity, fewer surgical deaths, and increases in lifespan. Classifying certain conditions as either medical or mental health disorders allows for increases in funded research, treatment options and access to insurance.[2]

Medicalization has disadvantages as well, specifically that it can be used as a tool for social control.[3] When natural variations in everyday life and human experience—such as biological differences between men and women, or differences in inclinations and self-expression—are medicalized, societal and even legal implications may follow.[2] [4]

Gender is a factor that must be considered when looking at the topic of medicalization and how it may be used as a form of social control.[1] Women are more likely to experience “disproportionate pharmacological or surgical interventions,” and to be prescribed psychotropic medication for legitimate medical problems. [4] “Through prison, psychiatry, the institution of marriage, medicine, tranquilizers, electro-convulsive therapy, ‘premenstrual syndrome’, gynaecological surgery and laws (e.g. abortion and new reproductive technologies), society pathologizes and criminalizes women’s bodies and women's minds” (Frigon, 1995).[5]

The Female Body as a Site for Control

Throughout western history, particularly in patriarchy-dominant societies, women’s natural life processes have often been seen as different from men’s and therefore inferior and deviant. The concept of woman as deviant has been especially connected to differences in female biology, such as in reproductive processes, sexuality, and the endocrine system. Because it is specifically the female body that has been seen as both the site for and the cause of deviance, the female body itself became the site for “treatment” and subsequently the site for control.[6] [4]

Medicalization provided social and legal mechanisms for establishing this control over women’s bodies and lives, resulting in denial of women’s agency and human rights. Formal medicine has been a largely male-dominated practice and profession throughout much of western history. Consequently, medical conditions or diagnoses were in many cases determined and treated by men, further entrenching gender inequality in women’s life experiences.[4]

Examples from History: How Medicalization Has Disempowered Women

Following are four examples of how women's natural life processes, responses and states have been medicalized throughout history, impacting women's autonomy.

Hysteria

The ancient Egyptians and Greeks believed that hysteria was caused by a “wandering uterus” and therefore was a woman’s disease; the prescribed cure was marriage and sexual activity with men. During the Middle Ages, women diagnosed with hysteria, or other illnesses of undetermined origin, were considered to be possessed or witches. As a result, thousands of women were tortured or killed.[7]

In 17th century America, the Salem witch trials (1692–1693) centred around an episode of mass hysteria. Twenty people were officially executed, 14 of whom were women. Across Europe and in North America, accusing women of witchcraft continued until at least the 18th century. It’s estimated that tens of thousands of women were killed as witches between 1300–1800.[8]

Hysteria and related ailments continued to be a frequent diagnosis into the early 20th century.[7] It was still believed to be primarily a woman’s disease and a chronic condition. Instead of torture and death, orgasm became the method of choice for providing relief. Physicians were often involved in providing this “treatment,” whether through manual or mechanical stimulation.[9] In addition to the controversial nature of hysteria as a legitimate diagnosis, this is also an example of medicalizing women’s bodily functions and sexual pleasure; it was highly invasive and would certainly be unethical today.

Self-Expression, Emotions and Mental Health

Until the 20th century, societal and cultural norms within the western world emphasized that a woman’s place was in the home, as a homemaker, wife, and mother. A “good” woman was a demure woman—quiet, submissive to her husband, devoted to her family. She did not display emotionality or offer opinions. Women who expressed their natural emotions (sadness, anger, joy) or interests or inclinations (sexual desires, education, politics, independence) were considered ill or dysfunctional. Treatments may have included use of smelling salts (“taking vapours”), bed rest, various herbal remedies, “hysterical paroxysm” (orgasm), and abstinence from mentally stimulating activities, such as reading.[10][7]

The expression of women’s emotions continues to face regulation and medicalization today. Responses that may be perfectly normal such as crying, an angry outburst, disinterest in sex, unhappiness, or other expressions of distress are pathologized and may be perceived as symptoms of an underlying mental health disorder, such as depression.[11] [12]Women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with depression. Higher female to male sex ratios are also seen in various anxiety disorders, such as Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, and Specific Phobia.[13]

A related societal construct is that women are not only more emotional than men but specifically, that they are more emotionally unstable. It is a common misperception that the cause of women’s emotionality is their unique reproductive hormones. While studies indicate correlations between women’s hormonal fluctuations and their social and relational experiences, there are no correlations between hormones and depression.[11] [12] Prescribing anti-depressant medication, such as SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors), is the common treatment response for mood or anxiety disorders, even though anti-depressants generate only weak treatment outcomes for disorders such as depression.[13] A reliance on pharmacological interventions ushers in another topic of concern: that the medicalization of women’s normative life responses opens the door for commercialization of the same.

Reproductive Processes

During the Victorian Era, pregnancy and childbirth also began to move out of the home and into a medicalized environment. This could be seen as an extension of the notion that the home, as a woman’s place, was one of propriety and cleanliness. Childbirth, by contrast, is messy and can be unpredictable.

Up until the mid-20th century, women were sometimes so heavily sedated during childbirth that they could not physically participate in delivery (removing the woman’s autonomy in the situation) or care for their baby post-delivery. Babies were born medicated or had to be delivered with aids such as forceps, risking injury to the baby. In some cases, while the women were still under anesthesia, further medical procedures, such as hysterectomies or tubal ligation, were performed without their awareness or consent.[14]

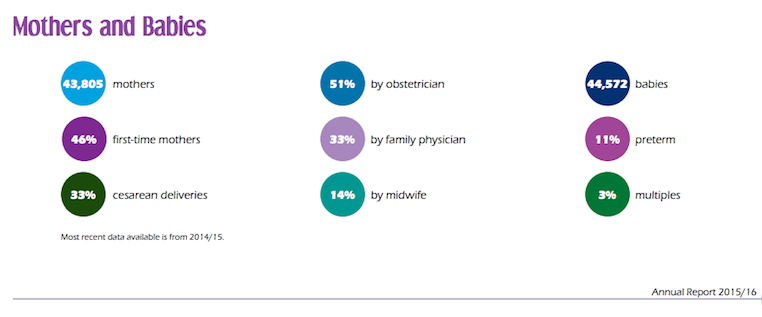

Today, the normal life events of pregnancy and childbirth remain largely within the scope of medical control. Throughout pregnancy, women are usually examined by physicians in clinical settings. Childbirth frequently occurs within a hospital, where women are generally attended by clinical health care providers and, even in non-emergency situations, may be offered or administered drugs to aid in the childbirthing process. Women may also have elective cesarean deliveries, further requiring medical intervention.[4]

Pregnancy and childbirth are areas where medicalization has resulted in more readily apparent positives. Infant and neonatal mortality and maternal rates continue to decrease.[15][16] That women in developed countries can choose to have an abortion, cesarean deliveries, pain relief, or to be supported by a doula or midwife during childbirth speaks to an increase in options and women reclaiming agency around the reproductive process.

However, home births and midwife attendance are still considered alternative practices. As of 2015, about 3% of births in BC were home births; 32.4% of births were attended by a family physician; 51.2% by obstetricians, and 14.1% by midwives (Perinatal Services BC, 2015)[17] [18]. We are socialized to think of childbirth as more of a medical process versus a biological event.

Other female reproductive processes or hormone-driven phases impacted by medicalization include: puberty, menstruation, pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS), birth control, sexuality, early motherhood, breastfeeding, and menopause.[11][4][12]

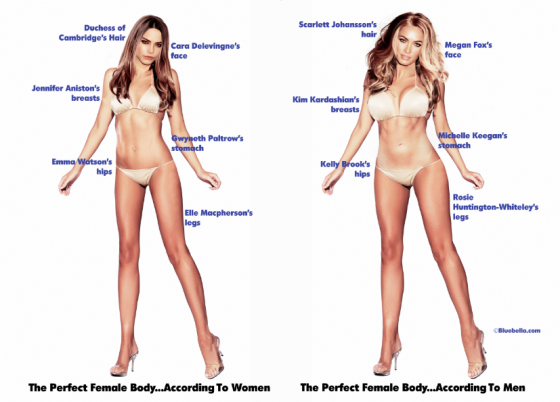

Humans Come In All Shapes and Sizes

There is naturally great variety in the human figure, and what is perceived as beautiful varies across cultures and time. Modern mainstream media continues to promote highly gendered, unrealistic, and narrow beauty ideals. Rather than celebrating diversity, there is an emphasis on white beauty and attaining specific proportions. At every stage in life, from adolescence, to post-pregnancy, to aging, women are bombarded with messaging regarding what their "best self" is and how to achieve this goal.

Looking at just one aspect of a women’s physique (breasts) demonstrates how medicalization is used to categorize variance in women’s bodies: There are medical terms for small breasts (micromastia or hypomastia), large breasts (macromastia or gigantomastia), and sagging breasts (breast ptosis). Treatment for these “conditions” involves medical or surgical interventions. Another trending procedure is the “Mommy Makeover”; this casts women’s post-pregnancy physique as a problematic condition that can be treated and transformed through surgery.[19]

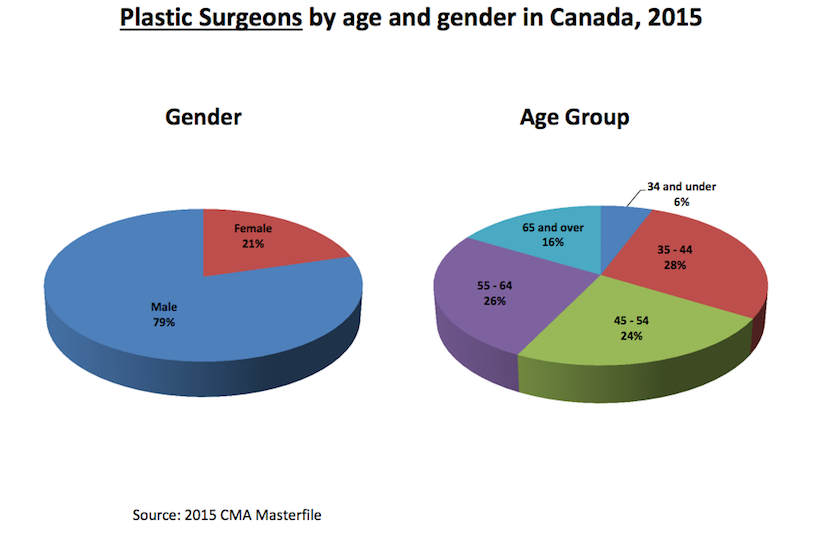

Plastic surgery is generally a male-dominated profession. In Canada, 79% of plastic surgeons are male (Canadian Medical Association, 2015).[20]

Medicalization continues to affect women’s agency and well-being today. As medical knowledge continues to expand, it is important for women to be aware of how medicalization can be a form of social control, and to look for opportunities in personal, professional, and policymaking spheres to resist its influence.

Related Information

Women in developing countries; women of low socioeconomic status, women of colour and/or other minority groups are often further disproportionately affected by medicalization.

- Women's Reproductive Autonomy: Medicalisation and Beyond

- Low-income Women's Experience of Medicalized Infertility

- Lady Science no.12: American and the Pill

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Conrad, P. (2008). The medicalization of society: On the transformation of human conditions into treatable disorders. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Waggoner, M. R. & Stults, C. D. (2010). Gender and medicalization: Sociologists for women in society fact sheet.

- ↑ Pizzini, F. (2000). The medicalization of women’s body. 4th European Feminist Research Conference.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Plechner, D. (2000). Women, medicine, and sociology: thoughts on the need for a critical feminist perspective. In J. J. Kronenfield (Ed.), Health, illness, and use of care: The impact of social factors (69–94). Emerald Group Publishers Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0275-4959(00)80023-X

- ↑ Frigon, S. (1995). A genealogy of women’s madness. In R. E. Dobash, R. R Dobash, & L. Noaks (Eds.), Gender and crime (20–8). Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- ↑ Purdy, L. (2001). Medicalization, medical necessity, and feminist medicine. Bioethics 15(3), 248–261.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M. G., & Fadda, B. (2012.) Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 110–119.

- ↑ Blumberg, J. (2007, October 23). A brief history of the Salem Witch Trials. Smithsonian.com

- ↑ Maines, R. P. (1999). The technology of orgasm: “Hysteria,” the vibrator, and women’s sexual satisfaction. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Life and Treatment at the London Asylum: The Historical Female. Retrieved from: https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/londonasylum/credits.html

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ussher, J. M. (2010). Are we medicalizing women’s misery? A critical review of women’s higher rates of reported depression. Feminism and Psychology 20(1), 9–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959353509350213

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Liebert, R. (2010). Feminist psychology, hormones and the raging politics of medicalization. Feminism and Psychology 20(2), 278–283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959353509360567

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Barlow, D. H., Durand, M. V., Steward, S. H., & Lalumiere, M. L. (2015.) Abnormal psychology (4th Cdn ed.). Nelson Education Ltd.

- ↑ The University of Minnesota: How Has Childbirth Changed in This Century? (2013). Retrieved from: http://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/explore-healing-practices/holistic-pregnancy-childbirth/how-has-childbirth-changed-century

- ↑ UN-IGME. (2015). Levels and trends in child mortality 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.childmortality.org/files_v20/download/IGME%20Report%202015_9_3%20LR%20Web.pdf

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2015). Maternal mortality fact sheet no. 348. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/

- ↑ Perinatal Services BC: Giving Birth in BC. (2015).

- ↑ Perinatal Services BC: Annual Report 2015/16. Retrieved from: http://www.perinatalservicesbc.ca/Documents/About/AnnualReport/PSBCAnnualReport2015_16.pdf

- ↑ Abate, M. A. (2010). “Plastic makes perfect”: My beautiful mommy, cosmetic surgery, and the medicalization of motherhood. Women’s Studies 39(7), 715–746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2010.505152

- ↑ Canadian Medical Association: Plastic Surgery Profile (2015). Retrieved from: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/Plastic-Surgery-e.pdf