MET:Promoting Success In E-Learning For The High School Student

Distance education has a long and important tradition in Canada, and continues to play a central role in educating our high school students. In British Columbia, there are over 900 grade 12 online courses currently being offered by various school districts and independent schools here in B.C. [1] . Moving beyond the paper-and-mail correspondence schools of the past, today distance education is more often delivered via the Internet, video conferencing systems, or other electronic modalities. Variously known as online education, distributed learning, e-Learning, or web-based instruction, today’s distance education offers significant opportunities for engaging students through the use of improved synchronous and asynchronous communication tools, multimedia, and inter-activities, but requires critical considerations in its design and delivery if it is to provide instruction that is comparable to more traditional classrooms. Furthermore, student attrition in online high school programs is often high. Planning a successful online high school program also requires having in place systems and policies that support student retention. Courses that merely post lecture notes, downloadable assignments, and make minimal or ineffective use of multimedia will do little to engage today’s students.

Is This Your Online Class?

Please watch the video below:

| Courses that merely post lecture notes, downloadable assignments, and make minimal or ineffective use of multimedia will do little to engage today’s students. How would you feel if you were a high school or a tuition-paying university student and this is what your online class was like?

Watching this, we understand that unless we were supremely motivated and independent students our chances of success would not be high. Yet it is likely that there are high school online classes that fit this mold. Particularly in many K-12 school divisions that do not have funding for online course development, online courses have the potential for being poor replacements for rich face-to-face classrooms. What are some of the critical considerations that need to be addressed when developing an online program or course for high school students? |

Essential Principles

The International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL), the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB), and the Sloan Consortium provide research-based guidelines and best practices for online K-12 education. Success in online learning depends on several key factors; future wiki postings may wish to fully explore each topic in greater depth:

- Student Characteristics

- Teacher Characteristics & Pedagogy

- Course Structure & Design

- Learner Supports

- Administration & Technical Issues

Student Characteristics

Online self-assessment surveys for potential online students such as OntarioLearn and LearnNowBC highlight the habits and skills that research has shown to be predictors of success for online learning[2]. Key characteristics may be broken down into the following general categories:

- Learner Attributes

- Time to actively participate in the class

- Stong time management, study skills & self-discipline

- Motivated

- Strong reading comprehension and writing skills

- Willing to ask questions

- Technology Skills - Competent users of technology

- Word processing

- File management skills

- Sending and receiving emails including file attachments

- Basic Internet skills including searches

- Able to install and remove software

- Access to Technology

- Regular access to computers at school and preferably at home and/or a library

- Reliable Internet access

While ideally all students taking online courses would possess all of these traits, this is not always the reality. Students commonly enroll in online courses not because it suites their particular learning style but because it provides necessary course options. This perfect set of traits described for online learners often reflect the adult learner more than adolescents who often require more structure and greater levels of interaction[3]. Thus additional supports need to be provided through instructional practices and course design in addition to other support services.

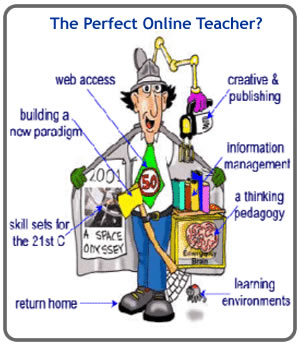

Teacher Characteristics & Pedagogy

|

Constructivist, learner-centered pedagogies are central to current theories of online learning [4], [5]. The main idea behind constructivist teaching is for students ot build their own knowledge. [6] Students should have an awareness of their own understanding and compare this understanding with what happens around them. Constructivist believe that "knowledge is not a transferable commodity and communication is not a conveyance" [7] Courses that promote student engagement through the use of activities that foster knowledge-building and facilitate interaction between individual students and between students and the content are now seen as essential attributes of online learning environments. These approaches mesh well with promoting favourable student attributes for success in an online environment, notably by encouraging active participation by students.

It is a myth that any qualified teacher is an effective online teacher [9]. Effective online teachers understand the special affordances provided and required by the online environment and have a sound understanding of effective online pedagogy. [10] Implicit in this understanding is a recognition of the unique features of online teaching:[11]

|

The SREB provides a comprehensive list of guidelines for quality online teaching:[12]. Broad areas of expertise are required in:

- Academic Preparation

. . . as required by any teacher.

- Content Knowledge, Skills and Temperatment for Instructional Technology

. . . such as possessing required technical skills, basic trouble-shooting abilities, and perhaps most importantly the "ability to effectively use and incorporate subject-specific and developmentall appropriate software".

- Online Teaching and Learning Methodology, Management, Knowledge, Skills and Delivery

. . . which is most central to providing a successful educational experience to online students. Standards for this particular guideline involve:

- Planning, desiging, and inocrporating strategies to encourage active learning, interaction, participation, and collaboration

- Providing egular feedback, prompt response, and clear expectations

- Modelling of legal, ethical, safe, and healthy uses of technology

- Responsivenes to students with special needs

- Competent in creating and implementing assessments in online learning environments that are valid and reliable

- Development and delivery of assessments including projects and assignments that assess required learning goals and measure student progress

- Effective use of assessment data to guide teaching practicies, and make adjustments and modifications to these practices when data suggest the need

- Providing frequent and effective strategies that enable both teacher and students to complete self- and pre-assessments

Course Structure & Design

Common guidelines for online courses are provided by the SREB[13], iNACOL [14], Wright (n.d.)[15] and others[16]. Key considerations include:

- Course Content

- Must meet all provincial standards for content

- Course material should be free of gender and cultural bias

- Content is accurate and current

- Course requirements should be clearly articulated

- Instructional Design

- Activities should engage students with active learning experiences

- Multiple learning paths should be available to provide for learner-centered instruction

- Opportunities to provide for interaction and communications between students and between instructor and students are essential

- A user-friendly design should be used to minimize student effort in learning how to manage the technology at the expense of mastering content

- Student aids such as time sheets and concrete deadlines with some flexibility can help students develop effective time management strategies

- Student Assessment

- Multiple strategies should be employed for student assessment, both to assess student readiness and progress

- Ample feedback should be provided to students regarding their progress

- Assessments should promote reflection by both students and the instructor in order to improve learning

- Technology

- A variety of technological tools should be employed

- Technology should meet all standards for accessibility for students with special needs

- Whenever possible the course and all materials should be platform-independent

- Course Evaluation & Management

- The course should be evaluated regularly for effectiveness

- Current research into student learning should guide course structure, design, and instruction

Course developers must be cognizant that it is not always the best and brightest students that will be taking the online course. Developing courses more towards the average and below average student is a more useful approach, with enrichment activities provided for above average students[17].

Learning Supports, Administration & Technical Issues

Beyond the virtual walls of successful online classrooms are additional supports for learners and teachers. For example:

- For Students

Student success in online courses is greatly enhanced by the presence of a local facilitator who assists in monitoring student progress, assisting students develop appropriate time management skills, and who can aid students in solving problems when they arise. This is particularly effective when local facilitators have been trained in learner-centered principles[18]. Other administrative supports for students may include locating and providing support materials such as textbooks and arranging for tutoring when needed. Local facilitators should encourage students to discuss any problems with their online teacher. These supports are often critical for the high school student who may be more likely to drop a course when they encounter difficulties.

- For Teachers

Professional development for teachers must be ongoing[19] and move beyond training in technological skills and address pedagogical issues as well. Topics may include helping teachers motivate students, enchancing student interactions particularly in the absence of visual cues, and developing Web 2.0 and 21st century skills[20]. There are also communities of professional teachers who support each other with course development and online course content. For example, B.C. Learning Network has 46 B.C. school districts working together to provide support to online teachers and allow collaboration of teacher. As well, for teachers who use Moodle as their LMS, MoodleDocs is another great place to find solutions to problems from gradebook to discussion forms.

- Technology

Technical considerations include the deployment and support of the technological infrastructure. Most online programs are supported by a learning management system (LMS) such as Blackboard or Moodle. Technical support must be readily available to both students and teachers to minimize down time and frustrations due to technological challenges. New technologies must be assessed and evaluated for their effectiveness. Bates and Poole's SECTION model[21] provides a framework for their selection. Each school district usually have a technology support team (or ServiceDesk). It is important for a high school online program to have at least one person who is available to offer tech support. This allows teachers to focus on interacting with the students, as well as on course development

Reasons for Taking an Online Course

Understanding why students take an online course helps the teacher to provide the necessary support to students to help them achieve their goal.

1. Course upgrades (to get a better mark)

These students have completed the course, and are just looking to get a better mark (mostly for post-secondary application purposes). Since post-secondary application is the reason for taking the course, the teacher should remind students to check with their post-secondary institutions to make sure they finish the course in time to meet the application deadline. A list of detailed due dates for coursework should also be provided.

2. The course does not fit in their school schedule

The teacher should have times available outside the 9 am - 3 pm school hours for these students to ask questions via email. It is also a good idea for the teacher to have online office hours outside the regular school hours for test-writing purposes and course support.

3. Students want to take an additional course outside of their course schedule

The teacher should have times available outside the 9 am - 3 pm school hours for these students to ask questions via email. It is also a good idea for the teacher to have online office hours outside the regular school hours for test-writing purposes and course support.

4. Students did not experience success with the course at their school, and want to try an alternative delivery method

These students often need more support, and some may have an Individual Education Plan which outlines the adaptations required in order for the student to be successful. In this case, it is important for the online teacher to work with the student's case manager to provide support.

Challenges in High School Online Education

1. Misconceptions about online courses

Students and parents often have misconceptions regarding online courses. Some students think that online courses are somehow "easier" than traditional face-to-face courses. Due to the fact that online teachers do not see students everyday, the course delivery structure and format can be quite different from face-to-face courses. For example, in a traditional face-to-face class, it is easier for a teacher to check students' homework everyday. However, in online courses, students often are only required to submit one big assignment at the end of a unit. This may give students the idea that online courses require 'less work'. Students and parents also may not know what are required in online courses, and they register simply because of the flexibility of online course. [22] Unfortunately, these students (and parents)will later find out that online courses require a lot of student participation and a very high level of self-regulation. [23] Flexibility does not mean students can progress at their own liking, as there are often due dates students need to meet in an online course. Students who do not have good time management skills and the willingness to take initiative when encounter problems often find less success in online courses. Interestingly, online instructors also think that online course preparation requires more time than traditional instruction. [24] Instructors who have not taught an online course before may be reluctant to enter the field because of the "fear of the unknown".

Possible Solutions: It is essential that the school of enrollment support and transition the learner to the unique challenges that accompany online learning. While many students find that online learning allows them to learn “anytime, place, path or pace” and they prefer this method over constant face to face instruction, many students struggle to schedule themselves accordingly and complete work.

There should be an ongoing communication between teacher, parents and student regarding the expectations and demands of online courses. These should also be stated clearly in the course outline. Swan (2001) suggested that interactions between the instructor and students significantly improved students' satisfaction and perception of online courses. [25]. School districts can also administer a self-assessment questionnaire to help students and parents aware of the requirements needed for an online course. For example, Minnesota State Colleges and Universities provide a questionnaire for students to assess if they are suitable for an online course Minnesota Online Questionnaire The self-assessment helps students to think about their own technological readiness, competency in online communication and Time management skills. [26] Administrators should encourage collaboration between online teachers and students' high schools. This collaboration helps teachers in local high schools to learn about online courses, and also the possibility of providing facilitators in schools to assist students' online courses.[27] These facilitators help to supervise online tests, as well as providing support to students in helping them to access their course, and provide feedback to the online course teacher. In additional, administrators should provide new online course teachers with different opportunities for professional development to ease the anxiety of entering a new field.

2. Academic Dishonesty

In Reimer's article, he stated that 38% of undergraduate students confessed that they had engaged in Internet plagiarism [28] Even though this study was done at the post-secondary level, it is undeniable that Internet plagiarism is increasing. When students submit assignments online, it is difficult to prove that they are the ones who have actually done the assignment. When students are on the computer, it is very easy for them to access different websites and software, and use them in an inappropriate way. In my personal experience, some students engage in plagiarism without knowing what they've done is actually an act academic dishonesty (ex. comparing answers on a math assignment to the same assignment that has already been marked by the teacher). As a result, it is very important to educate students about the importance of academic integrity, especially at the high school level. This will help them to be successful in online courses, and also help them for post-secondary studies. Another motivation for cheating is also the desire to do well. Students want to get a good mark in their online course - especially when they are taking the course to upgrade their mark.

Possible solutions: Jones discovered that many students had a hard time identifying what was and was not plagiarism. [29] Therefore, at the beginning of an online course, the teacher should provide a tutorial or a document that teaches students what are and are not plagiarism. A good example is the Academic Integrity Tutorial provided by York University. Another good strategy is to let students know that their access to the course materials can always be tracked by the teacher. [30]. Therefore, if they haven't spent much time on a module, but has produced assignments that do not match the amount of time spent, further investigation will result. It is also a good practice to check students' ID before they write an exam. This validates their identity and ensures that whoever doing the test is the student him/herself. The teacher should also provide adequate feedback and opportunities for students to improve their mark to ease students' anxiety to o well. This will help to reduce students' likelihood of cheating because they want a better mark.

3. Promoting Meaningful Student-Student Interactions '

It's much easier to facilitate peer interactions in a synchronous online course. However, many high school online courses are asynchronous, and students can register throughout the year and progress at a different pace. Kerr (2009) pointed out in her article that "asynchronous learning communities become much more challenging when working with students who enroll at different times through the year". [31] While online interactions and discussion forums help students to build a stronger learning community, Hammond (2008) found that unless online discussion posts are required, students often don't post on a regular basis.[32] As an online teacher, the author of this post has found that when discussion forum posts a required component of the course, there is a lot of student participation. However, if it is not a requirement of the course, many students are reluctant to post questions or respond to other students' posts. Furthermore, students tend to email the teacher directly when they have questions (as opposed to asking each other for ideas). However, while many teachers believe in the effectiveness of online participation, Davies and Graff found that increased participation in online discussions did not result in better grades [33] Furthermore, Tallent-Runnets (2008) also found that asynchronous communication in online courses helped students to engage in in-depth discussions, but these discussions were not more than face-to-face classes. [34] As a result, it is important for a teacher to design online discussions strategically to promote critical thinking. Instead of focusing on improving students' grades, the focus should be allowing students to make connections between concepts and also make progressions in their thinking processes.

Possible Solutions: Kerr (2008) suggested providing training to educators in the importance of building a community; choosing meaningful activities and discussion topics, use effective technology; encourage collaboration amongst students, and use of peer mentors. [35] In an asynchronous online course, the teacher could pair a new student with a students who started the course at an earlier date. This student would be the mentor to the new student, and could help the new student with how to access materials, and on content questions. The teacher could also use synchronous discussions (ex. Blackboard Collaborate) to provide real-time support to students. This online environment allows students to ask and respond to each other's questions, and creates a virtual classroom. It also helps to solidify the presence of the teacher, as well as the other classmates. Interestingly, Anderson also suggested the teacher to find different ways to express emotions and passion for the course. [36] Online communication can be too text-based, and this takes out the emotional and personal aspects of face-to-face interactions. This adds the 'human touch' to online communication and again would strengthen the presence of the teacher.

Conclusions

As we make advancements in technological aspect of online education, we should never forget that the goal of education is to empower students. Creating a successful online learning experience for high school students requires much more than simply posting content in a LMS for students to retrieve and complete. Adolescents in particular require a more structured and supportive environment than adult learners. Organizations such as the [2] and iNACOL provide useful research-based guidelines on creating and providing learner-centered environments for online K-12 students. Online teachers should also be engaged in continuous professional development to learn more about their LMS, as well as new technological tools that facilitate students' learning. Teachers should also be a part of a larger professional community to provide support to each other. Online courses are not necessarily better or worse then traditional face-to-face courses. As teachers learn more about online education, and with the current researches, it is very hopefully that high school online education will continue to improve to provide meaningful education to students.

Canadian K-12 Online Learning Links

Notes

- ↑ LearnNowBC. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.learnnowbc.ca/default.aspx

- ↑ Mandernach, B.J., Donnelli, E. & Dailey-Hebert, A. (2006). Learner attribute research juxtaposed with online instructor experience: Predictors of success in the accelerated, online classroom. The Journal of Educators Online 3(2): 1-17.

- ↑ Barbour, M. K. (2007). Principles of effective web-based content for secondary school students: Teacher and developer perceptions. Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 93-114. Retrieved from http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/30

- ↑ Anderson, T. (2008). “Towards and Theory of Online Learning.” In Anderson, T. & Elloumi, F. Theory and Practice of Online Learning. Athabasca University.

- ↑ Conrad, D. (2007). The plain hard work of teaching online: Strategies for instructors. In M. Bullen & D.P. Janes (Eds.), Making the transition to online learning (pp. 191-207).Hershey: Information Science Publishing.

- ↑ Von Glasersfeld, E. (2003). Ernet von Glasersfeld cybernetics, wisdom, and radical constructivism [Video file]. Retried from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YozoZxblQx8

- ↑ Von Glasersfeld, E. (2008). Learning as a constructive activity. AntiMatters, 2(3), 33-49. Available online: http://anti-matters.org/articles/73/public/73-66-1-PB.pdf

- ↑ Barbour, M. K. (2007). Principles of effective web-based content for secondary school students: Teacher and developer perceptions. Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 93-114. Retrieved from [1]

- ↑ Davis, Niki and Rose, Ray. (2007). Professional Development for Virtual Schooling and Online Learning. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Pages 17-19. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/docs/NACOL_PDforVSandOlnLrng.pdf

- ↑ Wicks, M. (2010). A national primer on K-12 online learning: Version 2. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/bookstore/detail.php?id=22

- ↑ Southern Regional Education Board. (2003). Essential principles of high-quality online teaching: Guidelines for evaluating K-12 online teachers. Publication #03T01. Available online: http://info.sreb.org/programs/EdTech/pubs/PDF/Essential_Principles.pdf

- ↑ Southern Regional Education Board. (2006). Standards for quality online teaching. Publication #: 06T02 Available online: http://publications.sreb.org/2006/06T02_Standards_Online_Teaching.pdf

- ↑ Southern Regional Education Board. (2006). Standards for quality online courses. Publication #: 06T05. Available online: http://publications.sreb.org/2006/06T05_Standards_quality_online_courses.pdf

- ↑ Wicks, M. (2010). A national primer on K-12 online learning: Version 2. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/bookstore/detail.php?id=22

- ↑ Wright, C.R. (n.d.) Criteria for evaluating the quality of online courses. Available online: http://elearning.typepad.com/thelearnedman/ID/evaluatingcourses

- ↑ Cavanaugh, C. And Clark, T. (2007). The landscape of K-12 online learning. In C. Cavanaugh and R. Blomeyer (Eds.). What works in K-12 online learning (pp. 5-20). Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

- ↑ Barbour, M. K. (2007). Principles of effective web-based content for secondary school students: Teacher and developer perceptions. Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 93-114. Available online: http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/30

- ↑ Hannum, W.W., Irvin, M.J., Lei, P., and Farmer, T.W. 2008). Effectiveness of using learner-centered principles on student retention in distance education courses in rural schools. Distance Education 29(3):211-229.

- ↑ Cavanaugh, C. And Clark, T. (2007). The landscape of K-12 online learning. In C. Cavanaugh and R. Blomeyer (Eds.). What works in K-12 online learning (pp. 5-20). Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

- ↑ Watson, John & Gemin, Butch. (2009). iNACOL Promising Practices In Online Learning: Management and Operations of Online Programs: Ensuring Quality and Accountability. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/promisingpractices/iNACOL_PP_MgmntOp_042309.pdf

- ↑ Bates, A.W., and Poole, G. (2003). Effective teaching with technology in higher education: Foundations for success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. 79 - 80.

- ↑ Kim, P., Kim , F. H., & Karimi, A. (2012). Public online charter school students: Choices, perceptions, and traits. American Education Research Journal, 49(3), p.522.

- ↑ Kim, P., Kim , F. H., & Karimi, A. (2012). Public online charter school students: Choices, perceptions, and traits. American Education Research Journal, 49(3), p.522.

- ↑ Roby, T., Ashe, S., Singh, N., & Clark, C. (2013). Shaping the online experience: How administrators can influence student and instructor perceptions through policy and practice. Internet and Higher Education, 17, p.30

- ↑ Roby, T., Ashe, S., Singh, N., & Clark, C. (2013). Shaping the online experience: How administrators can influence student and instructor perceptions through policy and practice. Internet and Higher Education, 17, p.30

- ↑ Hunte, S. (2012). First time online learners' perceptions of support services provided. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education - TOJDE, 13(2), p.190

- ↑ de la Varre, C., Keane, J., & Irvin, M. J. (2010). Enhancing online distance education in small rural U.S. schools: A hybrid, learner-centered model. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 15(4), p.35

- ↑ Jones, D. (n.d.). Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating?. Business Communication Quarterly, 74(2), p.141. doi: DOI: 10.1177/1080569911404059

- ↑ Jones, D. (n.d.). Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating?. Business Communication Quarterly, 74(2), p.147. doi: DOI: 10.1177/1080569911404059

- ↑ Kleinman, S. (2005). Strategies for Encouraging Active Learning, Interaction, and Academic Integrity in Online Courses. Communication Teacher, 19(1), p.15

- ↑ Kerr, C. (2009). Creating Asynchronous Online Learning Communities. Ontario Action Researcher, 10(2), p.2

- ↑ Woo, Y., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Interaction in Asynchronous Web-Based Learning Environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), p.182

- ↑ Woo, Y., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Interaction in Asynchronous Web-Based Learning Environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), p.180

- ↑ Woo, Y., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Interaction in Asynchronous Web-Based Learning Environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), p.180

- ↑ Kerr, C. (2009). Creating Asynchronous Online Learning Communities. Ontario Action Researcher, 10(2), p.2

- ↑ Andresen, M. A. (2009). Asynchronous Discussion Forums: Success Factors, Outcomes, Assessments, and Limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 12(1), p.250

References

Andresen, M. A. (2009). Asynchronous Discussion Forums: Success Factors, Outcomes, Assessments, and Limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 12(1), 249-257.

Anderson, T. (2008). “Towards and Theory of Online Learning.” In Anderson, T. & Elloumi, F. Theory and Practice of Online Learning. Athabasca University.

Barbour, M. K. (2010). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. iNacol. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/docs/iNACOL_CanadaStudy10-finalweb.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2007). Principles of effective web-based content for secondary school students: Teacher and developer perceptions. Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 93-114. Retrieved from http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/30

Barbour, M.K. (2009). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/docs/iNACOL_CanadaStudy10-finalweb.pdf

Bates, A.W., and Poole, G. (2003). Effective teaching with technology in higher education: Foundations for success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. 79 - 80.

B.C. Learning Network (2013). Retrieved from http://bclearningnetwork.com/m2/.

Cavanaugh, C. And Clark, T. (2007). The landscape of K-12 online learning. In C. Cavanaugh and R. Blomeyer (Eds.). What works in K-12 online learning (pp. 5-20). Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

Conrad, D. (2007). The plain hard work of teaching online: Strategies for instructors. In M. Bullen & D.P. Janes (Eds.), Making the transition to online learning (pp. 191-207).Hershey: Information Science Publishing.

Davis, Niki and Rose, Ray. (2007). Professional Development for Virtual Schooling and Online Learning. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Pages 17-19. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/docs/NACOL_PDforVSandOlnLrng.pdf

de la Varre, C., Keane, J., & Irvin, M. J. (2010). Enhancing online distance education in small rural U.S. schools: A hybrid, learner-centered model. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 15(4), 35-46.

Farrell, B., Lawson, P., and Smith, R. (2010). A framework for online learning. Created for ETEC 532, University of British Columbia.

Hannum, W.W., Irvin, M.J., Lei, P., and Farmer, T.W. 2008). Effectiveness of using learner-centered principles on student retention in distance education courses in rural schools. Distance Education 29(3):211-229.

Hunte, S. (2012). First time online learners' perceptions of support services provided. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education - TOJDE, 13(2), 180-197.

Jones, D. (n.d.). Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating?. Business Communication Quarterly, 74(2), 141-150. doi: DOI: 10.1177/1080569911404059.

Kerr, C. (2009). Creating Asynchronous Online Learning Communities. Ontario Action Researcher, 10(2), 1-20.

Kim, P., Kim , F. H., & Karimi, A. (2012). Public online charter school students: Choices, perceptions, and traits. American Education Research Journal, 49(3), 521-545.

Kleinman, S. (2005). Strategies for Encouraging Active Learning, Interaction, and Academic Integrity in Online Courses. Communication Teacher, 19(1), 13-18.

LearnNowBC. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.learnnowbc.ca/default.aspx

Mandernach, B.J., Donnelli, E. & Dailey-Hebert, A. (2006). Learner attribute research juxtaposed with online instructor experience: Predictors of success in the accelerated, online classroom. The Journal of Educators Online 3(2): 1-17.

mokmcdaniel. Online student experience. Retrieved June 1, 2011, from: [3].

Roby, T., Ashe, S., Singh, N., & Clark, C. (2013). Shaping the online experience: How administrators can influence student and instructor perceptions through policy and practice. Internet and Higher Education, 17, 29-37.

Southern Regional Education Board. (2003). Essential principles of high-quality online teaching: Guidelines for evaluating K-12 online teachers. Publication #03T01. Available online: http://info.sreb.org/programs/EdTech/pubs/PDF/Essential_Principles.pdf

Southern Regional Education Board. (2006a). Standards for quality online teaching. Publication #: 06T02 Available online: http://publications.sreb.org/2006/06T02_Standards_Online_Teaching.pdf

Southern Regional Education Board. (2006b). Standards for quality online courses. Publication #: 06T05. Available online: http://publications.sreb.org/2006/06T05_Standards_quality_online_courses.pdf

[Untitled graphic of online student] Retrieved July 1, 2011, from: http://www.prweb.com/releases/2010/08/prweb3806784.htm

The Perfect Online Teacher. [graphic] Retrieved July 1, 2011, from: http://www.theenglishteacheronline.com/the-perfect-online-teacher/

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2003). Ernet von Glasersfeld cybernetics, wisdom, and radical constructivism [Video file]. Retried from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YozoZxblQx8

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2008). Learning as a constructive activity. AntiMatters, 2(3), 33-49. Available online: http://anti-matters.org/articles/73/public/73-66-1-PB.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Watson, John & Gemin, Butch. (2009). iNACOL Promising Practices In Online Learning: Management and Operations of Online Programs: Ensuring Quality and Accountability. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/promisingpractices/iNACOL_PP_MgmntOp_042309.pdf

Wicks, M. (2010). A national primer on K-12 online learning: Version 2. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Available online: http://www.inacol.org/research/bookstore/detail.php?id=22

Woo, Y., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Interaction in Asynchronous Web-Based Learning Environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), 179-194.

Wright, C. R. (n.d.) Criteria for evaluating the quality of online courses. Edmonton. Available online: http://elearning.typepad.com/thelearnedman/ID/evaluatingcourses.pdf