MET:Forgetting

This page was originally authored by Yu Tian (2007).

This page has been revised by Jim Tattrie (2008) and Dieder Bylsma (2008).

Page revised by Erin Howard (2018).

| Without memory we cannot learn. But if we remembered everything then who would we be? This article aims to examine the processes involved in the inability to retrieve information stored in one’s mind. At the end of the article we will also examine briefly the benefits which exist to being able to forget. This will not be an article about memory manipulation by foreign agents or movies such as The Manchurian Candidate (2002 or 1962 versions) or the recent film Eternal Sunshine! Hopefully this article will not be easily forgotten! |

Forgetting

Forgetting is the name given to two similar phenomena; forgetting is the loss of information from memory; forgetting also can refer to the inability to access information previously stored in memory. Information processing theories focus on attention, perception, encoding, storage and retrieval of knowledge. When retrieving knowledge from memory, people often forget a lot despite our best intentions.. Four types of forgetting are presented from an information processing perspective and some additional information is given about what would happen if forgetting were not an issue.

Theories of Forgetting

Video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dk11cuQPHKc Asuncion Perez, added on February 9, 2015

Interference theory

- According to the interference theory of forgetting, forgetting results from competing associations that lower the probability of the correct association being recalled; that is, other material becomes associated with the original stimulus (Schunk 2004). This means that current information is lost because it is mixed up with previously learned and similar information. Forgetting occurs in the retrieval process rather than in the actual memory itself.

- Two types of interference are identified.

- Retroactive interference refers when previously learned information is lost because it is mixed up with new and somewhat similar information.

- Proactive interference occurs when new information is lost because it is mixed up with previously learned, similar information.

Fading

- Fading occurs when we can no longer recall information from our memory because of disuse. In short-term memory – also known as working memory– fading can occur very rapidly - in some cases after a few seconds — i.e. short-term auditory memory. When information fades from working memory, it disappears because the short-term space was needed for other incoming information. We can prevent this type of fading by continuing to focus attention on the information, by constantly rehearsing it, or by transferring it to long-term memory. It is of course possible to train one's short-term memory through a variety of techniques dependent upon the situation or goal state — otherwise we would not have professional interpreters capable of simultaneous translation.

Distortion

- Distortion refers to the misrepresentation of information that occurs when an imperfect image is recalled from long-term long term memory. It is not really a separate type of forgetting, but rather a combination of the previous three types - fading, retroactive and proactive interference.

Suppression

- Suppression is a term derived from the Freudian psychotherapy term repression which refers to the subconscious urge from within our personalities to obliterate unpleasant or threatening information from our memories.

Application in teaching and learning

According to different theories of forgetting, different strategies can deal with these obstacles in teaching and learning.

Sensory Register

- The information may never have reached the sensory register.

- Strategies

- Present the information clearly.

- Be sure that the learner perceives the information correctly.

- Be aware that what is perceived clearly by one person may not be perceived clearly by others.

- Be aware that the fact that the learner has perceived something clearly does not mean that the learner has perceived the accurate information clearly.

Incorrect register to memory transfer

- The information may not have been transferred correctly from the sensory register to working memory

- Strategies

- Help the learner actively attend to the information.

- Ask questions to ascertain that attention is correctly focused.

- Make sure attention is focused on the relevant information rather than peripheral information.

- If the learner has an attention deficit, deal with it.

Information retention difficulty

- The learner may have been unable to retain information accurately long enough to work with it.===

- Strategies

- Encourage repeated practice to keep information active in the working memory.

- Provide supplements to the working memory (such as written materials or diagrams to which the learner can easily refer).

- Encourage chunking, so that the learner can effectively focus on a wider span of information.

- Help the learner activate prior relevant knowledge to encourage chunking. (This will also facilitate transfer to and from long-term memory.)

- Promote over-learning of basic skills (those that will be used repeatedly), so that concentrating on these doesn't occupy valuable space in the working memory.

Incorrect transfer from working to long-term storage

- The learner may not have transferred the information correctly from working memory to long-term storage.

- Strategies

- Encourage active interaction with the information, so that the learner will make connections with existing knowledge.

- Help the learner to focus attention on these connections with existing knowledge.

- Encourage working with the information in more than a single context (so that more connections will be made.)

- Help the learner activate prior relevant knowledge to encourage chunking. (This will also facilitate chunking and will maximize the use of working memory.)

Difficulty retrieving long-term memory

- The learner may not have been able to bring the information back from long-term memory to working memory for active use on a later occasion.

- Strategies

- Practice in order to minimize fading. Practice works best if it is intermittent. Practice can consist of either reviewing the information or using that information as part of new learning activities.

- Focus attention actively while transferring information to long-term memory.

The need to forget

Societal implications of a permanent memory

- In addition to the metacognitive features of building and sustaining memories, there is also the reality that sometimes the ability to forget is an essential part of our lives. With the possibility of having a full audio-visual recording of our entire lives no longer effectively science fiction, the question becomes when do we need to forget? Jessica Winter in the Boston Globe “ writes an opinion piece about what it is to have a ‘perfect memory’ — be it the curse of Jorge Luis Borges's character “Funes” in “ Funes the Memorious ” or with the digital alternative now no longer completely science-fiction.

Personal benefits to forgetting

- Recent research has shown that there are also benefits to the ability to forget things. In Kuhl ’s 2007 study using functional MRI scanning with a variety of subjects, he showed that the benefits of forgetting include effectively the ability to 'prune' unnecessary information and have a more efficient neurological processing. Thus while forgetting and overcoming it is important as per the above sections, it also does have the benefit of making our memories more efficient for more important information to be encoded.

Stop Motion Video: Forgetting

- https://youtu.be/OhcGwdB5Hk8 added by Erin Howard, January 21, 2018.

References

- Note some links require UBC Campus Wide Login

- Abel, M., & Bäuml, K. (2013). Sleep can reduce proactive interference. Memory, 22(4), 332-339. doi 10.1080/09658211.2013.785570

- Anon. Referee [Online image]. Retrieved February 7, 2015 from Retrieved from http://www.theindychannel.com/news/hockey-101-referee-penalty-signals

- Anon.Daniel Schacter [Online image]. Retrieved February 7, 2015 from http:/gade.psy.ku.dk2014autobiographical_www/8414%20Dan%20Schacter.jpg

- Anon. 7 Sins of Memory[Online image]. Retrieved February 7, 2015 from

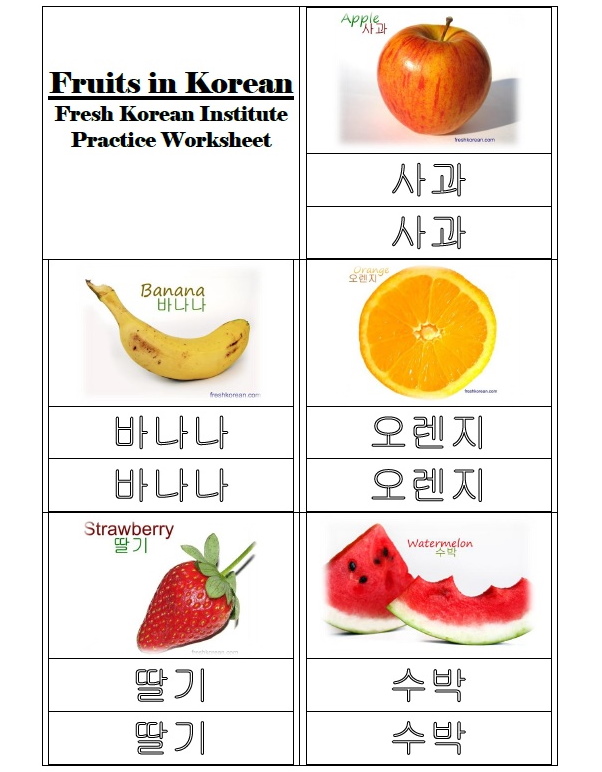

- Anon. Korean vocabulary[Online image]. Retrieved February 7, 2015 from

- Berry, J. A., Cervantes-Sandoval, I., Nicholas, E. P., & Davis, R. L. (2012). Dopamine Is Required for Learning and Forgetting in Drosophila. Neuron, 74(3), 530–542. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.007

- Borges, Jorge Luis Funes the Memorious — UBC library holdings

- Educ320 (Artist). (2016). Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Curve [Digital Image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Website: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ebbinghaus%E2%80%99s_Forgetting_Curve_(Figure_1).jpg

- Hadziselimovic, N., Vukojevic, V., Peter, F., Milnik, A., Fastenrath, M., Fenyves, B. G., ... & Papassotiropoulos, A. (2014). Forgetting is regulated via Musashi-mediated translational control of the Arp2/3 complex. Cell, 156(6), 1153-1166.

- Human-memory.net,. (2015). Short-Term Memory and Working Memory - Types of Memory - The Human Memory. Retrieved 9 February 2015, from http://www.human-memory.net/types_short.html

- Icez. (Artist). (2007) Forgetting Curve [Digital image]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons Website: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ForgettingCurve.svg

- Kraft, R. (2017, June 23). Why we forget. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/defining-memories/201706/why-we-forget

- Kuhl, Brice A, Dudukovic, Nicole M Kan, Itamar, Wagner, Anthony D. (2007). “Decreased demands on cognitive control reveal the neural processing benefits of forgetting” Nature Neuroscience 10, 908-914 . review in Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8, 495 (July 2007). {Original source article can be found here}

- Learn-english-today.com,. (2015). English idioms relating to memory or remembering.. Retrieved 9 February 2015, from http://www.learn-english-today.com/idioms/idiom-categories/memory/memory.html

- McLeod, S. (2015). Forgetting | Simply Psychology. Simplypsychology.org. Retrieved 9 February 2015, from http://www.simplypsychology.org/forgetting.html

- Memory-Improvement-Tips.com,. (2015). Forgetfulness - Tips for the Absentminded. Retrieved 9 February 2015, from http://www.memory-improvement-tips.com/forgetfulness.html

- Ohara, Kieron Shadbolt, Nigel Sleeman, Derek (2000) “ Psychological Literature on Forgetting v.3 18.12.00 ” Open University UK

- The Peak Performance Center. (n.d.) Forgetting. Retrieved from http://thepeakperformancecenter.com/educational-learning/learning/memory/forgetting/

- Psychlopedia.wikispaces.com,. (2015). Psychlopedia - proactive interference. Retrieved 9 February 2015, from http://psychlopedia.wikispaces.com/proactive+interference

- Schacter, D. (2003). How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. New York: Souvenir Press.

- Schunk, D. H. (2004). Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

- The Upside of Forgetting [YouTube]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5zH4N3ohR0

- Vockell, Edward. (2003) Educational Psychology: A Practical Approach. Chapter 6

- Winter, Jessica (2007). “ The Advantages of Amnesia ” in The Boston Globe

- Music: http://www.purple-planet.com

- Stock Images: https://pixabay.com/