MET:Edutainment

This page was originally authored by Sherman Chan (2007).

It has since been revised by: Raphael Barrett (2007), Mark Kampschuur (2007), Frank Chan (2008), Jagpal Uppal (2008), Jen Gilpin (2009), Irene Iwasaki (2011), Jennifer Schubert (2012), Lauren MacDonald (2015), Rebecca Skucas (2015), Scott Meech (2010) and Jamie Ashton (2018)

Stop Motion Artifact - Benefits of Edutainment -Lauren MacDonald

What is Edutainment?

Merriam-Webster defines edutainment as "entertainment (as by games, films, or shows) that is designed to be educational." The term was originally used in 1973 and defined by pioneers in the field as entertainment with an educational twist (Jasinski, 2004). The medium of edutainment is created with the intention to amuse or engage the viewer/participant while simultaneously imparting knowledge.Some forms of edutainment are originally created for entertainment value, but also deemed to be useful as teaching material in an educational setting. Other forms of edutainment are created specifically for educational purposes.

Advancements in technology have promoted the evolution of edutainment. As the world draws closer through digital communication, edutainment continues to spread globally. Websites, such as YouTube, allow for the posting and sharing of digital content internationally. Although the goal of uploading and sharing edutainment materials may be primarily for educational purposes, copyright laws must be considered and abided by before doing so.

The premise of Edutainment is to educate while being entertained. Sometimes the educational lesson within the medium is hidden; consequently, students are often learning without realizing it. Proponents of Edutainment argue that it provides a relevant and tangible learning experience for children, appealing to the need to address and encourage interest. This follows a constructivist view of learning whereby the learner constructs their own meaning as they learn. Critics argue that Edutainment provides a watered-down form of education where the medium becomes more important than the message.

Examples of Edutainment

Edutainment is created primarily for the purpose of entertaining its audience, but also serves to include educational information or involve an educational theme in a particular subject area(s). The following entertainment mediums may be used for educational purposes if the content is deemed appropriate by educators:

- Art (paintings, photographs, sculpture…especially that displayed in an exhibit or gallery for public viewing)

- Animation, comics, cartoons (such as political cartoons)

- Drama (skits, plays, puppetry in the performing arts or classic literature)

- Exhibits and museums (science centres, socio-political, anthropological history, ancient civilizations)

- Games such as manufactured board games which simulate life situations and problems to be solved

- Radio broadcasts and programs (music, interviews, talk shows)

- Commercials and advertisements (media and business studies)

- TV programs (discovery channel, history channel, PBS, criminal dramas)

- Films/movies

- News footage

- Documentaries

- Literary publications (newspapers, magazines, books and picture books)

- Live performances that have an element of spectacle (comedy, magic, athletics)

- Music (live or recorded)

- Video games

- Computer software

- Online websites

- Digital simulations and virtual worlds

- Audiovisuals, multimedia that has been recorded, published or displayed in a public forum

Incorporating any form of entertainment media or multi-media into an educational setting may be considered edutainment.

Edutainment Materials

Edutainment supplies may not be used as part of the regular school curriculum as they are easily assessed to be more for play or amusement than for study. They may also require much more funding than traditional learning supplies. Some examples of edutainment teaching materials:

- LeapFrog: a series of educational toys, including the LeapPad and Leapster, which allow preschool and primary grade children to listen, speak (record), read and write interactively with visually attractive electronic materials.

- VTech: a company which creates gaming platforms, including the V.Smile console.

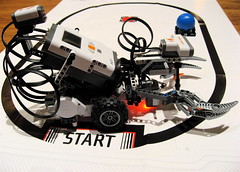

- Lego Mindstorms: a hands-on kit that allows learners to build electronic robots.

" "

"

Lego Mindstorms: Do-it-yourself robot kit

Pre-digital Edutainment

Although the term was coined in the early 1970’s, edutainment has arguably always existed in forms of:

- Moral teachings, parables such as in religious texts

- Teacher’s and elder’s engaging stories and jokes, prepared or whimsical

- Dramatic or comedic performance/expression which may include music and dance

- Stories, oral or written, depicting real or imagined events, that invite the reader to become emotionally involved or encourage personal reflection

These are example of early edutainment because they aimed to entertain while teaching, educating or inspiring. With the rise of manufacturing and technology, edutainment took on a more material and product-centred form.

Edutainment and Television

Since the introduction of television, there have been children's programs that aim to educate and entertain. In terms of globalization of media, one particular program, Sesame Street, educates and entertains children in over 120 countries and 20 languages worldwide. The premise behind educational television is that it's main goal is two-fold - to entertain and educate. The educational value of the programs are embedded and may not always be readily apparent. This form of learning is especially effective on children who have difficulty focusing on regular forms of learning.

Origins of Educational Children's Programming

In 1964, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “War on Poverty” in the annual State of the Union Address and in 1965 launched the Head Start program, an eight week summer enrichment program aimed at providing children from low income families with the academic and social tools to be ready to start Kindergarten. One of the most widely accepted research efforts of the era was that of Benjamin Bloom (1964) of the University of Chicago. Bloom’s research determined that “more than one half of a child’s lifetime intellectual capacity is formed by 5 years of age” (Bloom, 1964). Research efforts conducted in the mid-1960s by Carl Bereiter and Martin Deutch discovered that children from low income, minority households consistently tested substantially lower than those children raised in middle income, Caucasian families (Bereiter & Engelman, 1966; Deutch, 1965). Not only did the studies result in evidence of a lack in school readiness, but also proved that the effects of poverty on education were long-standing. Students were found to have far-reaching educational deficits tracked well into their school-age years.

In 1968, according to the A.C. Nielsen Company, a company historically responsible for analyzing statistics regarding American media usage, 97% of all American households owned a television set (A.C. Nielsen Company, 1967). Television was viewed as a highly accessible and viable way to enter diverse households in an effort to provide supplemental education to everyone, but most importantly, those on the lower end of the socio-economic scale. As part of the “War on Poverty,” the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) was created in March of 1968 with the primary focus of creating entertaining programs which would stimulate the educational progress of very young children before they reached school age. Sesame Street, a fast-paced magazine format show made up of 40 individual segments within an hour long program, filled with an entertaining cast of humans and puppets teaching general number concepts, alphabet and phonics skills, social etiquette and general life lessons through flashy cartoons, catchy songs and humorous skits, was born.

Until Sesame Street, most children’s programming was found to be in one of three formats: cartoon, storybook or proscenium (Palmer, 2001). Cartoon favorites of the day included Hannah-Barbara productions such as The Flintstones, The Jetsons, and Tom & Jerry. Storybook television consisted of literal camera shots of a book cover and subsequent illustrated, and narrated, pages. Proscenium television gave viewers a glimpse inside of an environment, typically populated with offbeat characters and often other children, where viewers were often addressed “through” their television, in an effort to create a sense of audience participation. One example of this would be the popular children’s program Romper Room in which the hostess, often ex-schoolteachers, would look into a make believe magic mirror and list popular names at the end of episodes in an effort to address children personally. “I see Scotty, Kimmy, Jenny and Jason.” Most of these proscenium programs were filmed and televised locally.

Sesame Street would be televised every weekday by way of Public Broadcasting. PBS, the first national public television network, was created in 1969, just in time for the very first broadcast of Sesame Street. PBS would combine 300 independent public television stations located throughout the United States into one single coverage area which reached approximately 67% of all homes. In 1969, there were 12 million 3 to 5 year old children ready to be reached by a new medium in television programming (Palmer, 2001). This meant that the potential was there to reach approximately 8 million viewers in its inauguration, which also proved to be cost effective.

Edward L. Palmer refers to the first season of Sesame Street as “the world’s biggest $8 million experiment in children’s television” (Palmer, 2001). The U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare supplied $4 million dollars, whilst the other $4 million was provided through corporate sponsors such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Ford Foundation. When working from money obtained through government program grants, as well as independent corporate sponsors, it is imperative to validate expenditures, especially if the work is to be reconsidered and relaunched successively.

Research Supporting Educational Television Programming

One key element to the success of Sesame Street, was the first documented usage of an in-house research and development team. Up until this point, children’s programming was typically envisioned, scripted and directed by a sole entity. Due to the educational mandates and accountability of being part of a governmental program launch, it was essential that the basis of entertainment be firmly cemented in curriculum. Using formative research to not only evaluate measurable learning goals but to plan each segment with corresponding measurable behavioral and learning outcomes was unprecedented and served as validation to the aims of the Children's Television Workshop.

Research conducted by Bogatz and Ball in the early 1970s served to show potential long-term benefits to viewership, particular to Sesame Street. Results of initial testing showed that amongst viewers aged 3 to 5, those who watched the show more regularly showed significant development in alphabetical & numerical conventions, indication of body parts, classification, sorting, recognition of shapes and relational language. Viewers of the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) showed greater improvement over their middle-SES peers for the first time. The effects of viewership transcended age, gender, first language (English vs. Spanish) and location (Bogatz and Ball, 1970). One year later, Bogatz and Ball had the same children’s teachers fill out a school readiness survey, evaluating their students’ abilities. The teachers were unaware of the children’s viewership status. The children who watched Sesame Street more frequently were consistently marked as better prepared for school than their counterparts who rarely, or never, watched the show (Bogatz and Ball, 1971).

More current studies, conducted decades after the Bogatz and Ball research, continue to validate the impact of Sesame Street on young children, as well as the long-term effects of early viewership on older students. Even after removing extraneous contributing factors, such as parental involvement in education and preschool attendance, the studies continue to affirm that low-SES children continue to make larger gains over their higher SES peers in the ability to recognize letters and tell imaginative, yet realistically connective stories, when pretending to read. Furthermore, first and second graders who regularly tuned in to the program as preschoolers are often reading earlier on their own and require less remediation (Zill, 2001). One study went as far as to evaluate high school students who had watched children’s educational television, Sesame Street in particular, at a young age, in academic skills. Those high school students who watched more educational programming statistically had higher grades in English, Math and Science, used literature more often and placed academic performance high on a value list of achievement importance (Anderson, Huston, Schmitt, Linebarger, and Wright, 2001).

Combating Stigmas and Validating Curriculum Goals

Initially the stigma of what naturally must be the boring nature of an educational television program was something that the team at the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) had to overcome, even within themselves. In order for viewers to enjoy a program, entertainment and the ability to hold attention is key. Palmer recalls one member of the staff became “terribly agitated” at the thought of addressing a measurable curriculum outcome statement (“The child will…”) in not just every show, but every skit. The head writer at the time, Jon Stone, was instrumental in reassuring the creative team that the curriculum need not set the tone for the show but that having a set curriculum goal to start with leant itself to productive creativity, rather than detracting from it (Palmer, 2001).

The show also had to be developed in such a way that watching episodes in succession was not required. As repetition is integral to reinforcement, this could have led to disaster; instead 2,400 individualized segments, each corresponding to a distinct learning goal, were developed to be used interchangeably. The first season of Sesame Street consisted of 26 weeks at 130 episodes. 40 segments were to be used in each episode (Palmer, 2001). If every show were unique, the creative team would have had to come up with 5,200 individual segments. In an effort to structure the show to afford repetition without sacrificing content, the creative team chose to highlight three letters per week, 2 consonants and 1 vowel (at 3 times to address phonetic differences). The 12 week schedule would be repeated once, leaving 2 additional weeks for experimentation of format (Palmer, 2001).

Responding to Critics

Critics of educational television argue that watching a television program is simply a passive exercise. Palmer, along with other researchers at the CTW, sought to provide evidence to the contrary by using a method he coined as the “distraction technique.” By using separate audio/visual stimuli which were set to change every 7.5 seconds, like projected patterns from a kaleidoscope or slides images that were not brighter or louder but still in direct competition with projected clips from Sesame Street, researchers could effectively gauge the successfulness of clips to hold a viewers’ attention. It was further found that anything confusing would be ignored (Palmer, 1988; Gladwell, 2000). The results of this research directly impacted how clips were created as well as which ones were deemed effective enough to use in broadcast.

Learning is often tied to emotional experience as well as cognitive process. Educational television programs, such as Sesame Street, Square One Television and 321 Contact may have the ability to present material in one clip that lessens learner anxiety towards a particularly intimidating subject, such as math or science. Evaluating programs for entertaining and effective presentation methods of material often seen as difficult can be of great assistance in lesson planning for students who have trouble learning by more traditional methods. Critics are correct in arguing that edutainment is not a replacement for traditional educations, however edutainment can be a catalyst in fostering student skill development and help motivate them by providing a starting point. This follows constructivist learning theory, as learning is based on prior knowledge and experience.

Recreating the Model

In the 1990s, commercial networks geared towards children’s programming, such as Nickelodeon and Disney, started to branch out into the realm of educational broadcasts. A new format that highlighted characters breaking the imaginary fourth wall, asking children for answers to questions, clues, and both physical and verbal response, served to challenge critics who harped on the idea of passive viewing with no interactivity. The first show to include this question, followed by meaningful pauses for reflection and answer, format was Nickelodeon’s Blue’s Clues (Gladwell, 2001). Following the immense popularity of Blue’s Clues, other shows such as Dora the Explorer and Mickey Mouse Clubhouse were created to follow a similar format, trading strings of 2 minute clips strung together for one main storyline that children follow along with for a whole 24 minute episode, answering questions when characters strategically pause. These shows, also born out of extensive research, serve as both competition and successors to the still popular Sesame Street. They not only present early learning concepts such as shape and color recognition and counting skills but also promote and develop problem solving skills.

The Importance of Viewership

As in commercial television, viewership is an integral piece in determining the success of a program. Financially, the bigger the audience, the less production cost is expended per viewer. The more people who watch a program, and enjoy it, the more likely that word of mouth recommendations will spread and viewership will increase exponentially. Viewer preferences needed to be determined and incorporated into the design of the show. Palmer states, “Unlike the classroom teacher, Sesame Street had to earn the privilege of addressing its audience, and it had to continue to deserve its attention from moment to moment and from day to day” (Palmer, 2001). A lack of viewership often results in cancellation of programming.

In the case of Sesame Street, aside from strictly addressing curriculum, writers and producers were also concerned with creating adult-friendly content. To this end, elements of more sophisticated humor, such as play on words and parody of popular culture, were often infused into the program, without detracting from the educational aspect and distracting younger viewers with confusing language/concepts (Gladwell, 2000). Creating a children’s program which parents could actually enjoy, was a huge goal key to driving viewership.

Also key to gaining viewer loyalty is addressing what parents view as important lessons for their children. If parents understand the value of standard alphabetical and numerical conventions and see these lessons frequently portrayed in an entertaining way, the more likely they are to continue tuning in to the program. Children who display understanding and usage of lessons, independent of the show, further cement the validity and importance of the medium in their own lives by processing, incorporating and showing new knowledge. This speaks to constructivist learning theory. Often this also functions as an esteem-booster not only for the children, but for their parents as well. Pride in their children’s achievement, displayed through children’s expression of new knowledge in a relevant manner, serves to bolster the importance of tuning in to educational programming.

The following are examples of past and present Edutainment television programming spanning various target audience ages:

Sesame Street Mr Rogers Neighborhood Blues Clues Dora the Explorer Mickey Mouse Clubhouse Square One Television 3-2-1 Contact Mr. Wizard's World Beakmans World Bill Nye The Science Guy

Unintentional Edutainment in Television

Not all educational television shows may be categorized as such. Teachers may find relevant lessons in fictionalized material. It is important to note that teachers must validate the information being presented as based on actual facts before using it to enhance material. For instance, a medical drama may present a very important lesson regarding giving the wrong dosage of medicine to a certain type of patient (i.e. Giving aspirin to a child may result in Reye's syndrome.. Though originally written as a dramatic piece of fictional entertainment, screening this clip of story for medical students, or even children preparing to be caregivers of children, could potentially save lives. Less dramatically, it presents medical fact in a relatable fashion. Some television programs, in an effort to capitalize on retail success, may also release a line of edutainment products which correspond to their theme.

Edutainment and Technology

Education may be entertaining by the way it has been designed. Technology allows education to have an entertaining delivery and entertaining interaction.

- Educational software

- Educational websites available online

- Much of the audiovisual content in places such as Youtube

- Entertaining and interactive spaces and sites used in distance education based out of real schools, such as UBC’S MET program

- Virtual classrooms, such as seminars/lectures that exist in sites such as Second Life

Digital edutainment often alleviates the need for a traditional teacher and a traditional classroom. This has caused both praise and criticism towards edutainment and technology.

Edutainment and Gaming

With it's humble beginnings in the 1970's with game consoles such as Atari, gaming has exploded in the 1990's to the present. From Atari tennis to today's first-person shooter games, gaming is experiencing unprecendented growth. It is predicted to grow a further 10% by 2010. It cited several factors, including rapid teen growth, increasing numbers of female gamers, and rising youth incomes (Smith, 2006).

There has been considerable growth in educational games as well, targeting all age groups. However, the real growth in games are the console gaming platforms such as Playstation 3, PC, XBOX 360 and the Nintendo Wii.

In the past decade, gaming has taken on a new dimension with the internet, where gamers can play each other and interact with each other via networks locally and around the world. The main difference between educational games and traditional console games is that educational games focus on learning first, entertainment second. In console games, entertainment is paramount, with any learning being a by-product. However, there are certain console games that have a decidely more educational slant, namely The Sims series. The Sims are a fictional family where the gamer helps simulate their everydays lives. Moreover, the Sim series from Electronic Arts challenges learners to emulate an entire entity such as SimEarth, SimCity, SimPark and SimFarm.

There are now games that "train your brain." These games are to stimulate the player mentally and improve cognitive abilities (such as processing speed and short-time memory). The most popular is Nintendo's Brain Age. These games are played on the Nintendo's DS system which incorporates a double screen (one to read and one to write your answers). Brain Age "trains" your brain with timed mathematic calculations, short-term memory exercises and deduction situations.

Serious games are developed without commercial sale in mind. These games are created for the sole purpose of training and simulation for various agencies such as governments, medical outfits, and corporations. These games generally run on PC's and game consoles.

The following are examples of educational games:

Carmen Sandiego Oregon Trail Starfall Knowledge Adventure

Educational Support of Computer Gaming

Psychologist Dr. David Lewis carried out a study on information retention in 2000 on 13 and 14-year-old children. His research found students learned more effectively from information presented in the audiovisual form provided by a video game in comparison to facts from a printed page. Dr. Lewis discovered "more than three-quarters of the children absorbed facts contained in a historical video game as opposed to just more than half who were presented with the same information in written form." (BBC News, 2000)

Dr. Henry Jenkins, the director of Comparative Media Studies program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology believes video games can revolutionize education. In a podcast interview on IT Conversations, he states that edutainment "has developed a bad name mostly because of the work done in the 1980's when the technology wasn't there and the teachers weren't ready. Edutainment products tended to have all the entertainment value of a bad lecture... now the system is right, there is a generation of teachers who grew up playing games and they understand what it can do. The technology is more robust and allows you to have a depth of experience. And we have new models of thinking about education through games that I think are going to pave the way."

Dr. Jenkins further states, "All education that's good is entertaining... we talk less about fun and more about engagement... a lot of times games aren't particularly fun, they're hard work... If you ask a kid, 'What's the worth thing you can say about a bad homework assignment?' They'll say it's too hard. If you ask them what you can say about a bad game, they'll say it's too easy. Kids will stay up late engaging with a problem in a game to beat it. They'll give up very quickly on a problem set or a homework assignment. So, the challenge is to harness the holding power of games, the sense of engagement the games produce to kids to think more deeply about the subject matter."

The TEEM Report

The United Kingdom government commissioned a group of educators to find ways in which "games support the learning and teaching of curriculum content." The research is from the group Teachers Evaluating Educational Multimedia (TEEM). The TEEM organization now evaluates educational software for teachers and administration. The study looked into the habits of 700 children aged seven to 16.

In 2002, the TEEM organization released their findings in the "Report on the educational use of games." The study concluded that simulation and adventure games - such as Sim City and Roller Coaster Tycoon, developed children's strategic thinking and planning skills.

A summary of their findings include:

1) Games provide a forum in which learning arises as a result of tasks simulated by the content of the games, knowledge is developed through the content of the game, and skills are developed as a result of playing the game.

2) It seems that the final obstacle to games use in schools is a mismatch between games content and curriculum content, and the lack of opportunity to gain recognition for skill development. This problem is present in primary schools, but significantly more acute in secondary.

3) Many of the skills valuable for successful game play, and recognized by by both teachers and parents, are only implicitly valued within a school context. Teachers and parents both valued the conversation, discussion, and varied thinking skills demanded by some of the games employed. However, these alone could not justify the use of the games within a crowded school curriculum.

To enhance the value of the computer game in a classroom setting, it is "important for teachers to have some kind of record of what each group has done during a session of gaming" (McFarlane, 2002 pg. 10). The games need to be able to record scores so they can be tracked of what has been achieved. Teachers have indicated the games most valued and successful are games which have a clear progression and adaptable for students of different abilities. The games must develop scenarios that challenge and engage children, rather than reproducing text books on the screen.

The report indicated some problems teachers faced with the use of computer games. Many teachers "found it hard to justify using resources whose value lay in thinking alone, however effective that resource might be at developing thinking skills" (McFarlane, 2002 pg. 32). Also, teachers found it difficult justifying the use of simulation or adventure games during school time because their content did not map the UK curriculum.

McFarlane responded by suggesting if educational material could be built into the games then the games could be used in the classroom legitimately.

Edutainment is also valuable at the high school level, where movies that take place during a certain era can be shown to help stimulate discussion and enhance the relevance of the material being covered. For example, “Saving Private Ryan”, helps bring to life some of the battles and challenges that were faced during the war. The movie on its own is not education, but it does get the students’ palette ready and give them a reference point. In addition to movies, programs such as “How things are Made” is excellent in showing the manufacturing process, and the “Apprentice” can be a valuable discussion starter for Business classes. Programs such as “Holmes on Homes” are excellent for trades and construction classes.

Physical Benefits of Gaming

Advanced in technology have taken participants from pressing to buttons on handheld controllers to using full motion and gestures, recognized by optical sensors. Where traditional controllers addressed development of fine motor skills and hand eye coordination, optical recognition opens the physical benefits to include gross motor skills. Nintendo Wii, Playstation 3 Move and Kinect enabled XBox 360 consoles are being used in physical education classes as well as by special education teachers to promote use of the whole body in a visually engaging, gaming way. Students who may not be able to leave the classroom for outdoor physical activities can now participate with their peers. Profound mentally handicapped students who are in need of hand over hand assistance can now take part in activities that may have once been viewed as impossible.

Edutainment and the Workplace

Edutainment is not exclusive to children and youth. It has become part of adult education techniques and workplace training. Adults are self-directed learners that want to participate in their learning process. They are motivated by escape and stimulation in order to relieve boredom and breaks in routine (Leib, 1991). This has lead to the creation of edutaining workplace training. Simulations and training games allow adults to learn necessary workplace skills while being entertained.

" "

"

The above image is from New York City Hurricane Shelter Simulation Training in Second Life, developed by the CUNY School of Professional Studies (SPS) on behalf of the New York City Office of Emergency Management, by the Gronstedt Group.

Benefits of Edutainment

Stop Motion Artifact - Benefits of Edutainment -Lauren MacDonald

- Creates a more positive, affective environment for learning

- Attention, interest and memory may be heightened by multi-sensory media

- Improving the affective may also result in increased motivation and thinking skills

- May foster a more constructive learning environment

Criticisms of Edutainment

- Inaccuracy or unrealistic depiction of material due to the focus on the entertaining, artistic or subjective nature of entertainment

- Mental over stimulation may occur

- Human interaction time may suffer

- Passivity is associated with some media forms

- Stereotyping of characters, people or groups is a problem in popular media

- Association with the negative aspects of commercialism/capitalism

- As sources of edutainment often come from entertainment sources that are copyrighted, educators may require permission to use them or be required to pay for material

The K-12 Academics website criticizes edutainment as it "emphasizes fun and enjoyment, often at the expense of educational content." Critics argue that there must be teacher led instruction present when using any form of edutainment, otherwise, there are no forms of assessment that the learner has actually met the prescribed learning outcomes. It is also believed that the perceived lack of face-to-face interaction and collaborative learning of edutainment threatens normal socialization of students in a regular classroom. Moreover, the uneven global availability of information technology required to access and run digital media leads to a digital divide.

It is imperative when using edutainment in the classroom, that there be a context as to why a student is playing a game or watching a performance, rather than merely for entertainment purposes. The edutainment experience should serve to reenforce and enhance concepts, rather than simply presenting them in a more appealing way. Students should be able to take their experiences with edutainment and use them to create new pathways to knowledge, further constructing their learning and building upon prior knowledge.

Students as Producers of Edutainment

Technology continues to change at an exponential rate. As newer, faster, more advanced technology enters the retail marketplace, prices on earlier generation models decline, making these instruments more affordable than ever. This digital equipment is often far from outdated making it continually usable and at less of a cost to administrators and educators who might otherwise be reluctant to make purchases beyond budgets.

Students who produce their own edutainment, in the form of movies, games, animated stories, and other creative efforts are able to voice their knowledge in ways beyond traditional pencil and paper forms of expression and assessment. Students also have the advantage of knowing and appealing to their audience, when creating edutainment for their peers. Utilizing new pieces of technology, including recording equipment and editing software, give students the opportunity to learn new skills and technological literacy in addition to creating a deeper understanding of the subject they are creating their piece around. Calling upon their prior knowledge to create something new and foster a deeper understanding of a subject speaks to the constructivist view of learning.

Edutainment in Language Learning

Stop Motion Artifact - All Media is Edutainment -Scott Meech

In terms of Language Learning, edutainment can take a much broader definition. Not only media designed to educate, but any piece of media which arouses interest or amusement in a learner should be considered edutainment for the purposes of language learning. Media exposure levels (in the target language) has been shown to be correlated with second language proficiency. A study showed that although the Spanish educational system devotes more time to English language learning than the Icelandic system, Icelanders continually score higher on tests of English proficiency (Ortega, 2011); this was attributed to greater exposure to English speaking media in Iceland. The media which learners are exposed to, may not have the intended purpose to teach (many are designed to be pure entertainment), but have been shown to result in incidental language acquisition, particularly among children (Kuppens, 2010). More research needs to be done to test the effects of media exposure on language learning.

A Longitudinal Look at Edutainment

Stop Motion Artifact - A Longitudinal look at Edutainment - Jamie Ashton

See Also

Electronic Learning (E-Learning)

Additional Resources

- All Media is Edutainment Stop Motion Animation by Scott Meech

What is Edutainment? Stop Motion Animation by Rebecca Skucas

http://www.educationarcade.org/SiDA/learning

http://www.teach-nology.com/web_tools/games/

http://www.sharpbrains.com/tag/nintendo-brain-age

http://www.nobelprize.org/educational/

References

Anderson, D.R., Huston, A.C., Schmitt, K.L., Linebarger, D.L., & Wright, J.C. (2001). Early childhood television viewing and adolescent behavior. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66 (I).

Arnold, T.K. (2005) Edutainment: Smart programming?. Retrieved August 22, 2005 from http://www.usatoday.com/life/television/news/2005-08-22-dvd-edutainment_x.htm

BBC News Online (2000). Video games 'valid learning tools'. Retrieved February 27, 2008 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/730440.stm

Ball, S., & Bogatz, G.A. (1970). The first year of Sesame Street: An evaluation. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Bogatz, G.A., & Ball, S. (1971). The second year of Sesame Street: A continuing evaluation. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Cox, C. D., Cheon, J., Crooks, S. M., & Lee, J. (2017). Use of Entertainment Elements in an Online Video Mini-Series to Train Pharmacy Preceptors. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81 (1), pp, 1–13.

Dandashi, A., Karkar, A. G., Saad, S., Barhoumi, Z., Al-Jaam, J., & Saddik, A. E. (2015). Enhancing the Cognitive and Learning Skills of Children with Intellectual Disability through Physical Activity and Edutainment Games. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 11 (6).

Edutainment. 2012. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved February 26, 2012, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/edutainment

Fisch, S.M. (2005). Children’s learning from television. Televizion. 18. 10-14. Retrieved from: http://www.br-online.de/jugend/izi/english/publication/televizion/18_2005_E/fisch.pdf.

Gladwell, M. (2000). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. NY: Little, Brown & Company.

Guy, Retta., & Marquis, G. (2016). The Flipped Classroom: A Comparison of Student Performance Using Instructional Videos and Podcasts Versus the Lecture-Based Model of Instruction. Issues in Informing Science & Information Technology, 13, 1–13

IT Conversations (2005). Tech Nation. Podcast retrieved February 27, 2008 from http://itc.conversationsnetwork.org/shows/detail435.html

Jasinski, M. (2004). New Practices in Flexible Learning: Educational Infotainment. Australian Flexible Learning Framework. November 2004.

Kuppens, An H. (2010). "Incidental Foreign Language Acquisition from Media Exposure" Learning, Media and Technology, v35 n1 p65-85. March 2010.

Leib, S. (1991). "Principles of Adult Learning". Retreived January 23, 2009 from http://honolulu.hawaii.edu/intranet/committees/FacDevCom/guidebk/teachtip/adults-2.htm

Lynch-Arroyo, R., & Asing-Cashman, J. (2016). Using Edutainment to Facilitate Mathematical Thinking and Learning: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Mathematics Education, 9, 37–52.

McFarlane, A. (2002) Report on the educational use of games. Retrieved February 1, 2008 from http://www.teem.org.uk/

Ortega, S.G. (2011) Media Exposure and English Language Proficiency Levels: A comparative study in Iceland and Spain. University of Iceland. http://skemman.is/stream/get/1946/10035/25085/1/Thesis_12.sept.pdf

Palmer, E.L. (1988). Television and america’s children: A crisis of neglect. NY: Oxford University Press.

Palmer, E.L., & Fisch, S.M. (2001). The beginnings of Sesame Street research. In S.M. Fisch, & R.T. Truglio (eds.), “G” is for “growing”: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Skelton, S. (2001) Edutainment - The Integration of Education and Interactive Television. Retrieved 2001 from http://csdl2.computer.org/comp/proceedings/icalt/2001/1013/00/10130478.pdf

Smith, C. (2006) Trigger Happy: Video Game Explosion. Retrieved February 18, 2007 from http://www.straight.com/node/49134

Van Eck, R. (2006). Digital game-based learning: It's not just the digital natives who are restless. Educase Review, 41 (2), 1–16.

Wallden, S., & Soronen, A. (2004) Edutainment: From Television and Computers to Digital Television. Retrieved May, 2004 from http://www.uta.fi/hyper/julkaisut/b/fitv03b.pdf.

Zill, N. (2001). Does Sesame Street enhance school readiness? : Evidence from a national survey of children. In S.M. Fisch, & R.T. Truglio (eds.), “G” is for growing: Thirty years of research on children and Sesame Street. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.