Learning Commons:Content/Myths About Learning

Myth 1: Talent is everything!

Talent can help, but your attitude about learning is way more important. If you believe your learning abilities are fixed, you'll put up mental blocks that hinder your learning. For example, if you are used to getting straight A's you may tend to avoid risks that might take you out of your comfort zone and risk your perfect record. Conversely, if you believe you are not good at something (say math for example) you may lower your expectations,etc. Either way, those fixed beliefs will prevent you from opening up to new experiences that may have a profound impact on your learning. Students who have a 'growth mindset' about learning, and believe that they can really improve over time and with effort tend to take more chances, progress faster, and see risk and failure as part of the learning process (Dweck, 2006). "Research suggests that students who view intelligence as innate focus on their ability and its adequacy/inadequacy, whereas students who view intelligence as malleable use strategy and effort as they work toward mastery." (Schoenfeld, 1983). Mindset can have positive and negative impacts on learning: intelligence and ability are neither innate nor static. Our brains grow, change, and adapt as we use them.

A combination of motivation and focused effort in deliberate practice will really help you develop a deeper understanding. Deliberate practice is about more than just putting time in: it includes frequent feedback, repeatedly adjusting your approach, and a belief that you can learn and grow with effort. What you do is just as important as how often you do it.

|

References:

- Growth Mindset: Mindset Scholar's Network Retrieved: May, 29, 2018.

- Ambrose, S.A, Lovett, M.C. (2014) Prior Knowledge is More Than Content: Skills and Beliefs Also Impact Learning, in Benassi, V. A., Overson, C. E., & Hakala, C. M. (Editors). (2014). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Available at the Teaching of Psychology website: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php.

Myth 2: I only need one good method for studying.

Sometimes, study methods that worked in high school - just don't serve you well in university. If your tried and true study strategies aren't working, use a different approach. Monitor your learning, by measuring your knowledge against what you expect. Before you start studying, guess how it'll go. Predict your homework and test results, and see if you're accurate or not. Notice when your expectations fall short of (or overshoot) reality, and adjust your approach accordingly. This is called metacognition, and it's an important part of effective learning.

There's also some evidence to suggest that mixing it up (in terms of where, when and how we study and learn) promotes recall (Carey, 2015)

|

Myth 3: If it's easy, I must be learning.

Often, we are fooled into thinking we understand something, because terms or concepts sound familiar. You might find yourself feeling like you really understand the material, when your brain is really just responding to the fact that it's seen this exact material before. To add to that, if it is presented in a clear and pleasing manner, it might create an illusion of fluency. This is called a fluency bias or familiarity trap—when everything seems familiar, your brain doesn't have to work so hard, so it feels like you've mastered the material, even though you haven't. Try to mix things up as you're studying.

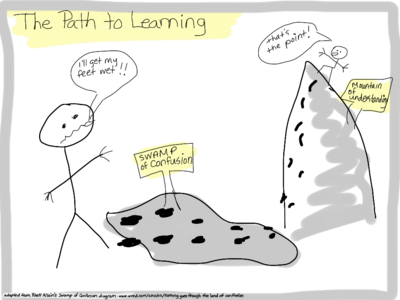

More and more, evidence suggests confusion is where deep learning lies. It might even be that some level of confusion activates parts of your brain which regulate learning and motivation, helping you achieve a greater level of understanding. If you're not confused, you might not be learning. See Learning Goes Through the Land of Confusion by Rhett Alan, a physics professor at Southern Louisiana University, for a brief explanation. Don't let yourself get discouraged if it feels like you aren't 'getting it': that's a good sign.

Other science educators have found support for the idea that confusion is important to learning. Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics education researcher, has done some interesting research on the topic—a summary of his findings can be found in this blog post. Another researcher and science educator, Derek Muller, has looked at the relationship between learning and video. Watch this video where he explains his findings and talks about the strengths and weaknesses of Khan Academy.

|

Myth 4: If I memorize enough to pass the test, I've learned it!

If you stay up all night cramming for a test, you'll probably pass. If you've got a test tomorrow and you haven't cracked a book, you don't have a choice. But have you really learned anything while you were cramming? Cramming doesn't give the brain time to process information and make critical connections necessary to retrieve it from memory later. If you have classes that build on previous courses, you'll wish you'd spaced out your studying. That's your note to self for next time.

Learning goes beyond your test scores: critical thinking analysis, applying principles to solve problems, the ability to assess your effectiveness, revise, and apply what you know are skills that you'll need through the rest of your life. If you have a test the next morning, you might have to pull that all-nighter, but you'll do better on the test and remember the material for longer if you spread your learning out, and use some of the strategies laid out here.

|

Myth 5: Planning is a waste of time.

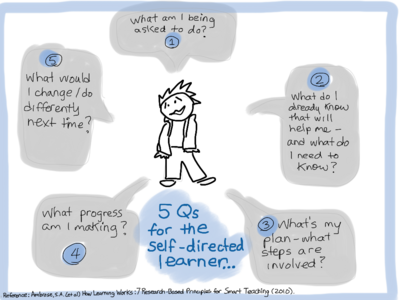

Being a self-directed learner requires planning.

Answering the 5 questions from the graphic above can help to build a disciplined approach which will help you tackle your academic work.

Planning can also help you develop a workable schedule for studying. "Research shows spacing study episodes out with breaks in between study sessions or repetitions of the same material is more effective than massing such study episodes. Massing practice is akin to cramming all night before the test." (Clark and Bjork, 2014).

Planning reduces stress, helps you avoid cramming, and builds skills in metacognition. Planning is an important part of any career or occupation, so learning to plan well contributes to your overall competency. Even learning to plan takes practice, so start early!

Reference:

- Clark, C.M., Bjork, R.A. (2014) When and Why Introducing Difficulties and Errors Can Enhance Instruction, in Benassi, V. A., Overson, C. E., & Hakala, C. M. (Editors). (2014). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Available at the Teaching of Psychology website: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php.

Myth 6: Failure should be avoided at all costs.

"Every success is built on the ash heap of failed attempts." This reminder from Prof. Michael Starbird (U of T at Austin) offers a good reason not to fear failure. Failure doesn't often feel good, but it may be your best teacher. In fact, in their book 5 Elements of Effective Thinking, professors Edward Burger and Michael Starbird, say that failure is, in fact, an important foundation on which to build success. But, as they point out seeing failure as an opportunity for learning requires a fresh mindset. "If you think I'm stuck and I'm giving up; I know I can't get it right, then get it wrong. Once you make the mistake, you can ask, why is THAT wrong? Now you're back on track, tackling the original challenge." Failure is an important aspect of much creative work - though it goes by a different name - iteration. Iteration is important in refining, working though problems, starting small and refining until more can be added. Iteration is a feature of work in design, science, technology and really any field where innovation is important.

|

Reference:

- Burger, E. B., & Starbird, M. P. (2012). The 5 elements of effective thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.