Learning Commons:Content/Learning Challenges/Failure

The Problem

I failed a course. You've failed your first big exam or maybe an entire course or two. Now what? First off, failure it not unique to you, it is common. It can often be one of the most powerful teachers we have. Recovery (and even using failure as a catalyst to learning), requires a shift in perspective. Instead of beating yourself up, ask "what can I learn from this?" In order to make good decisions about what to do next, you need to understand what happened. Here are some common scenarios that may lead to your first "bomb:"

Waiting too long to seek help

This is a common mistake for first year students who are often nervous about meeting with their profs outside of class. You may feel like you will be judged or that your questions are stupid. It may be helpful to know that your questions will likely not be new to your professors - they've likely heard it before from many students before you and can offer some immediate and specific advice to help you. Remember that your professors and TAs are here to help you learn and they want to see you succeed.

Not doing the work

Maybe you got by in high school when you skipped the readings or didn't work through problem sets outside of class. But in university, you are aiming for deep, conceptual understanding. This kind of learning takes practice over time and in many forms. After all, you are preparing to use what you've learned in a professional setting after you graduate - so you need to spend the time to learn it well. You may need to ask yourself why you are not making time for the work outside of class. The answer to this question will lead you to a strategy for improving your self discipline.

Not going to class

Every student makes decisions about when, why and whether or not to go to class. Missing too many classes can be de-motivating, especially of you are missing important lectures or learning activities that help you make sense of the course content. Again, you need to ask yourself (and answer honestly), why you are missing classes. Conflicting schedules, poor health or sleeping habits can be contributors and are fixable.

Ineffective study methods

Cramming, multi-tasking, re-reading (without self testing) are all methods that fool us into thinking we are learning and being productive with study time. Reflecting on your own study methods and a willingness to try new approaches is a good first step.

The Myths

The following myths about learning are relevant to the challenge of failure.

Myth 5: Planning is a waste of time.

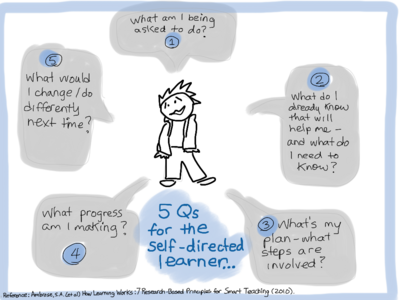

Being a self-directed learner requires planning.

Answering the 5 questions from the graphic above can help to build a disciplined approach which will help you tackle your academic work.

Planning can also help you develop a workable schedule for studying. "Research shows spacing study episodes out with breaks in between study sessions or repetitions of the same material is more effective than massing such study episodes. Massing practice is akin to cramming all night before the test." (Clark and Bjork, 2014).

Planning reduces stress, helps you avoid cramming, and builds skills in metacognition. Planning is an important part of any career or occupation, so learning to plan well contributes to your overall competency. Even learning to plan takes practice, so start early!

Reference:

- Clark, C.M., Bjork, R.A. (2014) When and Why Introducing Difficulties and Errors Can Enhance Instruction, in Benassi, V. A., Overson, C. E., & Hakala, C. M. (Editors). (2014). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Available at the Teaching of Psychology website: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php.

Myth 6: Failure should be avoided at all costs.

"Every success is built on the ash heap of failed attempts." This reminder from Prof. Michael Starbird (U of T at Austin) offers a good reason not to fear failure. Failure doesn't often feel good, but it may be your best teacher. In fact, in their book 5 Elements of Effective Thinking, professors Edward Burger and Michael Starbird, say that failure is, in fact, an important foundation on which to build success. But, as they point out seeing failure as an opportunity for learning requires a fresh mindset. "If you think I'm stuck and I'm giving up; I know I can't get it right, then get it wrong. Once you make the mistake, you can ask, why is THAT wrong? Now you're back on track, tackling the original challenge." Failure is an important aspect of much creative work - though it goes by a different name - iteration. Iteration is important in refining, working though problems, starting small and refining until more can be added. Iteration is a feature of work in design, science, technology and really any field where innovation is important.

|

Reference:

- Burger, E. B., & Starbird, M. P. (2012). The 5 elements of effective thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

The Strategies

|

The Toolkits

The Links

- UBC Policies on Academic Standing.

- Academic Advising

- Optimizing Learning in College: Tips from Cognitive Psychology

Videos

- College Info Geek: When You Just Can't Motivate Yourself to Study, Consider This.

- College Info Geek: My 3 Tier Planning System for Getting Things Done

- College Info Geek: How to Bounce Back from Failure.

Health and Wellness at UBC: