Just Food Project: Food Justice Primer

Introduction

“Food can be a powerful metaphor for the way we organize and relate to society. [...] Through food we can better understand our histories, our cultures, and our shared future.”

- Levkoe (2006)

Food justice represents "a transformation of the current food system, including but not limited to eliminating disparities and inequities" that constrain food choices and access to good food for all.[1] This requires actively analyzing and reflecting on the structural causes that permeate the food system and society broadly, leading to unequal access to food for different groups.[2][3][4] Food justice entails ensuring the fair distribution of benefits and burdens of where, what, and how food is grown, produced, transported, distributed, accessed, and consumed.[1]

Many different definitions of food justice exist. A core tenet of food justice is local specificity; communities must define this term for their own purposes.[5] Formulating place-based definitions allows individuals and communities to understand and locate themselves within the systems that allow for injustices to be reproduced. To do so requires self-reflexivity and a critical understanding of equity, power, justice, intersectionality, and positionality (see Glossary for definitions of terms). The purpose of this module is to provide an introduction to food systems and food movement concepts in relation to systemic and intersecting forms of oppression. Corresponding activities and assessments will foster self-reflexivity and critical analysis of food system concepts.

Key Themes: Defining Food Justice; Food Security; Labour; Race; Gender; Examples & Forward Action; Class

Learning Outcomes

- Identify one’s own positionality in relation to the food system.

- Distinguish between equity, equality and the three forms of power (personal, positional, and systemic power).

- Identify the three types of (in)justice (epistemic, distributive, procedural) as they relate to food systems.

- Define the concepts of food justice, food security, and food sovereignty so as to be able to identify the concepts in practice.

Background

Introduction to Food Justice

The negative impacts of industrial agriculture, food insecurity, and diet-related health issues are becoming increasingly apparent, leading us to ask—how do we create a better food system? The root causes of, impacts on, and solutions to food systems issues are complex, requiring not only knowledge of food systems sustainability (such as sustainable growing methods and food preparation skills) but also knowledge of the larger systems that shape how we cultivate, prepare, transport, consume, and dispose of food.

Current statistics indicate that people’s food needs are not being met—there are increasing rates of hunger, poverty, and imbalances in the distribution of power and resources.[6][7] Decision-making and democratic processes within the food system are increasingly placed under the control of corporations and market forces, which distance people from the production and consumption of their food.[8][4][9] In its present state, the food system poses “significant challenges to social justice, ecological sustainability, community health and democratic governance”.[4][2]

So, how do we transform the food system? The reproduction of food injustices are inherently issues of equity, power, and justice. By discussing these central aspects of food justice work, we can begin to understand how equity relates to the food system, and how it can ultimately inform the practice of food justice. In addition, making distinctions between food justice, food sovereignty, and food security will lay the groundwork for unpacking the synergies and contradictions between each movement. This primer introduces allyship, positionality, and intersectionality to provoke critical thinking and self-reflexivity.

How is Food Injustice Produced?

The current global food system has been formed through multiple forms of oppression, including classism, racism, and sexism, which are rooted in imperialism, colonialism, and patriarchy.[10] Foundational to the capitalist food system is slavery, exploitation, and the dispossession of land, labour, and products of marginalized groups—including women, the poor, and people of colour.[11] These systemic inequalities predominantly impact marginalized communities and restrict access to healthy, culturally appropriate, and affordable foods.[10] They often manifest in environmental and social injustices, including poor working conditions for foodservice workers and farmworkers.[10]

Positionality and Intersectionality

The term ‘positionality’ is used by feminist scholars, including the philosopher Linda Alcoff who coined the term, to describe how our worldviews are affected by out lived experiences and social identities (such as those implicated by race, class, and gender).[12] Understanding positionality within the food system is important because many injustices are a result of social choices, traditions, institutions, and legal and economic structures.[7] For example, the hazards of pesticide exposure are often most acutely felt by racialized migrant field workers[13] whose poor working conditions are a result of social choices regarding wage and status.[14]

Societies make distinctions between social groups and between individuals, resulting in assigned roles and statuses. Kimberlé Crenshaw first used the term ‘intersectionality’ to indicate how social differentiation occurs through interactions between ‘markers of difference’ (for example, social identities formed by gender, race, age, ability, and class).[15][16] To understand different experiences, it is necessary to analyze how social identities intersect and interact.[17]

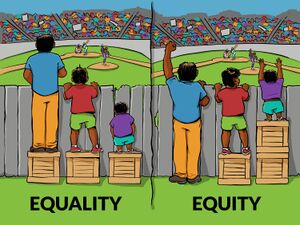

Equity vs. Equality

Often, the terms equity and equality are used interchangeably, but they have important differences. When applying a food justice lens, equal treatment of actors and agents within the food system may not lead to equitable outcomes.[18] Equality means that each person within a community or system is treated the same by an actor or initiative, regardless of systemic and historical injustices they have endured or privileges they have been accorded. In contrast, equity refers to treating individuals “according to their circumstances” so that they can experience similar outcomes to the rest of the community or system.[19] An equitable approach requires careful consideration of actors’ positionalities and intersections within society as opposed to a universal approach that may be superficially seen as ‘equal’.

Power

There are multiple forms of power that can inhibit or promote an individual's or group’s agency within a food system. The level of personal power, positional power in hierarchies, and systemic power an individual possesses varies based on context. For example, an individual may have more personal power in some groups than others based on how their values align. Or, a group may lack the three forms of power—personal, positional, and systemic—due to their positionality and intersection of identities.[20]

Justice

The Just Food learning modules focus on three forms of justice: epistemic justice, procedural justice, and distributive justice. Distributive justice refers to the equitable distribution of benefits and burdens. Procedural justice is built upon equitable inclusion within decision-making and participatory processes.[21] Epistemic justice asks the question, “Whose knowledge counts?” and brings attention to ways of knowing that are normalised or stigmatised and made invisible.[22] Typically, epistemic injustice can underlie distributive and procedural injustices because power struggles between different ways of knowing and what is considered to be real or true can inform decision-making and distribution of resources.[22] However, the manifestation of injustice within a system is not a linear process and these forms of justice influence each other in various ways.

Food Justice, Food Security, and Food Sovereignty

Food security is defined as a condition in which all people have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences.[23] At the outset, food security appears to be an ideal goal, however the pursuit of food security often avoids discussion of the social control of the food system—for example, by ignoring the historical and structural conditions that have led to inequalities.[24] Moreover, initiatives aimed at mitigating food systems issues are often individualistic and consumer-based, rather than addressing social justice and environmental sustainability for the collective benefit.[4] These initiatives also primarily target white, privileged, middle-class audiences.[4][5][11][25] Academics and activists critique these approaches for obscuring the intersections between food systems and social justice by concealing the historical and contemporary racist, classist, and gendered features of the food system.[11] This risks reproducing the economic exploitation and political oppression of marginalized communities.[4][26]

In response, proponents of food justice believe that changing our food systems demands a different approach. Understandings of food justice continue to evolve and are not universally agreed upon, but often refer to communities exercising their right to grow, sell, and eat fresh, nutritious, affordable, culturally appropriate, and locally-grown foods. Historical and contemporary injustices, including violations of the well-being of the environment, workers, and animals, must also be considered.[27][28] Food justice differs from food security as it involves addressing the causes and impacts of inequality both within and beyond the food system—as racism, exploitation, and oppression.[29]

Similarly, the food sovereignty movement advocates for “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems".[30] The movement works to help producers and consumers regain power and agency within the food system.[31]

The table on page 3 of Food Security, Food Justice, or Food Sovereignty? by Eric Holt-Giménez[32] is helpful to understand current food regimes and movements. Food regimes are a way to conceptualize the food system by looking through an economic lens at the “rule-governed structure of production and consumption of food on a world scale”.[32] While it is an academic tool, the examples listed underneath each heading can help to distinguish food justice, food sovereignty and food security.

Allies and Accomplices

Once we recognize our positionality, what do we do with that new frame of knowing? How do we move forward from here?

Similar to food justice, allyship is not an outcome that is easily achieved. Food justice and allyship are both goals to work towards since widespread, large-scale systemic change would be required in order to fully manifest these ideals. Being "an ‘ally’ is not an identity, it is an ongoing and lifelong process that involves a lot of work,” and requires recognizing one’s complicity in oppression.[33] Allies work in solidarity with groups that are predominantly marginalized by recognizing their privilege and challenging institutional and systemic oppressions that perpetuate inequity.[33][34]

However, many organizations and activists feel that the term ally has been co-opted by privileged and self-proclaimed allies, who have advanced their own careers off of the struggles of groups they are trying to support, producing an ally industrial complex and effectively rendering the term ‘ally’ useless.[35] The term accomplice is put forth as an alternative that centres a “fiercely unrelenting desire to achieve total liberation, with the land and, together” and the need for those who hold privilege to become “complicit in a struggle towards liberation,” instead of the temporary shows of support provided by allies.[35] In the field of pedagogy, Sheridan highlights the need to reflect on and acknowledge one’s own complicity in systems of oppression as a key step to working towards change and action, and this applies to food systems work as well.[36]

Moving forward, it is valuable to interrogate how learners, community members, and scholars can work towards becoming active accomplices through practicing solidarity in conducting research, questioning unequal positions and power dynamics in community work, and working with those most affected to create equitable responses to the needs of marginalized communities.[37]

Key Terms

Facilitator Note: Many definitions exist for the following topics—these definitions have been chosen after conducting a thorough literature review, however, may be adjusted if deemed necessary.

- Ally: An ally is a person who commits and makes efforts to recognize their privilege (based on gender, class, race, sexual identity, etc.) and works in solidarity with oppressed groups.[38] While the term ally is used in these modules, there are several critiques of it; see accomplice for another understanding of working towards practicing solidarity to lead to collective liberation.

- Accomplice: The term accomplice has emerged in critique of those who have co-opted the term ally, advancing their own careers off of the struggles they are trying to support, producing an ally industrial complex, effectively rendering the term useless.[35] Accomplice is put forth as an alternative to centre a “fiercely unrelenting desire to achieve total liberation, with the land and, together” and the need for those who hold privilege to become “complicit in a struggle towards liberation,” instead of the temporary shows of support provided by allies.[35]

- See this guide that provides examples of distinguishing between the actions of actors, allies and accomplices. While it is an oversimplification, and written for a white audience focusing solely on racial justice, it is a starting point for those working to show solidarity with different marginalized groups to which they may not belong.

- For White/white-passing educators and learners, here is a great guide on how to move from being an actor to ally to an accomplice in our collective fight for racial justice. This is a great place to start if you find yourself asking “What can I do? How should I evaluate my actions and intentions?”

- Equity: Equality refers to treating each person within a community or system in the same way. Equity refers to treating individuals “according to their circumstances” so that they can experience similar outcomes to the rest of the community or system.[39] An equitable approach requires careful consideration of actors’ positionalities and intersections within society as opposed to a universal approach that may superficially appear to be equal.

- Food Justice: Understandings of food justice continue to evolve and are not universally agreed upon, but most see food justice as meaning "a transformation of the current food system, including but not limited to eliminating disparities and inequities" that constrain food choices and access to good food for all[1] and communities exercising their right to grow, sell, and eat fresh, nutritious, affordable, culturally appropriate, and locally grown foods. The well-being of the environment, workers, and animals must be considered simultaneously.[28] Food justice involves addressing the causes of inequality both within and beyond the food system—such as racism, exploitation, and oppression.[40] This means actively analyzing and reflecting on the structural causes that permeate the food system and society broadly, leading to unequal access to food for different groups.[2][3][4]

- Food Security: Food security is considered a basic human right by the United Nations—it is actualized when all people have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences.[24] The concept of food security usually emphasizes physical and economic access to food; the FAO emphasizes that an increase in food insecurity at the global scale can contribute to economic slowdowns and increased conflict.[41] The food security paradigm often compares the total amount of production to the average needs of the population to measure food insecurity.[41]

- Food Sovereignty: "Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems."[41] The concept of food sovereignty was introduced and championed by La Via Campesina in 2007, a global peasant movement working to enact their food sovereignty by advocating for workers’ and women’s rights and fighting against land grabs and the spread of GMOs.[42]

- Food System: A food system is a “complex web of activities,” and a food systems lens aims to look holistically at food, including its “production, processing, transport and consumption”.[43] Viewing food from this systems lens relies on a relational way of viewing processes, and spans many disciplines including economics and governance, food cultivation and environmental science, and nutrition and population health.[43]

- Intersectionality: Kimberle Crenshaw, a Black feminist legal scholar, first used the term ‘intersectionality’ to articulate how social differentiation occurs through interactions between ‘markers of difference’ (for example, social identities formed by gender, race, and class). To understand different experiences, it is necessary to analyze how social identities intersect and interact.[15][16][17] See this helpful introductory video from Teaching Tolerance.

- Justice

- Distributive Justice: Distributive justice concerns the fairness of distribution or division of something among several people or groups, whether it be a benefit (e.g. Work wages) or a burden (e.g. Taxes).[44]

- Epistemic Justice: Epistemic justice relates to the privilege or oppression of different ways of knowing, understanding and communicating, as well as different systems of thought.[45][22] In North America, there are different systems of thought. For instance, Western scientific thought, which attempts to separate science from religion and philosophy. There are also various Indigenous understandings based on traditional ecological knowledge which is a more holistic understanding “of the rules and responsibilities that govern the relations between people and all components of the natural world, whether human or non-human.”[22] When Western ways of knowing inform policies that cause harm to Indigenous groups and undermine their sovereignty and right to self-determination, this is a structural epistemic injustice, rooted in histories of power dynamics. Another example of epistemic injustice in the context of the settler nation of Canada would be federal laws that assume Canada has control over Indigenous peoples and their territories.[46] Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Report demonstrated that longstanding Indigenous laws and institutions are denigrated and ignored in discussions of sovereignty, self-determination, justice claims, and reconciliation. The report states that for reconciliation to be possible, non-Indigenous Canadians need to unlearn what is taught in the ‘official’ accounts of history and learn about the histories of laws, practices, and traditions as told by Indigenous Canadians. Who gets to tell and record the ‘history of Canada’ shapes the collective interpretation, in turn shaping the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. Questioning who gets to tell the stories and acknowledging how these stories shape our collective history is an example of pursuing epistemic justice.

- Procedural Justice: Procedural justice results from following a ‘fair procedure’ – which concerns the fairness of how information is gathered or how a decision is made (not the decision made or information gathered itself).[44][21] For example, consider information provided by consultation with all parties involved versus information provided without adequate consultation.

- Positionality: The term ‘positionality’ is used by feminist scholars, including the philosopher Linda Alcoff who coined the term, to describe how lived experiences and social identities (such as those implicated by race, class, and gender) shape our worldviews.[12] These identities are not essentialized or fixed to certain characteristics; they are markers of relational positions and are fluid, shaped by “socially constructed positions and memberships to which [they] belong”.[47]

- Oppression: “A pervasive system of supremacy and discrimination that perpetuates itself through differential treatment, ideological domination, and institutional control. Oppression depends on a socially constructed binary of a dominant group (though not necessarily more populous) as being normal, natural, superior, and required over the ‘other’. This binary benefits said group, who historically have greater access to power and the ability to influence the process of planetary change and evolution.”[48] Examples of oppression include racism, classism, and heterosexism.[49]

- Anti-oppression: Anti-oppression is the “strategies, theories, actions, and practices that actively challenge systems of oppression on an ongoing basis”.[50] The Anti-Oppression Network centres personal responsibility in their understanding of practicing anti-oppression, stating that anti-oppression is not only confronting individual examples of oppression but “also confronting ourselves and our own roles of power and oppression in our communities and the bigger picture.”[51]

- Power

- Positional Power: Positional power comes from positions within hierarchies which offer more privilege to those with higher positions—for example, hierarchies based on age, experience, or professional titles.[20]

- Personal Power: Personal power is the power within each individual to take action, make decisions, and participate. Personal power can be enhanced or limited depending on the influence of systemic or positional power.[20]

- Systemic Power: Systemic power is built into socioeconomic relationships. Systems that hold power in society provide individuals and groups in control with significant power and privilege—for example, government, business, and education. The values of those who hold systemic power can create environments that increase barriers for those with less privilege or decrease barriers for those with more privilege.[20]

Activity Outline

Facilitator Notes:

- Time is provided as an estimate for each activity and may vary slightly depending on group size and discussion.

- Activities 1 and 2 are oriented towards those who do not have the lived experience of oppression in that they serve to illuminate privilege to those who may have been previously unaware and assume that the learner is likely white and of the middle class. Depending on learners’ experiences with understanding and acknowledging their own positionality in different contexts, learners may have vastly different responses to these activities. Facilitators should see the Facilitator Guide to equip themselves with tools to handle what may arise, such as microaggressions, and other resources to help them model reflexivity and vulnerability in order to support student learning. For learners who may have already engaged with issues of social justice and racial oppression, activities in the Module 4: Migrant Labour may be more suitable.

- Please note that many of these activities require building trust, gauging readiness, and co-creating both safer and brave spaces for participants to hear truths that may be challenging. Ensure that group guidelines are established before the activities are conducted to foster participation and the ability of participants to unpack their own thoughts and behaviours.

- Suggested assessments are embedded throughout each activity.

| Activity | Estimated Time | Associated Learning Outcomes | Activity Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Activity: Group Guidelines | 30 min | Define your role as facilitator and clarify the group’s expectations of you and each other, as well as foster a safe, respectful, and effective learning environment for participants. | |

| Activity 1: Reading Discussion | 45 min | 1.Identify one’s own positionality in relation to the food system.

2.Distinguish between equity, equality, and the three forms of power (personal, positional, and systemic power). 3. Describe the three types of (in)justice (epistemic, distributive, procedural) as they relate to food systems. 4. Define the concepts of Food Justice, Food Security, and Food Sovereignty to be able to identify the concepts in practice. |

This activity provides background reading and sample discussion activity to go through the readings. Choose one reading for each learning outcome. Assign the readings before class and offer prompts to encourage in-class discussions. Conduct an in-class discussion to debrief the reading and background material. |

| Activity 2: Power Flower | 45 min | 1. Identify one’s own positionality as it relates to the food system. | Facilitate participants in identifying their own positionalities. |

| Activity 3: Privilege Walk | 45 min | 1. Identify one’s own positionality as it relates to the food system. | Visibly demonstrate positionality in the classroom. This activity requires physical space. |

| Activity 4: Socialization Map | 30-45 min | 1. Identify one’s own positionality as it relates to the food system. | Explore the societal messages that construct participants’ identities or perceptions of their identities. |

| Activity 5: Equity vs. Equality | 25 min | 3. Distinguish between equity, equality and the three forms of power (personal, positional, and systemic power). | Distinguish between equity and equality. |

| Activity 6: Four Corners | 15-30 min | 3. Identify the three types of (in)justice (epistemic, distributive, procedural) as they relate to food systems. | Distinguish between procedural, epistemic, and distributive justice. |

| Activity 7: The Dot Activity | 20-30 min | 2. Distinguish between equity, equality and the three forms of power (personal, positional, and systemic power). | Conceptualize and enact power relations within the classroom setting. |

| Activity 8: Contrasting Orientations: Food Justice, Food Security, & Food Sovereignty (Advanced) | 45 min | 4. Define the concepts of Food Justice, Food Security, and Food Sovereignty to be able to identify the concepts in practice. | Identify and explain the drivers underlying efforts for Food Justice, Food Sovereignty, and Food Security and identify ways for participants to get involved in equity-oriented food system initiatives.

Note: This activity requires participants to conduct some research before completing the in-class activity. Part 1 of this activity is suitable as an introduction to the concepts. Part 2 is suitable for participants who already have some familiarity with the key terms and themes discussed in this primer, and allows them to identify areas they can be involved in their own community. |

| Activity 9: HEADS UP Analysis (Advanced) | 45 min | 2.Distinguish between equity, equality and the three forms of power (personal, positional, and systemic power).

4. Define the concepts of Food Justice, Food Security, and Food Sovereignty to be able to identify the concepts in practice. |

Understand and analyze common problems with campaigns and educational initiatives that fail to recognize the complexities of global issues.

Note: Suitable for participants who already have some familiarity with the key terms and themes discussed in this primer, as this activity requires a firm understanding of these topics. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Gottlieb, Robert; Anupama, Joshi (2010). "1: Growing and Producing Food". Food Justice, ix. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: MIT Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Allen, Patricia; FitzSimmons, Margaret; Goodman, Michael; Warner, Keith (2003). "Shifting plates in the agrifood landscape: the tectonics of alternative agrifood initiatives in Californi". Journal of Rural Studies. 19 (1): 61–75. doi:10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00047-5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Born, Branden; Purcell, Mark (2006). "Avoiding the Local Trap". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 26 (2): 195–207. doi:10.1177/0739456x06291389.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Levkoe, Charles Zalman (2011). "Towards a transformative food politics". Local Environment. 16 (7): 687–705. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.592182.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine; Slocum, Rachel (2015). "What does it mean to do Food Justice?". Journal of Political Ecology. 22 (1). doi:10.2458/v22i1.21076.

- ↑ Davis, Babara; Tarasuk, Valerie (1994). "Hunger in Canada". Agriculture and Human Values. 11 (3): 50–57. doi:10.1007/bf01530416.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Allen, Patricia (2008). "Mining for justice in the food system: Perceptions, practices, and possibilities". Agriculture and Human Values. 25 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1007/s10460-008-9120-6.

- ↑ Tarasuk, Valeria; Mitchell, Andy. (2020) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca

- ↑ Kneen, Brewster (1989). From land to mouth: understanding the food system. Toronto: NC Press.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Holt-Giménez, Eric (2018). "Overcoming the Barrier of Racism in Our Capitalist Food System" (PDF). Food First Backgrounder. Oakland, CA: Food First/ Institute for Food and Development Policy. 24 (1).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Slocum, Rachel (2007). "Whiteness, space and alternative food practice". Geoforum. 38 (3): 520–533. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.10.006.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alcoff, Linda (1988). "Cultural Feminism versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory". Signs. The University of Chicago Press. 13 (3): 405–436.

- ↑ Das, Rupali; Steege, Andrea; Baron, Sherry; Beckman, John; Harrison, Robert (2001). "Pesticide-related Illness among Migrant Farm Workers in the United States". International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 7 (4): 303–312. doi:10.1179/107735201800339272.

- ↑ Weiler, Anelyse; Otero, Gerardo (2013). "Boom in temporary migrant workers creates a vulnerable workforce, increases workplace inequality". Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Crenshaw, Kimberle (1991). "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color". Stanford Law Review. 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Crenshaw, Kimberle (1989). "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics". University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Intersectionality." In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 114-116. Vol. 4. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. Gale eBooks.

- ↑ JustHealthAction. (n.d.). Lesson Plan 3: How are Equality and Equity Different?

- ↑ Dressel, Paula (2014). "Racial Equality or Racial Equity? The Difference it Makes". Race Matters Institute.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 PeerNetBC (n.d.). Different Forms of Power [Handout].

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Justice." (2008). In W. A. Darity, Jr. (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2 (4), 114-116. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Tsosie, Rebecca (2012). "Indigenous Peoples and Epistemic Injustice: Science, Ethics, and Human Rights". Washington Law Review. 87 (4): 1133–1201.

- ↑ Parikh, Kirit. "Food Security." Encyclopedia of India, edited by Stanley Wolpert, vol. 2, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2006, pp. 93-96. Gale eBooks.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Patel, Raj (2009). "Food sovereignty". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 36 (3): 663–706. doi:10.1080/03066150903143079.

- ↑ Yankini, Malik (2014). “Food, Race, and Justice.” TEDx Talks.

- ↑ Sbicca, Joshua (2012). "Growing food justice by planting an anti-oppression foundation: opportunities and obstacles for a budding social movement". Agriculture and Human Values. 29: 455–466. doi:10.1007/s10460-012-9363-0.

- ↑ "Leaders of Color Discuss Structural Racism and White Privilege in the Food System". Civil Eats. 2016.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Alkon, Alison; Agyeman, Julian (2011). Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ↑ Alkon, Alison (2018). "Looking back to look forward". The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability. 23 (11): 1090–1093. doi:10.1080/13549839.2018.1534092.

- ↑ La Via Campesina (2007). "Declaration Of Nyeleni."

- ↑ Heynen, Nik; Kurtz, Hilda E.; Trauger, Amy (2012). "Food Justice, Hunger and the City". Geography Compass. 6 (5): 304–311. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00486.x.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Holt-Giménez, Eric (2010). "Food Security, Food Justice, or Food Sovereignty?" (PDF). Food First Backgrounder. Food First/ Institute for Food and Development Policy. 16 (4).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Allyship and Anti-Oppression: A Resource Guide: Definitions." TriCollege Libraries.

- ↑ "Privilege." Racial Equity Tools.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 "Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex". Indigenous Action Media. 2014.

- ↑ Sheridan, Robyn Stout (2017). "PEDAGOGY OF ACCOMPLICE: NAVIGATING COMPLICITY IN PEDAGOGIES AIMED TOWARD SOCIAL JUSTICE". Dissertations (1386).

- ↑ Sbicca, Joshua (2015). "Solidarity and Sweat Equity: For Reciprocal Food Justice Research". Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 5 (4): 63–67. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.004.

- ↑ "Ally." Racial Equity Tools.

- ↑ Dressel, Paula (2014). "Racial Equality or Racial Equity? The Difference it Makes". Race Matters Institute.

- ↑ Glennie, Charlotte; Alkon, Alison (2018). "Food justice: cultivating the field". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (7). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aac4b2.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2020). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, FAO.

- ↑ "What is Food Sovereignty". Food Secure Canada. 2013.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "What is the Food System?". Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Terms to Know". Center for Civic Education.

- ↑ Kidd, Ian James; Medina, José; Pohlhaus, Jr., Gaile (2017). The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315212043. ISBN 9781315212043.

- ↑ Koggel, Christine M. (2018). "Epistemic injustice in a settler nation: Canada's history of erasing, silencing, marginalizing". Journal of Global Ethics. 14 (2): 240–251. doi:10.1080/17449626.2018.1506996.

- ↑ Misawa, Mitsunori (2010). "Queer Race Pedagogy for Educators in Higher Education: Dealing with Power Dynamics and Positionality of LGBTQ Students of Color". The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy. 3 (1): 26–35.

- ↑ "Terminologies of oppression". The Anti-oppression Network.

- ↑ Sensoy, Ozlem; DiAngelo, Robin (2017). Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education (2 ed.). Teachers College Press.

- ↑ "Anti-Oppression". Simmons University Library.

- ↑ "What is Anti-Oppression?". The Anti-Oppression Network.