Indigenous seal hunting in northern Canada

Overview

Seals are a group of marine mammals commonly found in northern Canada.[1] Harp, hooded, grey, ringed, bearded and harbour are the six seal species that live on the Atlantic coast of Canada.[1] Indigenous seal hunting is a vital aspect of the traditional culture and way of life in northern Canada.[2] For thousands of years, Indigenous communities have relied on seal hunting for sustenance, clothing, tools, and trade.[3] In addition to providing essential resources such as food, oil, and skins for clothing and crafts, it also plays an important role in maintaining cultural traditions and passing on Indigenous knowledge to future generations.[4] This practice has deep cultural and spiritual significance, as well as an important role in preserving ecosystems and maintaining a balance between human populations and their natural environment.[4]

Traditional Indigenous seal hunting practices are deeply rooted in ecological knowledge, sustainable management, and respect for the environment.[5] Modern hunting methods have evolved beyond the traditional approaches to sealing, often resulting in inhumane deaths.[6] As a result, seal hunting is often characterized as a nefarious activity that seeks only to gain monetary profit through the elimination of the seal population.[7] The rise of seal poachers and their approach to sealing has attracted the attention of animal rights activists, including large organizations such as the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).[5] The broad imposition of these inhumane hunting methods upon all seal hunters regardless of heritage has introduced anti-sealing campaigns and international regulations that have targeted commercial sealing practices.[8]

Many misconceptions about the sustainability of Indigenous hunting and how it differentiates from commercial hunting have arisen from anti-sealing campaigns and regulations.[7] Inuit groups have begun to voice their concerns about their economy and livelihoods as a major Indigenous group in Canada.[9] Legislation is currently being developed to respect Inuit livelihoods while also working to manage poachers.[9] International markets are also beginning to play a larger part in the sealing economy.[10]

It is essential to recognize and respect the rights, knowledge, and sustainable practices of Indigenous peoples when addressing the complex issues surrounding seal hunting. Developing a deeper understanding of Indigenous seal hunting in northern Canada will contribute to more informed discussions, policies, and actions that support the continuation of this vital cultural practice for the well-being of these communities and the environment.

History of Indigenous seal hunting

For countless years, the Inuit have engaged in the hunting of bearded seal, harp seal, ringed seal, and harbor seal.[2] Ringed seals are the most typically sold to markets.[10] Seals are an important and culturally significant food source for the Inuit; other nutrition alternatives are sometimes costly, limited, and nutritionally insufficient.[10] Because Inuit do not require a license to hunt seals year-round,[11] no records exist to offer information on the number of hunters engaging in the fishery and the number of seals taken. However, it is believed that 6000 people work year-round in seal hunting in Nunavut alone. An estimated 30 000 ringed seals are taken each year from a population estimated to be between 1.5 and 3 million.[6]

Geographic distribution

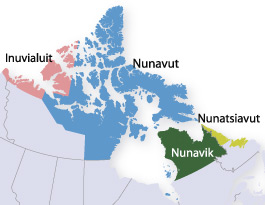

Canadian Inuit dwell throughout the Canadian North, from the Mackenzie Delta region near the Alaska border to Baffin Island and farther south in Quebec and Labrador.[12] The specific places where indigenous seal hunting occurs in northern Canada include Inuvialuit, Nunavut, Nunavik, and Nunatsiavut, which are also the places where Inuit are found.[10] Many Inuit tribes in Canada maintained a semi-nomadic existence focused on seal and caribou hunting until the mid-twentieth century.[12]

Hunting market

The Inuit historically started contributing to the Canadian economy by trading with and selling to the Hudson's Bay Company.[2] Nowadays, the Inuit earn money by selling sealskins to provincial and territorial governments.[10] The pelts are subsequently transported by government authorities to a designated fur auction, which is attended by both foreign and domestic purchasers.[10]Inuit frequently sell their pelts to auction houses.[10]

Hunting methods

Inuit peoples hunt seals by traveling to sea ice by snowmobiles, dog-sled teams, or small boats. They watch for hauled-out seals on the ice, wait at seal breathing holes, or seek for seals swimming. Using a rifle or shotgun, they will shoot the seal. More conventional equipment, like a harpoon, is occasionally employed.[13] Afterwards, the seal is processed and used to make traditional garments and cuisine. A man's classic parka is made from three to four sealskins.[2] More methods for mass industrial slaughter include the use of boats, helicopters, and hakapiks are generally used by non-Indigenous commercial sealers.[5]

Cultural significance

Indigenous livelihood

In both colonial and Indigenous communities in Atlantic Canada, the hunts have a substantial economic and cultural impact,[3] and seal hunting is a traditional act of patience, labor, and care.[4] Seals are hunted for their meat, oil, and fur (for clothing). The meat of the seal is eaten, and the food is considered a primary source of energy.[4] The animal oils are burned for fuel, to treat pelts, and also for monetary profit in the seal market.[4] The diminishing market for seal is one of the sole sources of income that Indigenous peoples in northern Canada depend on.[4]

Seal meat itself has the texture of beef and a fishy flavor, despite being very healthy as well as rich in protein and iron.[3] As a result, there is a restricted market for seal meat, and several Canadian restaurants have recently started to include the seal on their menus.[3] Moreover, some businesses have begun using seal meat in animal feed. Seal oil is utilized in nutritional supplements and other items (e.g., shoe polish). Seal fur, however, is the primary factor in commercial sealing and is used in high-end fashion designs all over the world.[3]

Ties to Indigenous identity and spirituality

Many indigenous ideologies view humans and animals as related through indissoluble relationships.[14] Seal hunting itself is deeply intertwined with Indigenous identity and spirituality. It is seen as a sacred practice, with rituals and ceremonies associated with the hunt. [15]The act of hunting and the use of all parts of the animal also reflects Indigenous values of sustainability and respect for the land and its resources.[15] Seal hunting is also an important way for Indigenous communities to assert their sovereignty and maintain their connections to the land and their traditional ways of life.[15] Most of the nuance and traditional procedures were lost in anti-seal media campaigns, which often depict seals as victims and sealers as villains.[7]

Controversies

In Canada, there is a distinction between the commercial and the Indigenous seal hunt. The commercial seal hunt in northern Canada has long been a contentious issue, with animal rights activists raising concerns about the animal suffering involved in seal hunting tactics.[5] However, Indigenous seal hunters largely depend on the commercial hunt for the economic viability of their livelihoods, so legislation about the commercial hunt may impact Indigenous cultural, nutritional, and economic practices.[5][9] Both hunts are also included in a wider debate about the inherent morality of sealing.[16] Government legislation, international regulations like the European Union's seal product prohibition, and Indigenous interests complicate this issue. In this section, we will examine varying perspectives, the EU prohibition on seal products, and proposed solutions or compromises to these conflicts.

Animal welfare and conservation concerns

Certain animal welfare and environmental advocacy groups have campaigned against seal hunting, including the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (SSCS), Humane Society International (HSI), People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), and Greenpeace.[5][3] These organizations are especially concerned about the use of rifles and hakapiks, which they feel, if not used appropriately, can result in a slow and agonizing death for seals. They support more stringent laws and oversight to guarantee that seals are dispatched swiftly and humanely.

Anti-sealing campaigners argue that commercial sealing is unnecessarily cruel and wasteful. British veterinary science researcher Andy Butterworth, who has observed the commercial hunt, states that seals are often butchered inhumanely, with methods including clubbing to death and shooting, and some seals are simply killed and then lost in the depths of the sea.[8] 40% of seals that were shot required further clubbing to render them unconscious.[16] In 1997, a seal-hunting cap was imposed in Canada, setting the limit at 275,000 seals per year until 1999.[17] However, this was concluded by Johnston et al. to be unlikely to sustain the seal population, and the cap itself was often overshot.[17]

Animal justice advocates argue that Indigenous hunting is less harmful to the environment than other types of commercial hunting. In mass industrial hunting, for instance, “an estimated 92 percent of seal meat goes to waste due to a lack of demand.”[5] According to this evaluation of different types of sealing, some NGOs and animal advocacy groups advocate for an end to seal hunting except for Indigenous seal hunting. This line of argument creates controversy where Indigenous and commercial hunting overlap.

In addition to animal welfare concerns, conservationists worry about the long-term sustainability of seal populations. Although the Canadian government maintains that seal hunting is carried out sustainably and that quotas are established based on scientific research, some critics argue that climate change, habitat loss, and other human activities may pose a threat to the seal populations in the future.[5] These concerns have led to calls for more comprehensive population monitoring and adaptive management strategies that consider the potential impacts of climate change on the Arctic ecosystem.

It is essential to note that many Indigenous communities have practiced seal hunting for generations, with a deep understanding and respect for the animals and their environment. Indigenous hunters often adhere to traditional practices and beliefs that promote the sustainable and humane treatment of seals. For these communities, seal hunting is not only a vital source of nutrition and income but also an essential aspect of their cultural identity. [2]

Possible solutions to the issues of animal welfare and conservation include the creation and application of stricter rules and regulations and guidelines for hunting practices, increased transparency in population monitoring, and collaboration between Indigenous communities, governments, and conservation organizations to promote sustainable and humane hunting practices. [16]

Legal and political issues

The harvest of seals is highly governed, supervised, and enforced. The Canadian government is dedicated to ensuring that seals are harvested in a humane, safe manner and compliance with the guidelines outlined in the Marine Mammal Regulations (MMR). Canada's Department of Fisheries and Oceans recognizes Indigenous sealers' right to hunt seals without licenses or maximum catches.[5]

In 2009, the European Union (EU) adopted a ban on trade in seal products, with an exemption for Indigenous-hunted products.[18][19] This ban was developed according to a certain European moral standard and not specific environmental or economic concerns.[19]

The European Union (EU) prohibition makes it clear that seal products may only be sold in areas where they were obtained via traditional Inuit and other Indigenous groups' hunting practices and where necessary for their sustenance.[20] Despite the exception, Indigenous people have spoken out against the ban, arguing that with the dissolution of a commercial market for seal products, they become unable to sell seal goods in a manner capable of supporting themselves.[21] Pelt costs have decreased by 64% from 2007 levels ever since the legislation was proposed.[21] The Inuit have argued that the legislation harms customary economic activity and that the authorities have not evaluated the interests of Inuit communities against particular moral beliefs.[22] Indigenous peoples' opinions were not believed to have been effectively heard in the decision-making process, and according to them, the legislation does not represent the reality of the Inuit commercial harvest, which is both compassionate and important for the ongoing existence of these tribes.[21]

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was approved by the UN General Assembly in 2007, represents a normative advancement. The statement outlined a variety of cultural, religious, traditional, spiritual, and linguistic rights relating to Indigenous peoples' spiritual traditions, histories, and philosophies, particularly about their native lands, territories, and resources.[23] The contribution of Indigenous knowledge and traditional ways of life to sustainable, fair development and good environmental management is well known. The Rio Declaration, which was approved in 1992, also acknowledges this reality. Because of their knowledge and customs, indigenous people, their communities, and other local groups, according to Principle 22, play a crucial part in environmental management and development. [24]

Miscellaneous media and events

In 2014, the American celebrity Ellen DeGeneres posted an anti-sealing Tweet to her millions of followers to fundraise for the Humane Society of the United States, sparking backlash from seal hunt supporters, heated debate between animal rights activists and supporters of the hunt, and some confusion between the Indigenous and commercial hunts among Twitter users.[3] A significant consequence of this tweet was the proliferation of the hashtag #sealfie (a play on “selfie”) among Inuits who tweeted photos of themselves next to dead seals and seal products to showcase their pride in their way of life.[3]

Althethea Arnaquq-Baril is the creator of the film titled Angry Inuk, which was created in 2016 for Westerners in order to Inuits' anguish over the threats to seal hunting.[9] Angry Inuk is a documentary about the Inuits’ fight to repeal bans against seal products and their trading.[9] Bans on seal products may plunge Inuits even deeper into poverty, despite them being the poorest Indigenous group in North America, as well as having the highest levels of food insecurity. Even in the face of these devastating effects on the Inuit, Inuit peoples are often excluded from the discussion and subsequently subjected to hatred from animal rights activists.

The debate over the ethics of seal hunting is constantly shifting. In 2009, the company Lush Cosmetics campaigned in order to raise money to stop seal hunting and revoke federal support, while protest from Inuit went largely unnoticed.[9] However, during a repeat campaign in 2018, there was significant backlash from Inuit allies who may have been inspired by the film Angry Inuk, indicating that Canadians have become more sensitive to the poverty and food insecurity levels of the Indigenous party.[9]

Misunderstandings, misrepresentations, and stereotypes

In part due to the controversy around the commercial seal hunt in northern Canada, Indigenous seal hunting is often included in a debate about the morality of seal hunting, and it may be attacked as inhumane or misrepresented as unsustainable.

In the #sealfie debates over seal hunting that took place on Twitter in 2014, volatile interactions often took place between Indigenous rights and animal rights activists in which Indigenous people were negatively stereotyped.[3] In debates such as these, where ethics of the visible treatment of animals clash,[16] it is common for Indigenous groups to be characterized as “savage” by some debaters.[5]

In addition to inaccuracy in informal discourse, institutions such as government agencies and animal rights organizations have been known to misrepresent Indigenous sealing. One of the most widespread worries is that government regulators stigmatize hunters by portraying Indigenous hunting as having a negative effect on marine animal populations,[14] when the actual hunt consists of an average of 1,500-2,000 seals[5] annually and has no detrimental impact to the ecosystem.

Future of Indigenous seal hunting

After the 2009 European Union (EU) ban, the Inuit claimed that the prohibition had decimated their villages.[10] The government organized "Seal Day on The Hill" in May 2016 to raise awareness of seal goods and to demonstrate its support. The same day, Inuit seal products were to be developed and marketed thanks to a $5 million budget, according to Fisheries Minister Hunter Tootoo.[25] The "Certification and Market Access Program for Seals" was the name given to this fund (CMAPS). National Seal Products Day was established by the government to once again commemorate the significance of the seal hunt for Canada's "Indigenous people, coastal towns, and overall population."[10] Due to the need to comply with the EU exemption and provide consumers with trust, the current CMAPS plan is attempting to address the sealskin trade on a global scale.[10] To ensure that items are "Inuit-harvested," authorized certification organizations are formed through CMAPS in Canada so that the EU would accept them. Canada now recognizes just two certification organizations: the governments of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. As previously, the Inuit sell their seal skins to government officials who verify that they were captured by the Inuit.[10]

Challenges

CMAPS program uncertainty

Although the CMAPS plan has given the Inuit marketing infrastructure, it is unknown how much it has helped the Inuit or whether other Arctic areas are attempting to be recognized as certifying authorities.[10] Trade information from this program is currently being gathered and is not yet available to the general public.[10] Between 2004 and 2016, overall seal exports were still declining.[10] So, it is probable that more money than the 5.7 million will be needed to resuscitate and maintain the Atlantic sealing business as well as Inuit-harvested seal goods.[10]

Food insecurity

Expecting the ecology and subsistence economy to supply the food demands of an expanding Inuit population is unrealistic.[26] Because Inuit increasingly reside in permanent communities and hunt more intensely in neighboring regions, there are concerns about the environmental limits of sustenance species.[26] The warming Arctic also has an impact on the accessibility, availability, and abundance of traditionally gathered foods. Most Inuit rely on imported foods, which are often low in nutrients and costly to obtain.[26] This transition from a subsistence-based diet based primarily on country foods (particularly fish, seals, and whales) to a diet based primarily on store-bought foods (poor nutritional content and no cultural resonance) has been noted as a critical concern for food security.[26] According to current research on Arctic food security, possibilities to assist Inuit food security must be generated by communities, with participation from regional and national stakeholders, therefore contributing to food sovereignty.[26]

Climate change

Climate change is already evident in the Canadian Arctic.[27] For example, the weather has grown unpredictable, and elders' forecasts are no longer accurate. Prediction, on the other hand, is vital for anticipating hunting threats. Unpredictable weather and abrupt weather changes have prompted hunters to spend extra nights on the ground waiting for calm conditions. [27]More unexpected weather (rain in the winter, harsh cold in the spring) endangers hunters. Wind strength and direction changes that are sudden, along with stronger winds Access to summer hunting regions by boat is restricted. [27]Sea ice is less stable and more likely to break up unexpectedly, resulting in slower freeze-up and early break-up, increasing the risk of moving on sea and lake ice. More snow on the ice if it falls might conceal thin ice, increasing the number of hunters who fall through hidden thin ice. [27]These changes pose threats and hazards to Inuit villages in Canada's Nunavut area, and locals are increasingly concerned. [27]

Potential Opportunities

Cultural preservation

Many Indigenous communities are taking steps to promote sustainable hunting practices and preserve their cultural traditions. This includes implementing traditional ecological knowledge into management plans, working with scientists and conservation organizations, and educating the public about the importance of traditional hunting practices.[15] The Canadian government has also provided funding for these efforts, recognizing the importance of Indigenous cultural practices and the need for sustainable management of resources. [28] In addition, organizations such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Arctic Council have worked to promote international recognition of Indigenous rights to traditional hunting practices and the importance of sustainable management of marine resources. [29]

Atlantic market

The CMAPS program strives to improve market access for commercially harvested Atlantic seal products in addition to supporting initiatives that support Inuit-harvested seal goods.[30] China and other Asian countries seem to be growing markets for seal goods right now.[10] Demand for Inuit-harvested sealskins is likely to increase if the market for Atlantic seal items in Asian countries keeps growing.[10]

Contribute to adaptation strategy

Inuit populations in Canada are facing significant challenges due to climate change.[31] Fortunately, Indigenous peoples have a long history of adjusting to changes in society and the environment, and their collective knowledge and wisdom may help us comprehend and adapt to the changes caused by climate change.[31] Traditional ecological knowledge is critical in enabling flexibility and creativity in hunting, danger avoidance, and emergency preparedness, especially in changing climatic circumstances.[31] Inuit prosperity in the Arctic has long been connected with their capacity to be adaptable and imaginative in their utilization of the environment and resources.[31] Inuit deal with unpredictability; they alter their seasonal cycles to hunt what is available when it is available, and they rely on acquired experiences, oral traditions, and communal memory of prior situations to respond to environmental changes and severe occurrences.[31] Several studies and significant international climate change assessments have underlined the relevance of traditional ecological knowledge in adaptation; yet, its significance is not recognized in the majority of adaptation policy procedures, which means more exploration is needed. [31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Identify a species". Identify a species. March 23 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Peter, A., Ishulutak, M., Shaimaiyuk, J., Shaimaiyuk, J., Kisa, N., Kootoo, B., & Enuaraq, S. (2002). The seal: An integral part of our culture. Études/Inuit/Studies, 167-174.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Knezevic, I., Pasho, J., & Dobson, K. (2018). Seal hunts in canada and on twitter: Exploring the tensions between indigenous rights and animal rights with #Sealfie. Canadian Journal of Communication, 43(3), 421-439. doi:https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2017v43n3a3376

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Freeburg, Sage (2022). "Animal Oil, Animal Blood: Energy, Metabolism, and Protecting the Seal Hunt in the North American Arctic as an Act of Colonial Resistance". Media+Environment. 4.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Person, Darren, & Chang. (2020, March 2). Tensions in contemporary indigenous and animal advocacy struggles: 2. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003013891-2/tensions-contemporary-indigenous-animal-advocacy-struggles-darren-chang

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Government of Nunavut. (2012). Report on the impacts of the European Union Seal Ban, (EC) NO 1007/2009, in Nunavut. Iqaluit: Department of Environment. https://www.gov. nu.ca/environment/documents/reportimpacts-european-union-seal-ban-ec-no-10072009nunavut-2012

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Farquhar, Samantha (March 2020). "Inuit Seal Hunting in Canada: Emerging Narratives in an Old Controversy". Arctic. 73 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Butterworth, Andrew (2014). "The moral problem with commercial seal hunting: The canadian seal hunt leads to animal suffering, and a european union ban on the import of its products should stand, says andy butterworth". Nature (London). 509 (7498): 9.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 "Life with the seal: Angry Inuk exposes the complexities and damage that seal hunt bans have inflicted upon northern communities". Alternatives Journal (Waterloo). 44 (1): 54. 2019 – via EBSCO.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 Farquhar, S. D. (2020). Inuit seal hunting in canada: Emerging narratives in an old controversy. Arctic, 73(1), 13-19. doi:https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic69833

- ↑ Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2011). 2011 - 2015 integrated fisheries management plan for Atlantic seals. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/seals-phoques/ reports-rapports/mgtplan-planges20112015/mgtplanplanges20112015-eng.html#c1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nuttall, Mark (2019). Indigenous peoples, self-determination and the Arctic environment. The Arctic. p. 382. ISBN 9780429340475.

- ↑ Pelly, D. F., & Franks, C. E. S. (2002). Sacred hunt: A portrait of the relationship between seals and Inuit. The American Review of Canadian Studies, 32(4), 723.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Coté, C. (2016). “Indigenizing” food sovereignty. Revitalizing indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities, 5(3), 57.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Nadasdy, P. (2003). Hunters and Bureaucrats: Power, Knowledge, and Aboriginal-State Relations in the Southwest Yukon. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Butterworth, A., & Richardson, M. (2013). A review of animal welfare implications of the canadian commercial seal hunt. Marine Policy, 38, 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.07.006 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":20" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 17.0 17.1 Johnston, D. W; Meisenheimer, P.; Lavigne, D. M (June 2000). "An Evaluation of Management Objectives for Canada's Commercial Harp Seal Hunt, 1996-1998". Conservation Biology. 14: 729–737 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Cambou, Dorothée (01 Jan 2013). "The Impact of the Ban on Seal Products on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: A European Issue". The Yearbook of Polar Law Online. 5: 389–415 – via Brill. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sellheim, Nikolas (Jan 8 2016). "The Legal Question of Morality: Seal Hunting and the European Moral Standard". Social & Legal Studies. 25 – via SAGE Journals. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ European Community. (2009). Regulation (EC) No. 1007/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, L 286/36, 16 September 2009. Official Journall L 286/3.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hossain, K. (2013). The EU ban on the import of seal products and the WTO regulations: Neglected human rights of the Arctic indigenous peoples? Polar Record, 49(2), 154-166. doi:10.1017/S0032247412000174

- ↑ Koivurova, T., Kokko, K., Duyck, S., Sellheim, N., & Stepien, A. (2012). The present and future competence of the European Union in the Arctic. Polar record, 48(4), 361-371.

- ↑ United Nations General Assembly. (2007). The United Nations declaration on the rights of the indigenous peoples. New York: UN General Assembly Declaration.

- ↑ United Nations. (1992). The Rio declaration on environment and development. Rio De Janeiro.

- ↑ Government of Canada. (2016). Government of Canada marks "Seal Day on the Hill 2016." Ottawa: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs/ news/2016/05/government-of-canada-marks-seal-day-on-thehill-2016-.html

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Hoover, C., Ostertag, S., Hornby, C., Parker, C., Hansen-Craik, K., Loseto, L., & Pearce, T. (2016). The continued importance of hunting for future Inuit food security. Solutions, 7(4), 40-50.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Ford, J. D., Smit, B., Wandel, J., Allurut, M., Shappa, K., Ittusarjuat, H., & Qrunnut, K. (2008). Climate change in the Arctic: current and future vulnerability in two Inuit communities in Canada. Geographical Journal, 174(1), 45-62.

- ↑ Nadasdy, P. (2017). Sovereignty and survival: Indigenous encounters with neoliberalism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Ljubicic, G. (2010). Seals, seal hunting and the Inuit: Continuity and change. Polar Record, 46(238), 77-86. doi: 10.1017/S0032247409990205

- ↑ Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2017). Certification and market access program for seals. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/seals-phoques/ certification-eng.html

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Pearce, T., Ford, J., Willox, A. C., & Smit, B. (2015). Inuit traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), subsistence hunting and adaptation to climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic, 233-245.