Indigenous Representation in Hollywood

History and Portrayal in Hollywood

Classic Hollywood

Classic Hollywood contained many controversial portrayals of Native people in film. Often portrayed as the savage antagonist, Native people were vilified to an entire generation of consumers. Nearing the end of the classic Hollywood era people became less vocal about Native prejudice, but it still was apparent through the treatment of the characters portrayed, with many films featuring redfaced white actors to fill Native roles.[1]

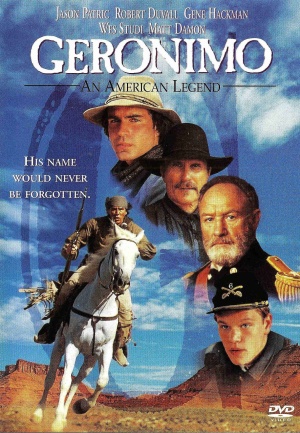

Revisionist Films

In the post-classical Hollywood era emerged films that made the claim to be more sympathetic to Native people. These films, coined as revisionist, focused on the individualizing of Native people, sympathizing rather than vilifying them. Cooperation of white settlers and Natives were shown more liberally, as well as redirecting the blame for colonial violence so as it did not fall solely on the “savage nature” of Native people. Blame for the atrocities committed against Native people is shifted in revisionist films as well. Rather than accurately pointing to a prejudiced system of oppression, the atrocities are often portrayed as being perpetuated by a villainous few, exonerating western society from their actions. To cement this exoneration white characters, sympathetic to the plights of Native people are often used to balance out the villainous ones. [2]

Redface

Many films in early Hollywood often used white actors to portray Native due to a deep seated racism within the institution of film. Natives were not the only race to be whitewashed, and despite marginal improvement are still whitewashed in some films today. The Hollywoodization effect of redface has seen that even Native actors are sometimes subjected to the darkening of their skin to fit a “realistic” depiction.[1][2]

Hollywood Tropes

White Savior

The Hollywood trope of marginalized people being uplifted by a singular white character is a common phenomena in revisionist films. This trope is problematic in that it shows that the marginalized individuals are not capable of change on their own, but need to be helped by a white benefactor. This ingrains the idea that minorities are not capable of helping themselves, and need western intervention to break free of their social, economic, and political predicaments. This trope also fails to address the causes of issues facing minority groups, which are often rooted in eurocentric western society, giving the false impression that the minority groups are being saved from themselves rather than a larger system of oppression. In a whole the “ white savior” trope suggests that change is best sought through white leadership and that people of minorities are incapable of such feats and are complacent to their social predicaments. [3]

Noble Savage

The “noble savage” stems from the romanticizing of the incorruptible Native individual, revered for their connection to the natural world and viewed as innocent and pure. This trope demotes the capabilities of indigenous peoples, painting them as naive with a lack of self determination resulting from their primitive ways. [3]

Viewership and Effects on the Native Populace

The effects of Native misrepresentation in Hollywood are a very real detriment to Native people. The demographic of American moviegoers is predominantly white, as the majority Hollywood films are often tailored to this audience, being the majority in America. Consumers are subjected to Hollywood’s dictation of the Native image, which in turn becomes public opinion that reflects on actual Native people. [3]

This stilted demographic targeting also leads to under representation of Native people in film and television, with only 0.3% of filmic presences being Native, compared to the 2% that makes up the population. This lack of representation, combined with the misrepresentation of most instances that Native people do appear leaves very little for Native audiences to identify with. [1]

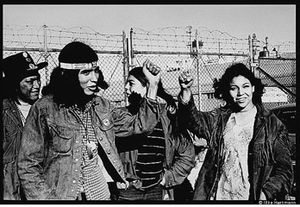

Native Cinema

Although Native cinema is not new, there has been a recent influx of indigenous artists making work to reclaim their own culture and narrative, as well as attention by those outside of Native communities acknowledging their work. Native filmmakers are gaining their own voice within the film community, creating works that subvert Hollywood’s imposed narrative and bring attention to issues such as colonization, residential schools, and the continued marginalization of Native people still faced today. [4]

One of the biggest restrictions on native filmmakers is the “niche market” in which their work usually falls. Due to commercial, political, and narrative structures in Hollywood cinema most Native filmmakers find themselves working in the realm of low budget film and documentary. Cinema of other countries such as New Zealand, Australia and Canada are more open to native filmmakers but due to the hegemonic monopoly on film distribution by Hollywood even these national film board endorsed films reach only a small audience. [5]

One example of Native film reaching a larger audience is First Nations/ First Features: A showcase of world indigenous film and media, a 2005 collaboration between the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. This festival ran for 12 days, featuring screenings of the first feature films by indigenous filmmakers, appropriating western technology to showcase their work traditionally oppressive medium used to find a voice. [5]

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Van Alst Jr. Theodore C. (2015) Ridiculous Flix: Buckskin, Boycotts, and Busted Hollywood Narratives, Great Plains Quarterly, Volume 35, Number 4, Fall 2015, pp. 321-331

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Bungert, H (2005) “Two Times ‘Geronimo’” Changes in Representation of Native American History in Film

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cammarota, J (2011) Blindsided by the Avatar: White Saviors and Allies Out of Hollywood and in Education, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33:3, pp. 242-259 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2011.585287

- ↑ Gauthier, J. L. (2015), ‘Embodying change: Cinematic representations of Indigenous women’s bodies, a cross-cultural comparison’, International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 11: 3, pp. 283–298,

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gauthier, J. L. (2004) Indigenous Feature Films: A New Hope for National Cinemas? Cineaction; International Index to Performing Arts, pg. 63