Grsj224/neoliberalismandincomeinequality

Income inequality, the extent to which income is distributed in an uneven manner among a population, has become widespread and a persistent issue globally. Many people blame economic globalization to be the cause of rising income inequality. Arguably, many people in developing countries have been lifted out of poverty through economic globalization. But because of this, many workers have also been displaced out of jobs in the developed world. There are many other factors that are considered to exacerbate income disparity, but the rise of neoliberalism has been the underlying cause of an ever-increasing income inequality.[1]

Neoliberalism and Income Inequality

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism refers to the ideology and policy model that emphasizes the greater role of the free market over the state in economic planning.[2] It has been the dominant economic ideology since the 1980s. It emphasizes that free markets, meaning minimal intervention by government or state in economic and social affairs, will lead to an efficient allocation of resources and sustained economic growth in society.

The economist Milton Friedman spurred much of the intellectual inspiration on Neoliberalism. He argues that the “free private enterprise exchange economy” i.e. capitalism, is the only system which provides individuals with economic freedom.[3] A freedom to trade and form contracts with others without outside intervention, meaning without coercion. Friedman’s ideologies do not consider the threat of starvation and homelessness for not working or being left out in a competitive society to be a form of coercion. He also believes that the one and only social responsibility of business was to maximise stockholder value, in terms of profits, growth or dividends.[4] With this ideology, the role of government is very limited and only has to do with functions that are necessary to preserve greater freedom which attracted many followers in the next following decades.

The Rise of Neoliberalism

Before the rise of neoliberalism, there was a dominant Keynesian economic orientation. This system of principles, norms and decision-making policies in the political economy was called Keynesianism. It was named after the British economist John Maynard Keynes. The Keynesian economic orientation advocates for state interventions to dampen business cycle, ensure continuous economic growth, and keep employment high.[5] With Keynesianism, the state is expected to intervene when there is an economic slowdown. One way is to build more infrastructure to provide more jobs.

During the 1970’s, global economic growth started to slow while inflation and employment were on the rise. From 1973 to 1975, there was also a major global recession. Additionally, the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 led oil prices to spike. As a result, these made economic growth even harder. On top of these events, there was a general Third World debt crisis where international debt grew exponentially. Much of Latin America and the Third world were not able to repay their initial loans. Payments for these loans had to be restructured which led to privatization of state-owned enterprises, fiscal austerity, deregulation of businesses, regressive taxation, and trade and investment openness.[6] These crises that have caused economic stagnation made decision-making elites question the old ways of doing things which paved the way for change.

Many think tank, lobbying groups, and economic organizations started to shift and abandoned their Keynesian economic orientation. Also, many countries underwent a shift in national politics which embraced a greater role for the free market in the economy and less of the Keynesian economic principles. This led to social welfare policies becoming under attack, subjected to declining funds, or outright dismantlement. Additionally, pressure to privatize government production grew like in housing, education, utilities, and media (Harvey, 2005). This paved the way for the transfer of control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector by promoting policy transformations such as privatization, open trade, deregulation of business and finance, public spending cuts, lower taxation especially of corporations and the wealthy – in short, neoliberalist policies.[6]

The Federal Reserve (US Central bank; Fed in short) also adapted a new system of monetarism which was aimed at counteracting inflation through the control of interest rates. A new role of the Fed was to keep employment relatively low because high employment keeps the supply of workers tight. When the supply of workers is tight, it pressures employers to raise wages which puts upward pressure on inflation rates. By raising interest rates, the Fed can control and slow economic growth to tame inflation rates.[7] Because of this, the Fed clearly had no interest in full employment, livable wages or to even maximize economic growth. The Fed’s new orientation was to help raise private profits. Moreover, the Feds became lenient towards finance. Because deregulation was promoted, this led to some parts of the economy transforming into a speculative financial economy from a productive manufacturing one. Financial markets soon dominated traditional productive markets like manufacturing, service, and agriculture.

These events that pushed for a change to neoliberalist policies and orientation would help accumulate profits that benefitted the wealthy and privileged. As a result, neoliberalism has caused a disproportionate income inequality between the rich and the rest of the people.

Introduction to Income Inequality

Income inequality refers to the extent to which income is distributed in an uneven manner among a population. Intuitively, income inequality refers to the fact that different people earn different amounts of money.[8] The wider those earnings are dispersed, the more unequal they are. The most striking aspect has been the widening gap between the rich and the rest.

To put this into perspective, in 2015, Canada’s top 10 per cent earners had total incomes that were 2.74 times those of the median person. And the top 1 per cent had a pre-tax income of $234,130 which is at least 6.8 times higher than the median.[9] Also, a study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental economic organisation with 36 member countries to stimulate economic progress and world trade, shows that a quarter of a century ago, the average disposable income of the richest 10% in OECD countries was around seven times higher than that of the poorest 10%; today, it’s around 9½ times higher.[10] And in 2017, the wealthiest 1 percent of the world's population now owns more than half of the world's wealth.[11]

How is income inequality measured?

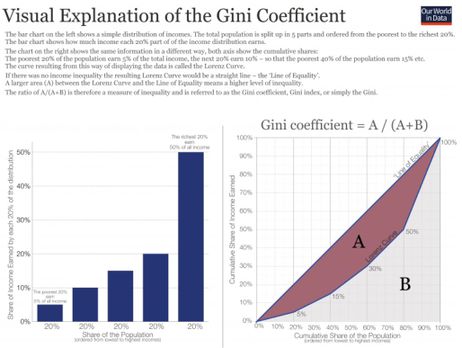

The Gini coefficient is a number that quantifies the extent of income inequality in a country. It is the most widely used single-summary number for judging the level of inequality in a particular country or region.[8] However, it is important to know that the Gini coefficient provides only a high-level overview and may miss the increasing share of income going to the top 1% or 10% of earners.

How is the Gini coefficient derived?

To derive a Gini coefficient, one can start with a Lorenz curve. In a Lorenz curve, the horizontal axis on the chart represents cumulative shares of the population. The vertical axis is cumulative shares of income. The graph below explains how it works and how the numbers are derived.

Effects of Income Inequality

Some economists believe that some income inequality is efficient or good for the economy. In his 1975 work "Equality and Efficient: The Big Trade-Off," the Harvard economist Arthur Okun argued that inequality was the price to be paid for an efficient economy which became the backbone of conservative policy.[12] He believed that income inequality is "a by-product of a functioning capitalist society" and the wealthiest had more, because they were more productive.[12]

But even economists worry that inequality inhibits growth and opportunity when it becomes too high, which is the case in many countries.[13] Widening income disparity, which can be witnessed in many countries, is alarming because it is known to adversely affect many aspects of well-being. The harmful effects of widening income inequality affect national health and education outcomes, as well as residential segregation.[14] Additionally, numerous of social factors such as social mobility, growing crime rates leading to increased rates of imprisonment, less healthy choices of food consumption leading to obesity, and life expectancy and mental health have strong correlation with levels of income inequality: the higher the inequality within a country, the higher the measured social ill.[15]

Additionally, income inequality where income growth accrues disproportionately to the top income groups stunts economic growth. This happens as more people fall into poverty because the middle class gets “hollowed out”. Since the middle class is the backbone of many economies, this results in lower aggregate demand in the economy as more people can’t afford to spend compared to a few that can. As a result, there may be a slowdown in productivity growth which has an adverse impact on resource allocations as well as on the incentive structure, innovation, and diffusion of technology.[16] Slower economic growth leads to the increasing importance of capital for financial prosperity. In turn, this leads to an “accelerating” wealth gap as those with capital can invest it for further asset growth, whereas those without cannot.[17]

Neoliberalism as the Underlying Cause of Income Inequality

Different reports claim different factors contribute to rising income inequality. One argument focuses on on market intervention by the state on issues involving social welfare, progressive taxation, and power of labour movements.[18] Atkinson argues that these mechanisms that have historically reduced income disparity by redistributing market income have been in decline for decades in many countries[18]. Another focus of inquiry, the “great U-turn”, has been blamed for its contribution to rising income inequality through corporate restructuring. It involves deindustrialization which entails the loss of the middle class throughout the developed world.[19]

Additionally, economic globalization, as a result of technological progress, has been greatly blamed as another cause on income inequality. Alderson & Nielsen argue that trade and investment typically favours the wealthier households[19]. Also, economic globalization has led to more open international trade and investment and the rise of powerful transnational corporations which have pressured countries to adopt market-oriented reforms.

Despite these factors, supported by empirical evidence, being valid arguments, focusing on these issues misses the big picture. Kotz argues that globalization is just an intermediary factor while neoliberalism is the deeper underlying cause of an ever-increasing income inequality.[20] Additionally, he argues that globalization is not just a result of technological progress because the technology for globalization has existed long before the 1970’s.

The consensus of corporate and decision-making elites without public participation in the 1970’s to shift from a Keynesian strategy of state intervention, domestic production, and public investment to a neoliberal strategy of economic liberalism, export-oriented growth, and privatization is the fundamental cause of rising inequality.

Neoliberalism is a multifaceted social and economic system with a multidimensional phenomenon. Many strategies were implemented to help revitalize profits and keep a high return of investment such as business, finance, and labour deregulation. Additionally, there were tax reforms, social spending cuts, privatization of publicly owned firms, monetarist policy that places inflation control above full employment, offshoring and downsizing, international free trade agreements, increasing foreign investment, and export-led growth.

Activism Against Income Inequality

Income inequality was largely ignored by leaders and policy makers around the world during much of its climb. Only after the Great Recession and Occupy Movement did the problem of growing income inequality finally capture mainstream attention.

The Occupy Movement was not simply a group of activists with complaints against corporate greed; it encompassed so much more. Greed, corporate influence, and income inequality were by-products of the main issue of the movement: the social and economic system influenced by neoliberalist policies.

“We are the 99%” is a political slogan widely used and coined by the Occupy movement. The phrase directly refers to the income and wealth inequality in the United States with a concentration of wealth among the top earning 1%.[21] It reflects an opinion that the "99%" are paying the price for the mistakes of a tiny minority within the upper class.[21]

The first Occupy protest to receive widespread attention was Occupy Wall Street (OWS). It began in New York City's Zuccotti Park on September 17, 2011. Occupy Wall Street, an anti-capitalist social movement, emerged in the United States in 2011 after a massive housing market collapse.[22] Their focus was to help change the economic and political landscape by raising awareness of income inequality, political corruption and the power of the rich.[22] The OWS movement can be seen as one of the most influential movements in recent US history. It brought on congressmen, politicians, and the general public to discuss the severity of social inequality in the United States.

Six years after OWS, income inequality is still on the rise. New figures from Oxfam show the world's billionaires increased their fortunes by a handsome $762-billion in just 12 months. And that 82 per cent of new wealth created last year went to the top 1 per cent. [23] The trend where the rich are getting richer at expense of everyone else still continues.

Sources

- ↑ Stone, J. (2016, May 27). Neoliberalism is increasing inequality and stunting economic growth, the IMF says. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/neoliberalism-is-increasing-inequality-and-stunting-economic-growth-the-imf-says-a7052416.html

- ↑ Coburn, D. (2000). Income inequality, social cohesion and the health status of populations: The role of neo-liberalism. Social Science & Medicine,] 51(1), 135-146. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00445-1

- ↑ Eagleton-Pierce, M. (2016). Neoliberalism: The key concepts. Abingdon, Oxon;New York, NY;: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203798188

- ↑ Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Friedman. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- ↑ Arnon, A., Weinblatt, J., Young, W., & SpringerLink ebooks - Business and Economics. (2010;2011;). Perspectives on keynesian economics (1st ed.). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14409-7

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wade, R. H. (2007). Ngaire Woods The Globalizers: The IMF, the World Bank and Their Borrowers. New Political Economy, 12(1), 127-138. doi:10.1080/13563460601068909

- ↑ Baker, D. (2006). Beyond the conservative nanny state: Policies to promote self-sufficiency among the wealthy.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Yglesias, M. (2014, April 02). What is income inequality? Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/cards/income-inequality/what-is-income-inequality

- ↑ Census data shows income inequality remains a major challenge. (2017, October 09). Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-commentary/census-shows-income-inequality-is-on-the-rise/article36524022/

- ↑ Keeley, B., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, & OECD iLibrary. (2015). Income inequality: The gap between rich and poor. Paris: OECD.

- ↑ Frank, R. (2017, November 14). Richest 1% now owns half the world's wealth. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/14/richest-1-percent-now-own-half-the-worlds-wealth.html

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ellyatt, H. (2013, January 08). Is Income Inequality as American as Apple Pie? Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/id/100361302

- ↑ Voinea, L., Lovin, H., & Cojocaru, A. (2018). The impact of inequality on the transmission of monetary policy. Journal of International Money and Finance, 85, 236-250. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.11.007

- ↑ Jencks, C. (2002). Does inequality matter? Daedalus, 131(1), 49-65.

- ↑ Schröder, M. (2016). Is Income Inequality Related to Tolerance for Inequality? Social Justice Research, 30(1), 23-47. doi:10.1007/s11211-016-0276-8

- ↑ Slottje, D. J., Raj, B., SpringerLINK eBooks - English/International Collection (Archive), & SpringerLink (Online service). (1999;1998;). Income inequality, poverty, and economic welfare. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-51073-1

- ↑ Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Belknap harvard.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Atkinson, A. B. (2003). Income inequality in OECD countries: Data and explanations. CESifo Economic Studies, 49(4), 479-513. doi:10.1093/cesifo/49.4.479

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Alderson, A. S., & Nielsen, F. (2002). Globalization and the great U-turn: Income inequality trends in 16 OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology, 107(5), 1244-1299. doi:10.1086/341329

- ↑ Kotz, D. M. (2015). The rise and fall of neoliberal capitalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 We are the 99%. (2018, August 29). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/We_are_the_99%

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Occupy Wall Street. (2018, November 07). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occupy_Wall_Street

- ↑ There are two sides to today's global income inequality. (2018, January 23). Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-commentary/the-two-sides-of-todays-global-income-inequality/article37676680/