Science:Science Writing Resources/Grammar and Style

Mechanics and Punctuation

Basic Punctuation

Mechanics are the small parts of your writing that stick everything together to ensure that everything makes sense and that emphasis is placed where you want it to be. Basic punctuation mechanics include commas (,), colons (:) and semicolons (;), apostrophes (‘) and hyphens (-).

When used properly, these mechanics give your sentences the meaning they should have. However, when used incorrectly, they can transform the meaning of the most basic sentence and leave your readers completely baffled as to what you are trying to tell them.

Table 1 contains some basic punctuation mechanics practices that you should consider when writing. This table is not extensive, but provides the most important ‘do’s and don’ts’.

Table 1: Basic punctuation practices

| Punctuation Component | Do | Do Not |

|---|---|---|

| Comma (,) |

|

|

| Colon (:) |

|

|

| Semicolon (;) |

| |

| Apostrophe (‘) |

|

|

| Hyphen (-) |

|

|

Commas

You probably already use commas very frequently, but it can still be hard to always use them appropriately. If you fail to use a comma when there should be a natural pause in a sentence, like here, your readers will be confused. However, if you overuse commas, your readers will be equally baffled as to what you are trying to tell them.

Consider the two versions of a short sentence, below, that is made more confusing by the overuse of commas:

- 1: Thankfully, we, the people of Scarborough, a little seaside town, are deeply, and passionately involved, in nature conservation.

- 2: Thankfully we, the people of Scarborough, a little seaside town, are deeply and passionately involved in nature conservation.

In the first example, the use of commas suggests that the people of Scarborough are deeply in nature conservation and also passionately involved in nature conservation. In the second example, the people of Scarborough are deeply involved and passionately involved in nature conservation.

Consider the two versions of a short sentence, below, that is interpreted completely differently due to the presence of a single (necessary) comma:

- 1: I am very hungry so we should cook Mom.

- 2: I am very hungry so we should cook, Mom.

In the first example, the lack of a comma suggests that Mom should be cooked because I’m hungry. In the second example, the comma suggests that Mom is the person to whom the statement is addressed.

Colons and Semicolons

Colons should be primarily used before you provide lists of items or quote somebody, whereas semicolons are used to link closely related sentences; they can be used when the relationship between these sentences is obvious.

For example, you should use a colon when you list the five basic punctuation mechanics explained here. These are: commas, colons, semicolons, apostrophes, and hyphens. You should also use a colon with a quotation, like this: “The importance of punctuation should never be underestimated,” said Professor in Chemistry, Dr. Reilly.

You should use a semicolon only when the link between to sentences is pretty obvious. For example: Rabbits are always more vigilant when they know predators are watching them; they don’t want to risk being sneaked up on.

Apostrophes

Apostrophes are most often used to signal ownership or to shorten compound words that have been contracted. For example, if the chemistry textbook belonged to Hoshi, you should refer to it as Hoshi’s textbook, and if you are nice to her, perhaps she’ll lend it to you. Contracted compound words like the ‘she’ll’ in that last sentence used to be frowned upon in scholarly writing as people instead preferred writing the two words in full (‘she will’). This way of thinking has generally changed now, so it’s fine to contract words, just as you’d do normally when speaking.

The most common mistake with apostrophes is to use them when you should instead simply pluralize a word. For example, make sure you don’t use an apostrophe when speaking about your recent exams (they were exams, not exam’s).

Hyphens

Learning how to use hyphens correctly in your writing tends to be more difficult than learning how to use the other basic punctuation mechanics outlined here. You most commonly need to use hyphens when you use adjectives to modify the meaning of words that they come immediately before.

For example, the second sentence below contains a modifying adjective:

- 1) The hot Bunsen burner melted a nearby eraser.

- 2) The white hot Bunsen burner melted a nearby eraser.

Without a hyphen (as above), you would think the Bunsen burner was white in colour. The author, however, likely means the Bunsen burner was very, very hot, so you need to use a hyphen to make a compound word, like this:

- 3) The white-hot Bunsen burner melted a nearby eraser.

There are occasions when you need to use more than one hyphen (when you link three or more words, like ‘We dug a seven-foot-deep hole in the garden’). In all cases, when deciding whether you need to use hyphens, assess whether the meaning of your sentences would be the same without your hyphens. If it would, then you don’t need them. This is usually true when you use words ending in y to modify other words. For example, you don’t need a hyphen between ‘happily’ and ‘married’ in the following sentence, because the meaning would be the same:

We are a happily married couple = We are a happily-married couple.

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information on using hyphens appropriately in your science writing, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to hyphenation.

Hyphenation – Quick Quiz

1) Each of the following sentences features the use of none, one, or two hyphens. Which sentences feature the correct grammatical use of hyphens? For the incorrect ones, try to think where the corrections should be made (5 marks).

- a) GEERing Up is a non profit organization that promotes science, engineering and technology to youth in the Greater Vancouver area.

- b) Science-minded students from the University of British Columbia run the program.

- c) Workshops are targeted at students of different ages and it is not uncommon to see six-year-olds enjoying themselves.

- d) The intellectually-stimulating workshops enable students to gain experience in experiments and are designed to increase interest in science, engineering and technology.

- e) The two-hour workshops are designed to give kids a taster, with the more comprehensive week long camps for older students.

2) There should be a total of three hyphens in the following two sentences. Place them where they should go (3 marks).

- Although the workshops only last for two hours at a time, they feature many different fast paced activities to engage students. As well as trying to teach science, engineering and technology, GEERing Up’s mission is also to encourage students to develop social skills and adopt a happy go lucky approach to performing experiments; for this reason, curiosity is encouraged as much as academic success.

3i) Place one hyphen in the sentence below to give it a completely different (but still grammatically correct) meaning (1 mark).

- a) In one of the activities, the volunteer showed students how to use a heavy metal detector to find coins in the soil.

3ii) Why does it matter whether this hyphen is or is not included (1 mark)?

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard at placing hyphens where they need to be, access the answer key here.

Active versus Passive Voice

Active vs. Passive Voice

Many people are confused by whether they are using the active or passive voice when writing, and in which scenario each is preferred. Thankfully, there is a simple way of identifying the two styles; the key to understanding the difference between them is to spot the subject and the object in each sentence, and then selectively order the way you introduce them.

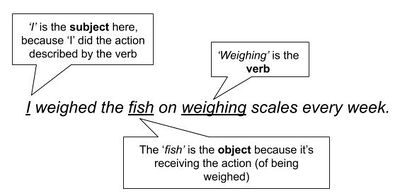

In an active voice sentence, the subject is the element that is doing the action, whereas the object is the element that is receiving the action described by the verb. In contrast, in a passive sentence, the element targeted by the action is promoted to the subject position. This can sound confusing, but a good way to learn this concept is to realize that a passive sentence will result in the subject effectively doing nothing, because whatever is happening is being done to it.

Some examples

Example #1:

1A) Consider the following active voice sentence:

This cannot be a passive sentence because the subject is doing something to the object (weighing it).

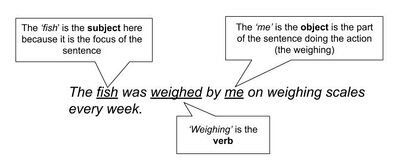

1B) Now consider the passive voice version of the previous sentence:

This cannot be an active voice sentence because the subject is effectively doing nothing.

Example #2:

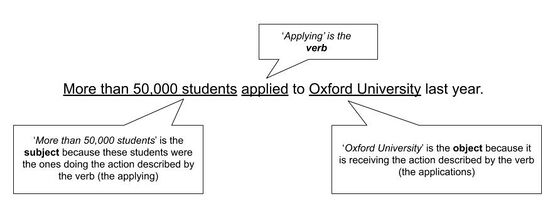

2A) Consider the following active voice sentence:

It cannot be a passive sentence because the subjects are doing something (applying) to the object.

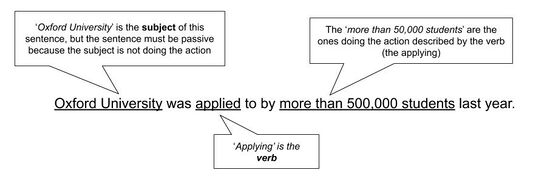

2B) Now, consider the passive voice version of the previous sentence:

You might be developing the impression that using the active voice is always preferable, but this is not the case. Using the active voice is generally preferable because it tends to help you write more concise sentences and makes use of stronger verb forms. However, using the passive voice is acceptable in many situations, and is actually preferable when:

- You want to be purposefully vague. For example: ‘The study was compromised due to a methodological error,’ rather than ‘Mike made an error, which compromised the study.’

- You don’t know the identity of the ‘doer’. For example: ‘The cave paintings were made over 5,000 years ago,’ rather than ‘Someone made the cave paintings over 5,000 years ago.’

- The ‘doer’ is not important. For example: ‘An experimental traffic system will be trialled in British Columbia,’ rather than ‘RoadCorps will trial an experimental traffic system in British Columbia.’

At times, using a mix of active and passive voice may make sense (Anderson 2015).

Why does this matter?

In the examples listed above, the passive voice versions are not especially long-winded, yet if you re-examine them you will notice that they feature more words than their respective active versions. This is of great relevance to you as science writers because it is very important that you always try to communicate things as concisely as possible. When you start to write more complex sentences, the difference in word count can be significant when you compare the active and passive voice versions, and this is important in a setting in which waffly, vague statements are always your enemy.

Along with a lack of conciseness, ambiguity (being vague) is the other unwanted attribute that comes with the use of passive voice sentences (Inzunza, 2021). For example, consider the following active and passive versions of a sentence that might appear in the methods section of your lab report:

3A: Professor Roberts kept the mice in their cages for three weeks. He then released them into the wild and recaptured them three weeks later.

3P: The mice used in this experiment were kept in their cages for three weeks before they were released and then recaptured after they had spent three weeks in the wild.

Note firstly that the active voice version features 24 words in comparison to the 30 in the passive one, yet, importantly, the active version explains exactly what happened and who did what, whereas the passive one leaves these specific details out.

But, sometimes you should use the passive voice…

You might be developing the impression that using the active voice is always preferable, but this is not the case. Using the active voice is generally preferable because it tends to help you write more concise sentences and makes use of stronger verb forms. However, using the passive voice is acceptable in many situations, and is actually preferable when:

1) You want to be purposefully vague.

- For example: ‘The study was compromised due to a methodological error,’ rather than ‘Mike made an error, which compromised the study.’

2) You don’t know the identity of the ‘doer’.

- For example: ‘The cave paintings were made over 5,000 years ago,’ rather than ‘Someone made the cave paintings over 5,000 years ago.’

3) The ‘doer’ is not important.

- For example: ‘An experimental traffic system will be trialled in British Columbia,’ rather than ‘RoadCorps will trial an experimental traffic system in British Columbia.’

4) You are referring to a general truth.

For example: ‘Rules were made to be broken,’ rather than ‘The person who made these rules made them to be broken.’

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information about the active and passive voice, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to effective use of the active and passive voice.

Active and Passive Voice Quick Quiz

1) Are the following versions of the same basic sentence written in the active or passive voice?

- a) Many science students choose to study certain English courses because they want to learn how to communicate science more effectively and gain practice in public speaking.

- b) Certain English courses are chosen by many science students because communicating science more effectively and gaining practice in public speaking are skills that they wish to learn.

- c) Public speaking skills are desired by many students, which is why certain English courses are chosen by such a large number.

2i) Are the following versions of the same basic sentence written in the active or passive voice?

- a) In the end, Dan ran out of time to analyze the data properly, which meant our project was a disappointment.

- b) In the end our project was a disappointment because sufficient time was not left for the data to be analyzed properly.

2ii) Which of the above options is more suitable for the content of the sentence?

2iii) Why?

3) The following sentences are all written in the passive voice. Re-write them in the active voice by rearranging the sentences around the same verb (shown in red for you).

- a) Last week’s chemistry-based lectures were enjoyed by the students.

- b) The topics of beer and liquor production were found to be interesting for them.

- c) Afterwards, that view was heard a number of times by the course instructor.

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard with the active and passive voice, access the answer key here.

Numbers and Units

Numbers and Units

As a science communicator, you will often have to include highly specific information in your written materials. For example, you might be writing a lab report in which you provide numerical details about the method you used in your experiment. Within STEM fields, there are some common practices that will allow you to effectively convey your message, especially when working with numbers.

Some Basic Practices Related to Writing About Numbers

| Practice | Example |

|---|---|

| Spell out small numbers (one to nine). | I performed three experiments yesterday. |

| Use numerals for larger numbers (10 +),except when beginning a sentence. | Mike performed 12 experiments.

Fifteen days later, he collected the data. |

| Use numerals for counts, percentages, decimals, magnifications, and official scales. | We found 8 mice, 12 rats, and 37 rabbits. Mammal populations here have grown by about 30 % in the last five years. |

| Use spaces to make numbers with many digits easier to interpret (do not use commas as they represent the decimal marker in many European and other countries). One space separates three figures, both before and after the decimal, though a four-digit number should not be written with a space. | There are 5194 new species of insect discovered each year. Before rounding, our experimental value was determined to be 98 765.4321 µF. The Boltzmann Constant is defined to be 1.380 649 × 10-23 J/K.

There are approximately 7.5 million insect species on Earth. |

| Avoid having two distinct numbers written next to one another, most simply by rearranging a sentence. | We tested 15 different 19-year-olds not ‘we tested 15 19-year-olds.‘ |

| Spell out names and nouns. | The First Law of Thermodynamics. |

| Use numerals for dates. For short date format, YYYY-MM-DD is advised. | On March 4, we have an exam. Examination date: 2020-03-04. |

| Use numerals for times,

except when writing ‘o’clock’ or ‘hours’ |

The exam begins at 9:30 (09:30),

and finishes at one o’clock (thirteen hours). |

| Use numerals for currency references. | My lunch cost $4.35, but the chips were only 85 cents. |

Always remember to be consistent in your style. If two guidelines clash in one sentence, you will have to favour one over the other. Make sure you continue to favour that one over the other throughout your text.

Some Basic Practices Related to Writing About Units

It is common in STEM fields to abbreviate units of scientific measurement. When writing, it is important to use the correct abbreviations. At best, erroneous abbreviations give the impression that you don’t care about your work, but they also have the potential to confuse your readers.

The table below shows the correct symbols for many commonly used scientific measurements, as well as some of the most important guidelines governing their use in STEM writing.

| Scientific Measurement | Symbol |

|---|---|

| Practices for Appropriate Use | Example |

| Do not pluralize unit abbreviations. | |

| Only use a period after abbreviations if they end a sentence. | |

| Put a space between numerals and unit abbreviations, unless using angular degrees, arcminutes, or arcseconds. The space practice also applies to degrees Celsius and percentages. | |

| Do not capitalize unit symbols unless they are named after people (e.g. kelvin, joule).

Litres have been granted an exception to this practice due to 'l' appearing similar to the number '1' and so can be written as either 'l' or 'L.' Millilitres (and other multiples) should still be written as 'ml.' |

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information about the importance of using numbers and units correctly in your science writing, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to the use of numbers and units in your writing.

Numbers and Units Quick Quiz

1) Read the short paragraph below and spot the errors with the numbers and units, before replacing/rewriting them in the correct format (8 marks):

50 years ago, the Earth’s rainforests were in a much better state; now, due to deforestation, experts predict that up to 50 thousand species go extinct each year, which means that 1 quarter of all species might be gone in another 50 years. As a measure of how rapidly forests can be lost, logging in Amazonian Brazil rose by 70% in just twelve months, between 2017 and 2018. The Amazon is an example of a tropical rainforest, which means monthly temperatures exceed 18 Celsius and there is at least 168 cms of rain each year. Incredibly, in some years, these forests receive more than 1000 centimetre of rain.

2) Read the two sentences below and suggest how these might be confusing (1 mark each), before re-writing them to remove this potential confusion (1 mark each).

- A) Please pass me those 10 10 ml pipettes.

- B) I need to shake the reagents within 10 m after they first mixed.

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard at writing succinctly and dealing with jargon, access the answer key here.

Clarity and Simple Language

Clarity - Using Simple Language

Introduction

Despite needing to communicate at least some technical information to non-specific audiences when writing about science, you should always aim to be as concise and succinct as possible, and limit the use of complex language to ensure that your work is easy to understand.

One golden tip that you should try to put into practice is this: Read your sentences individually and ask yourself whether every single word is necessary. Then ask whether a friend with no science background could read your work without being confused. Often, when thinking like this, you will be able to reduce the length of your sentences and replace certain words to make things flow more smoothly.

When editing your work, you will often find that you can make things more concise by writing in the active voice (rather than the passive). For more information on this, see the Active versus Passive Voice resource on our site.

The Importance of Using Simple Words

One of the greatest misconceptions in writing is the idea that you need to use intellectual-sounding words to give your work a sense of power. Your only goal should be to write something that is easily understood by whoever reads it. The best way of achieving this is to write short sentences containing words used frequently by everybody.

So, instead of ‘elucidating a concept to change the views of your myopic readers’, why not just ‘explain a concept to change the views of you short-sighted readers?’ Similarly, why tell your audience that your invention will have ‘universal applications across the globe’ when they already know that ‘universal’ means that something will apply to every situation? Redundant qualifiers such as this should always be avoided, so, in the previous example, the author should simply have written: ‘universal applications.’

Eliminating Ambiguous Words

It is important to realize that different words can mean different things in certain contexts, and because science is a subject that inherently uses a lot of jargon, this can be a real problem. A word (or phrase) is ‘ambiguous’ if it could potentially mean different things to different people.

For example, the statement that ‘Male salmon grew frighteningly quickly’ could mean they grew much more quickly than expected, or that you were actually scared by their speed of growth. Similarly, the statement that ‘these males grew significantly faster than females’ is also potentially problematic because ‘significance’ means something different when it refers to a statistical comparison than when it is used to convey something noticeable; so, a scientific audience and a non-scientific audience might interpret the meaning very differently.

Some Examples

These examples are designed to highlight the importance of writing with clarity by contrasting short, simple, succinct sentences with long-winded, wordy, potentially ambiguous versions:

1A) Scientists recently used computer programs to show how some plant species become common when rabbits and deer are prevented from accessing forests.

1B) Scientists recently utilized computer models to highlight how certain angiosperms become dominant in frequency when mammalian herbivores are preferentially excluded from gaining access to forest habitats.

2A) The new electricity system will surprise its developers later this year when it is installed in many homes by increasing the inefficiency problem they designed it to solve.

2B) The novel electricity system will shock its proponents later this year when it is wheeled out to many residences, by exacerbating the inefficiency problem it was designed to dissolve.

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information about the importance of clarity (and using simple language) in your science writing, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to clarity in writing.

Clarity – Using Simple Language Quick Quiz

1) With clarity in mind, choose the best option from the following versions of each sentence (2 marks):

- A(i): I am finding it difficult to work with my new electronics lab partner. We often get our wires crossed.

- A(ii): I am finding it difficult to work with my new electronics lab partner. We often misunderstand one another.

- B(i): Things are progressing better with my genetics partner though.

- B(ii): Things are evolving better with my genetics partner though.

2) Briefly explain which potential problem each of the sentences has in common below (1 mark), before re-writing each sentence to remove the problem (3 marks):

- A) This new ice-based weapon is really chilling.

- B) But it isn’t as ground-breaking as the device that measures earthquakes more accurately than ever before.

- C) However, both of these products were announced by a PR company with a history of making relatively ineffective space travel inventions seem astronomically important.

3) Choose the most suitable option for each ‘underlined section’ in the passage below (4 marks):

- New research has shown that within a given group/population of birds, mammals, or fish, individuals/conspecifics/singletons conform to one of two foraging strategies; they are either adventurous consumers (AC), or dietary conservatives (DC). ACs quickly try new foods before deciding whether or not to include them in their diet, whereas DCs are disinclined/reluctant/reticent/loath to try new foods. Interestingly, however, if they see competitors eat the new food and enjoy it, they will quickly incorporate it onto their own personal menu. Therefore, particularly when food is scarce, competitors actually help DCs gain nutrition from their environment in a/an secondary/indirect/ancillary/serendipitous/oblique way.

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard with clarity (and using simple language), access the answer key here.

Grammar

Grammar can be loosely described as the set of structural patterns that govern the composition of writing within a specific cultural or social context, including those of specific academic disciplines. This page focuses on some of the grammatical structures that are particularly important for those writing in STEM fields. Each grammatical structure allows writers to communicate clearly and purposefully to their audience.

Articles: Using the definite article – ‘The’

In STEM fields, writers use the definite article ‘the’ to refer to something specific (or ‘definite’).

The important thing to bear in mind is that a word on its own cannot necessarily be categorized as requiring the definite or indefinite article; instead, it is the way that you refer to that word that determines which article you should use.

For example, you can write: “I saw the anteater at the zoo,” if you are referring to a specific anteater (perhaps there is only one, or this anteater has been in the news lately and people can be expected to know the specific anteater you are referring to). However, if you saw one anteater of five or six that were in the zoo, you should write: “I saw an anteater at the zoo.”

One quick tip to see whether you require an article in your writing is to read the sentence without it and see if it means the same thing; if it does, then you can safely remove the article.

For example: “Anteaters like the sunshine,” means the same thing when written as: “Anteaters like sunshine,” so you need not use the definite article in this case.

Articles: Using the indefinite articles - ‘A’ and ‘An’

Writers in STEM fields use the indefinite articles, ‘a’ or ‘an’, to refer to something non-specific (or ‘indefinite’) in their writing.

You should speak a word rather than read it to help you decide whether to use the indefinite article ‘a’ or ‘an’; although there are some exceptions, you should generally use ‘a’ when referring to a word that makes a consonant sound, and use ‘an’ when referring to a word that makes a vowel sound.

For example, you should write: “A rabbit…” or: “A giraffe…” because these words begin with consonants (and make consonant sounds when spoken). However, you should write: “An elephant…” or: “An anteater…” because these words begin with vowels and make vowel sounds when spoken).

The reason that it is helpful to speak words aloud when deciding whether to use ‘a’ or ‘an’ is because ‘silent letters’ could otherwise confuse you when simply seeing them written.

For example, you should write that: “Professor Reilly scored a hat-trick,” (because the ‘h’ in this word makes a consonant sound), but you should write: “The same player acted in an honourable way when passing up another goal due to an opposition player being injured,” (because the ‘h’ in this word is silent, which means the ‘o’ is the first letter you hear, and this ‘o’ makes a vowel sound).

This same general rule applies when using acronyms in your writing, which is why you should write: “A NASA spacecraft is currently taking pictures of Mars,” but: “An EPA directive ensures that businesses attempt to reduce their carbon emissions.”

Tenses

Tenses help writers communicate when something happened (or will happen). For example: “I study biology,” refers to the present (I am currently studying biology), whereas: “I studied biology,” refers to the past (as it implies that I no longer study biology).

There are six basic tenses that we use on a frequent basis, and these are highlighted below, with examples. Note: Consider how the implication of the sentences written for the Present Perfect and Simple Past differ based on the addition of one word (have). Although it might be useful to know the differences between these six basic tenses, and to be able to write simple sentences in each one, the most important thing is to be able to recognize when the tense shifts in your writing. Tense-shifting can lead to confusion for your reader. For that reason, you are advised to use the same tense within each sentence (and often within a complete paragraph).

- Simple Present: I study biology

- Present Perfect: I have studied biology for 12 years

- Simple Past: I studied biology for 12 years

- Past Perfect: I had studied biology

- Simple Future: I will study biology

- Future Perfect: I will have studied biology

How might your audience interpret each statement?

For example, writing: “I have studied biology for 12 years, and I also study chemistry,” might be confusing because it’s not clear from this sentence how long you have studied chemistry for. Had you written everything in the present perfect tense (I have studied biology for 12 years, and I have also studied chemistry for seven) this potential confusion disappears.

Subject/Verb Agreement

In scholarly writing within STEM fields, it is important to ensure that the verb in each sentence matches or “agrees with” the subject of the sentence. The three examples below outline some particularly tricky sentence structures.

Tip: Remember throughout that the subject comes at the start of a sentence, and it is this – and its relationship with the main verb - that is important.

1. Do not be distracted by anything that comes in between the subject and the main verb, as in:

- “ Our friend Suzy, along with her fellow physics club members, is [NOT ‘are’] anxious about tomorrow’s test.”

- “ My classmate, with all his textbooks, takes up [NOT ‘take up’] a whole library desk.”

2. Collective nouns that imply more than one person/thing are involved are still treated as singular subjects, as in:

- “ The team runs [NOT ‘run’] during training.”

- “ The Physics Club watches [NOT ‘watch’] videos at their meetings.”

3. When your writing includes a compound subject that is joined by ‘or’ or ‘nor’, the verb should agree with the part of that subject that is closest to the verb, as in:

- “ Neither Suzy nor her friends, Claire and Ash, want [NOT ‘wants’] to take the new class.”

- “ Alana or Jonny is [NOT ‘are’] is going to write up the lab report.”

Parallel Structure

Much like consistency in verb tense, consistency in the form of linked parts in a piece of writing is important for readability. By this, we mean that the verb endings and related phrases and clauses within a sentence should all follow the same pattern.

For example: “Scientific understanding is improved by researchers exploring new possibilities and communicating their findings,” is written in parallel form and sounds smooth when you hear it.

On the other hand: “Scientific understanding is improved by researchers exploring new possibilities and when their findings are communicated,” is not written in parallel form, and is consequently harder to interpret. This should be corrected by changing the red portion to “…communicating their findings.”

Parallel structure in your writing is useful whether you are writing complete sentences or listing things.

For example, in this resource we are hoping to help you: use the definite and indefinite articles appropriately, write your tenses consistently, check that your subjects and verbs align correctly, and ensure that the parallel structure of your writing reads smoothly.

Quick Quiz

Grammar – Quick Quiz

Do the following sentences show the correct use of the indefinite and definite articles? Note: If incorrect, think about how you would re-write them correctly.

Q1: The only US-produced single I bought last summer went on to be a one-hit wonder. Q2: A holistic approach to medicine involves treatment of a patient as well as the ailment. Q3: A uncontrolled research study can never provide useful results. Q4: The black grouse is an honest bird; males make themselves available to females for mating and line up in order of their sex appeal.

Do the following sentences mix tenses? Note: If they do, think about how you could re-write them to make sure they were in the same tense.

Q5: I will probably have graduated by the time I will know what sort of career I want. Q6: I wanted to travel through South America ever since the itchy-feet bug bit me.

Which form of the verbs should be used to fill in the gaps in the following sentences?

Q7: NASA’s astronauts, like Mike, the bomb disposal specialist I know, ARE/IS trained under simulated conditions before being asked to work in real-life situations. Q8: Neither I, nor my colleagues, FEEL/FEELS that science funding bodies should favour applied research proposals over basic research proposals.

Q9: Which of the sentences in the paragraph below is NOT written in parallel form? Note: Think about how you could re-write it to make sure it is.

Sentence 1: When lecturing, my professor mimics a TV reporter by presenting information in a newsworthy way, removing any boring parts, and never forgets to explain important jargon. Sentence 2: At the end of her most recent class, we closed our books, were turning off our computers, and pushed our chairs under the desks when the next class barged in.

Q10: Which of the sentences in the paragraph below is NOT written in parallel form? Note: Think about how you could re-write it to make sure it is.

Sentence 3: The first student to enter was listening to his iPod, the second was chatting, and the third shouted a coffee order to his friend. Sentence 4: He soon realized everyone had heard him, so I bet he wished he could have turned back time, switched off his iPod, and walked into the classroom as normal.

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard with grammar, access the answer key here.