Gerrymandering

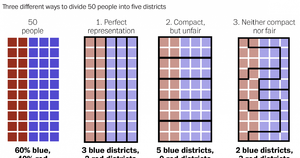

Gerrymandering is the process of manipulating district boundaries with the intent of giving an unfair advantage to the political party. This is accomplished by the careful division of demographics within different districts. It has been argued that the process of gerrymandering undermines the ‘one person, one vote’ mentality that is meant to be the driving force behind Western democracy, and that it disproportionately affects groups of racial minorities.

Process

Gerrymandering usually takes place at the beginning of the decade, when districts are redrawn based on census information to account for population movement.[1] The political party in charge of the process may use demographic information provided by the census to create a favourable distribution of different ethnic or sociopolitical groups.

The two main ways in which a gerrymander can redistribute the population are known as packing and cracking. Packing involves condensing people who are likely to support the opposing party into one group, so that the other party is able to have representatives elected in all the groups around it. Cracking involves breaking up these groups, redistributing them so that they are minorities in the new districts.[2]

History

Gerrymandering has a long history in United States and global politics. Here are some examples that help to define how it can be used.

Governor Elbridge Gerry

The term ‘gerrymander’ originates from Elbridge Gerry, a former Governor of Indiana who manipulated district boundaries to secure seats for the Democratic-Republican Party in 1812.[3] Gov. Gerry’s critics commented that one of his redesigned districts resembled a salamander, and created the term ‘gerrymander’ as a portmanteau of the animal and his name.[4]

1981-82 Supreme Court Case

The practice of gerrymandering was taken to the Supreme Court in 1981, on the grounds that the redrawing of Indiana district boundaries created an unfair advantage for the Republican party, and that the action constituted discriminatory intent. While the Supreme Court ruled there was discriminatory intent behind the process, they could not find evidence to conclude that it led to the violation of equal protection, and did not constitute criminal activity.[5]

Researchers at Ball State University conducted an independent study following the ruling to show the effect that gerrymandering had in the election. Their study concluded that for the most part, the incumbent party was re-elected to gerrymandered districts. Out of the twenty-six gerrymandered districts in which control did shift, it was in favour of the Republican party. The study concluded that gerrymandering was done with the intention of securing power in ridings, as well as shifting votes in 50-50 districts in order to make them into safe wins.[6]

2012 Election

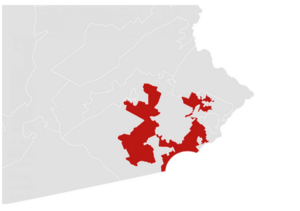

Political scientists estimate that gerrymandering caused the Democratic party to lose between five to fifteen seats in the 2012 election.[7] The most extreme example of gerrymandering’s effect on the outcome occurred in Pennsylvania, in which Democrats received 51% of the vote, but only five out of eighteen seats.[8] Pictured is an example of a gerrymandered district in Pennsylvania.

Canada: 2015 Election

Leading up to the Canadian federal election in 2015, several ridings were redrawn in a manner which could prove advantageous to the incumbent Conservative party. For example, poll data from the 2011 election suggested that the Conservatives would win the new Vancouver-Granville riding with only 35% of the vote. Activist group LeadNow launched their ‘Vote Together’ campaign with the goal of creating a strategic voting bloc in ridings like this in order to keep Conservative MPs from being elected.[9]

Implications

Critics argue that the process of gerrymandering hurts the ‘one-person, one-vote’ nature of Western democracy by manufacturing situations in which one party has an overwhelming advantage. openDemocracy’s Stein Ringen describes the process as reducing the election in a gerrymandered district “to a mere ritual to verify the pre-determined result.”[10] The effect of this is magnified on racial minorities, who often find their communities either packed or cracked in order to silence their already under-heard voices.[11]

A side-effect of gerrymandering that can be overlooked is its tendency to create polarized and partisan candidates. For example, if a district contains 85% Democratic voters due to gerrymandering, the representative is heavily incentivized to cater to that group. However, if the district was split 50/50 in representation, the representative would be forced to consider both sides.[12] As Cranor et. al concluded that one of the goals of gerrymandering is to create fewer 50-50 districts,[13] it follows that the process of gerrymandering creates more polarized candidates.

References

- ↑ OpenDemocracy, "Democracy in America, part 1: What's wrong with gerrymandering?", https://www.opendemocracy.net/stein-ringen/democracy-in-america-part-1-what's-wrong-with-gerrymandering

- ↑ NoLabels, "Just the Facts: Gerrymandering", https://www.nolabels.org/blog/just-facts-gerrymandering/

- ↑ OpenDemocracy, "Democracy in America, part 1: What's wrong with gerrymandering?", https://www.opendemocracy.net/stein-ringen/democracy-in-america-part-1-what's-wrong-with-gerrymandering

- ↑ NoLabels, "Just the Facts: Gerrymandering", https://www.nolabels.org/blog/just-facts-gerrymandering/

- ↑ American Journal of Political Science, "Anatomy of a Gerrymander," p222, http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/2111260

- ↑ American Journal of Political Science, "Anatomy of a Gerrymander," pp236-237, http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/2111260

- ↑ OpenDemocracy, "Democracy in America, part 1: What's wrong with gerrymandering?", https://www.opendemocracy.net/stein-ringen/democracy-in-america-part-1-what's-wrong-with-gerrymandering

- ↑ NoLabels, "Just the Facts: Gerrymandering", https://www.nolabels.org/blog/just-facts-gerrymandering/

- ↑ LeadNow, "VoteTogether: Vancouver Granville", https://www.votetogether.ca/riding/59036/vancouver-granville/

- ↑ OpenDemocracy, "Democracy in America, part 1: What's wrong with gerrymandering?", https://www.opendemocracy.net/stein-ringen/democracy-in-america-part-1-what's-wrong-with-gerrymandering

- ↑ OpenDemocracy, "Democracy in America, part 1: What's wrong with gerrymandering?", https://www.opendemocracy.net/stein-ringen/democracy-in-america-part-1-what's-wrong-with-gerrymandering

- ↑ NoLabels, "Just the Facts: Gerrymandering", https://www.nolabels.org/blog/just-facts-gerrymandering/

- ↑ American Journal of Political Science, "Anatomy of a Gerrymander," p236-237, http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/2111260