Gender Discrimination in China

Overview

Gender discrimination in China has its very own cultural and economic roots deep in the history. It did not begin with just the One Child Policy, but the male lineage family structure from ancient period. The preference of baby boys had been enhanced since Deng Xiaoping introduced the One Child Policy. In recent years Chinese society begins to see the challenge and danger brought by those practises.

Gender discrimination is evidenced through out Chinese history. One of the famous examples is Foot Binding. This extreme torture of women body reflects how females were positioned for a very long time. On the other hand, it is true that China has grown to a really big developing nation and one can even say developed in many of her cities. Just like many other Asian countries, western values and doctrines are influencing China. As China's economic and social status are making progression, one may no longer see foot binding or the traditional male lineage family nowadays, but surely there are still many old or new issues related to China's own cultural and social references from the past.

Although Feminism in China did not come to stage officially until the late 20th century. There are many studies and reports regarding this issue in today's People's Republic of China. Chinese society is becoming more aware about gender discrimination.

One Child Policy

The family planning policy, known as One Child Policy was introduced in 1978. It was enacted in 1980 to force families in China to have only one child, penalties are usually fines that go from 3 to 6 annual family incomes depend on provinces and regions. There was an example where a couple in Guangzhou (3rd largest city in mainland China) were asked to pay the fee. "This is what happened recently in Guangzhou: a pregnant woman accompanied by her husband strutted in to visit their local birth control office. They took out a red bankbook, flung it on the desk and said, "Here is 200,000 yuan (US$26,570), impose as much of a fine as you want. We need to take care of our future baby. Please do not come to disturb us.” [1]

Since China still use the Hukou System, which registers every citizen in their respective town/city. Illegal babies are not allowed to register in the system therefore they can't go into the tax system and can't apply for any public school and health care. [2] Some researches show that the policy successfully averted at least 200 million births between 1979 and 2009.[3]

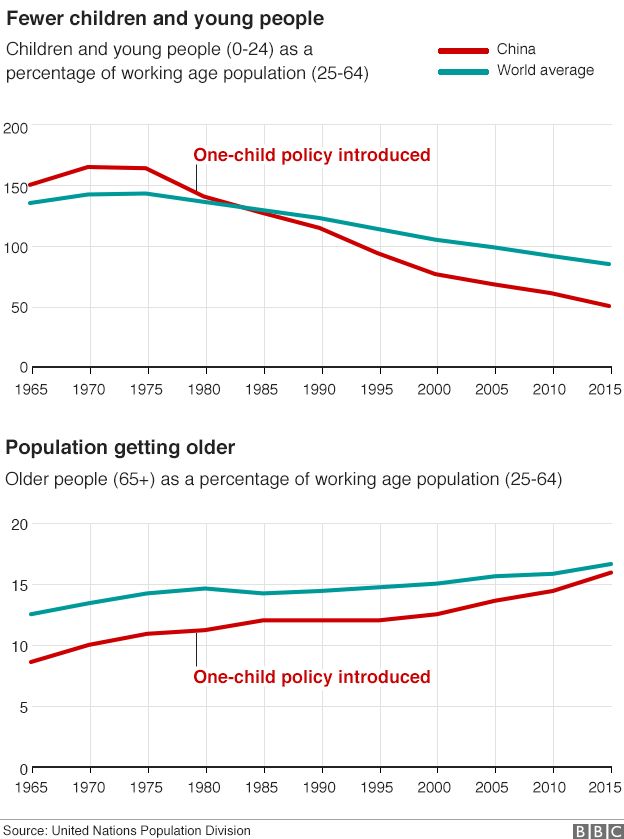

The following image shows the demographics of China in comparison to the World average, highlighting the effects on the world population when the One-child policy was introduced.

< >

>

Gender Discrimination in Family & Reproduction

The strict patrilineal family system bestows on male descendants economic, sociocultural, and religious benefits and obligations which create preference for sons. State policies also affect gender equity (Murphy 2003). Thus son preference and discrimination against girls are affected by institutions, culture, economy, and public policies (World Bank 2002, p. 40).[4] In the countryside today, the family is still the dominant provider of old-age support. The traditional gender division makes women economically dependent on men (Chow and Berheide 2004, p. 142–143). Partly due to this economic dependence, married-out daughters provide mainly auxiliary help such as emotional support and help with daily activities for their parents, while sons provide the basic economic support (Sun 2002). The dire need for economic support in old age makes rural people favor sons. [5]

Gender discrimination leads directly to missing females and the unbalanced sex structure of China’s population, which affects important features of the country’s demography, such as population size, rate of increase of the elderly, insufficient people of working age, declining number of births, and problems with the marriage market. ‘‘Missing females’’ decreases the current population size, and although this effect may currently be small, the effect of these missing girls and their female offspring on future population growth is important. The cumulative effect on population growth should not be underestimated (Cai and Lavely 2003; Attane, 2006). Missing girls decreases the number of births, and this will certainly affect the aging of China’s population. The total number of working-age people will also be affected by a decrease in the population. The shortage of marriageable females has caused a squeeze on males in the marriage market (Tuljapurkar et al. 1995; Das Gupta and Li 1999). [6]

Pre-natal sex determination and sex-selective abortions for non-medical reasons are illegal in China. However From the data alone, many researchers believe selective sex abortion is still an existing issue regardless of the law stating it is illegal. Sex ratio data records from 1960 where the ratio was about an even number, and by 1990 it grew to 111.9 birth of boys of every 100 girls. In 2010 the number grew all the way to 118, which seems unlikely just by the fact of family’s preference to have sons. While the government has taken measures to regulate the unbalanced sex ratio, it appears the social value preferring sons over girls cannot be so simply regulated.

Consequence

1. Sex Ratios at Birth (SRB)

"With the stringent implementation of the one-child policy, China’s sex ratio at birth (SRB) has risen continuously. In 2000, the SRB in those 1.5 children policy areas (namely, those areas where a second child was permitted if the first was a girl) was 124.7, which is 15.7% points higher than the ratio 109.0 in two-children areas, indicating clearly the impact of sex-selective abortions (Gu et al. 2007)" [7]

2. Excess Female Child Mortality (EFCM)

There is no agreement on any data bases of this statistic, however, according to Wang's study, it is believed that there is approximately 10% difference in male and female infant mortality rates since 2000, where female babies are more likely to be abandoned. [8]

3. Shortage of Marriageable Females

Along with the rise SRB, China is suffering from the shortage of marriageable females. Although no reliable data is found on this course, some Chinese news website suggest that about 37 million men would not be able to find their female partners.[9]

Gender Discrimination at Work

Impacts of Capitalism

China experienced enormous economic reformation in the past 30 years. Capitalism and market economy had brought this country prosperity and industrial growth, however, some observe that these changes also bring gender discrimination. According to Liu, Meng and Zhang, "The increase in gender wage differential due to marketization is much larger than any increase in differential that may arise from more gender discrimination" (Liu, 2000) [10] A market-oriented wage determination system has created a market where wage and gender preference are now decided by employers merely just like any other economies, thus gender discrimination became more obvious and clear in today's China. Traditional ideologies plus the new market together form new waves of gender discrimination against women in China. Employers tend to view women as weak and vulnerable not only from office but also from what they have learned from family practises, such as abandoning female infants, despising female siblings. Chinese women are definitely facing a more challenging gender discrimination in the labour market.

Although according to article 13 of the Labor Law of the People's Republic of China, "Women shall enjoy equal rights as men in employment. Sex shall not be used as a pretext for excluding women from employment during recruitment of workers unless the types of work or posts for which workers are being recruited are not suitable for women according to State regulations. Nor shall the standards of recruitment be raised when it comes to women," [11] it is really hard to enforce the regulation in practice. Just like other countries, discrimination of race, age or gender are implicitly expressed in the labour market of China.[12] Kuhn and Shen's research shows that the situation in China is rather grim as they show that " during our 20-week sample period, over one third of the firms that advertised on the job board which caters to highly educated urban workers seeking private sector jobs—placed at least one ad stipulating a preferred gender. We also find, perhaps surprisingly, that the share of ads favoring men versus women is roughly equal. Put another way, when it is legal to express gender preferences in job ads, a significant share of employers chooses to do so and uses gendered ads to solicit women as often as men.[13]

Gender Discrimination in Work Ad

The table below is a research done by Kuhn and Shen, which was based on online job advertisements. It is shocking to see even within certain gender preference there are also some discriminations against height,age, and subjective beauty.

SHARE OF JOB ADS EXPRESSING A GENDER PREFERENCE, FOR SELECTED SUBSAMPLES OF ADS[14]

| Ad characteristic | Requesting women | With no gender preference | Requesting men |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad requests beauty | .239 | .723 | .038 |

| Ad requests both beauty and height | .559 | .383 | .059 |

| Ad requests beauty, height, and maximum age under 25 | .871 | .103 | .026 |

Feminism in China

The People's Republic of China(PRC) established the All-China's Women Federation in 1949 to protect women's rights and promote equality between men and women.[15] Many famous Chinese feminists appeared throughout the 20th century:

He Zhen

He's essay on "On The Question Of Women's Liberation," opens with "for thousands of years, the world has been dominated by the rule of man. This rule is marked by class distinctions over which men -- and men only -- exert proprietary rights. To rectify the wrongs, we must first abolish the rule of men and introduce equality among human beings, which means that the world must belong equally to men and women. The goal of equality cannot be achieved except through women's liberation."(Liu, 2003)[16] She was also famous for the essay "What Women Should Know About Communism" [17]

Li Xiaojiang

In a essay by Lingzhen Wang, Li Xiaojiang, a modern Chinese feminist is well introduced, "Li Xiaojiang, the featured author in this special issue, is the most representative figure of the 1980s women’s studies movement. She was the first person in the history of socialist China (from 1949 on) to publish a feminist theoretical article revising Marxist views on women’s liberation (1983), to organize a women’s studies association independent of the state (1985), to advocate a theoretical framework for developing women’s studies as an academic discipline (1986), to establish a center for women’s studies (1987), and to edit and publish a series of women’s stud- ies books (1988).[18]

Conclusions

Kuhn and Shen suggest that "Policies at various administrative levels should play the dominant role in eliminating son preference and gender discrimination. In order for this to happen, issues concerning gender must be integrated into public policies and their implementation. The goal must be to change the traditional ideology, to enhance female social status, to achieve equality for males and females in social life, to optimize population size, structure, and distribution, all of which can help promote China’s socially sustainable development" [19]. It is true that gender discrimination in China is often deteriorated by traditional ideologies. Education should be another focus pertaining to this issue especially in rural regions. The ministry of publicity can also devote more into the campaign of promoting gender equality. State should be giving more legal support in both protecting female infants and the labour market. As of this point, China still has a long way to go.

References

- ↑ "Heavy Fine for Violators of One-Child Policy -- China.org.cn." Heavy Fine for Violators of One-Child Policy -- China.org.cn. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ "Hukou System." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Olesen, Alexa. "Experts Challenge China's 1-child Population Claim." Boston.com. The New York Times, 27 Oct. 2011. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). The summeray of gender discrimination of china (Order No. H356300). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026781799). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1026781799?accountid=14656, 620

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). The summeray of gender discrimination of china (Order No. H356300). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026781799). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1026781799?accountid=14656, 621

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). The summeray of gender discrimination of china (Order No. H356300). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026781799). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1026781799?accountid=14656, 622

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). The summeray of gender discrimination of china (Order No. H356300). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026781799). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1026781799?accountid=14656, 622

- ↑ Wang, J. (2008). The summeray of gender discrimination of china (Order No. H356300). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026781799). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1026781799?accountid=14656, 627

- ↑ http://scitech.people.com.cn/GB/5956149.html

- ↑ Liu, Pak-Wai, Xin Meng, and Junsen Zhang. "Sectoral Gender Wage Di¨erentials and Discrimination in the Transitional Chinese Economy." Journal of Population Economics 13.2 (2000): 331-52. SpringerLink. Springer-Verlag. Web. 7 Apr. 2015. <http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s001480050141>.

- ↑ http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=705&CGid=

- ↑ Kuhn, Peter, and Kailing Shen. 2013. "Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China*." Quarterly Journal Of Economics 128, no. 1: 287-336. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 14, 2015).

- ↑ Kuhn, Peter, and Kailing Shen. 2013. "Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China*." Quarterly Journal Of Economics 128, no. 1: 287-336. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 14, 2015).

- ↑ Kuhn, Peter, and Kailing Shen. 2013. "Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China*." Quarterly Journal Of Economics 128, no. 1: 287-336. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 14, 2015).

- ↑ http://www.women.org.cn/zjfl/fljj/456888.shtml

- ↑ Liu, Huiying (2003). "Feminism: An Organic or an Extremist Position? On Tien Yee as Represented by He Zhen". positions: east asia cultures critique 11 (3): 779–800.

- ↑ http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/hezhen_women_communism.pdf

- ↑ Wang, L. "Gender and Sexual Differences in 1980s China: Introducing Li Xiaojiang." Differences 24.2 (2013): 8-21. Brown University and Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. Web. 7 Apr. 2015.<http://differences.dukejournals.org/content/24/2/8.refs?related-urls=yes&legid=dddif;24/2/8>.

- ↑ Kuhn, Peter, and Kailing Shen. 2013. "Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China*." Quarterly Journal Of Economics 128, no. 1: 287-336. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed February 14, 2015).

20. Junhong, Chu, June 2001, “Prenatal Sex Determination and Sex-Selective Abortion in Rural Central China,” Population and Development Review, Vol. 27, Iss. 2, p. 264. Retrieved 3 Sept 2010.