GRSJ224/withinthelaw

While the justice system is expected to be a strong example of unbiased opinions searching for truth, this is hardly the case. We constantly see many examples of the justice system showing discrimination towards various minority groups based on race, skin colour, gender, or sexuality. This article focuses on this type of systemic discrimination within the Canadian context.

History

Tracing back decades shows that as long as humans have been ruled by law, there has been bias towards those who are perceived to be superior. We can find an early example of this in Orestia by Aeschylus. The trilogy showcases a justice system, where the courts ruled in favour of a man who committed the same crime as a woman, letting him go free, while she was killed for her crimes. This is only one example of many in history where we see the legal system displaying preference towards a party based on their gender (and etc.).

Segregation

The case of Viola Desmond (1946) is an example of segregation in Canadian history. It also gives us a glimpse of systemic discrimination within the legal system.[1] When Desmond was forced to leave a movie theatre after attempting to sit in a "whites only" section, leaving her with physical injuries, she decided to take legal action against the theatre. Unlike most other female visible minorities, Desmond went through the trouble of hiring a well-respected lawyer. However, through the process of the trial,her claims were shut down and her lawyer decided to not confront the issue of segregation, and instead focus on the physical assault she faced. The lawsuit failed at attacking the issues of racism enshrouded in law, essentially supporting racial segregation in Canada.

Not only was racial segregation allowed in privately owned spaces, but it also occurred within public spaces, such as schools.[2] While schools now are considered to be a safe space, dedicated to learning, sharing ideas, and develop children into adults, they have not always been a secure environment to do so in. Many schools refused to accommodate Black children who tried to attend white-only schools, thus forcing them to follow the segregated philosophy throughout the 20th century. This practiced continued until 1983, when the last segregated school in Canada was closed in Nova Scotia.

Discriminatory Laws

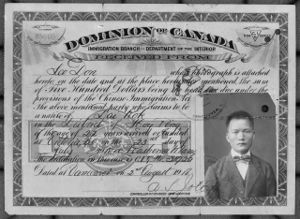

Throughout history, there have been many examples of the Canadian government exercising its legal power to discriminate against visible minorities. One such example of this is how the Canadian government dealt with Chinese immigration between the 19th and 20th centuries. Under the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, Canadian parliament placed a head tax on new Chinese immigrants.[3] The initial cost of coming to Canada was $50, later raised to $100, then $500, before this document was abolished in 1923. Following the termination of the Act, a new law replaced it. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (more commonly known today as the Chinese Exclusion Act) was created with the purpose of restricting Chinese immigration into Canada. This Act applied not only to those coming from China, but any of those of Chinese decent (with the exception of having merely Chinese ancestry on the female side of the family). This Act remained effective until it was deemed to not comply with the UN charter, thus it was repealed in 1947. Independent Chinese immigration did not occur until after Canadian Immigration policy adopted the points system in 1967.

Present System of Justice

Racial Profiling

Racial profiling occurs when law enforcement officials judge a person based on their looks, and relate that to their likelihood to commit a crime. This could include when a security guard follows a man around the store because he is wearing a hoodie and "looks suspicious". Other times, these situations can also escalate to incidents such as the Trayvon Martin case, where a community watch volunteer shot and killed a young man due to the colour of his skin, which he had presumed to not belong in the neighbourhood (the case decision may be read here).

A study from Kingston, Ontario showed that police are nearly 4 times more likely to stop a black person than a white person, and ~1.5 times more likely to stop an Aboriginal person than a white person.[4] In a mostly white city, these statistics are hugely disproportionate. This is a prime example of people being targeted based purely on their ethnic background, and shows how racial profiling negatively affects members of visible minority groups.

Incarcerated Persons

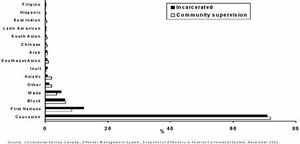

The trend we've seen so far in relation to how the law treats visible minorities and caucasian persons follows through to convicted offenders. Research has shown that the population within federal prison institutions is made up of 12% First Nations, 6% African Canadian, and 11% of various other racial minorities.[5]While that doesn't necessarily seem like a lot, it is when you begin to consider the Canadian population as a whole. According to a 2001 survey, only 13% of the population was considered to be a member of a visible minority group. This means that the prisons show a disproportionately large amount of minority offenders, which is an unlikely phenomenon to be true and is more likely a representation of racially biased views within the justice system. These statistics have shown to be on an upward trend. The reported 11% visible minorities occupying federal prisons at the time of the report is an increase from 9% ten years prior.

A report issued in 2016 states that overall adult incarceration rates are declining, however Aboriginal individuals accounted for one in every four adults being admitted to the correctional system, while only representing ~3% of the Canadian population.[6] This overrepresentation is more prominent for females, as well. The study shows that Aboriginal females represented 31% of female offenders in federal custody, and Aboriginal males represented 22% of males. This trend can be found with other minority groups, to a lesser degree.This includes African Canadian individuals, who account for 6% of offenders in federal correctional facilities, yet only 2% of the Canadian population.

References

- ↑ Backhouse, Constance. ""Bitterly Disappointed" at the Spread of "Colour-Bar Tactics": Viola Desmond's Challenge to Racial Segregation, Nova Scotia, 1946." Law in Society: Canadian Readings, edited by Nick Larsen and Brian Burtch, Nelson, 2010, pp. 108-147

- ↑ "End of Segregation in Canada." Historica Canada. Web. 06 April 2017.

- ↑ Chan, Arlene. "Chinese Head Tax in Canada." Historica Canada 06 Sep 2016. Web. 06 April 2017.

- ↑ CBC News. "Police stop more blacks, Ont. study finds." CBC News. 26 May 2005. Web. 06 April 2017.

- ↑ Trevethan, Shelley and Christopher J. Rastin. A Profile of Visible Minority Offenders in the Federal Canadian Correctional System. Correctional Service Canada, June 2004. R-144.

- ↑ Reitano, Julie. "Adult correction statistics in Canada, 2014-15." Statistics Canada, March 2016.