GRSJ224/Women in Slasher Films

Horror Films

The classic horror film depicts sexual desires that are channeled into normative heterosexuality, which configures into the hero of the narrative, who takes his place within the order of the patriarchal society. [1] The sexual desires, or pleasures, are associated with the “specious good - bourgeois habits, manners, and morals,” [2] which also classify the society in horror films. As a result, the horror of the film is almost always depicted through the human body, which is the visible sign of sexual and gendered identity. [3] Horror films display an underlying fetishizing of the visual appearance of female characters, [4] putting an emphasis onto the focus of the gaze that invites and reinforces “the active male viewer and the passive female object.” [5] This particular focus on the female as object “flirts directly with the threat of castration” [6] and emphasizes the benefits of identifying as male or masculine. This idea of “castration” is obviously supported by the excessive violence within the genre and also depicts a “displacement of sex onto violence.” [7]

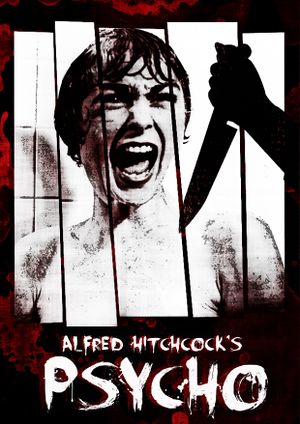

Hitchcock's Psycho: Kickstarting the Subgenre

Director Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho is often credited with introducing new tropes within the horror genre that inspired the slasher subgenre. The film presents “a vague psychoanalytic explanation locating the cause of madness in a traumatic event in the past involving the character’s developing sexual identity” [8] and clearly utilizes some tropes of the horror genre. A narrative technique that Alfred Hitchcock used often in his films was, “express the dread of female sexual difference” [9] and this is apparent in Psycho with the character Marion Crane, who is brutally murdered in the iconic shower scene. This act of sexualized violence is what influences the styles of later horror films. [10] Even though Psycho did push boundaries for filmmaking in Hollywood at the time, we never see the knife actually go through Marion, but as the genre progresses the boundaries get pushed further and the killings become more explicit and gruesome (Grant 8). Horror films since the release of Psycho have a “reliance on explicit bodily violation,” [11] which has become even more prevalent in recent years because of improved digital and prosthetic special effects. Bodily excess through violence, ecstasy shown by ecstatic violence, sadomasochistic perversion, and excessive blood are all slasher film conventions, as well as conventions that happened more frequently post Psycho. [12]

Slasher Films

Genre Conventions

The roles of the female characters in slasher films are depicted as either, “tomboys or teenaged sex fiends who somehow deserve their dismemberment at the hands of a Jason or Michael Meyers.” [13] As a result the female body is victimized because it is either not sexualized enough, “tomboy-ish,” or overtly sexualized to the point that it’s degenerate. The female role has been reduced to a physical body, which depicts stereotypes that function to serve the narrative. The violence that acts out this misogyny demonstrates that the woman is purposefully made a victim for the “narrative desire to know about the monster.” [14] The demonstration of fear onto the body creates, “ecstatic excess” (Williams 605) and the victimized female body becomes the point of spectacle. Some critics of the subgenre argue that slasher films are “equal opportunity terrifiers” because of the mortality rate of both male and female roles in the films, which can also both be depicted as “caricatures.” [15] While this is true of a fair few films, mainly teen-slasher films such as Scream (1996) and My Bloody Valentine (1981), slasher films generally, “reinforce cultural messages about the virtues of masculinity by presenting a villain who is defectively masculine… and a heroine (the Final Girl) who is more masculine than feminine.” [16] It is femininity that cannot survive in these films.

Sociocultural Influences

Violence related to these sexual differences is the problem of the films as well as a solution for them (Williams 612). Acts of perverse violence function as “cultural problem solving” [17] that reflects upon the anxieties towards sexuality and gender in society, which functions in a similar way that the figure of the femme fatale does in film noir. As a result these particular horrors associated with identity depend on temporal tensions associated with notions of sexuality and gender [18] In other words the misogyny is not unchanging. Therefore the males have control in slasher films and they are often the ones who end the victimization of the female body, [19] which results in extreme male agency over the female body.

Slasher Audiences

Slasher films are often aimed at an adolescent audience, but not fixed on targeting a specifically gendered crowd. [20] This target audience is what arguably resulted in another subgenre of teen-slasher films, to further relate and focus the filmic content to the audience. The sexually violent content of these films results in a constantly changing identification with the victims because of the change in focus from sex to violence. The spectacle creates “sadomasochistic thrills” [21] for the audience while they watch people have sex and then immediately after getting stabbed or hacked with a chainsaw. The identification fluctuates between female powerlessness, the victimized woman, and female power, the final girl [22] as depictions of violence and sex are constantly being placed onto multiple diverse bodies.

Female Roles in Slasher Films

Female Roles: Monster or Victim?

The female roles in slasher films clearly, “suffer simulated torture and mutilation as victims of sadism.” [23] While they are often the victims, they also embody sexual anxieties and conflict within the society, which gives them more allegorically monstrous qualities. [24] Therefore it is the female roles that threaten the patriarchy, sexually liberal or even ambiguous, are often the ones aligned with the monstrous in the film. [25] If the female character is not ready for the attack of the monster or killer, a situation often depicted sexually, then they will inevitably die. [26] The “sexual saturation” (Williams 605) of the female body still functions as a sadomasochistic spectacle for the audience, but it is this combined terror and personification of anxieties that causes the female to be aligned with the monsters, or killers in these films. [27] Both the monster and the female persona must share the same fate and suffer a form of pain or loss, usually death. [28] These portrayals create a “gender fantasy marked by prolonged desire and lack of fixed position with regards to the objects and events being fantasized.” [29]

The Final Girl

It is the non-sexually active and more often virgin girls, the ones that the heterosexual patriarchal society that the films operate in accordance with deems as good, that survive. These women are referred to as “final girls” and are allowed to live to fulfill their function in the aforementioned society. They are often allowed to survive by use of weaponry, often phallic in form, but the sexuality deviates from the object and the sense of pleasure that was derived from it’s use in the hands of the male monster is lost. [30] Some critics argue that both male and female audience members are encouraged to identify with the final girl, [31] but it is arguable that the final girl does not function to serve as solid hope for female viewers. Rather the surviving final girl, much as the death of the female victim, acts as a “symbol of castration” [32] for the male viewer and instates a warning to male viewership about their own actions within society.

Remakes and Resurgence of the Slasher Genre

Contemporary Slasher

It is arguable that recent remakes of horror films are “empty of everything but spectacle” [33] and that new horror films still focus heavily on the horrors of sexual desire and their political connotations. [34] The conventions trace back to Psycho, which lead to “a more sexually explicit tortured and terrorized woman” and Jami Lee Curtis in Halloween is a contemporary version of this. [35] Similar films, such as Friday the 13th, are also explicitly sexually violent depictions. Not much backstory is given about the characters in the film, but it is made clear that whenever the teenagers sneak off to go have sex or partake in other illicit activities that they are either tortured or killed by Jason. The exploitative qualities of the films towards their characters to progress the narrative are still apparent. [36]

Remakes

Within the past 10 years there has been a flux in slasher remakes, Halloween in 2007, Prom Night in 2008, Friday the 13th in 2009, and My Bloody Valentine 3D in 2009, to name a few. The films generally kept the stories the same from the originals, but they were able to utilize new technologies to increase the grossness of the slasher genre. The filming of My Bloody Valentine in 3D is an extreme example of this attempt to assault the audience with sexually violent images.

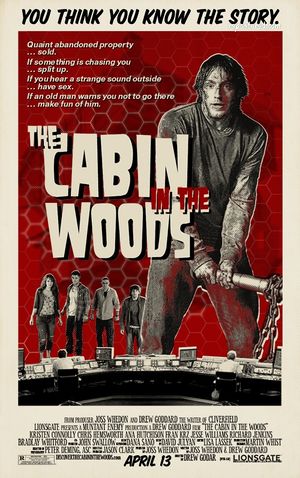

Second Wave of Slasher?

In 2012 the film Cabin in the Woods was released and depicts what is arguably a parody of slasher film conventions including narrative and stylistic techniques. Characters die because of their sexual promiscuity and activity, there are multiple monsters, and there is a higher power at work controlling the microcosmic society of the cabin and the surrounding land. The ending of the film is different from the classic structure because virgin female character, Dana, is not the only one to survive. She does not end up killing the monsters plaguing the area, or her male companion, Marty. This plot twist of mutual survival challenges the ideas that the virgin must be the only one to survive if she is to at all, as well as the societal ideologies of purity, as all of the monsters are set free to rampage upon the world. This address to slasher films raises the question if there is still a place for the slasher genre in our society, or is this obvious parody a sign that the film industry is growing?

Women in Contemporary Horror

In recent years female horror fans and filmmakers have been trying to take back the genre. The female filmmakers attempt to adapt narrative tropes to benefit a feminist story, which scholars refer to as a “reactionary method” [37] of filmmaking. Female horror fans choose to have an alternative reading of the genre as well as a refusal to look, or partake in the gaze that the spectacle invites, which can also be equated with an act of resistance to the “socially expected reaction that the genre reinforces.” [38] These efforts are not easily made, as there is still not a large market in the industry for female made horror films. [39] A group directed to women participating in the horror genre within the industry, Women In Horror, [40] has a mission statement that claims to, “educate and assist women working in the industry and break down the discriminatory treatment of the female gender in genre specific filmmaking.” [41] The group’s aims to heighten and improve female representation within the horror genre are carried out by film festivals, blogs, and workshops. They are stationed in Japan, the USA, and Australia. They are currently a grassroots initiative working to get non-profit status.

Positive Portrayals of Women in Contemporary Horror

Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill One example of a contemporary horror film that demonstrates the feminist movement to take back the genre is the powerful and redeeming portrayal of the character Beatrix Kiddo from Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol 1 and Vol 2 films. Beatrix Kiddo rejects the male gaze by partaking in a "rape revenge" themed plot that aims to take back her power by setting out to seek vengeance on those that wronged her. She refuses to be a passive and hyper-sexualized object of male desire, and is portrayed throughout the film as strong, independent, merciless and a highly skilled samurai sword fighter. She is the ultimate rejection of the victim found in traditional horror and slasher films and represents the modern movement for a more feminist representation of the genre.

The Descent, a British film released in 2005, also incorporates feminist elements. It features a female-exclusive cast, and the first half of the movie places a strong emphasis on the positive platonic relationships between the women. Interestingly, the film never caters to the heterosexual male gaze. The Descent goes on further to defy traditional horror gender conventions through its unique characterization. The women are shown to be strong and resourceful in defending themselves. However, their characters do not fit either of the “tomboy” or “teenaged sex fiend” or virginal “final girl” tropes. Instead, the film opts for a more realistic and nuanced interpretation of its characters.

Scream Queens, while not a horror film, also features positive portrayals of women. The horror-comedy TV series, which aired in 2015, aimed to satirize the genre. As a show geared towards a female audience, it features primarily female protagonists who are rarely sexualized. Many characters often reference or engage in sexual activities, but unlike traditional horror movies, their promiscuity is never penalized. While it features gratuitously gory murder scenes, Scream Queens never engages in the explicit eroticized violence levied against women in typical slasher films. The TV series also directly addresses modern feminist issues—for example, the cafeteria scene from the fourth episode criticizes the objectification of women.

See Also

References

Notes

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Modleski 2009, p.619.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 628.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 629.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 628.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 603.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 613.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 638.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 628.

- ↑ Billson 2014.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 640.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 616.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 615.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 629.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 605.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 609.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 610.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 609.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 629.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 614.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 606.

- ↑ Freeland 2009, p. 629.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 612.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 610.

- ↑ Billson 2014

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 615.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ Grant 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Williams 2009, p. 606.

- ↑ Modleski 2009, p. 623.

- ↑ Michaud 2014.

- ↑ Michaud 2014.

- ↑ Michaud 2014.

- ↑ Women in Horror Month.

- ↑ Women in Horror Month.

Bibliography

- Billson, Anne. “Horror: the film genre where men don’t have all the fun.” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited., 31 Oct. 2014. Web. 10 October 2015.

- Freeland, Cynthia A. “Feminist Frameworks for Horror Films.” Film Theory and Criticism. Ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 627-647. Print.

- Grant, Barry Keith. “Children of the Day: Sex, Gender, and the New Horror Film.” Studies on Themes and Motifs in Literature, Vol 88: Beauty and the Abject: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Ed. Leslie Boldt-Irons, Corrado Federici, Ernesto Virgulti. New York: Peter Land Publishing, 2007. 3-16. Print.

- Michaud, Maude. “Horror Grrrls: Feminist Horror Filmmakers and Agency.” Off Screen: The Experience of Cinema 18.6-7 (July 2014). n. pag. Web. July 2014.

- Modleski, Tania. “The Terror of Pleasure: The Contemporary Horror Film and Postmodern Theory.” Film Theory and Criticism. Ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 617-626. Print.

- Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Film Theory and Criticism. Ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 602-616. Print

- Women in Horror Month. Women in Horror Month. Web. 10 October 2015.