GRSJ224/WomenInHockey

Introduction

The name “hockey” came from the French word “hoquet” which refers to the shape of the hockey stick. The exact origins of the game is unknown, however Montreal Canada, Windsor Nova Scotia, and Kingston Ontario have all claimed to be where hockey originated [1]. The first recorded game between two women’s teams was in Ottawa in 1891 [2].

The National Hockey League is the highest level of competition for professional hockey players, however the league only has male players. The world of sports continues to be identified as male dominant [3][2]. There are plenty of women who have tried to play on male ice hockey teams including Abigail Hoffman, Justine Blainey, Manon Rheaume, and Hayley Wickenheiser [3]. Ice Hockey is an example of a sport with a strong association to the male identity which differentiates between male and female athletes. Men's Ice Hockey has been described with words like 'explosive', 'strength', 'aggressive', and 'body contact' while Women's Ice Hockey has been deemed inferior as it is not as physical and requires more protective equipment [4] [2]. Women's hockey has also been portrayed as a game with high speed, finesse, and play-making [2][5]. The question of whether female athletes should remain in a female-only league versus being able to compete in men's leagues is commonly asked. Those who are opposed to females participating argue that the sport models should be built around being less violent which allows for the empowerment of female athletes, while the supporters for women in men's leagues argue that women's presence as challenging the binaries of femininity and masculinity [3][4].

Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

Sex, gender, and sexuality are socially constructed phenomena, where sex is classified as being one of two categories: male or female. Historically, women were excluded from sports coinciding with the perception that they are fragile and weak [3]. Cultural conceptions of femininity and beauty made women sports even more problematic.

Identity

Female athletes constructed their heterosexual identities through the comparison of homosexual temmates [3]. The experiences of female ice hockey players reveal information on how females come to negotiate binaries of gender which is created through sport and how these ultimately shape the female athlete [3]. The Ontario Women's Hockey Association (OWHA) provides opportunities for girls and women of all abilities to play hockey. A separate girls' hockey association was needed as parents wanted their daughters to have an opportunity to play hockey with a collective identity [6]. Some girls play in boys' hockey programs at a young age as size and differences are not that important to the game yet; generally occurs where a girls' program is limited or absent [5]. The challenge for women's hockey is to define the models of sport that resist the problems of the dominant model of men's sport including violence associated with aggressive physicality while having satisfaction and a sense of empowerment.

Description of Female and Male Hockey Players

Women were allowed in certain sports during the 1880's. Their entrance was guided by the "knowledge" of medicine at the time, which stated that "high intensity" sports should be avoided [2]. They were supposed to choose sports where a toned, slender body was necessary or where sport was a tool to shape or tone the body. Men were supposed to engage in more physical powered sports and endurance. Over time, women began participating in more sports.

The rules of hockey have been adjusted so that there is limited body contact and the requirement of full-facial protection for female hockey players, creating the perception that women are physically inferior and must be protected from physical contact [2][4]. Male hockey players are allowed to full-face cages, half visors, or no visors depending on the age and league. The general appearance of a female ice hockey player was described as masculine. A "female ice hockey player" is not the same as an "ice hockey player" as it produces images of strong men [2]. Women were described as emotional and less ambitious, while men were more like machines.

The Challenge of Gender

DiCarlo conducted a test among 7 female ice hockey athletes and found that the majority of them joined male house leagues between ages 6-8 before joining female rep teams between ages 12-14 due to the inability of "keeping up" with the male physicality [3]. Adolescence is a particular stage where youth struggle with gender and sexuality. The female athletes noted that they were treated differently in terms of physical contact and aggression. Female frailty had a big influence on athlete experiences. In some cases they were treated like "babies" as coaches were easier on the girls and did not yell at them as much [3]. Competitive sports is an important factor for the reproduction and expression of gender. Players describe that they like hockey because it is a physical sport and love to exert physical power to the limit. Women do not want to be seen as ultra-feminine, unpractical with long nails, high heels and sensitive to criticism [2]. Some female athletes classified themselves as "tomboys" so that they can be seen as more aggressive as they surround themselves in a male sporting community [3]. All players want body checking part of the game. They view that limitation as an obstacle from being regarded as actual hockey.

Media Framing

Framing is a way for the media to classify information in ways to communicate to the viewer. Media attention is important for the development of women's ice hockey. In a case study with the Las Fumes High School girl's field hockey team, media attention has been shown to built confidence among team members [7]. They received local media attention in the forms of newspapers and televised coverage. The Olympics is the largest mediated sporting event in the world which allows the media to portray different norms about gender, nationality, and identity. The symbolic relationship between media and sport has been nicknamed the sports-media complex [4].

Sports commentators construct and frame women hockey players differently compared to male hockey players in terms of gender and nationality. The sports media complex views men as natural to the sport while females are viewed as intruders to the male realm [4]. The Media has traditionally "hypersexualized" women to make them more feminine and dependent on men [4]. Televised sporting events frame women athletes as inferior, emotional, and dependent while framing men as superior and independent, however a newer finding shows that women are being framed as athletically fit and more feminine [4]. Some sports have been framed as gender-appropriate: being suited for men and women. Graceful sports such as figure skating or gymnastics are more appropriate for women as it fits the socially accepted images of female behaviour and gain more coverage than physical female sports.

Symbolic, Structural, and Individual Levels

Harding considered dividing society into three levels:

i) Symbolic

ii) Structural

iii) Individual

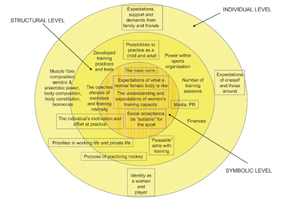

According to Harding, the symbolic level is a set of images and qualities we associate with certain objects or people, the structural level is the power and social structures that affect the distribution of resources and privileges for both sexes and the individual level is where socialization and personal experiences affect how men and women form their identity [8].

For example: At the symbolic level, we see that men's hockey is the "real version" of the game and women's hockey is a "lesser version" of the sport as the rules have been changed. At the structural level, we see the differences in practice time, team finances, and team organization. Men's hockey generally receive more sponsorships and higher pay than women's hockey [2]. At the individual level, we would see feelings of empowerment of the female athlete or reinforced masculinity.

Gilenstam created a visual representation of the three societal levels proposed by Harding which includes psychological and sociological perspectives.

Works Cited

- ↑ Marsh, James H. “Ice Hockey.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published 21 July 2013. Updated 4 Mar 2015. Web. Accessed 15 July 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Gilenstam, K et. al. “Gender in ice hockey: women in a male territory.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 2007. 18:1 235-249. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 DiCarlo, Danielle. “Playing like a girl? The negotiation of gender and sexual identity among female ice hockey athletes on male teams.” Sport in Society 2016. 19:8-9 1363-1373. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Poniatowski, Kelly. “The Nail Polish underneath the Hockey Gloves.” Journal of Sports Media 2014. 9:1 23-44. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Theberge, Nancy. “No Fear Comes Adolescent Girls, Ice Hockey, and the Embodiment of Gender.” Youth and Society 2003. 34:4 497-516. Print.

- ↑ Stevens, Julie et. al. “Together we can make it better: Collective action and governance in a girls’ ice hockey association.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 2012. 48:6 658-672. Print.

- ↑ Heeren, John W. et. al. “Constructing Values on a Girls High School Field Hockey Team.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 2001. 25:4 417-429. Print.

- ↑ Harding, Sandra. The Science question in feminism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986.