GRSJ224/SexualAssaultonCampus

Adrienne Lui (#48923122)

Media representation of Sexual Assault on Campus during the Second Wave Feminism Movement

Introduction

Sexual violence occurs in all cultures and has been represented in various ways throughout the 20th century. Today, our criminal justice system struggles to take control of these crimes, especially on the grounds of college campuses. During the 1970s in North America, social attitudes towards rape and sexual violence on campus began to change considerably in response to social changes, such as the second wave feminist movement. Campuses responded and evolved along with these changes in the 60s to the 70s. The student newspaper was one of the most important historical source of information, “it can be viewed as a “construction of reality” produced interactively by editors, reporters, advertisers, and readers”.[1] It became a platform that reflects the student body’s assumptions, values, and norms. Moreover, we can see the how sexual assault was represented in the media through these types of publications.

Before 1970, findings have suggested that students have refrained from speaking about sex or sexual assault, even though the second-wave feminism movement was in full swing. However, throughout 1970 to 1978, a variety of responses towards these topics quickly emerged, especially within the campus community, like UBC, despite the controversy. Rape relief centres were “urged for campus” to support victims, whilst victims were ironically told to not “write much about the issue”.[2] Sparked by the all the controversy and the male-dominated community in college campuses, women spoke up about single women’s sexual freedom, the objectification of single women’s bodies and rape through media. During the peak of the second-wave feminism movement, with the significant increase of women in the student body and the emergence of the sexual revolution, this period of change has catalyzed the expression of various opinions about the topic of sexual assault in media.

Women in the 1970s

During the 1970s, it was evident that women played an important role in the western society’s economy. However, findings have shown that women were working in lower ranking jobs compared to men.[3] Working women constituted 35 percent in the clerical sector, compared to 8 percent of men.[4] Although there was much growth in the number of women in the workforce, most were part-time roles, indicating that full-time work was still perceived as taboo for women. Most women with college-educated degrees worked in the “clerical or sales sector or traditional professional jobs such as a nurse, school teacher, librarian or social worker”.[5] These changes have catalyzed interest in research about womanhood in the female community, especially in the academic field. With the growing escalation of research about womanhood published by women, there was a stronger understanding of gender equality and women’s rights in the feminist community and the general public.

It is evident that this was a very important time for researchers as more important findings emerged quickly. Women were very vulnerable to sexual abuse in the workplace during the 1970s. During 1976, a survey regarding workplace harassment was published; findings have shown that more

than 70 percent report harassment in the workplace. Moreover, many women took legal action in response to sexual harassment or consequences led by the refusal of sexual demands from male superiors.[7] It is evident that there was much irony in the situation as women participation in the workforce continued to increase. The definition of women was evolving, but yet, those who desired to work instead of staying home on their own accord remained inferior to men. This momentous time has led feminists to speak louder; promoting awareness that workplace sexual assault is a severe social issue. Sexual harassment “was literally unspeakable, which made generalized shared, and social definition of it inaccessible”.[8] The ambiguity of the definition was an obstacle to feminists and victims to take legal action against inappropriate behaviours they were not able to label.

Sexual Assault on Campus during the 70s

Not only was sexual assault an enormous issue in the workspace in the 1970s, but female students on college campuses have also, later, reported inappropriate instructor-student relationships regarding meeting demands of male teachers for higher grades. Male teachers had “the authority to evaluate the performance of female students and, accordingly, the opportunity to affect that performance by initiating sexual demands or behaviours”.[9] Eventually, The Association of American Colleges’ Project on the Status and Education of Women (1978), categorized campus sexual harassment as a serious and widespread “hidden issue”.[10] This awareness was instrumental to the establishment of societies, such as the “Women Against Rape” group. Such societies were important in the female community and crucial to those seeking support for their sexual assault experiences, however, Jim Quail a Ubyssey writer in 1977, discussed and critiqued this society’s actions. He writes that their “recent behaviour...betrays a fundamental imbecility” and claims that they discredit “the worthy movement they delude themselves into thinking they serve”.[11] Despite the critiques, it is evident that such groups have ignited awareness and opened up conversations about rape under the extremes of feminist actions deemed controversial to the society.

Second Wave Feminism

Not until the second wave feminist movement emerged in the 1960s that young women, particularly college students in their 20s, have moved on from their identity as traditional housewives to feminism advocates. With offensive posts involving objectification of women’s bodies in campus newspapers, such as the Ubyssey -- posters of naked female in every final autumn issue until 1968 (“Mary Christmas”)[12] and posts in support of prostitution like the one written by Tony Buzan in 1963[13], the UBC female community expressed disgruntlement, refused to stay quiet and joined the movement.

The emergence of radical feminism from 1967 to 1975 was an important period for this movement. Radical feminists began as small “grass-roots” organizations categorized as “consciousness-raising groups” for women to speak about their experiences and learn about the topic. Eventually, they activated the rape crisis movement with the goals to eradicate sexual assault. In 1973, cultural feminism began to take over radical feminism. This group of young feminists focused on creating a separate world for women rather than attempting to change a men’s dominated society. Both categories of feminists possessed opposing values and beliefs but had the same core feminist values with respect to sexual assault. When women began to come together to form alliances, the second wave feminist movement grew stronger and attracted more media attention. This revolution and their collaborative effort to bring awareness to sexual assault and women’s rights have given strength to young women victims to utilize various platforms to fight against men’s sexual authority over women.

Representation of Sexual Assault in the Ubyssey Newspaper

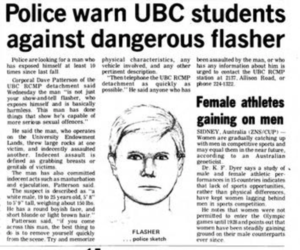

As the sexual revolution progressed through the 70s, students were critiqued for their premarital sexual behaviours and their attitudes towards it. During the birth control debate era, according to an article in the Ubyssey, people who were against it states that it allows “people to indulge their physical desires”, another student stated that if sex was condoned, “the more it will get out of hand”.[14] A few years later, it was evident that the sexual revolution began to take over and spiral out of control; “dangerous flashers” and rapists were recognized and published on the Ubyssey.[15] One warning showed a police sketch of a “white man” with a “round boyish face”, who indecently assaulted victims by “grabbing breasts or genitals”. Reports stated this man performed masturbation and ejaculation in public and is “capable of more serious sexual offences”.[16] The newspaper recognized the value in warning the community about predators and realized that the act of sexual liberation was creating an unsafe campus.

Rape prevention on campus and the recognition of women as vulnerable victims in the Ubyssey has led to the increase of prevention education. Maureen O’hara and Kathy Ford published two articles on the same page critiquing a film titled “How to Say No to a Rapist and Survive”, focusing on methods to avoid victims from being “stupidly visible to a potential victimizers”. [18] These articles were game-changers for the male-dominated style of writing in the Ubyssey. Ford questions the misogynistic messages and refuses to accept the idea that women are to blame for rape. The writer of the film, Storaska’s, glamorized belief that “rape is a crime of sexual passion” was challenged, quoting that “the violence arises from a deep-seated aggression” and is certainly a “crime of violence, humiliation and control”.[19]

Some also critiqued Storaska’s idea that “women have little chance of escaping rape by using self defence or screaming” and will “only anger a potential assailant and cause a violent reaction”, thus by learning self defence “a woman has the advantage of surprise” and potentially receive higher chances of escaping danger.[21] O’hare and Ford had recognized the good intentions in his explanation of this film, however, his method of delivery was questioned and his judgement on rape as a person, who in no way identifies with the victim’s position, was troubling to them.

The Ubyssey has argued against the excuses made for predators and has set a standard for the student body to recognize that sexual assault must not be interpreted lightly. Women in UBC refused to remain silent as staying silent tends to imply agreement and conformity; it appears that they felt a sense of responsibility as women to push back through the Ubyssey platform.

Shortly after the beginning of term 2 in 1978, the fight for “rape centres” appeared 3 times in the same issue.[22] Comparing to the early 70s, this is relatively noteworthy and marks a vital shift of student perspectives towards sexual assault. The Ubyssey quotes a women’s committee spokeswoman saying “rape and assault at UBC shows a serious need for support facilities for victims”.[23]

Despite the overwhelming workload, the Rape Relief agreed to collaborate to offer support, counselling and create a safe space for victims. At the time, victims had “nowhere on campus to go for help”. [24] It is evident that the UBC community was desperate for a supportive place for victims to receive emotional counselling and medical examinations, thus the Ubyssey newspaper had become the platform for students to “scream bloody murder until those proposals (for rape centres) are implemented”.[25]

Concluding thoughts

The paper has evolved from a male-dominated newspaper, to celebrating “Women’s Day” and recognizing that “rape is a very real problem on this campus”.[26] Though female writers still expressed discontent towards the mistreatment of professors with misogynistic beliefs who believed women “lack character to do a man’s work” in certain faculties, the Ubyssey evolved in very drastic ways throughout the 70s.[27] From the disagreement in the student community against birth control, to publicizing an educational article titled “straight talk about condoms, rubbers, sheaths…” .[28] The Ubyssey had liberated the idea of sex, joined in on the rollercoaster of the sexual revolution, struggled to seek a balance between liberation and sexual respect and finally, putting trust into the community to be sexually responsible. In 1978, the paper displays hope and faith in gender equality as the “Alma Mater Society Women’s Centre” began to run workshops, counselling sessions, speakers and more, because, according to Kate Andrew and Fran Watters, “really folks, this is just the beginning.” [29]

References

- ↑ Christabelle Sethna, Creating Postwar Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 290.

- ↑ Unknown, “Rape relief centre urged for campus,” Ubyssey, 17 February 1978, 3,8.

- ↑ Dora L. Costa, “From Mill Town to Board Room: The Rise of Women’s Paid Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14. 4 (2000): 107.

- ↑ Dora L. Costa, “From Mill Town to Board Room: The Rise of Women’s Paid Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14. 4 (2000): 108.

- ↑ Dora L. Costa, “From Mill Town to Board Room: The Rise of Women’s Paid Labor,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14. 4 (2000): 110.

- ↑ Jim Gorman, “Liberated Women,” Ubyssey, 30 October 1970, 19.

- ↑ Catherine MacKinnon, Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination (New Haven and London: Yale University, 1979), 62.

- ↑ Catherine MacKinnon, Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination (New Haven and London: Yale University, 1979), 63.

- ↑ Benson, Donna J., and Gregg E. Thomson. “Sexual Harassment on a University Campus: The Confluence of Authority Relations, Sexual Interest and Gender Stratification,” Social Problems 29. 3 (1982): 237.

- ↑ Benson, Donna J., and Gregg E. Thomson. “Sexual Harassment on a University Campus: The Confluence of Authority Relations, Sexual Interest and Gender Stratification,” Social Problems 29. 3 (1982): 241.

- ↑ Bob Canon, “Chastity ‘outmoded!’,” Ubyssey, 27 January 1961, 1.

- ↑ AJ Birnie, “Untitled,” Ubyssey, 29 November 1968, 4.

- ↑ Tony Buzan, “Whore we to ban prostitution?,” Ubyssey, 17 October 1963, 4.

- ↑ Richard Simeon, “Beware of warping your mentality,” Ubyssey, 19 October 1962, 5.

- ↑ Unknown, “Police warn UBC students against dangerous flasher,” Ubyssey, 20 January 1977, 7.

- ↑ Unknown, “Police warn UBC students against dangerous flasher,” Ubyssey, 20 January 1977, 7.

- ↑ Unknown, “Police warn UBC students against dangerous flasher,” Ubyssey, 20 January 1977, 7.

- ↑ Maureen O’hara, “Rape film harmful, unrealistic,” Ubyssey, 24 February 1977, 5.

- ↑ Kathy Ford, “Vancouver Rape Relief says film advice no help in court,” Ubyssey, 24 February 1977, 5.

- ↑ Unknown, “Rape centre needed now,” Ubyssey, 17 February 1978, 3.

- ↑ Maureen O’hara, “Rape film harmful, unrealistic,” Ubyssey, 24 February 1977, 5.

- ↑ Canadian University Press, “Women urge rape reform,” Ubyssey, 8 November 1977, 1.

- ↑ Unknown, “Rape relief centre urged for campus,” Ubyssey, 17 February 1978, 8.

- ↑ Unknown, “Rape relief centre urged for campus,” Ubyssey, 17 February 1978, 8.

- ↑ Unknown, “Women’s group requests centre for rape victims,” Ubyssey, 17 February 1978, 4.

- ↑ Unknown, “Canada celebrates Women’s day,” Ubyssey, 9 March 1978, 1.

- ↑ Kate Andrew and Fran Watters, “Women work against attitudes,” Ubyssey, 9 March 1978, 5.

- ↑ Julius Schmid, “Julius Schmid would like to give you some straight talk about condoms, rubbers, sheaths, safes, French letters, storkstoppers.,” Ubyssey, 29 September 1978, 15.

- ↑ Kate Andrew and Fran Watters, “Women work against attitudes,” Ubyssey, 9 March 1978, 5.