GRSJ224/Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

One main issue in Canada today is the high numbers of cases of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). Aboriginal women and girls in Canada experience disproportionately high levels of violence, including domestic violence, sexual assault, abduction and murder. Aboriginal women in Canada report rates of violence 3.5 times higher than non-Aboriginal women and, from 1997 to 2000, homicide rates for Aboriginal women were almost seven times higher than that of non-aboriginal women.[1]

These alarmingly high rates of violence and homicide have plagued communities and Aboriginal women for at least 30 years. These high rates, coupled with a lack of inquiry and assistance from the Government of Canada, led to the development of a national Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women campaign. The missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls also include two-spirited, trans-gendered, queer, bisexual and lesbian women, who are often disproportionately impacted from the intersectional discrimination they face. [1]

Background

RCMP reports state that from 1980-2014, there was a total of 1,181 Aboriginal women[2] and girls murdered in Canada, but this was not including suspicious deaths, suspected homicides or cases where women were missing for less than 30 days.[3] Based off these strict criteria, and the high number of suspected, unreported and undocumented cases, many experts, including Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennet, say that “it’s bigger than 1,200; way, way bigger than 1,200.” [4]

The murders are also disproportionately impacting young women – with 55% of cases involving women 31 and younger, and 17% of cases involving girls under the age of 18. [5]The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) has created a database of 582 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women, with nearly half of those remaining unsolved. Nationally, Canada has a clearance rate for homicides of 84% compared to a 53% clearance rate for Aboriginal women and girls. [5]

Another important comparison between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal homicides in Canada is the number of police-reported homicides. Aboriginal female homicides have mostly remained stable, based on the data from 1980-2014, whereas non-Aboriginal female homicide numbers have declined over the years[6].Though Aboriginal women make up only 4.3%.[7] of the national female population, in 1991 Aboriginals accounted for 14% of all female homicide victims, and this number rose in 2014 to 21% [6]

The overwhelming number of missing and murdered Aboriginal women in Canada is very concerning, and under Liberal leadership, the Government of Canada launched a national inquiry to address the issue in December 2015.

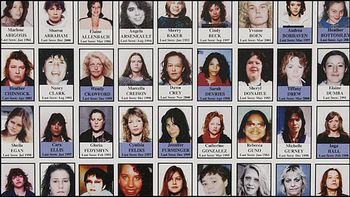

The Women

Of the over 1,181 missing and murdered women, CBC investigated 34 cases where police say foul play was not involved, but where the families of the women refute these findings.[8]. The families of the victims suggest that murder or foul play may be involved.[8]Victims range from as young as 9 months to as old as 83 years in these tragic cases of murdered and missing women across the country[8].

Here are the stories of 3 of these women:

Nadine Machiskinic

Nadine was a 29-year old mother to 4 children who worked in the sex trade and struggled with addictions. She was found severely injured in a hotel in downtown Regina in 2015 and succumbed to her injuries in hospital later that day. She fell 10 storeys down a laundry chute at the hotel, and her family claims foul play was involved in her violent death.[8]

Trudy Gopher

Trudy Gopher was a 19 year old Cree women and mother to a 5 month old baby. Her body was found hanging in a tree in 1997 and police automatically ruled her death a suicide, however her family refutes the suicide ruling.[8]

Alishia (Leah) Germain

Alisha was 15 years old when her body was found off of Highway 16, the Highway of Tears. The 1994 case of her murder has yet to be solved. [8]

British Columbia

From 1980-2012, British Columbia was home to the highest proportion, 20%, of solved and unsolved murders of aboriginal women in Canada, despite its relatively small share of both Canada’s population and the Indigenous Population of Canada. [9]

Highway of Tears

The highway of tears is a 724 kilometer section of Highway 16 by Prince George, BC that gets its name from the high numbers of Aboriginal women who went missing or were found murdered along the highway. There is debate over exactly how many women have gone missing, but many northerners believe it to be more than 30 women—the majority of which have been Aboriginal.[10] Project E-PANA, the RCMP investigation into the Highway of Tears murders, began in 2005. Two years later, the investigation was expanded to include 18 women and an area of 1500 kilometres, adding areas of Highway 97 and Highway 5. [10]

Robert Pickton (serial killer)

With many women disappearing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, police began investigating Robert Pickton as a suspect [9]. Pickton was charged with 27 counts of first-degree murder and was found guilty of 6 counts of second degree murder in 2007, but confessed to killing 49 women[11] at his pig farm in Port Coquitlam, BC.

The victims were also facing bias and abuse, as they were mostly poor, Aboriginal women -- many with drug addiction issues. This bias was evident in the police’s response to their disappearances, where police identified them “as transient drug addicts who weren’t in any trouble or were simply on vacation”[12] Police and prosecution error resulted in the disappearance of at least 19 women, who disappeared after prosecutors stayed a case and released Pickton after he attacked a sex worker at his farm in 1997 and was charged with attempted murder. [12]

Criticism of Government and Police Response

The high levels of violence against Indigenous women highlights the need to examine historic issues of colonialism, residential schools, poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, and racism. Investigation into these issues is necessary to improve the way that police deal with these homicide and missing-person cases.[13] Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennet sympathizes with this notion, discussing the uneven application of justice in cases regrading Aboriginal Women.[14] Racism and sexism are prevalent in cases regarding these women, with police failing to investigate cases and often ruling them as accidental or suicides. [14]

Activism and Organizations

REDress project

The REDress project, created by Jamie Black, is an art installation responding to the missing and murdered Aboriginal women in Canada. The project has collected 600 red dresses that for display around the country to visually represent the absence of these women.[15]

Women’s Memorial March Downtown EastSide (DTES)

This annual, valentines-day memorial march began in 1992 to honour the lives of missing and murdered women.[16] The march is organized by DTES women who gather to stand up against the violence, to remember the lives of their lost sisters, and to create awareness.

Am I Next

The Am I Next campaign is an online effort to create awareness and draw attention to the MMIW crisis. The campaign involved Aboriginal women posting photos of themselves, often in the form of a Facebook profile picture, holding signs reading “Am I next?” and asking their friends to do the same.

International Involvement

UN Human Rights Committee

The United Nations Committee on Human Rights investigated and released a report in 2015 on the Canadian government’s failure to act on the MMIW in Canada. The committee heard from over 26 different non-government human rights organizations on the issue, and requested there be a national inquiry into the disproportionate violence, homicides and disappearances of Indigenous Women in Canada. [17]

#MMIW

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women acronym, MMIW, was also turned into an internationally-recognized hashtag -- #MMIW. In an effort to gain international awareness and support of the issue in Canada, people are now using this hashtag in conjunction with activism and posts on twitter and social media.

Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA)

The FAFIA and the Native Women’s Association of Canada have been working to bring the human rights violations surrounding the MMIW to the international stage. FAFIA’s Campaign of Solidarity with Aboriginal women works to create this international awareness and pressure in their effort to bring an end to the disappearances and murders.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

The National Inquiry was established by the Liberal government in September 2016 in response to calls for action regarding the high numbers of MMIW. Victims’ families, the public, non-government organizations and international organizations all pressured the Government of Canada to launch this independent investigation. The National Inquiry is independent from Federal and Provincial governments and the Crown and is made up of 5 Commissioners, who are mandated to investigate and report on the causes, patterns and factors of violence against Indigenous women and girls [1]. The Inquiry has plans to conduct 9 hearings in the fall of 2017 to hear testimony from families and communities in an effort to gather the truth.[18]

Conservative Leadership

Under Stephen Harper’s Conservative Government, there was no inquiry into the National issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. In fact, there was public outrage at the comments Harper and his Government did make in regard to the issue. One then-cabinet minister even suggested that the violence against Indigenous women was due to a lack of respect among Indigenous men. [13] Stephen Harper was even infamously quoted as saying that “missing and murdered Indigenous women are not on our radar to be frank,"[11] this ignorance and lack of attention causing backlash in media and among Indigenous peoples.

Liberal Leadership and Beginning of Inquiry

One of the running campaigns of Justin Trudeau in the last Canadian federal election, and one of the promises of the Liberal government, was a commitment to launch an inquiry by the summer of 2016.[13] The Inquiry was announced by the liberal Federal Government of Canada in December 2015, and was launched in September 2016. The commission of the inquiry was allocated $53.86 million by the Government, to be used over two years before the mandated completion in December 2018.[19]

Controversy Over the Inquiry Today

The Canadian public, in particular families of the victims, have been criticizing the Inquiry in its delays, ineffectiveness and lack of support. Notably, there has been a very high turnover of commissioners and support staff, which is probing families to wonder why so many qualified staff are leaving the inquiry.[20] Initial public hearings in the pre-inquiry consolations created much confusion, with a few public hearings being held May 30-June 2 before further testimonies were delayed until the fall.

Families and communities have to “hurry up and wait”,[21] causing strife and complaints from families, many who have been waiting for years for an inquiry and answers regarding their loved ones. Beyond this, families of victims have also been identifying a lack of emotional and cultural support from the Inquiry in the investigations of the murders and abductions of their loved ones. [21]Some of the main, critical issues with the Inquiry were identified in an open letter to the Chief Commissioner Marion Buller on May 15th.

The issues include:

- A lack of respect for their culture by inconsistently following Indigenous ceremonial protocols[21].

- The need for an extension to the inquiry's timeframe[21].

- The need for new leadership from "recognized and respected Indigenous grassroots experts across the country"[21].

- The "continued delays, silence, miscommunication, confusion, repeated cancellations..."[21].

- A lack of access for families to lawyers and to traditional healing supports[21].

- Questions about the involvement of the Privy Council Office in the inquiry[21].

- The need for a clear communications plan and strategy relayed to families[21].

- A lack of clarity around legal standing at the inquiry and an extension to the deadline for applying to standing, which has now passed [21].

- The need for a clearly published schedule of events and locations [21].

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 [ "Background — National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls." National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. N.p., 2017. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/en/about-us/background/ ]

- ↑ [ Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. "Background on the inquiry." Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada, 22 Apr. 2016. Web. 20 July 2017. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1449240606362/1449240634871]

- ↑ [ Walker, Connie. "5 cases not included in the RCMP's tally of missing and murdered indigenous women." CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 19 Feb. 2016. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/mmiw-5-cases-to-know-1.3452021 ]

- ↑ [ Tasker, John Paul. "Indigenous families call police investigations inadequate as pre-inquiry talks wrap up." CBCnews. The Canadian Press, 17 Feb. 2016. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/mmiw-inquiry-police-1.3448759 ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 [ "Fact Sheet Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women and Girls." Native Women's Association of Canada. Native Women's Association of Canada, May 2015. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.nwac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Fact_Sheet_Missing_and_Murdered_Aboriginal_Women_and_Girls.pdf ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 [ Miladinovic, Zoran, and Leah Mulligan. "Homicide in Canada, 2014." Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. N.p., 30 Nov. 2015. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2015001/article/14244-eng.htm#a14 ]

- ↑ [ Milan, Anne. "Female population." Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. N.p., 03 Mar. 2016. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14152-eng.htm ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 [ "Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women." CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, n.d. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/missingandmurdered/ ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 [ Culbert, Lori. "Many missing, murdered aboriginal women from B.C." The Vancouver Sun. N.p., 11 Mar. 2015. Web. 23 July 2017. http://www.vancouversun.com/news/many_missing_murdered_aboriginal_women_from/11490141/story.html ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 [ "Highway of Tears Background." Highway of Tears. Carrier Sekani Family Services, n.d. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.highwayoftears.ca/about-us/highway-of-tears ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 [ Sterritt, Angela. "A Movement Rises." OpenCanada. Centre for International Governance Innovation, 20 Nov. 2015. Web. 11 Aug. 2017. https://www.opencanada.org/features/movement-rises/ ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 [ Keller, James. "Bias against Pickton's victims led to police failures, indifference." Macleans. N.p., 05 Feb. 2014. Web. 29 July 2017. http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/bias-against-picktons-victims-led-to-police-failures-indifference-inquiry/ ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 [ Blaze Baum, Katherine, and Matthew McClearn. "Prime target: How serial killers prey on indigenous women." The Globe and Mail. N.p., 24 Aug. 2016. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/prime-targets-serial-killers-and-indigenous-women/article27435090/ ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 [ Baum, Kathryn Blaze. "Justice 'uneven' in cases of missing, murdered indigenous women: minister." The Globe and Mail. N.p., 24 Mar. 2017. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/justice-uneven-in-cases-of-missing-murdered-indigenous-women-minister/article29564098/?ref=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.theglobeandmail.com& ]

- ↑ [ Jaime, Black. "About The REDress Project." The REDress Project. N.p., 2014. Web. 29 July 2017. <http://www.redressproject.org/?page_id=27>. ]

- ↑ [ "About - Womens Memorial March." Feb 14th Annual Womens Memorial March. WordPress, 13 Feb. 2017. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. https://womensmemorialmarch.wordpress.com/about/ ]

- ↑ [ The Early Edition. "First Nations poet welcomes the UN's calls into missing and murdered aboriginal women inquiry." CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 23 July 2015. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/un-s-calls-for-inquiry-into-missing-murdered-aboriginal-women-welcomed-by-first-nations-poet-and-activist-1.3165608 ]

- ↑ [ Fontaine, Tim. "First public hearings for MMIW Inquiry to begin in Whitehorse." CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 30 May 2017. Web. 29 July 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/mmiwg-whitehorse-hearings-underway-1.4135906 ]

- ↑ [ "About the independent inquiry." Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada, 11 Oct. 2016. Web. 5 Aug. 2017. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1470140972428/1470141043933#chp5 ]

- ↑ [ News, CBC. "'It needs a restart': Manitoba chief calls on MMIW inquiry head to resign." CBCnews. Ed. Chris Read. CBC/Radio Canada, 04 July 2017. Web. 5 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/mmiw-chief-commissioner-call-for-resignation-1.4189047 ]

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 [ Porter, Jody. "'How do you expect families to do all that work?' family member asks MMIW inquiry." CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 16 May 2017. Web. 1 Aug. 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/missing-murdered-inquiry-delay-1.4116335 ]