GRSJ224/Korean Comfort Women Issues and Their Conflict with Japanese Government

Korean comfort women (위안부) were forced military sex slaveries during imperial Japanese military occupation in World War II.The imperial Japanese army kidnapped young Korean women from their homes by luring with promises of work in factories or restaurants. During the Japanese occupation in Korea in early twentieth century, the Japanese military commenced to recruit single, young and healthy women for military purposes. [1]Although this wiki page only focuses on Korean comfort women, it is important to know that "the "comfort women" commonly used to describe the approximately 400, 000 Asian women who were conscripted into sexual slavery" by the Japanese army during Asian and Pacific War from 1931 to 1924 (p.339). Roughly around 160,000 of these comfort women had Korean nationality. The comfort women were constantly raped by Japanese soldiers from 10 to 30 times a day and they were regularly beaten and tortured by the army. Therefore, many women often died of venereal disease or other injuries and many of them committed suicide at the comfort stations [2]

Spirit's Homecoming (귀향)

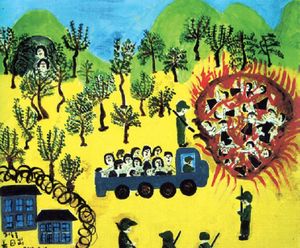

The comfort women issues were not one of the prioritized issues for many Koreans until many television shows and documentaries began to highlight this historical issue a few years ago. As the media emphasized how the imperial Japanese soldiers kidnapped young Korean women for military sex slaveries during World War II and how only a few of them survived from this tragic incident, many Korean citizens became interested in the issue. With a interested crowd, the movie called Spirit's Homecoming (귀향) was finally able to get sponsored to premiered, after being unable to release the movie because of a lack of funding. The movie Spirit’s Homecoming is a South Korean movie that tells a story of Jung-Min, a former Korean comfort woman who returned to Korea end of the war. The movie Spirit’s Homecoming was the inspiration of this wiki page.

History of Korean Comfort Women in World War II

Recruitment Process of Korean Comfort Women

During the period of early twentieth century, Korean women’s desire for work and education during the period of early twentieth century. This influence carried by the emergence of working women, who laboured at factories and in service jobs. The women’s occupation diversified and modernized by the late 1920s in Korea and it became common for the daughters to leave home to achieve the “modern girl” status. Moreover, the Japanese military forced the Korean women to join the comfort women, when the young women were working at the factories. Although it was more common for young women from poor families to get forcedly recruited with a promise of a job by the military, there were also girls from middle-class families, who chose to leave home to escape unhappy, dysfunctional, and oppressive situation and to seek employment in a modern industrializing society. These girls from the middle class families who left home to join the forefront of the industrial revolution as factory workers were called the “runaway daughters.” The runaway daughters were more likely to get kidnapped by the Imperial Japanese army, when they were working at the factories.Furthermore, the Korean young women’s desire to be a literate led them to become Kisaeng (기생), singers and dancers who entertained higher authorities such as the yangbans and kings. Since only literate women in the early twentieth centuries were the daughters from high class or kisengs, many young girls from poor families, who wanted to be able to read and write Korean, became kisaengs. However, the kisaengs also provided sexual services and it was common for kisaengs to get objectified and get purchased by the higher classes, which made it easier for the Japanese army to take them. In addition to young Korean women who desired to get a job or get educated, Korea’s unstable period in early twentieth century contributed to ‘runaway daughters,’ which made easier for the Imperial Japanese army to kidnap the young women. [3]

Most commonly, the Imperial Japanese soldiers forcedly captured comfort women. The deception, coercion and lying were common in the process of recruitment. Also, Korean villages were often raided by the Imperial Japanese army to seize women. Many testimonies tells us how the Imperial Japanese army lured the Korean girls for the promise of getting a job at factories and took the girls to the comfort station. The Japanese military officials tried to recruit the ‘virgin’ women by using their influences on Korean government officials. Especially, the Japanese army demanded on Korean public schools to provide virgin women. While the Imperial soldiers concentrated on recruiting ‘young virgins’ in the poor and uneducated part of Korea, Ewha Women’s university students were extremely frightened when many students began to quit school in order to get married in a hurry to avoid getting kidnap by the soldiers. The school officials announced to all the students that the school will take full responsibility to protect them to prevent a mass exit of students. However, not long after the announcement, the school signed a document with the Imperial soldiers that the university will cooperate to mobilize human resources for the war. Therefore, there was no safe space for young women in Korea during this period. [4]

Living Condition at the Comfort Stations

There were two types of comfort stations: the concessionary military comfort facilities and paramilitary comfort facilities. Depending on the type of comfort stations, the living conditions differed. First, the concessionary military comfort facilities were operated by civilians in urban area and served high ranking officials with privileges. Since the comfort women had to provide sexual service to the high ranking officials, the owners of the comfort station stipulated a weekly medical examination of the females receptionists. [5]Moreover, as upscale modern military recreational facilities, the residential areas were given to the comfort women. Each comfort women were provided by a separate room with its own bathroom and it was simple but clean. All the comfort women resided in the concessionary comfort stations were kisengs or educated women. Compared to the concessionary comfort stations, the paramilitary comfort stations were located in a remote frontline area, where the comfort women performed as manual and sexual labour. For the comfort women at the paramilitary comfort stations, there were less comfort women but more imperial soldiers to serve. Therefore, the living condition of the paramilitary comfort stations was drastically poorer than the concessionary comfort stations. Similar to the concessionary comfort stations, the comfort women in the paramilitary comfort stations were also provided with individual’ rooms but it was adjoining room, divided by a curtain. Although the comfort women in paramilitary centres also had medical examinations, the doctor often missed the visit. Moreover, they had no set holidays and had to serve solders even during menstrual periods. The Imperial soldiers unexpectedly visited the comfort women often and, therefore, they barely slept. On top of exhaustion from overworking, the comfort women in paramilitary comfort stations also frequently got beaten by drunk soldiers. The soldiers often demanded that the women entertain them by singing or dancing. [6]

The former Korean comfort women's testimonies from the paramilitary comfort stations shows the hardships of the comfort women. Witnessing the violence in the comfort stations was one of the daily routines and the military officers often threatened to kill the comfort women. Many former Korean comfort women confessed how even when her vagina and uterus felt like they were torn in shreds, the soldiers kept coming in one after another. When war was nearly over, only a few women were left at each comfort stations; therefore, the comfort women at the paramilitary comfort stations had to deal with more soldiers through the vaginal pain. Moreover, many women often got pregnant at the paramilitary comfort stations and many of them also had venereal disease also because of lack of medical care. In the end of their pregnancy, non-medically licensed soldiers operated on these pregnant women. This poor environment at the paramilitary comfort stations killed many comfort women, compared to concessionary military comfort facilities. [7]

Testimonies of Former Korean Comfort Women

In the book Silence Broken by Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, many testimonies of former Korean comfort women can be found. For this part of wiki page, two chapters are shared: chapter one, I would rather die than and chapter eight, If only my father let me go to school. By exploring these two chapters, the readers can visualize the terrifying hardships that the Korean comfort women went through. [8]

Chapter One: I would rather die than from Silence Broken by Dai Sil Kim-Gibson

At the age of twelve, Hwang Keum Ju received a notice called Kunro Jungsindae (Korea Women's Volunteer Labour Corps (조선여자근로정신대)) from the Imperial Japanese soldiers. All the unmarried daughters in the households had to join Jungsindae. They could not make any choice but to join the Jungsindae. For Hwang Keum Ju, she had 100 won that she borrowed from rich neighbour for her dad's medication so she was happy that she would have a chance to pay back the money, if she join the 'labour corps.' She confessed that this initial thought was her biggest mistake. As she joined the Jungsindae, other comfort women and she got on the train and she was placed in northern Manchuria. On the first day, she got to the comfort station, she was terrified and she was very hungry because the Imperial army had not fed her during the train journey. As soon as she got signed to her 'room' that was divided with other 'rooms' with only curtains in between, one of the highest officers came into her room and started to rape her. She tried to pull away from her but the officer dragged her by grabbing her hair and slapped her cheeks. As she yelled, "I would rather die" (p.23) to the officer in Korean, the officer started to kick her in her stomach and raped her. After that traumatic night, she remembered waking up on the ground, where her blood was permeated. She confessed that everyday at the comfort station was repeat of that first day. She thought to herself that she "can't get our of here alive" (p.23). Keum Ju also added that living condition at her comfort stations was very poor. The comfort women at her comfort station were starving all the time because the imperial soldiers barely fed them and even during extreme cold weather, the comfort women barely had clothes to wear. On average, about 30 to 40 soldiers each day came to every woman and on holidays, the numbers increased. "Nothing, nothing stopped them" (p.25). Kim-Gibson, the author of the book, added on the end of Keum Ju's testimony that Keum Ju had to vomit several time, while she recalled this part of history of her life.

Chapter Eight: If only my father let me go to school from Silence Broken by Dai Sil Kim-Gibson

Yun Doo Ri was from a wealthy family as her father owned several lands in Ulsan and her grandfather was a government official of high rank. She confessed that she was always interested in education and she dreamed of being a career woman, when she grow up. Although her family was wealthy, during the war time, the Japanese soldiers confiscated her house and all the belongings that her family had, which made her family homeless. Therefore, Yun Doo Ri started working at a glove manufacturing factory to support her family. One day, on her way to work, she passed police station and police officers captured her without any reason. She strongly protested and yelled "Help!" in Korean and the officers started to kick her in the stomach because she talked in Korean, which made her pass out. When she woke up, she was at the comfort stations. At her age of fifteen, Yun Doo Ri got raped by the high ranking officer at the comfort stations for the first time. She confessed that end of every day, she passed out because of exhaustion. During her menstruation, she requested the soldiers that the soldiers can not visit her because she goes through unbearable pain but she got beat up by the soldiers. One thing that haunted her during her time at the comfort station was that she would not be able to become a career woman that she always dreamed of and she would not be able to marry someone in the future.

Current Issues of Korean Comfort Women

Early Life Trauma of Korean Comfort Women

Many survivors expressed a deep sense of shame and this shame often linked to dishonour for families or survivors. Therefore, many survivors often rejected by their families when they returned home from Korea. Due to the shame of sexual abuse and conservative nature of Korean society during postwar period, the comfort women were kept in secret and many Koreans were unaware of this issue until survivors began speaking out in the 1990s. In 1991, the first survivor shared her former comfort women experience with the public. According to the journal article Korean Survivors of the Japanese "Comfort Women" System: Understanding the Lifelong Consequences of Early Life Trauma by Jee Hoon Park and others, the unbearable pain and hardships that former comfort women went through at the comfort stations have lifelong impact of early life trauma on them. The lifelong impacts are "stressed relationships with men, difficulties in having children, loneliness and depression, physical pain, and continued hardship influenced by their experiences in the comfort women system" (p. 339). Moreover, other comfort women still expressed anger toward the Japanese and expressed a strong desire for an "apology and compensation for their exploitation" (p.340).[9]

Memorials to All the Comfort Women During the WWII are Needed

In South Korea, the several dozen elderly survivors from comfort stations are live symbols of Korea's suffering during its time as a colony of Japan. There are many testimonies confessed by the former Korean comfort women that shows the victimhood of being sexual slaveries to the Imperial Japanese military. As many Korean researchers try to publish their works that established with the former Korean comfort women about the issue, the Japanese governments are busy refusing their involvement in the warcrime.

In late December,2016, a comfort women statue was installed outside the Japanese consulate in Busan, South Korea's second largest city. This statue is similar to other comfort women statues in public places in Korea, but this one was the second put up near a Japanese diplomatic building. The Busan statue is dedicated to the thousands of women who were detained in the Japanese military comfort stations as sex slaves during WWII. As soon as statue has been placed, Japan responded bitterly by saying that Korea violated the 2015 agreement, that the Japanese government 'apologized' to those who suffered as comfort women without acknowledging their legal responsibility of this issue. Moreover, the Japanese government requested to Korean government to remove the statue because it is an object to disgrace Japan, when in fact, the statue is a symbol of acknowledging "human sufferings that we should not and cannot forget."[10]

Unsolved conflict with Japanese Government

The Japanese Government's Refusal to Admit Their Warcrime

The testimony of Professor Yoshimi Yoshiaki explains the suppressed knowledge of the comfort women in Japan. According to Professor Yoshimi Yoshiaki, the Japanese government burned public documents during the two week period between its surrender because those documents might have worked against them in a court-material. Furthermore, the professor explains how Japanese boast about the military comfort women after the war, but the issue was never taken up as a problem of human rights violations. In the end of his confession, he also adds that Japan only talks about half of its history, the half where Japan is victimized. [11] Moreover, currently, Japanese Prime Minster, Shinzo Abe, is trying to whitewash the past by glossing over the past of the comfort women. The Japanese government argues that the comfort women were paid prostitutes, not victims of official military policy.[12]

Postcolonial Feminist Perspective of Korean comfort women

The Korean Women’s Movement of Japanese Military Comfort Women from a Postcolonial Feminist Perspective

The postcolonial feminist perspective, which is the fight against androcentric nationalism and colonialism, is necessary to understand the issue of comfort women as a past event that is continuously effected by the hegemonic power relationships surrounding South Korea’s present postcolonial setting. Before discussing about the Korean women's movement of Japanese military comfort women from a postcolonial feminist perspective, many researchers criticized that Korean and Japanese nationalistic paradigms on the Korean comfort women issues. Since the mid-1990s, Korean feminists, confronted with Korean and Japanese nationalism, sought to produce alternative narratives about comfort women from feminist perspectives. Examining the complex relationship between women and nations, as well as feminism and nationalism, a Korean researcher, Chung argues that issues related to Japanese military sexual slavery relate not only to women but also to the nation and that both are rooted in the colonial context of women’s dual oppression by patriarchy and national relations.[13] On the other hand, another Korean researchers, Yang criticizes the masculine and Japanese-centered focus in representations of Korean comfort women’s issues, and suggests the articulation of viewpoints from personal memories as alternative subjects of analysis and history. [14]

The patriarchal sexual culture of the postcolonial era was an important hidden backdrop for the long period of silence within South Korea. Because Confucian cultural norms were still deeply entrenched in Korean society, unmarried women sexually abused by foreigners were labeled as defiled. The defiled daughter or wife brought shame to her family. According to the former comfort women, they could not return home or had to hide their experiences even from their kin. Furthermore, for Korean people as a nation, a comfort woman symbolized the helplessness and impotence of Korean men who could not protect their own women, families, and nation from their Japanese enemy. "Young Korean virgins, collectively raped by Japan, the colonizer, symbolized the lost nation, lost sovereignty, lost motherland, and consequently lost national pride" (p.75). This historic and traumatic memory, which is deeply embedded in the nation’s subconsciousness, haunted Korean society and resulted in survivors’ lifelong suffering. Therefore, the comfort women' movement, which has persisted through Korea’s dynamic political transition from dictatorship to democracy and state nationalism to globalization, is an example of postcolonial feminist practice. From the outset, the movement has questioned the colonial legacies and androcentric nationalism that doubly oppress colonized women. [15]

Comparison between Korean Comfort Women and Comfort Women from Dutch East Indies

In early December 1941, the Japanese Imperial forces entered the war against the Allied nations and the conquest of the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) was a high priority. Japanese troops committed sexual violence against Dutch women at various places in the Dutch East Indies immediately after the invasion. For example, when they entered Tjepoc, the main oil centre of central Java, “women were repeatedly raped, with the approval of the [Japanese] commanding offirer” ( p.61).There is hardly any official record concerning sexual violence against Indonesian women committed by the Japanese at the time of invasion. Therefore, it is very difficult to speculate how prevalent rape of Indonesian women was by the Japanese troops in various places of the Dutch East Indies, where many Dutch women became the victims of sexual violence.[16]

Jan Ruff-O'Herne, from Adelaide, Australia, kept her traumatic secret of being a comfort woman for 50 years. She was captured at 19 years old by the Japanese Imperial forces in 1942, in the Dutch East Indies, where she had been living a happy colonial existence before she was abducted. She is now asking for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to apologize and offer compensation. She has been campaigning to receive apologize after Prime Minister Abe offered words of regret and millions of dollars for a compensation fund. However, only for the Korean survivors received this compensation. Ms Ruff-O'Herne now wants to know why the same can not be done for her and for other victims from other countries as she said "Women should never be raped in war; rape should not be accepted because it's war." [17]

Reference

- ↑ Soh, Chung-Hee. "Women's Sexual Labor and State in Korean History." Journal of Women's History 15, no. 4 (Winter 2004): 170-77. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1353/jowh.2004.0022.

- ↑ Lee, Constance Youngwon, and Jonathan Crowe. "The Deafening Silence of the Korean “Comfort Women”: A Response Based on Lyotard and Irigaray." Asian Journal of Law and Society 2, no. 02 (2015): 339-56. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1017/als.2015.9.

- ↑ Soh, Chunghee Sarah. The comfort women: sexual violence and postcolonial memory in Korea and Japan. Chicago, Ill.: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2009.

- ↑ Howard, Keith, and Young-joo Lee. True stories of the Korean comfort women: testimonies compiled by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan and the Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. New York: Cassell, 1995.

- ↑ Min, Pyong Gap. "Korean “Comfort Women”." Gender & Society 17, no. 6 (2003): 938-57. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1177/0891243203257584.

- ↑ Soh, C. Sarah. "Aspiring to craft modern gendered selves." Critical Asian Studies 36, no. 2 (2004): 175-98. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1080/14672710410001676025.

- ↑ Gottschall, Jonathan. "Explaining wartime rape." Journal of Sex Research 41, no. 2 (2004): 129-36. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1080/00224490409552221.

- ↑ Kim-Gibson, Dai Sil. Silence broken: Korean comfort women. Parkersburg, I.A.: Mid-Prairie Books, 2000.

- ↑ Park, Jee Hoon, Kyongweon Lee, Michelle D. Hand, Keith A. Anderson, and Tess E. Schleitwiler. "Korean Survivors of the Japanese “Comfort Women” System: Understanding the Lifelong Consequences of Early Life Trauma." Journal of Gerontological Social Work 59, no. 4 (2016): 332-48. Accessed April 4, 2017. doi:10.1080/01634372.2016.1204642.

- ↑ Qiu, Peipei. "Why Korea's comfort women must be remembered." South China Morning Post, January 16, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2017. http://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/2061990/why-koreas-comfort-women-must-be-remembered.

- ↑ Yoshimi, Yoshiaki. Comfort women: sexual slavery in the Japanese military during World War II. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

- ↑ Ripley, Will. "A lifetime later, a Korean 'comfort woman' still seeks redress." CNN, April 29, 2015. Accessed April 4, 2017. http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/29/asia/will-ripley-japan-comfort-women/.

- ↑ Chung, Chin-Sung. 1999. “Minjok mit minjokjuie ganhan hankukyeoseonghakwi nonui.”Journal of Korean Women’s Studies 15 (2): 29-53.

- ↑ Yang, Hyunah. 1997. “Revisiting the Issues of Korean Military Comfort Women.” Positions 5 (1): 51-71.

- ↑ Lee, Na-Young. " e Korean Women’s Movement of Japanese Military “Comfort Women”: Navigating between Nationalism and Feminism." The Review of Korean Studies 17, no. 1 (June 2014): 71-92. Accessed April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Tanaka, Yuki. Japan's Comfort Women. Rutledge, 2003.

- ↑ Carney, John. "'We were there for the sexual pleasure of the Japanese military': Australian woman, 93, raped as a WWII 'comfort woman' demands justice after 70 years." Daily Mail Australia, February 17, 2016. Accessed April 5, 2017. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3450302/Jan-Ruff-O-Herne-93-forced-comfort-woman-WWII-pursuing-Japanese-government-damages.html.