GRSJ224/Gendered Issues in Homelessness

Definitions

Homelessness

The Canadian Homeless Research Network defines homelessness as “the situation of an individual or family without stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it. It is the result of systemic or societal barriers, a lack of affordable and appropriate housing, the individual/household’s financial, mental, cognitive, behavioural or physical challenges, and/or racism and discrimination.”[1]

The organization further divides homelessness into four different typologies. [1]

1. “Unsheltered” refers to those living in the streets or areas not meant for residence.

2. “Emergency sheltered” refers to those taking refuge in homeless or domestic violence shelters.

3. "At risk of homelessness" refers to those at risk of losing their homes.

4. "Provisionally accommodated" are those with temporary housing.

Sex and gender

The American Psychological Association defines sex as a person’s “biological status…typically categorized as male, female, or intersex”, while gender refers to the “attitudes, feelings, and behaviours that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex.” [2]

Men

Demographics

Men make up the vast majority of the homeless population. It is estimated that 73.6% of the homeless are comprised of men.[3] Within Canada, single adult men between 25 and 55 comprise half of the homeless population; the average age of a man in a shelter is 37 years.[3] Ethnic minorities may also be at an increased risk of homelessness. In the United States, 62% of homeless men are from a racial minority.[4]

Causes

Homelessness is caused by a variety of different factors. One of the main factors is the high prevalence of mental health issues. The Canadian Mental Health Association estimates that 25-50% of homeless people have some form of mental illness.[5] Furthermore, 45% of all homeless men have experienced some form of traumatic brain injury.[6]. 87% of these injuries occurred prior to the men becoming homeless, drawing a direct causation link between the participant’s personal mental and physical well-being and homelessness. In addition, a significant number of homeless men have ADHD or hyperactive disorders.[7] These factors make it difficult to succeed in academic and work environments. For example, only 31% of homeless men have attained a Grade 12 education.[7]

Further exacerbating these issues is the subject of substance abuse. In 1991, approximately, 30-40% of homeless people reported some form of alcohol abuse problem, while 10-15% experienced problems with drug abuse.[8] Substance abuse among the homeless is even more prevalent today—a more recent study conducted on homeless men and women in Toronto concluded that 60% regularly used drugs.[9] According to the study, single men were also the demographic most likely to be affected by drug use. Overall, homeless men are significantly more likely than women to have some form of drug, alcohol, or tobacco dependence.[10]

Gender stereotypes also have a role in the gender disproportionality of homelessness. Men may find it difficult to circumvent social barriers in requesting for help. Men who hold “traditional attitudes about the male role, concern about expressing emotions, and concern about expressing affection toward other men were each significantly related to negative attitudes toward seeking professional psychological assistance.”[11] Similarly, single homeless men visit hospital emergency room departments less frequently than their female counterparts do.[12] Homeless men are also more likely to live in isolation, [13] making it more difficult for them to rely on social networks for support. They are also more likely to have antisocial disorders.[14]

Issues

One significant issue is the lack of resources dedicated in addressing the issue of male homelessness. Despite the gender imbalance homelessness, it is rarely thought of as a gendered issue affecting men. However, there is high public awareness of and numerous resources dedicated towards women’s homeless shelters and domestic violence centres. For example, within the Greater Vancouver area, charitable organizations such as the Burnaby Safe House, Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre, and The Bloom Group Women’s Shelter offer services catered specifically towards women. By contrast, there is only one male-exclusive homeless shelter, The Russell Housing Centre,[15] located in New Westminster.

While the homeless population has high mortality rates in general, it appears that men are particularly susceptible to early death. In England, homeless women are thirteen times more likely to die than the average person, while homeless men are seventeen times more likely to die.[16] The main causes of deaths were attributed to drug or alcohol abuse, or cardiovascular and cancer-related diseases. Another cause may be the nature of homelessness amongst men—men report more episodes of homelessness at longer periods of time.[13]

Women

Demographics

Women make up a smaller percentage of the homeless population, at around 26.2%.[3] The Ontario Women’s Health Network conducted a survey on the female-identifying homeless population within Toronto.[17] The women averaged 42 years of age, with ages ranging from 19 to 66. Approximately 16% identified as members of the LGBT community. Moreover, 26% were ethnic minorities, with Aboriginal women comprising the majority.

Causes

Within Canada, 65% of women are homeless due to their inability to pay rent or find income, 25% are homeless due to their inability to find suitable housing while a remaining 33% cite mental or physical health issues.[17] As is the case with men, substance abuse is also a significant factor in homelessness—41% of single homeless women experienced issues with recent drug abuse[9]. Education levels are typically low among this group, with less than half of homeless women having completed their high school degree[17], significantly inhibiting their socioeconomic mobility. In comparison to men, women living on the streets are much more likely to come from a background of sexual abuse, both in childhood and adulthood.[18] Domestic violence is a significant factor in causing homelessness as well. Within the U.S., half of the women cite domestic violence as the reason for their homelessness.[19]

Issues

Homeless women are an extremely vulnerable demographic targeted for physical and sexual abuse. 37% of homeless women reported being physically assaulted within the current year while 21% experienced some form of sexual assault, making them 10 times more likely than men to be sexually assaulted.[17] However, these crimes often remain unreported, and those which are reported are often given unsatisfactory responses by the police.[20]

Homeless women are placed at a higher risk due to inadequate access to proper hygiene facilities and reproductive health resources. Many cannot afford menstrual products, and instead, must rely on charitable donations.[21] Moreover, 42% of sexually active homeless women do not use birth control.[22] This issue, in particular, has led young homeless women to have significantly higher pregnancy rates.[23] Young homeless women have double or quadruple the risk of miscarriage.[24]

Homelessness has a negative impact on both maternal and child health—a study conducted on homeless mothers revealed that 50% were able to offer consistent care to their children while a further 20% report having no contact with their children.[23] The participants within the study were also found to have significant mental health issues, including PTSD, drug abuse, and depression.

Homeless women in particular need “comprehensive services, including pregnancy prevention, family planning, and prenatal and parenting services."[23] Women who did have access to a regular source of birth control services reported lower alcoholism rates, as well as a decrease in the perceived barriers accessing to medical care.[25]

Transgender

Demographics

There is a disproportionately high number of LGBT individuals present in the homeless youth population. Among the homeless youth in British Columbia, 33% of females and 10% of males identify as LGBT.[26] Many become homeless within their adolescent years; in New York, for example, the average age of homelessness for a transgendered person is only 13.5 years.[27]

Causes

There are several factors behind the over-representation of homeless LGBT individuals. One significant factor in driving homelessness is the conflict between transgendered youth and their family. In British Columbia, one-quarter of adolescents are convicted from their homes due to family conflict regarding their sexuality or gender identity.[26] Parental approval and support of gender identity is particularly critical to the mental and physical well-being of transgendered children and teens. Those with strong parental support reported “higher life satisfaction, higher self-esteem, better mental health including less depression and fewer suicide attempts, and adequate housing.” [28]

Conflict with peers may also act as a risk factor for homelessness. A majority of transgendered students, 68%, have experienced verbal harassment due to their gender identity.[29] Transgendered individuals may turn to substance abuse as a coping mechanism. LGBT individuals are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to have a dependence on alcohol or drugs.[30] As a result of all these factors, the suicide attempt rate for this particular demographic is currently at 62%.[31]

As with cisgendered men and women, socioeconomic status has a high impact on the homelessness within the transgender community. Transgendered adults have higher rates of poverty and unemployment.[32] This may be due in part to hostile work environments. A report conducted by the National Center of Transgender Equality indicated that 90% of those surveyed had been harassed or mistreated at work.[33] Even if transgendered individuals do have the resources in place to procure housing, they may still be rejected on the basis of discrimination. 1 in 5 transgendered individuals have been denied housing due to their gender identity.[26]

Issues

Compared to their heterosexual counterparts, homeless LGBT individuals experience significantly higher rates of physical and sexual assault. For example, 58% of LGBT youths have been sexually assaulted compared to 33% for heterosexual youths.[34] Gay or transgendered young adults also engage in survival sex at higher rates.[26]

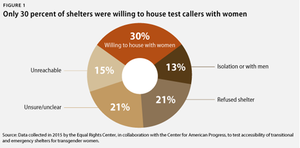

Gender identity may also be problematic, chiefly when it comes to gender-segregated homeless shelters. According to the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 1 in 3 transgendered youth experience rejection from a homeless shelter on the basis of their gender identity.[31] In particular, transgendered women experience discrimination when accessing women’s shelters. A study conducted by the Centre for American Progress and the Equal Rights Centre contacted homeless shelters in four American states to determine the level of receptivity shelters would have towards housing transgendered women.[35]. Only 30% of the homeless shelters indicated a willingness to accommodate transgendered women with other women. Moreover, some shelters accept transgendered women only if they have received sex reassignment surgery, which is often not a viable option is given the costliness and invasive nature of the procedure.[36]

Similarly, individuals who have transitioned from female to male tend to avoid homeless shelters in favour of staying on the streets or couch surfing.[28] Reasons cited in the report include “fears of violence when staying in men’s shelters” as well as the “fears that their male identity and personal dignity would be judged and ridiculed in women’s shelters.” Among the transgendered homeless community as a whole, 22% have been assaulted by shelter staff or other residents.[26]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.cagh.ca/site/index.php/our-group/homelessness-defined

- ↑ https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/sexuality-definitions.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SOHC2103.pdf

- ↑ https://www.huduser.gov/Publications/pdf/2009_homeless_508.pdf

- ↑ https://www.cmha.ca/public_policy/out-of-the-shadows-forever-annual-report-2008-2009/

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140425104714.htm

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.covenanthousetoronto.ca/homeless-youth/facts-and-stats

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1772151

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-10-94

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/thinking-man/11787304/Homelessness-is-a-gendered-issue-and-it-mostly-impacts-men.html

- ↑ http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/cou/36/3/295/

- ↑ http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/media/detail.php?source=hospital_news/2013/20131022a_hn

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 http://law-journals-books.vlex.com/vid/assessing-trauma-substance-sample-homeless-77148905

- ↑ http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2011/08/mental-illness.aspx

- ↑ http://lookoutsociety.ca/solutions/our-facilities/shelters

- ↑ http://sasi.group.shef.ac.uk/publications/reports/Crisis_2012.pdf

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 http://www.owhn.on.ca/pdfs/Women_Homelessness.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9836164

- ↑ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/481800

- ↑ https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/211976.pdf

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jennifer-weisswolf/blood-in-the-streets-menstruation-homelessness_b_9019638.html

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/41345129

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9870331 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "fifteen" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ https://www.huduser.gov/Publications/pdf/2009_homeless_508.pdf

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258122606_Utilization_of_Birth_Control_Services_among_Homeless_Women

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 http://bcpovertyreduction.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/2013_prc-lgbqt-poverty-factsheet.pdf

- ↑ https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/news/2010/06/21/7980/gay-and-transgender-youth-homelessness-by-the-numbers/

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 http://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/InvisibleMen_Summary.pdf

- ↑ http://www.homelesshub.ca/blog/infographic-wednesday-preventing-tragedy-lgbtq-youth-homelessness

- ↑ http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.92.5.773

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 http://www.homelesshub.ca/blog/infographic-wednesday-preventing-tragedy-lgbtq-youth-homelessness

- ↑ http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315

- ↑ http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1058&context=sociologyfacpub

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 ttps://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/report/2016/01/07/128323/discrimination-against-transgender-women-seeking-access-to-homeless-shelters

- ↑ http://bcnpha.ca/media/Conference_2013/Presentations/T3-TRANSITIONING_OUR_SHELTERS_-_Excerpts.pdf