Foot Binding in China

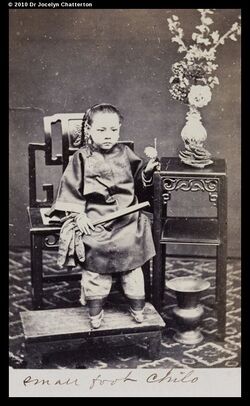

Foot Binding was a Chinese cultural practice that involved tightly bandaging women's feet to restrict normal growth and make the feet look as small as possible. The practice originated in the 10th century during the reign of the Tang dynasty and lasted until the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

The process would begin when the girls would be five years old as their bones were flexible and pliable. The process involved dipping the feet into hot water and clipping the toenails short. Next, the feet would be massaged and oiled until all toes, except the big toe were broken and bound flat against the sole, making a triangular shape. Then the foot was bent double to a degree where the toes and heel met, deforming the arch of the feet. And finally to keep the feet bound in place they were very tightly tied by silk strips.[1]

These bounded feet required utmost care and attention because the binding would often lead to inflammation and ultimately rotting of the flesh. Their feet would be washed time and again to peel off the rotten flesh. Apart from the bone breaking pain and rotting flesh, infection was a common problem and death from septic shock was a common occurrence.[2]

Views and Interpretations

A Status Symbol

The fashion for bound feet began in the upper classes of the Han Chinese society, but it spread to all but the poorest families. Having a daughter with bound feet signified that the family was wealthy enough to forgo having her work in the fields.[3] The class of Gai - comprising of beggars, were discriminated against. The men were forbidden an education and women were not allowed to bind their feet.[4] For the upper class women Foot binding was a mark of their hierarchy and for lower class girls Foot binding was seen as a means to ascend the social ladder.[4] Having bound feet meant having the ideal body type which ultimately allowed women to develop a sense of worthiness and acceptance in the society.[5]

A Beauty Standard and Erotic Appeal

These tiny, deformed feet came to be known as lotus feet making them a symbol of feminine beauty in the Chinese society. By the Ming dynasty it was regarded as the ultimate manifestation of femininity.[6] The most desirable brides possessed a three inch foot known as a "golden lotus”.

It was also respectable to have a four inch feet, the “silver lotus” but five inch or longer were disregarded as “iron feet” and marriage prospects for such women were poor.[7]

Jin Suxin, one of the last few women living with bound feet reminisces about the time when her uncle insulted her by calling her bound feet “big and fat” and embarrassing her in front of a crowd by saying, “Who will be willing to be your matchmaker?” Humiliated, she decided to bind her feet even tighter.[4] Her uncle's cruel comment and mocking triggered her sense of shame. In societal terms, the humiliation and fear of losing face prompted the nine-year-old girl to endure the inhuman pain of reshaping her feet. Young girls were willing to endure a lifelong of pain and disability for acceptance and aesthetics. Small feet were not only considered a sign of sophistication and refinement but also visually stimulating and intensely erotic. The golden lotus, a euphonious term for bound feet, was originally a special apparatus made of gilded gold in the shape of lotus petals on which palace dancers walked and danced.[8] Chinese men desired women with tiny feet. According to Wang Ping bound feet became an object of seduction and lust through physical and linguistic violence. The physical mutilation symbolized a combination of human and beast, and gave the idea of an androgynous body.[4] According to Robert van Gulik, bound feet were also considered the most intimate part of a woman's body. Erotic art of the Qing and Song period openly depict male and female genitalia, but bound feet were never depicted uncovered.[9] While the famous psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud considered Foot binding to be a “Pervasion that corresponds to foot fetishism.”

A Product of Confucian Philosophy

Recent English scholarship on Chinese women viewed the practice as a mere function of Confucian and Neo Confucian thought. Patricia Ebrey points out in her book, Women, Marriage, and the Family in Chinese History (1990) that the rise of Foot binding is linked to a redefinition of masculinity in the Song period (960—1279). The Tang dynasty (618-907) saw women as active and robust, however as Confucianism gained popularity around the 11th century, we began to see a decline in the status of women.[4]

Feminist Theories

An Oppressive Practice

Most Scholars and feminists view Foot binding as a sexist and oppressive practice that stripped women of their rights and freedom through systemic violence. Not only did it symbolize a girl’s willingness to obey but also rendered them powerless. As bound feet reduced womens mobility, they became increasingly dependent on the males in their families, reducing women to nothing but objects of lust and eroticism.

Early Chinese feminists Qui Jin was one of the first to unbind her feet in an act of defiance against the Chinese traditionalism.

She believed that as long as women kept their feet bound, they were giving in to the oppression and continued to be subservient to men by being dependent on them. She advocated for women to emancipate themselves through education and new mental and physical qualities.[10]

Body Politics

New feminist scholarship emerging in China started viewing Foot binding not only in terms of an oppressive and suppressive societal practice that made women vulnerable, but also in terms of 'bodily freedom'. Published in 1997 Fan Hong’s monograph viewed Foot binding as an ominous social practice that deprived women of the abilities to control their bodies. Through a refreshing lens, Fan illustrates how women's empowerment movements in the 1920’s try to reclaim freedom and power for their bodies and strengthen female physicality through intensive exercise.[11][12]

On the other hand, scholars like Wang Ping analyzed the body politics of Foot binding in a different light. The body for Wang was a work of art. This body must be mutated and damaged so it could gain meaningfulness and legitimacy to the other.

However, more recent scholars like Dorothy Ko have asserted different views. Ko believes that feminists have mistakenly imposed 21st century western ideas of freedom and agency on a highly traditionalist culture. According to her, women bound their feet for many reasons that elude our knowledge, and it would be wrong of us to apply our understanding of our bodies to their struggles.[11] Hence she believes that Foot binding could not be situated in any binaries of “black-and-white, male-against-female and good-or-bad way of understanding the world.”[13]

Utilitarian view of Foot Binding

Scholars like Hill Gates and Laurel Bossen refute the claims that Foot binding was an oppressive social practice, unrealistic beauty standard or means to render women powerless. In her book Foot Binding in Sichuan, Hill argued that Foot binding was actually important for work.[14] With their feet bound women were taught and disciplined to spin, weave and do other homework because many village families depended on this as a means of side income.[15]

References

- ↑ Jiahui, Sun (2015). "Three-inch golden lotus: the practice of foot binding". The world of Chinese.

- ↑ Newham, Fraser (2005). "The ties that bind". The Guardian.

- ↑ Szczepanski, Kallie (2019). "The History of Foot Binding in China". ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Ping, Wang (2000). Aching for Beauty: Foot Binding in China. University of Minnesota press. pp. 29–53. ISBN 978-0385721363.

- ↑ Fedorak, Shirley (2007). How does Body-Image affect Self-Esteem, Well-Being and Identity. University of Toronto press. p. 86. ISBN 9781487593216.

- ↑ Mankoff, Debrah (2010). Icons of Beauty: Art, Culture and the Image of Women. Greenwood press. pp. 217–244. ISBN 978-0-313-33821-2.

- ↑ Jiahui, Sun (2015). "Three-inch golden lotus: the practice of foot binding". The world of Chinese.

- ↑ Schiavenza, Matt (2013). "The Peculiar History of Foot Binding in China". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Van Gulik, Robert (1961). Sexual life in ancient China:A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. ISBN 9004039171.

- ↑ "1907: Qiu Jin, Chinese feminist and revolutionary". ExecutedToday. 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Anh Lee, Huy (2014). "Revisting FootBinding: The Evolution of the Body as Method in Modern Chinese History". Inquiries Journal. 6.

- ↑ Hong, Fan (1997). Footbinding, Feminism, and Freedom: The Liberation of Women's Bodies in Modern China. Routledge. pp. 90–96. ISBN 978-0714646336.

- ↑ Ko, Dorothy (2005). Cinderella’s Sisters, A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press.

- ↑ Gates, Hill (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. ISBN 9780415525923.

- ↑ Bossen, Laurel. Bound Feet Young Hands. Stanford University press. ISBN 9780804799553.