Feminism in Korea

Feminism in South Korea has experienced some major changes recently. The exposure of women’s labor being exploited from 1910-1945 under Japanese colonialism to South Korea’s economic boom between 1961 and 1996 stirred a lot of momentum in the women’s movement. The consequences of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 to 2001 led to the entire economic system being restructured, situating women in the background, left to have their rights forgotten. Furthermore, the Korean patriarchy is infamous for blocking women’s sexual and economic autonomy, forcing determined gender ideologies, and historically limiting acceptable social roles for women.[1][2]

History

Prior to the Asian Financial Crisis

Before the creation of the Korean Women’s Associations United (KWAU) in 1987, women’s issues were not considered a primary concern due to other ongoing issues such as the controversy around Korea being a divided nation, as well as South Korea being ruled by a military regime. The Gwangju People’s Uprising in 1980 and the transfer of power to the Chun Doo-Hwan regime constituted the political background against which the women’s movement came into existence.[3] These political events led to the first Women’s Conference in 1985, pursuing women’s labour rights under the slogan “women’s movements along with nation, democracy and people”.[3]

Prior to 1986, no woman in Korea had come forward with sexual assault allegations. The first to do so was a woman named Kwon In-Suk, who eventually became a reason for the creation of the KWAU in 1987, after a large conspiracy around the cover-up of her case, her eventual imprisonment, and the media villainizing her allegations.[4][5] However, because there were no institutions to take full charge of women’s affairs, the government was not able to carry out consistent policies for women.[3] This was one of the fundamental reasons for the creation of the KWAU.

Korean Women's Associations United

The KWAU, which is the organization housing 33 other associations focusing on women's rights in South Korea, used their strength in numbers to advocate for reforms to government legislations that have been historically oppressive to women.[6]

Some major achievements of the KWAU prior to the financial crisis include the enactment of a law against sexual violence and the protection of victims in 1993, as well as a law for the prevention and punishment of domestic violence in 1997. In 1995, KWAU recruited and promoted female candidates in politics, with 14 out of the total 17 being elected that year. The organization also promotes maternity leave, issues surrounding childcare, equal pay for equal work, job creation for women, and the abolition of the family head system, which was finalized in 2005 after a 10 year battle.[7][8]

Post Asian Financial Crisis

In 2013, Aie-Rie Lee and Hyun-Chool Lee argued that “women’s organizations in Korea have served as agencies through which women’s socio-economic and political circumstances can be improved, effectively connecting the everyday lives of women with politics.”[9]

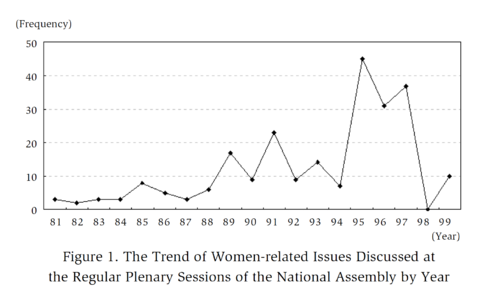

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-2001 wreaked havoc on South Korea. As shown in Figure 1 above, due to the crisis all the data for women-related issues discussed at the National Assembly was lost during 1998.[3] However, the Asian Financial crisis brought enormous changes to Korean feminism, including the introduction of state-feminism - where academics with women’s studies backgrounds were brought into the political realm, and attempts to change male-dominated areas of society were made both politically and non-politically. With the unemployment rate reaching a staggering 8.1% and wages dropping 14%, Korean society (and women in particular) began to realize that relying only on male income would be unsustainable.[10][11] These realizations led to delayed marriage, decreased marriages, decreased fertility rates, increased divorce rates, as well as the creation of consumption and body image as new indicators of desired identity.

All of these changes pushed the Korean women’s movement to criticize and attempt to abolish the patriarchal family system. This system, also known as the family head system, is known to produce and maintain a gender hierarchy in which women are positioned solely as dependents of men. Its abolishment in 2005 is considered the most major success of women’s rights activists in South Korea.[1][10][12][13]

Commercialization of Girl's Bodies

Femininity and women's bodies evolved in South Korea to a point where the new ideal woman is self-fulfilled yet forever girly. Coupled with this is a demand for intense body care, including the almost necessity of plastic surgery to improve one's life and advantages. Perfecting appearances is, above all else, crucial to breaking into the job market - where it is known that attractive people have an advantage over others. Plastic surgery and media impacts are not about vanity in South Korea - it is about ethical responsibility, self-discipline, and moral obligation.[10][14][15] Korean women have also been historically denied sexual freedom unless it is through voyeurism (consuming media) or through narcissism (creating an attractive body).[15] When Hallyu, also known as the Korean Wave, took the world by storm, Korea launched the medical tourism industry with plastic surgery as its largest market in 2007. As Angela McRobbie stated in 2012, "it was through the intersection of popular and political culture that feminism was undone."[16] This is very apparent in Korean culture as these two major industries work hand in hand, not only to bring in massive profits for the Korean government, but to shape and influence society.[17]

Plastic Surgery

Koreans consume plastic surgery at the highest rates per capita globally, with at least 20 out of every 1,000 people getting cosmetic surgery. At least 1 in 3 women between the ages of 19 and 29 state that they have received some type of cosmetic surgery.[10][18][19]

Evidence of cosmetic surgery is a marker of one's social status and wealth. It also shows a willingness to invest in one's appearance in the consideration of others. Parents in Korean society often apologize to their children for passing on faulty genes or lacking the resources to fix these faults through surgery - creating a whole new social class, appropriately titled the "cosmetic underclass".[14] By undergoing cosmetic surgery, these women show their parents their willingness to submit to physical pain in order to erase evidence of their parents' inability to ensure their success. Obtaining cosmetic surgery is indeed an act on par with the Confucian philosophy of filial piety.

Women’s bodies have become the tool for raising self-value, lifestyle, satisfaction and social status. Since universities and employment applications require a photograph to apply, surgery practices have steadily become more popular and accepted in society, as detrimental as that may be.[10] Possibly the most vital reason as to why cosmetic surgery is so present in Korean society is due to pressures induced by peers, family, and the media.[20] Women who do not invest in alterations of the face and body are seen as not only lazy and incapable, but a disgrace to their family and society as a whole.[14][17] These women reportedly feel underprivileged and abandoned by society. Understandably so, Korean feminists see this acceptance of plastic surgery as a system of oppression as well as a backlash to their legacy of wanting equality and the strength to oppose many generations of forced patriarchy.[20]

Impacts of the Media

With a contribution of over $11 billion USD to the Korean economy yearly, creating flawless and perfectly designed faces of the Korean entertainment industry has become crucial to the Korean market. Industry leaders such as SM Entertainment and YG Entertainment carefully and meticulously construct new identities for the future "idols" of Korea. Girl groups specifically are groomed and marketed as being sexually ambiguous: often having an over sexualized appearance but deemed pure and wholesome in all other aspects.[21] A substantial amount of research has been completed recently that sheds a lot of light onto the darker sides of the Korean entertainment industry.[22][23][24][25]

Fans of girl groups include a large portion of men in their 30s and 40s, known in Korean as "uncle-fans". Through this naming of "uncle", the male gaze becomes legitimized and normalized under the guise as caring for their "nieces" - effectively masking the explicit and excessive sexual imagery associated with girl groups. By dissolving the guilt and blame surrounding their pedophilic tendencies, male consumption of the female body again becomes normalized.[21]

In the realm of advertising, Korea suffers greatly from the concept of “sex sells”. While attempting to understand women in the workplace as well as Korea’s sexist advertisements, East Asian studies scholar Olga Fedorenko interned at an advertising agency to find out that roughly half of the employees were female - many in charge of said advertisements. In her research, she found that while half of the employees were female, very few were in managerial positions.[2] While many of the employees there were feminists or exposed to feminist critiques, they still pushed the concept of “sex sells” in order to carry on their professional careers and show their male superiors that they are good enough for the job. Many of these women-led advertisements attempt to subtly undermine patriarchal stereotypes, but ultimately it does little to disrupt the ever prevalent exploitation of the female body.[2]

Also interestingly enough, Fedorenko found in her research that the only complaint female creatives in relation to sex-appeal advertising was the lack of sexualized males in advertising.[2]

Ongoing Struggles

Issues Regarding the Inclusion of Lesbian Activists

Korea has long been a “heterosexual” country - with many Koreans going so far as saying “there are no gays in Korea”.[26] There are many issues with a statement like that - one of which has been the struggle of inclusion of lesbian feminist activists among their heterosexual feminist counterparts. Due to the homophobic nature of women’s movement activists, lesbians are continually erased from Korean feminism, resulting in a significant number of closeted activists.[27] The fight for equality for women in Korea does not include equality for homosexual women - resulting in a rather drastic split between movements and groups.[1]

Women in the Military

A two-year military conscription is mandatory for all Korean men. Inclusion of women in the military has been an ongoing struggle for Korea. Since the beginning of the Korean war in 1949, only men have been obliged to serve in the military, while a small number of women have been given very limited privileges to handle auxiliary functions. By law, women are prohibited from participating in combat, which leads to their replacement by men during times of war.[28] This is rather controversial and unfortunately the Korean military has continued their sexist practices. One astonishing example of this is the Naval Academy's guidebook on "Female Students' Relations with the Opposite Gender," where women were strongly advised to apply only basic and neutral makeup, strongly scented perfumes were banned and undergarments should “not sully the student’s dignity". The pamphlet suggests that women who are sexually assaulted have only themselves to blame.[29]

As Sojeong Park states in her 2017 article, "many men accuse women for free-riding on the nation’s security that they provide....[and they] say 'women don’t pay us for our efforts to protect the country.'"[30] A lot of resentment on both sides stems from the issues surrounding the Korean military, unfortunately not much is being done to solve these issues.

Women in the Workplace

The economic crisis inflated discriminatory employer practices towards women. Due to extreme wage gaps between males and females across all areas of employment, women were consistently pressured into irregular employment (part-time work with no job security, no benefits and no unions).[31] Irregular employment is now dominated by women, with 70% of women employed as part-time workers and other forms of irregular work. Unions in Korea overwhelmingly represent male workers and ignore the requests of women - refusing to adapt their policies to fit the lives and concerns of women in the workplace. Any efforts taken by women to publicize these discriminatory practices have been largely ignored by not only unions, but by the government and media as well.[31]

Women in Korea also have a very hard time obtaining permanent careers, due to the societal pressures to marry and have children. Many women in permanent positions are either single or “abandon” their children - by leaving them with a nanny or the grandparents. The double standard here is proven by Fedorenko’s interactions with a woman in the advertising agency who noted that “if a man had a picture of his child in his cubicle, he was praised as “family-oriented,” but if a woman displayed a picture of her child, people criticized her saying that “she thinks only about home,” meaning she was unprofessional”.[2]

Sexual Violence

In 2016, a survey by the Ministry of Gender, Equality and Family found that 8 in 10 respondents had experienced sexual harassment at work. In a similar study done in 2017 by the Korean Institute of Criminology, 8 out of every 10 men admitted to abusing their girlfriends.[32] Women who experience sexual harassment at work are forced to choose between keeping their job (by dropping their assault claims - and taking a pay cut) or losing their job and having to deal with the aftermath.

There is also another outbreak of sexual harassment in Korea - that of revenge porn and digital voyeurism. Due to this, the Korean government banned silent cell phone camera shutters (yes, every cell phone in Korea is equipped with the little click every time a photo is taken) and has instructed companies to check public washrooms for hidden cameras on a monthly basis.[32] The main website these videos were uploaded to was taken down 15 years after its creation - and even though all the information on the website was publicly accessible, authorities refused to take action as it was too legally “complicated”. The users of the website (numbered at over one million) not only utilised the site to post images and videos from hidden cameras, but also to plan, carry out, and document rapes of Korean women, as well as to buy and sell date-rape drugs.[33]

In 2005, an investigation into Gwangju Inhwa school found that six teachers, including the school principal, sexually molested or raped at least nine of their deaf-mute students between 2000 and 2003. The students were between the ages of 7 and 22. Only four of the criminals received prison terms - the other two were set free immediately. Of the four jailed, two were released less than a year later. Four of the six teachers went back to continue working at the school.[34] Since then, many laws have been changes - albeit slowly. At the time, there was a law in place that barred the prosecution of a child sex offender unless the victim made the complaint himself or herself. This law was changed only in 2010. Additionally, the "Dogani Bill" was passed in October 2011, which eliminates the statute of limitations for sex crimes against children under 13 and disabled women. This bill also, thankfully, increases the maximum penalty to life in prison.[34]

In the Miryang gang rape case of 2004 and 2005, 44 high school students raped two sisters in middle school repeatedly for over one year. Each time, the groups of rapists would range from 4 to 10 in number. The case ended with some of the students being sent to juvenile court and the rest being released. One police officer on the case remarked, young wenches like you, barely off your mother’s milk, going around and seducing boys, have brought disgrace to my hometown, Miryang!”[1] The police also, after lining up 41 accused offenders, asked the victim to point out each of her offenders - while asking “Did he insert [it] or not?” after making the victim confront each offender directly. She eventually had to be hospitalized for psychiatric treatment due to the trauma. The rapists’ girlfriends defended the men, resorting to calling the victims awful slurs online. Dually, the parents of the rapists took on the role of victim - their family was suffering, because “who can resist temptation when girls are trying to seduce our boys?”[1]

On the evening of May 17th, 2016, a women was murdered by a man she never met before in a public bathroom near Gangnam subway station. According to security footage, the murderer let six men pass by unharmed before stabbing the innocent woman. His reasoning was simply that she was a woman, and that he was tired of women ignoring him. Evidently a hate crime, the media covered it up by stating it was a "random" murder and blamed it on the murderer's psychological state. Women took to the streets over the next few weeks and plastered the historically busy subway station with sticky notes, candles, and flowers. This image still persists today: many of the sticky notes are still attached to the subway station. This issue sparked a massive new wave of feminism in South Korea. The murderer was charged with 30 years in prison.[35][36][37]

The Evolution of the Women's Movement

Korea is known for having a quickly developing economy and very fast history - the women's movement is no different. Many rallies, protests, and advancements in the movement are organized and developed online. In fact, the internet has become the top organizing space for Korean feminism.[38][39] Hashtag movements dominate the Korean webspace, bringing massive awareness to the struggles women face.[39]

The women's movement has become increasingly more aware of intersectionality, with a large focus on class and age differences along with gender. As the older generation of men hold all the power in Korea, a lot of feminist frustration stems from the impact of these men on society - their sons and daughters in particular.[38]

The Impact of Megalia and Womad

The most well-known feminist groups in Korea are Megalia and Womad. Although their presence in society has brought forth some great changes, these two groups are extremely radical and are generally seen in a very bad light. Their existence, along with the far-right men’s rights group Ilbe, has pushed the gender war into the foreground of social issues in Korea.

The first major “win” for Megalia was the removal of a controversial Maxim magazine cover. The cover depicted a Man standing at the trunk of a car, with a woman’s bound legs dangling out of the trunk. The controversial cover was eventually taken down and Maxim US issued an official apology.[40] Megalia is also partially responsible for the eventual shut-down of SoraNet, the revenge porn website.[41]

However, it’s safe to say that Megalia and its sister site Womad have done more harm than good. Megalian activists use the concept of “mirroring” on message boards, where they rewrite misogynistic comments by replacing the words “women” and “men”. While this may have been effective in the beginning, the community has since taken it too far. Examples of their radicalism include the rape of a young boy in Australia,[42] a school teacher stating she wanted to have sex with an underage student,[43] strangling and murdering a kitten because it was male (and posting photos of it),[44] celebrating intentional miscarriages of baby boys,[44] and exposing nude images of men without their consent.[45] Womad, the sister site of Megalia, is considered to be a Korean-style TERF group, showing extreme hatred towards those of sexual minorities. Both groups also consistently out gay men.[46]

Unfortunately, because these two groups have made the biggest impact on Korean society under the guise of feminism, many Koreans immediately think of these groups when the term “feminist” is uttered. The women’s movement in Korea has thus far accomplished many great things, but it still has a long way to go.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Cho, Joo-Hyun (2005). "Intersectionality Revealed: Sexual Politics in Post-IMF Korea". Korea Journal Autumn 2005: 86–116.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Fedorenko, Olga (2015). "Politics of Sex Appeal in Advertising". Feminist Media Studies. 15:3: 474–491.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Kim, Kyounghee (Summer 2002). "A Frame Analysis of Women's Policies of Korean Government and Women's Movements in the 1980s and 1990s". Korea Journal: 5–36.

- ↑ West, James M.; Baker, Edward J. (1991). "1987 Constitutional Reforms". Human Rights in Korea: Historical and Policy Perspectives: 247–248.

- ↑ "Assessing Reform in South Korea: A Supplement to the Asia Watch Report on Legal Process and Human Rights". Asia Watch: 33. 1988.

- ↑ Nam, Jeong-Lim (2000). "Gender Politics in the Korean Transition to Democracy". Korean Studies. 24: 94–112.

- ↑ "Korea Women's Associations United".

- ↑ Hur, Song-Woo (2011). "Mapping South Korean Women's Movements During and After Democratization: Shifting Identities". In Broadbent, Jeffrey; Brockman, Vicky (eds.). East Asian Social Movements: Power, Protest, and Change in a Dynamic Region. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 181–203. ISBN 978-0-387-09626-1.

- ↑ Lee, Aie-Rie; Lee, Hyun-Chool (2013). "The Women's Movement in South Korea Revisited". Asian Affairs: An American Review. 40: 43–66.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Cho, Joo-hyun (Autumn 2009). "Neoliberal Governmentality at Work: Post-IMF Korean Society and the Construction of Neoliberal Women". Korea Journal: 15–43.

- ↑ Choi, Yongsok (January 2002). "Social Impact of the Korean Economic Crisis". EADN Regional Project on the Social Impact of the Asian Financial Crisis: 1–19.

- ↑ Yang, Hyeon-a (2000). "Hojujedo-ui jendeo jeongchi: jendeo saengsan-eul jungsim-euro" [Gender Politics in the Korean Family-Head System: ItsGender Production]. Hanguk yeoseonghak (Korean Journal of Women’s Studies). 16:1: 65–93.

- ↑ "Welcoming Statement on the Occasion of the Abolishment of the Hoju Registry System". KWAU. Korean Women's Association United. 2005.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Elfving-Hwang, Joanna (June 2013). "Cosmetic Surgery and Embodying the Moral Self in South Korean Popular Makeover Culture". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 11:24:2: 1–16.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Fedorenko, Olga (2015). "Politics of Sex Appeal in Advertising". Feminist Media Studies. 15:3: 474–491.

- ↑ McRobbie, Angela. "Post Feminism + Beyond". 2012. Youtube.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lee, Sharon Heijin (2016). "Beauty Between Empires: Global Feminism, Plastic Surgery, and the Trouble with Self-Esteem". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 37:1: 1–31.

- ↑ "In Seoul, A Plastic Surgery Capital, Residents Frown On Ads For Cosmetic Procedure". National Public Radio, inc. 2018.

- ↑ "Here are the vainest countries in the world". Business Insider. 2015.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Puzar, Aljosa (June 2011). "Asian Dolls and the Westernized Gaze: Notes on the Female Dollification in South Korea". Asian Women. 27:2: 81–111.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kim, Yeran (2011). "Idol Republic: the Global Emergence of Girl Industries and the Commercialization of Girl Bodies". Journal of Gender Studies. 20:4: 333–345.

- ↑ Saeji, Cedarbough T. (July 2018). "Regulating the Idol: The Life and Death of a South Korean Popular Music Star". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 16:13-3.

- ↑ Epstein, Stephen; Joo, Rachael Miyung (August 2012). "Multiple Exposures: Korean Bodies and the Transnational Imagination". Asia-Pacific Journal. 10:33: 1–17.

- ↑ Turnbull, James (2017). "Just Beautiful People Holding a Bottle: The Driving Forces behind South Korea's Love of Celebrity Endorsement". Celebrity Studies. 8:1: 128–135.

- ↑ Maliangkay, Roald (2015). "Uniformity and Nonconformity: The Packaging of Korean Girl Groups". In Lee, Sangjoon; Nornes, Abe Markus (eds.). Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 90–107.

- ↑ Lim, Jason (2014). "There are no gays in Korea". The Korea Times.

- ↑ Jeong, Chun-hi (2004). "Yeoseongjuui jinyeong-eun dongseongae isyu-e daehae baewoya" [The Feminist Movement Has More to Learn about Lesbian Issues]. Ilda (Waves of Those Women Are Rising).

- ↑ Hong, Doo-Seung (2002). "Women in the South Korean Military". Current Sociology. 50:5: 729–743.

- ↑ Kim, Young-Ha (2014). "South Korea's Sexist Military". The New York Times.

- ↑ Park, S. (2017). "Misogyny in Hell-Joseon: An Intersectional Approach to the Misogyny of South Korean Society". The Asian Conference on Cultural Studies 2017 - Official Conference Proceedings. 1-11.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Chun, Jennifer Jihye (2008). "The contested politics of gender and irregular employment: the revitalization of the South Korean Democratic Labour Movement". Labour and the Challenges of Globalisation: What Prospects for Transnational Solidarity: 23–44.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Paulo, Derrick A. (February 2018). "In South Korea, a society faces up to an epidemic of sexual harassment". Channel News Asia.

- ↑ Kurmelovs, Royce (May 2016). "Let's Talk About the Toxic Way South Korea Is Handling its Rape Problem". Vice.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Choe, Sang-hun (October 2011). "Film Underscores Koreans' Growing Anger Over Sex Crimes". The New York Times.

- ↑ Byun, Hee-jin (2017). "Top court upholds 30-year prison term for Gangnam murder". The Korea Herald.

- ↑ Park, Seohoi (2017). "Murder at Gangnam Station: A Year Later". Korea Exposé.

- ↑ Ko, Hansol (May 2016). "Mourners crowd Gangnam Station exit 10 to mourn murder victim". Hankyoreh.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Yang, Sung-Hee; Noh, Shin-Young (June 14, 2018). "Korean feminism: 'Fourth-wave in form, but second in content'". Korea JoongAng Daily.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Kim, Jinsook (2018). "After the disclosures: a year of sexual_violence_in_the_film_industry in South Korea". Feminist Media Studies. 18:3: 505–508.

- ↑ Steger, Isabella (2016). "An epic battle between feminism and deep-seated misogyny is under way in South Korea". Quartz.

- ↑ Singh, Emily (2016). "Megalia: South Korean Feminism Marshals the Power of the Internet". Korea Exposé.

- ↑ Kim, Heewon (2017). "Korean Radical Feminist Allegedly Committed Child Sexual Assault in Australia". Korea Daily.

- ↑ Ku, Ja-yun (2015). "메갈리안 유치원 교사 "어린이와 하고 싶다" 논란" [The Megalian kindergarten teacher's 'I want to do it with a child' controversy]. The Financial News.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Kang, Hyun-Kyung (2018). "Radical feminists in sick competition of cruelty". The Korea Times.

- ↑ Lee, Clair (2018). "'Feminist' group probed for link with online sexual harassment in South Korea". The Korea Herald.

- ↑ "한국형 TERF인 '워마디즘' 비평" [Korean-style TERF "Womadism" criticis]. Huffington Post Korea. 2017.