Dostoevsky's Biblical influences

Fyodor Dostoevsky was a devout Orthodox Christian whose faith was central to his works. When Dostoevsky was sentenced for four years of hard labour in Siberia, all he had to read was a gifted copy of the Russian translation of the New Testament (Kjetsaa). In prison, Dostoevsky would occasionally read passages and stories from the Bible aloud to himself or to others. After being released from prison, Dostoevsky kept that same copy of the New Testament on his writing desk. Dostoevsky would continue to read the New Testament in times of stress, anguish, or at random.

Crime and Punishment

In Crime and Punishment, the act of a crime follows a psychological burden or guilt that consumes the guilty. For example, Rodion Raskolnikov suffers throughout the novel for his crime of murdering the pawnbroker Alena Ivanovna and her half-sister, Lizaveta. However, the novel also propagates a third arc: redemption, or reconciliation in accordance with Christianity. Reconciliation, according to the Catholic Church, occurs when one restores their ties, or relationship, with God, usually by atoning for one’s sins and aiming for a holier lifestyle (396-397). Reconciliation is presented in Crime and Punishment as the optimum step one can take when faced with the psychological consequences of one’s grave sins. The influence of Christianity is highlighted with this theme in Part Four: Chapter Four when Sonya reads to Raskolnikov from the Gospel of John. In this scene, Sonya symbolically raises Raskolnikov from his spiritual death as he comes to accept the word of Christ. Christian theology follows a concept of spiritual death, where the human soul ‘dies’ as a result of disconnection from God (Catholic Church, 508). Raskolnikov, a character similar to Dostoevsky prior to his conversion who has been both irreligious and experimenting with atheistic / nihilistic worldviews, would be considered to be spiritual dead. Valentina Izmirlieva describes Raskolnikov’s conversion when during the reading from the Gospel of John, Raskolnikov finally comes to turn to her to ‘face’ the Word of Christ (284). In the same chapter earlier, Izmirlieva explains further eschatological symbolism through the decision Sonya must make in whether to help Raskolnikov or not. Izmirlieva describes this exchange as a scandal of ‘radical hospitality’ that follows what Christ asks of his followers in Matthew 25, requesting that his followers actively help those in need, especially strangers, lest they be punished for not doing so in the Final Judgement (278). By coming to Sonya, Raskolnikov presents himself as a stranger in need and Sonya is tested for her faith with the decision of whether to help him or not, which she does.

In contrast to Raskolnikov’s conversion and reconciliation are two alternatives that Dostoyevsky describes in Crime and Punishment through the characters of Semyon Marmeladov and Arkady Svidrigailov. Marmeladov met his fate in Part Two, Chapter Seven after he was run over by a carriage on the streets and dies due to his wounds. His ‘crimes’ as described in the novel by Marmeladov’s conversation to Raskolnikov in Part 1, Chapter 2, were neglecting and failing to provide for his children, resulting in him suffering and drowning his sorrow through alcohol. Marmeladov’s redemption is met due to his status as a dying individual, which permits him to and has him ask for his last rites from the nearby priest, resulting in his forgiveness and redemption according to Christian tradition (Catholic Church, 424). Svidrigailov, who Daniel Schümann describes as a ‘contrast’ to Raskolnikov is presented by Dostoevsky with his ‘crime’ as the attempted rape and lust of Raskolnikov’s sister (14). Svidrigailov suffers as a result of lust, seen with his nightmare of the little girl in Part 6, Chapter 6, which results in his suicide later in the same chapter. According to Christian doctrine, Svidrigailov does not redeem himself as the sin of suicide is unredeemable, and thus, Svidrigailov meets a tragic end unlike Marmeladov or Raskolnikov (Catholic Church, 609).

The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov focuses heavily on religious themes and questions, with characters alluding to the Bible many times (Winter). One of the strongest examples of this focus on religion is found in book 5: chapter 5: “The Grand Inquisitor”. Ivan recites his poem, “The Grand Inquisitor,” to Alyosha. “The Grand Inquisitor” deals with a hypothetical scenario in which Jesus Christ is reborn in Seville, Spain. As Christ moves through the city, people recognize him immediately and are in reverence of him, but this calls on the attention of the Grand Inquisitor, who quickly arrests Christ. After confirming Christ’s identity for himself, the Inquisitor scorns Christ for giving humanity free will. The Inquisitor states that free will has been a bane on people’s existence, and that, to fix Christ’s mistake, now the Church must rid people of their freedom so to make them happy. The Grand Inquisitor ridicules Christ for his actions in his past life that he made to save humanity:

Didst Thou forget that man prefers peace, and even death, to

freedom of choice in the knowledge of good and evil? Nothing is more seductive for man

than his freedom of conscience, but nothing is a greater cause of suffering. And behold, in-

stead of giving a firm foundation for setting the conscience of man at rest for ever, Thou

didst choose all that is exceptional, vague and enigmatic; Thou didst choose what was utterly

beyond the strength of men, acting as though Thou didst not love them at all (Dostoevsky, 320)

The Grand Inquisitor goes on to tell Christ how the Church will establish a life for the people that is better than the one that Christ left for them. By taking away their free will, and proving them a lifestyle where they do not have to worry about sustaining their lives, the Church will make life for their devotees sinless and enjoyable, rather than burdened with the existential cost of free will. Ivan ends his poem with the Inquisitor sentencing Christ to death the next day. Christ responds by kissing the Inquisitor on his lips. The Inquisitor then lets Christ go, and begs him never to return (Dostoevsky, 327 – 330)

Ivan struggles with believing in a God who allows his devotees to suffer. There is fault to be found not just in the existence of God, a supposedly benevolent and omnipresent being who allows suffering, but in the existence of the Church (Baum). As Ivan sees it, organized religion would either further the suffering inflicted by believing in God and the Bible, or be so defendant in their dogma that they would strip their congregations of free will, having them abide by their words, so that they needn't worry about life's trivial matters. After listening to Ivan's poem, Alyosha gets up and kisses Ivan on the lips, as Christ did to the Grand Inquisitor.

Ivan's "The Grand Inquisitor" Baum states, is rooted in the moral, existential, and religious dilemma of free will : "spiritual freedom, Dostoevsky tells us, is an immense burden, humanity’s greatest, but any attempt on our part to alleviate that burden, even one motivated by sympathy for the suffering, is not only wrong, but is in defiance of God."

Bibliography

Baum, Spencer. "The Grand Inquisitor In Brothers Karamazov". Medium, 2017, https://medium.com/@spencerbaum/the-grand-inquisitor-in-brothers-karamazov-1ca1dd3372e4.

Catholic Church. Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2nd ed. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012. Print.

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Constance Garnett. Lowell Press.

Fyodor, Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment. Translated by Oliver Ready, Penguin, 2014.

Grabar, Igor. “Sonya in the room of dying Marmeladov.” Wikipedia Commons, 1894. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8c/Grabar_Crime_and_Punishment_Sonya_visiting_Marmeladov_1894.jpg

Kjetsaa, Geir. Dostoevsky Studies :: Dostoevsky And His New Testament. 1983.

Izmirlieva, Valentina. The Routledge Companion to Literature and Religion. Edited by Mark Knight, Routledge, 2016, pp. 277-286.

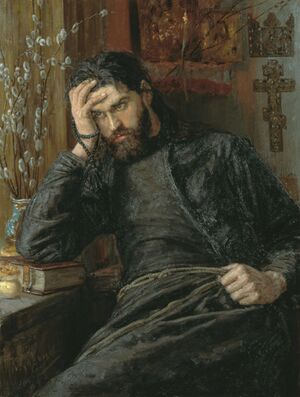

Savitsky, Konstantin. The Monk-Inok. Penza Savitsky Art Gallery, Penza, 1897.

Schümann, Daniel. “Raskolnikov’s Aural Conversion: From Hearing to Listening.” Ulbandus Review, vol. 16, 2014, pp. 6-23.

Winter, Lindy. "Biblical Allusions In The Brothers Karamazov". Accessed 26 Mar 2022.