Documentation:Open Case Studies/SPPGA/The Canadian Government's Response to the 2015 Syrian Refugee Crisis

Introduction

The war in Syria broke out in March 2011, while many countries in the Middle East and North Africa experienced mass demonstrations and uprisings that became known as the Arab Spring. The protests in Syria were triggered by the arrest and torture of a group of students who put up anti-government graffiti. One of the students, a 13-year-old boy, was killed after having been tortured.

Soon, more and more people took to the streets, demanding greater freedom and democracy. By July 2011, hundreds of thousands of people were taking part in the demonstrations, requesting that President Bashar Al-Assad step down from power. Hundreds of demonstrators were killed and many more were imprisoned.

That same month, defectors of the army formed the Free Syrian Army, pledging to overthrow the government. Seven years later, the war in Syria rages on. The conflict in Syria and other parts of the Middle East and Northern Africa was exacerbated by economic downturns, and resulted in record numbers of refugees and economic migrants (known as ‘mixed migratory flows’) trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea to get to Europe.

Displacement from Syria and Mediterranean Crossings

Syrians began to flee from their homes in May 2011. Some people fled to other areas within the country, becoming internally displaced people (IDPs), while others crossed international borders (becoming refugees). The first refugee camps were opened in Turkey, offering what the Turkish government then described as a ‘temporary residence’. Za’atari camp, which would become the home of some 120,000 refugees in just one year, opened in Jordan in July 2012.

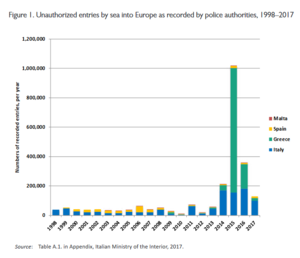

By October 2014, the number of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa risking their lives to reach Europe via the Mediterranean began to increase dramatically.

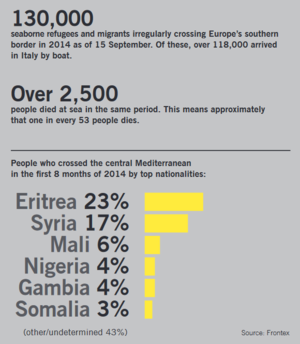

According to a report from Amnesty International, as of September 15, 2014, 130,000 migrants and refugees had crossed the Mediterranean that year. Of these, at least 2,500 died attempting the journey, setting a new record. The crossings are dangerous for many reasons, including the use of flimsy and unseaworthy boats, inexperienced captains, overcrowding, and lack of life jacktets or other safety equipment.

Pictures of the dead bodies of migrants and refugees along the beaches of Italy and Greece were regularly shown by the media. As thousands of people arrived at the southern coast of Europe, the European Union struggled to come up with a coherent policy response. Western countries such as Canada also began to take note of the crisis.

By July 2015, the number of Syrian refugees reached the four million mark, with another eight million people displaced within Syria. On August 17, 2015, the United Nations Security Council expressed “grave alarm over the continuing crisis” in Syria and pushed for a political solution.

Indicators of a worsening situation were shared throughout the fall of 2015. During the commemoration of World Refugee Day on June 20, 2015, the United Nations High Comissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) noted that almost 60 million people around the globe had been forcibly displaced in the previous year- more than at any other time in their records. According to Global Trends 2015 (the UNHCR’s annual report on forced displacement), of the 19.5 million refugees in 2014, the top country of origin was Syria, with 3.88 million of its citizens forced to flee to another country.

Former High Commissioner for Refugees, António Guterres, stated: “These people rely on us for their survival and hope. They wil remember what we do. Yet, even as this tragedy unfolds some of the countries more able to help are shutting their gates to people seeking asylum. Borders are closing, pushbacks are increasing and hostility is rising.”

![]() Video of António Guterres' Statement, from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency.

Video of António Guterres' Statement, from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency.

A Picture Raises the Alarm

On September 2, 2015, four years after the conflict in Syria began, the body of a young refugee boy named Alan Kurdi was found on a beach in Bodrum, Turkey. He had died on a flimsy boat while trying to make his way to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. A photograph of the boy was taken by a journalist and the image quickly became viral in traditional media and social media. The boy’s dead body became an emblem of the Syrian refugee crisis and a call to action for many governments.

The Refugee Crisis and the Canadian Federal Elections

The picture of Kurdi surfaced at the same time as Canada’s federal election entered its last month. Approval ratings for the current Prime Minister, Stephen Harper (Conservative), were at one of the lowest points of his leadership at, 32 percent. This indicated that Canadians were ready for a change in leadership. Given many people’s visceral response to Kurdi’s death, Canada’s answer to the refugee crisis became a key issue in each party’s platforms.

Angus Reid public opinion polls carried out in Canada after the image was published indicated that Canadians generally supported increased action to deal with the crisis. Seventy percent of Canadians surveyed felt that the Syrian refugee crisis was a global problem in which the Canadian government had a role to play, and only 35 percent approved of the current government’s response to the crisis. Under Harper’s leadership, Canada had committed to resettling 1,300 Syrian refugees by December 2014, but only 457 Syrian refugees had been accepted by the end of the year. Harper’s stance on the issue was focused largely on security matters. During a Facebook chat that took place on the week of September 9, 2015, the Prime Minister said:

“We cannot open the floodgates and airlift tens of thousands of refugees out of a terrorist war zone without proper process. That is too great a risk for Canada. ”

In addition, the Convservatives had lapsed $125 million in development assistance in order to report a surplus during the election year.

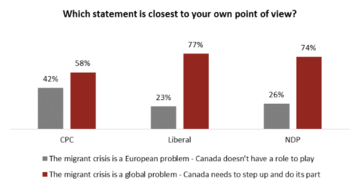

Interestingly, the same polls indicated that opinions diverged strongly between Conservative, and Liberal and New Democrat voters. Over 70 percent of Liberal and New Democratic Party (NDP) voters supported stronger action by Canada, while only 58 percent of Conservative voters felt the same way.

The two main parties seeking to take over leadership, the Liberals and the NDP, correctly perceived the importance of increased solidarity for refugees among their electorates. Each promised to increase the number of Syrian refugees welcomed to Canada in a shorter timeframe. The Liberals promised to bring in 25,000 people by the end of 2015, while the NDP vowed to bring in 10,000 people by the end of the same year. Instead of focusing on refugee resettlement, Harper proposed ameliorating the situation via a combination of military action and admittance of refugees (video below). The incumbent party promised to resettle 10,000 refugees, but only by September 2016.

Video of Stephen Harper sharing his thoughts on the refugee crisis, from CBC News.

The Refugee Crisis and Justin Trudeau

Although horrific, the events of October 2015 presented the perfect opportunity for candidates to push their agendas. In particular, Justin Trudeau, leader of the Liberal Party, promised to bring the largest number of refugees in the shortest amount of time. A cunning politician, he merged a problem, policy and politics. The context also afforded him the opportunity to promote the Liberals’ pro-asylum values, effectively tying his party to Canadian ideals of solidarity, generosity and humanitarianism.

The results of the 2015 elections gave the Liberals a clear majority with 184 seats, as well as 39.5 percent of the popular vote. The Conservatives became the official opposition:

| Liberal | Conservatives | NDP | BQ | Green |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 184 seats | 99 seats | 44 seats | 10 seats | 1 seat |

| 39.35%

of votes |

31.9%

of votes |

19.7%

of votes |

4.7%

of votes |

3.5%

of votes |

Refugee Crisis and the Media

Although the issue of granting asylum to Syrian refugees had been simmering in the news since around 2013, the image of Kurdi’s body brought the issue to the forefront of the medias’ attention and policymakers’ agendas. Policymakers in Ottawa were particularly pressured to prioritize the issue when it was found that the boy’s aunt, Tima Kurdi, was trying to get refugee status for both of her brothers (one of whom was Kurdi’s father). However, after spending months preparing one of the applications that was returned due to being incomplete, she had felt discouraged to seek refugee status for her other brother.

"Obviously, this is devastating for the family. We need to address the situation. We need to look at how we can bring people into our country," said NDP MP Fin Donnelly.

As is the case with many contentious issues, the media played a significant role in bringing the refugee issue to the attention of policymakers. It did this by increasing awareness about refugees and indirectly pressuring politicians to act.

Factiva is an online tool that aggregates 36,000 Sources (media articles, journals, radio transcripts, etc.) to provide researchers and other interested parties with relevant quantitative data. A search for the key words “Syrian Refugees” and “Canada” brought 8,636 results for the period of January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2017. The graph below shows a significant increase in the number of media mentions from 2014 (311 mentions) to 2015 (3,826 mentions), an indication of increased media attention and a proxy for the issue’s agenda status among policymakers.

Factiva does not provide data breakdowns by month, but one would estimate a substantial increase from August to November 2015. This time range includes Kurdi’s death, the federal elections and the terrorist attacks that took place in Paris. This may have contributed to media mentions because it was alleged that one of the attackers held a Syrian passport and had entered Europe via Greece, a popular route among refugees.

Social media also played an important role in getting the issue on political agendas. A comprehensive study by the Visual Social Media Lab, a research firm seeking to better understand the effects of social media and society, indicates that millions of tweets were shared after the initial photograph of Kurdi was published. As the image spread wider and wider, the terminology used changed from ‘migrant’ to ‘refugee’, indicating greater awareness of the situation and increased expectations for accountability from political leaders. A tweet by Liz Sly, the Washington Post Bureau Chief in Beirut, went viral after it was retweeted 7,421 times.

Making a Decision

One of Trudeau’s election promises was the resettlement of 25,000 Syrian refugees. His party won the elections and, as a result of working within a parliamentary system, was able to fully enact his promise with little opposition shortly after coming into power.

Trudeau unveiled his 31-member Cabinet on November 4, 2015. Every member was picked by Trudeau and thus loyal to the Liberal party. They were sure to support any policy or law change that the Government put forward. When Trudeau announced that the resettlement plan would be presented to the Cabinet on November 12, 2015, he was confident that he would have full support from its member who held a clear majority in the House of Commons.

Trudeau was able to swiftly put his refugee plan into action because, as Prime Minister, he and his party had predominant control over the government agenda. Though it is politically sound (and advantageous) to listen to the concerns of the opposition and interest groups, the Prime Minister and Cabinet are free to do as they wish. For example, several settlement groups and former government officials urged Trudeau to slow down the resettlement process, citing logistical concerns. However, keen to keep his election commitment, Trudeau and his party largely kept to their promise.

![]() Video of Former Ontario Deputy Minister of Immigration, Naomi Alboim, discusses liberal refugee plan, from CBC News.

Video of Former Ontario Deputy Minister of Immigration, Naomi Alboim, discusses liberal refugee plan, from CBC News.

Carrying Out the Policy

The Liberals’ policy was implemented in a top-down manner. Several variables enabled its relative success:

- 1. The official name of Trudeau’s policy was #WelcomeRefugees. Although there is no ambiguity in the quantities of refugees and dates involved in the policy, some clarity is lacking in the types of refugees. Note the difference between the term ‘Syrians’ and ‘Government-assisted refugees’ (GARs). The term Syrians could include privately-sponsored refugees[1], Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugee[2], or GARs. This ambiguity ensured some flexibility for the government in terms of how many refugees it would independently have to bring to the country versus how many would be brought by private sponsors.

- 2. At the federal level, the assumptions underlying the Liberals’ refugee plan was plain to see: If Canada resettles more refugees, then the number of refugees in distress will decrease. The resettlement of refugees is the instrument and decreasing the number of distressed refugees is the desired effect. Unfortunately, the Liberals’ assumption was not as accurate at the provincial or municipal level. There was little clarity in what instruments the provincial and municipal governments, as well as civil society organizations, were meant to use to contribute towards distress reduction.

According to the Liberals’ original plan, a total of 25,000 refugees would be brought to Canada by the end of 2015. When it became clear that the ‘how’ in Trudeau’s plan was, for all intents and purposes, inexistent, the plan had to be revised. On November 17, 2015, the government announced that only 10,000 refugees would arrive in Canada by December 31, 2015, and another 25,000 would arrive by March 2016. This delay was due, in large part, to the unrealistic plan of relocating 25,000 people to another country in the space of seven weeks.“We support this goal. But today’s announcement was short on details and we believe Canadians were looking for a concrete plan for getting vulnerable refugees out of harm’s way, not hearing about new cabinet subcommittees,” NDP MP Jenny Kwan said.

![]() Video of Health Minister Jane Philpott, Chair of the Cabinet Subcommittee on Refugees, explains the refugee plan's resettlement delay. “We set a very ambitious target for ourselves, and we have worked very hard to determine how we can best do this”, she said. From CBC's Power and Politics.

Video of Health Minister Jane Philpott, Chair of the Cabinet Subcommittee on Refugees, explains the refugee plan's resettlement delay. “We set a very ambitious target for ourselves, and we have worked very hard to determine how we can best do this”, she said. From CBC's Power and Politics.

- 3. The policy had a sound legal basis and included additional funding, which would serve as an incentive for action. The Liberals’ refugee plan was based on Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which was assented to in 2001. In addition, Canada is party to the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Although the number of refugees admitted to Canada is usually decided by the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, this time the number was decided by the Prime Minister.

- Approximately $950,000,000 was allocated to the initiative. Approximately $600 million was allotted to the provinces and territories outside of Quebec for settlement services, while an additional $6.8 million was provided to settlement agencies and other service providers.

- 4. At the federal level, Trudeau appointed the department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, under the leadership of the then Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, John McCallum, to lead the policy efforts in the horizontal initiative[3]. Other federal organizations involved included Global Affairs Canada and Canada Border Services Agency. Non-federal and non-governmental partners included the UNHCR, provincial and territorial governments, and various resettlement service provider organizations who would support in areas such as language training, help finding work and support with daily life. Trudeau also formed a cabinet ad-hoc committee to facilitate the coordination among agencies. This committee was chaired by the Minister of Health and included the Ministers of Imigration, Refugees and Citizenship, International Development and National Defense.

- At the provincial level, initiatives taken by several provinces serve as indicators of their commitment. Some of the actions taken include:

- Schools in Alberta being asked to find additional spaces for Syrian students

- Health authorities in British Columbia hiring more Arabic interpreters

- Medical officers in Ontario preparing trauma counsellors

- Quebec declaring it would support the resettlement of 7,300 Syrians over two years The steps taken by provincial officials indicate their commitment to the policy outcome. They added and expanded services that would facilitate the local integration of Syrian refugees.

- 5. Many social organizations around the world lauded Canada’s new policy. “This is a huge gesture of solidarity with the Syrian people,” declared then UN High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres.

- In Canada, Liberal leaders supported the policy while other parties showed disapproval, citing the hasty design of the policy and the lack of information about the costs involved. Some were concerned about the policy’s prioritization of vulnerable people and complete families and the exclusion of unaccompanied heterosexual men. Tom Mulcair, leader of the NDP, derided the policy’s exclusion of men, “Excluding them in advance is not the Canadian way”, he said.

![]() Video of Tom Mulcair, leader of the NDP, derided the policy’s exclusion of men, “Excluding them in advance is not the Canadian way”, he said. From CBC News.

Video of Tom Mulcair, leader of the NDP, derided the policy’s exclusion of men, “Excluding them in advance is not the Canadian way”, he said. From CBC News.

- Disapproval grew particularly strong after the Paris attacks, when anti-muslim sentiment increased. Some politicians, such as the Conservative Premier of Saskatchewan, Brad Wall, stated that Trudeau’s refugee resettlement program needed to slow down, lest refugees with nefarious aims be allowed in the country:

"The recent attacks in Paris are a grim reminder of the death and destruction even a small number of malevolent individuals can inflict upon a peaceful country and its citizens. Surely, we do not want to be date-driven or numbers-driven in an endeavor that may affect the safety of our citizens and the security of our country," wrote Wall in a letter to Trudeau.

- Likewise, some leaders expressed concern over the lack of specific information about the real costs involved in the policy.

- Disapproval grew particularly strong after the Paris attacks, when anti-muslim sentiment increased. Some politicians, such as the Conservative Premier of Saskatchewan, Brad Wall, stated that Trudeau’s refugee resettlement program needed to slow down, lest refugees with nefarious aims be allowed in the country:

- 6. Fortunately, Canada’s economy did not suffer any major setbacks between 2015 and 2016: in 2016 its GDP grew by 1.6 percent in comparison to the previous year. Likewise, it did not suffer from a natural disaster or enter any wars. The refugee policy was not affected by this condition.

Footnotes:

- ↑ In the private sponsorship program, a group of individuals commits to provide financial, housing, social, and psychological support to a refugee(s) for approximately one year.

- ↑ In the Blended Visa Office-Referred program, the UNHCR matches refugees designated for resettlement with a private sponsor in Canada.

- ↑ A horizontal initiative refers to situations wherein two or more federal organizations collaborate on a common policy under a formal funding agreement.

The First Arrivals

The first plane carrying 163 refugees arrived in Toronto on December 10, 2015. They were greeted by Prime Minister Trudeau, other government officials and some media outlets. Some of the refugees would stay in Ontario, while others would go on to Alberta and British Columbia. Other planeloads would arrive throughout the following months, with the first 10,000 refugees landing by January 13, 2016.

The remaining 15,000 refugees would arrive by the end of February, 2016. The 25,000 people would be a mix of privately sponsored and GARs. Evidently, the Liberals were unable to keep their promise of bringing 25,000 refugees by the end of 2015.

Settlement and Integration throughout Canada

The final destination of many refugees was a result of a matching process, wherein the Resettlement Operations Centre in Ottawa collaborated with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to learn more about the background and needs of refugees, where they might have family or friends in Canada, their medical needs and the availablility of settlement services. The majority of Syrian refugees went to Ontario, followed by Alberta and British Columbia.

The federal government’s main goals for supporting settlement and integration centered around housing, language training and jobs. The government’s Resettlement Assistance Program ensured the provision of basic services to refugees around the country as well as one year of basic income support. Once the first year passed, refugees would be eligible to receive provincial social assistance support.

The government worked with provincial and city governments, as well as over 500 service provider organizations across the country to carry out the settlement and integration aspects of the refugee policy. These organizations, which received funding from the IRCC, supported refugees with services such as language training, job seeking, gender and age-based support, and related.

As Dawn Edlund, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, IRCC, noted,

“There is a really strong partnership between the federal government and our settlement-providing organizations, and we're learning lessons from them every day and identifying with them the gaps they're seeing on the ground…and then making sure we get the money addressed towards those gaps.”

In Canada, the federal government and the IRCC have agreements with each provincial or territorial government that determine how each is to share on the responsibility for immigration and refugees. For example, in British Columbia, while developing annual intakes for refugees and immigrants, the federal government will take into consideration the provinces’s own annual targets and objectives. Many provinces such as Manitoba, Ontario and British Columbia, began to take initatives to support the integration of refugees as early as September 2015. Manitoba pledged $40,000 to help settlement organizations support hundreds of additional refugees, while British Columbia committed to $1 million towards trauma counselling, job placement programs and the recognition of foreign credentials.

Cities throughout the country collaborated with local settlement agencies to welcome and help settle refugees. In Vancouver, Mayor Robertson worked with the Immigrant Services Society of BC (ISSofBC) and the Mayors of Coquitlam and Surrey to help Syrian refugees as they settle. Likewise, in Calgary, Mayor Nenshi supported the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society in coordinating resettlement initiatives.

A Rapid Impact Evaluation was conducted in late December 2016 to assess the impact of the refugee policy. It found that, though the initiative had been largely a success, there were some areas for improvement, including:

- The need for end-to-end comprehensive planning, including settlement considerations, by the IRCC

- The need for accurate and timely provision of information regarding refugees to IRCC staff, partners and stakeholders

- The provision of a pre-arrival orientation to refugees prior to arriving in Canada

Four Years Later

For many Syrian refugees who had arrived in Canada in December 2015, December 2018 was an important month. Many newcomers had by then spent 1,095 days in Canada which meant that, after passing a language proficiency exam, they would be eligible to apply for Canadian citizenship.

However, according to immigration advocates many challenges remained for refugees, including poverty, learning English or French, and paying for the citizenship application ($630 per adult and $100 per child). For example, of the approximately 1,700 refugees who arrived in Nova Scotia in 2015, 795 remained on income assistance in September 2018.

Compounding the problems related to local integration was the fact that IRCC was not properly tracking outcomes related to services and programs meant to support Syrian refugees. That is, the government was failing to track the implementation of its policies. A fall 2017 report by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) found that the federal government had failed to gather timely information on language training and had not fully implemented its strategy to measure outcomes among Syrians. Auditor general Michael Ferguson noted, “It is very much incumbent on the department to collect the information to understand what's going on at the provincial level as well because it is their responsibility to understand if these refugees are integrating.”

The OAG’s report focused on three areas: service delivery, management of information for decision making, and outcome measurement.

In terms of service delivery, the report found that most refugees had received settlement services. More than 80% had a needs assessment and 75% of people who received language assessment assisted language classes.

Results were not as positive for the management of information required for decision making. The federal government had allocated approximately $257 million for the delivery of these services, and without required information the expenditure of these funds could be problematic.

Specifically, the OAG found that IRCC did not have precise or timely information on language training necessary for managing services. Therefore, it could not monitor whether funding was being directed at the right location or if it was having a positive outcome. The report also found that contribution agreements made between IRCC and service providers did not include service expectations, leading to differing quality and inconsistency throughout Canada.

The third area of the audit, outcome measurement, also showed negative results. Although IRCC had developed an Outcomes Monitoring Framework for measuring the results of its Syrian refugee initiative, it had not collected information from the provinces for some of its indicators.

These indicators include variables such as access to health care and education, income assistance, and housing.

IRCC agreed with all of the report’s recommendations and set about carrying out a series of changes and adding new plans and programs for the adequate delivery and monitoring of its services and programs.

Local integration is a continual process. Like many other articles, a May 2019 article published in MacLean’s profiled a Syrian family that faced challenges yet continued to work hard to find their way. The mother of the family, Baraa, chose to attend English classes at a local church, while her husband, Jehad, chose to work in order to gain more independence and pay the bills.

The same article described results from a StatsCan report indicating that, after 15 years in Canada, refugees from certain countries had incomes that were very similar to those of immigrants. However, other refugees from other countries appeared to fare a lot worse. It is still too early to tell how Syrian refugees will do in the long term. Bessma Momani, professor at the Balsillie School of International Affairs, is hopeful for Syrians in Canada: “I think we’ll see a lot of new small businesses coming out of this group of Syrian refugees. I suspect by the next census, the numbers [of employed Syrian refugees] will have greatly improved.”

In June 2019, the Research and Evaluation Branch of IRCC published the executive summary of the Syrian Outcomes Report, which provides an overview of the integration outcomes for Syrian refugees resettled in Canada between November 2015 and December 2016. The results indicate that “Syrian integration outcomes have been steadily improving since their arrival in Canada. Syrians are getting the help they need. They feel welcome in their communities.” Other outcomes reported include increasing rates of employment, challenges with social and linguistic barriers, and having enough information to carry out their day-to-day lives. The full report will be released in October 2019.

Sharing Permission

When reusing this resource, please attribute as follows: Susanne Beilmann.

|

|