Documentation:Gharial

Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) Conservation: Status, Challenges, and the Future

Gharial crocodile originated in the Indian subcontinent and have a mostly pescatarian diet and are predators underwater.[2] Its distinguishing characteristics include an elongated, narrow snout and lots of interlocking teeth lining the mouth. Amongst some of the largest crocodile species, it can reach up to 20 feet in length. In addition, they are categorized as critically endangered on the conservation scale.[3] There is an estimate of less than 250 adults left in the wild. The cause of this species' declining population is habitat modifications through water damming and water extraction. They are also impacted by the fishing industry in two main ways. Firstly, the lack of prey due to overfishing, and second being caught accidentally in gill nets.[4] Gharial endangerment is not only harmful to themselves but also to the ecosystem. We are going to focus on the causes and effects of the Gharial conservation status and the conservation efforts made by the government of India and other surrounding organizations for the protection of the species.

Gharial Origins

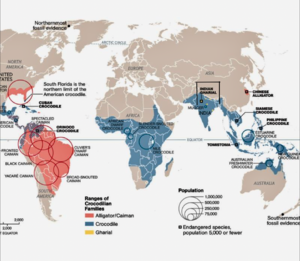

The Gharial crocodile species is considered to be one of the most rare and most aquatic of all crocodilians. This species is classified as a keystone species running back around 65 million years in age. It originates from the Gavialidae family and is a part of the Gavialis genus. The Gharial crocodile is one of the oldest crocodilian species known. The crocodile's name, Gharial, is derived from the Nepali/Hindu name “Ghara”, which stands for ‘earthen jar pot’ .[5] In past years, the Gharial crocodile could be found in the rivers of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. However in more recent years due to it’s mass decline in population size, the rest of the species remain solely in Nepal and northern India.[3]

Gharial Physical Characteristics

Gharials are one of the two species in the Gavialidae family. The Gharial physical characteristics consist of olive skin colour, elongated snout and jaw features interlocked teeth that are particularly sharp. The sharpened teeth allow the predator to strike and capture the prey within the water.[3] The gharial’s tail is wide and flat, with webbed feet which help propel the Gharial through the water. Relative to facial characteristics, the body of the gharial is one of the largest among the crocodilian species. On average the Gharial is around 4.75 metres in length as well as the gharial reaches sexual maturity around 3.5 metres.[6] With such considerable length, the gharial can weigh up to 2,200 pounds.[6] The gharial average life span is approximately 40 to 60 years.

Male vs. Female

The Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus, has many physical and behavioral differences between males and females. Males tend to range from 5 to 6 meters in length while females are must smaller ranging from 3.5 to 4.5 meters. One of the most distinguishable characteristics to depict the species' gender is their snout. Male Gharial have a bulbous growth at the very tip of their snout called the “ghara.” Its functions are to protect the nostrils, act as a vocal resonator, and create a loud buzzing-like noise. In addition, this physical characteristic is a physical indicator for female Gharial for mating. Similar to most crocodiles, the Gharial species are polygamous. This means that they have one singular male that defends a territory containing multiple females. Some of the males' territorial behaviors include head slapping and using their ghara to vocalize.

At sexual maturity, females reach a length of about 3 meters and males at about 4 meters. Mating usually occurs between the months of December and January. A couple of months later, during March and April, female Gharial crocodiles dig their nest depositing around 40 eggs. These end up hatching on average 70 days later with the protection of their mothers as the eggs require incubation. [3]

Diet

The Gharial is a carnivore reptile that predominantly consumes a fish-based diet.[6] Attributed to the Gharial elongated snout and interlocked sharp teeth, the predator can capture prey swiftly. The means of capturing is done through striking the fish through rapid sideways sweeps, then impaling the fish. Although the Gharial primarily consumes fish, they also consume crustaceans, a group of anthropoids, as well as soft-shelled turtles. [6] As the gharial reaches full maturity their significant stature has the full capability of impaling most aquatic animals, however with maturity comes a more selective diet.

The juvenile gharial diet consists of insects, tadpoles, fish, crustaceans, and frogs.[6] Regarding the juvenile Gharial's physical characteristics, they have a greater variety of food selections more accessible to them than a mature gharial.

Conservation Status, Issues, & Challenges

Endangerment and Its Causes - Conservation Status

These reptiles face a multitude of threats to their existence. The main ones include habitat degradation, dam construction, and hunting. For instance, in the 1970s, they were close to extinction and remained on the endangered species list. Since they rely on waterways, river damming is changing their natural habitat due to their inability to walk on land. Hence, they are unable to find other habitats where the water is not dammed, and this limits their chances of finding new habitats.[7] Additionally, they are impacted by fishing in two main ways: lack of prey due to overfishing, and accidental capture in gill nets of adult and subadult individuals. They are also persecuted by local fishers, who hunt their ‘ghara,’ or penises and fat for use in traditional medicine.[7] The local tribes also collect their eggs for food which makes them more endanger as no offspring able to survive.

The Gharial species has less than 200 in India, less than 35 adults in Nepal, and the species located in Pakistan is merely non-existent. The decline has been attributed towards trophy hunting of the body and skin, as well as egg collection. Withal, hunted for traditional medicinal purposes.[8]

The main concern is irreversible habitat loss, as a result of conduction of dams, artificial embankments, and sand mining.[8] Furthermore, the ratio of sex population is attributed to the decline, as approximately the ratio of male is 1 to 10 of females. As a result of the disparity of males, it is an issue affecting population growth.[8]

A limitation among the conservation status is the lack of quantitative population estimates of the last three generations, causing the exact rate of decline problematic.[8]

Relationship with Ecosystem

The Gharials’ main habitat is in large rivers, so many of them reside in spanned rivers in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. However, due to deforestation, they live in fragmented populations in Nepal and northern India. A study showing the genetic assessment of the gharial shows low populations in the regions of Chambal and Girwa.[9] Since the genetic diversity of a species is influenced by the geographic range, abundance, demography, and life-history traits, there is lower genetic diversity for some populations. For example, the narrow-ranging and less abundant species with a demographically challenged population have a lower genetic diversity when compared with widely distributed, abundant species with a stable demographic history.[9] This is a crucial factor to consider when thinking of conservation solutions.

They are a keystone species for freshwater ecosystems. For instance, they help bring nutrients from the bottom of the riverbed to the surface.[10] This increases primary production as well as fish populations, preventing trophic cascades. Nonetheless, habitat loss and intensive fishing exists and destroyed their native habitats and livelihoods.

Conservation Challenges [11]

Multiple conservation challenges occur for wild Gharial due to their unique living habits. Some geographical issues that may lead to the loss and degradation of Gharial’s habitat include dams, pollution, and exploitation of gravel and sand. First, building a dam across the river will restrict fish passages and thus, reduce prey species for wildlife, including Gharials. Additionally, the dam changes the geological environment for species dispersal and habitat which causes a negative effect on the river’s biodiversity and ecosystem. Moreover, the dam controls and affects the water flow of the river which could harm the water quality and humidity of the river. Nevertheless, pollution due to industrial wastes and chemical deposal could also harm the water quality of the river. Last but not least, increasing the volume of gravel and sand because of commercial developments and fishing activities would deteriorate Gharial’s habitats. On the other hand, some challenges are due to anthropogenic activities, such as the depletion of the Gharial population. In summary, most of these conservation challenges are developments or activities that change and harm Gharial limiting their nutrient resources and habitats.

Conservation Efforts & Solutions

Government Conservation Efforts [11]

Nepal's government acknowledged the importance of Gharial in 1973. They are one of the protected species listed in Nepal's National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act (NPWCA). A significant report from the Nepal government is the Gharial Conservation Action Plan (GCAP) in 2018. It adopted provisions from the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (2014 to 2020), Forest Policy (2015), and Protected Area (PA) management plans. The GCAP was also developed based on relevant literature, field assessments, and consultations. In the GCAP document, it has addressed various conservation actions and programs within the country. First, the Nepal government launched a Gharial Conservation and Breeding Center (GCBC) at Kasara. This center contributed to the construction of Gharial breeding pools, health laboratories and fish farms. These infrastructures are used for Gharial’s in-situ conservation and reintroduction program through activities like egg collection and captive rearing of hatchlings. As mentioned above, Gharial’s endangerment is partly due to their egg being stolen. Thus, a Gharial Monitoring Center (GMC) was established. The GMC hires nest watchers to guard Gharial nests from the wild in the center and GCBC. In addition, they also monitor wild Gharial nests. As a result, GMC successfully increased Gharial survivorship to 80% and released them into nature. The Nepal governance not only conserved the local Gharial species but also internationally from ex-situ conservation. For instance, several Gharials are given to countries like Japan and France. Furthermore, through ex-situ conservation, Nepal learns new conservation strategies on incubation, rearing, and releasing Gharial.

With all these conservation programs and centers, Nepal is making great progress. Starting in 2008, Nepal has started monitoring Gharials populations in the Rapti, Narayani, Koshi, Karnali, and Babai Rivers. These data show Gharial conservation success from the increasing number of Gharial population.

Other Conservation Efforts

In the 1970s, Gharial came close to extinction and even now remain on the endangered species list. Environmentalists cooperated with the government to find solutions, and this has led to some reductions in disappearances. In 1970, there was full protection granted in the hopes of reducing poaching losses. Although these were slow to implement at first, there are now 9 protected areas in India.[12] Additionally, other methods were captive breeding and ranching operations. Eggs are collected from the wild, raised in captivity, and then released back into the wild. Through this program, more than 3000 animals have been released into the wild.

Conservation Solutions

The Los Angeles Zoo and the Wildlife Trust of India have paired to enact conservation efforts in gharial populations through releasing hatchlings back to the river safely.[13] Although it has yielded positive results and around 217 gharials were spotted back in the river, the method of ex-situ conservation sparks debate. Removing a species from their natural habitat and reintroducing it back into a new habitat with similar conditions may pose risks if the species is not well adjusted. There may be technical and social complications when the species is residing in a zoo. A better move forward would be to conduct research on animal adaptabilities before trying this method and face potential negative effects. It is controversial despite the method being important towards increasing populations.

The Nepal government restricts fishing of gharial in order to protect populations. However, the Indigenous Bote people demand their right to continue fishing on their lands which serves as their tradition and source of income. Even government-provided funds and resources will not offset the consequences of restricting fishing.[14] It poses economic and social challenges for communities whose livelihoods depend on fishing. Not only is it their source of income, but the river is their origin. Furthermore, there should be other measures that does not require fishing restrictions. For instance, reducing pollution and sand mining in the river upstream can help protect the species instead. It is important to consider holistic aspects when making decisions.

- ↑ "Gharial Map".

- ↑ "Gharial: a pescatarian crocodile species as old as the dinosaurs".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute".

- ↑ "GHARIAL Gavialis gangeticus".

- ↑ Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation . (2018). Gharial Conservation Action Plan for Nepal. Gharial Cover.Indd; Government of Nepal. https://wwfasia.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/gcap_report_2018.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Gharial, facts and photos".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Status of the Critically Endangered gharial Gavialis gangeticus in the upper Ghaghara River, India, and its conservation in the Girwa–Ghaghara Rivers".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Gavialis gangeticus, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Microsatellite analysis reveals low genetic diversity in managed populations of the critically endangered gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) in India".

- ↑ "Gharials Under Grave Threat".

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Gharial Conservation Action Plan for Nepal" (PDF).

- ↑ "Gharials, most distinctive of crocs, are most in need of protection, study shows".

- ↑ "L.A. Zoo to ink pact with Bihar Govt., Wildlife Trust of India for gharial conservation".

- ↑ "Gharial Conservation Plan leaves Nepal fishing communities searching for New Jobs".