Documentation:Case Study 3: Ethnobotany

Case Study 2: Ethnobotany

Case Study Details

| How to use this Case Study | |

|---|---|

|

1. Read the Case Study Details and Introduction section. | |

Case study campus food asset: Plants on campus.

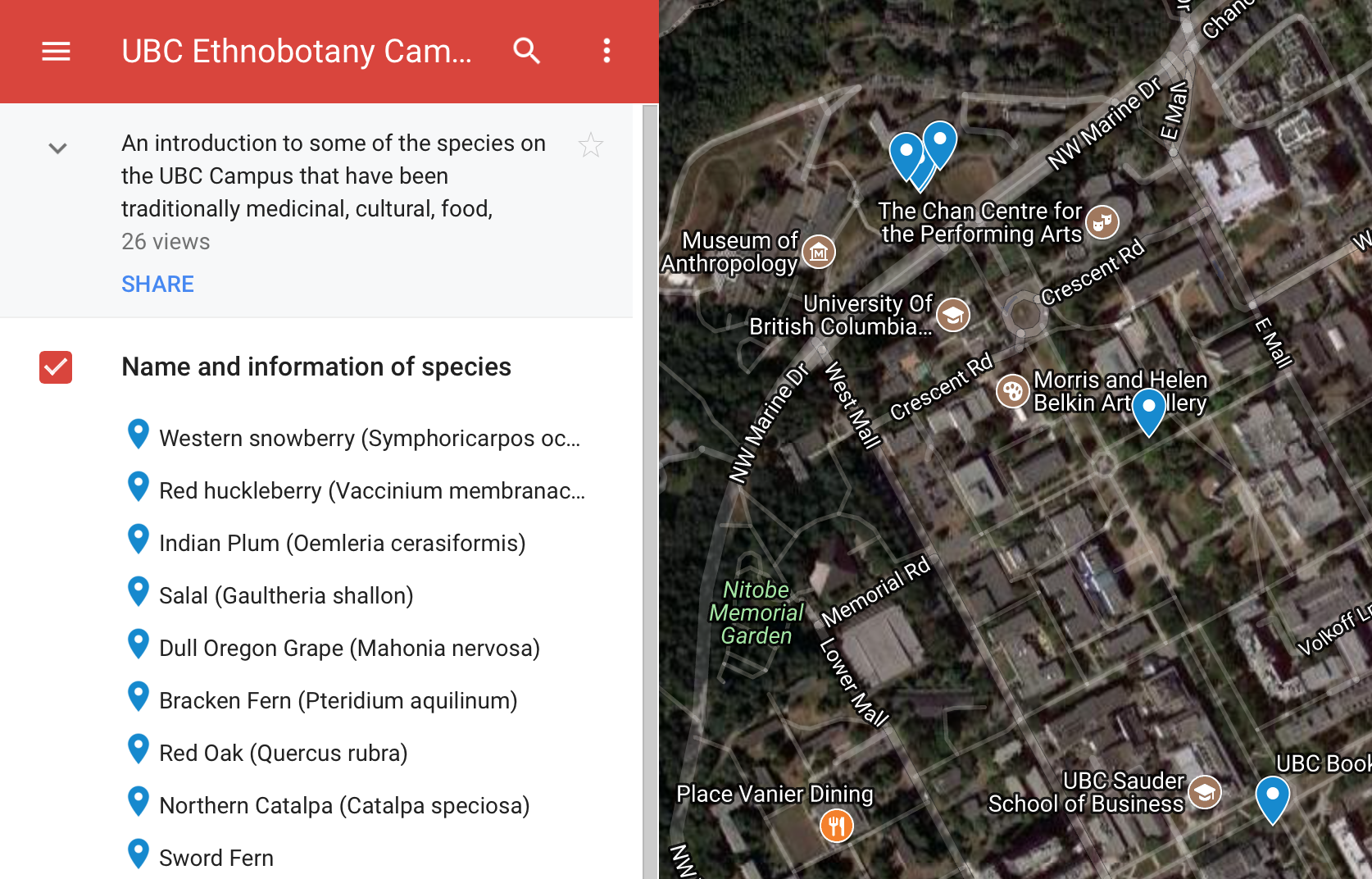

Case study location: UBC Vancouver campus (follow Google Map Tour).

Case study timeline: Publically accessible all hours of the day.

Case study topics: Fine Arts, Landscape Architecture, Media Studies, Political Science, Forest Policy, Medicine, Kinesiology, Biology.

Ethnobotany Plant Tour

It is hard to turn a blind eye to the beautiful landscaping at the UBC Vancouver campus. While many plants species are present, only a select few are native to British Columbia. The Ethnobotany Plant Tour highlights some of these native species on campus that have historical medicinal, cultural or food uses. Give yourself 2 hours to complete the tour - some plants are small and more difficult to spot. Refer to the images on the Google Map Tour, but remember, it may be a different season and the plant could look different!

Link to Ethnobotany Plant Tour, on Google Maps: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=17kZVsUhDoNF8Kec8yjNZna2xZwU&ll=49.266619192497075%2C-123.25192253729551&z=16

Case Study Introduction

The University of British Columbia aims to advance knowledge through research, teaching, and community engagement. Innovations and emerging areas of excellence are constantly explored to move forward, towards where nobody else has been.

Ethnobotany is the study of the relationship between plants and people. The word ethnobotany is the combination of the Greek root ethno, meaning ‘people’ or ‘cultural group’ and botany, meaning ‘plants’. The field involves a spectrum of inquiry, from the archaeological investigation of ancient civilizations to modern bioengineering. It relies on a multidisciplinary approach involving anthropology, archaeology, botany, ecology, economics, medicine, religion, amongst others.

There are thousands of trees, shrubs, and understory plants native to British Columbia that have historically been used by Indigenous people to aid in every aspect of life. The introduction of non-native species—through human-driven colonization—has had a severe impact on peoples’ traditional relationships with plants. Our relationship with plants is no longer what it used to be.

This case study aims to explore the benefits of engaging with traditional knowledge, specifically the traditional knowledge that lies in the relationship between plants and people. There exist on-campus initiatives that help keep our relationships to plants alive including the Campus Botanica, an interpretive plant sign project that engages passersby with culturally diverse ways of seeing and relating to plants; as well as the Indigenous Research Partnerships ethnobotanical plant database.

The geographic centre of this case study is the UBC Vancouver Campus, its landscaping, ornamental gardens, acres of lawn, and endowment . These should be centre-of-mind when engaging with the materials below.

As stated by Alice Walker (the first African-American woman to win a Pulitzer Prize), “I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don't notice it.” Perhaps the same can be said for not noticing plants in general. Consider this case study and tour as form of rapprochement!

Pathway #1 - Landscaping, Design and Ethnobotany

Subjects: Fine Arts, Landscape Architecture and Media Studies

Gardens are intrinsically appealing and beneficial to humans. They are sometimes designed to better reflect the spiritual and physical use of the space by its current or past community members. They can also follow ethnobotanical attributes: adheres to a clearly defined mission, tells a compelling story, provides and an environment conductive to learning and adapts through time (Jones and Hoversten, 2004). Depending on the history, geography and culture of a place, a ‘successful’ ethnobotanical garden may greatly vary in its design. Jones and Hoversten (2004) offer the following questions for ethnobotanical considerations in landscape architecture: (1) What people/culture is being interpreted? (2) What was their relationship to this place/this site/this area?; (3) What processes are interpreted?; (4) What products are interpreted?

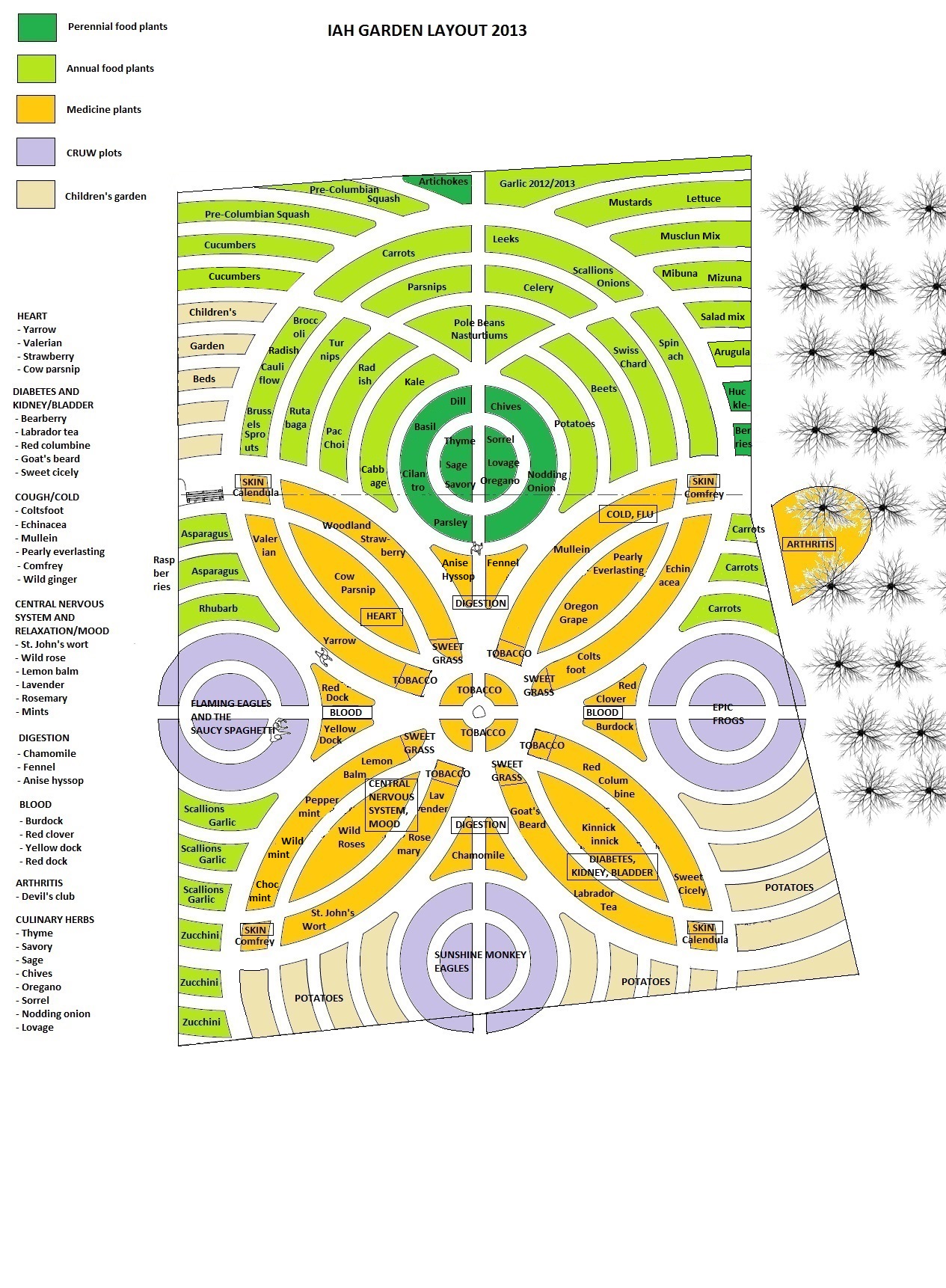

Ethnobotany is often at the centre of the design process for healing or health gardens. In 2013, the Aboriginal Health Research and Education Garden at the UBC Farm was redesigned to better reflect local Aboriginal and ecological principles. The shape and physical design of the garden incorporated a medicine wheel at the centre of the space. The inclusion of traditional native plants used for medicinal, food, fibre and dying purposes was guided by the insights and deep knowledge of the Medicine Collective, a group of Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers (UBC, 2016).

| Examples of Health Areas and Plants used for Medicine | |

|---|---|

| Diabetes: Bearberry, Labrador tea, Red columbine, Goat’s beard

Heart: Yarrow, Valerian, strawberry, cow parsnip Digestion: Chamomile, Fennel, Anise hyssop | |

Beyond the UBC Farm and the UBC Botanical Garden, landscape design on the UBC Campus acknowledges the traditional relationship between plants and people on this land. In courtyards and sidewalk plant beds, many plants with ethnobotanical purposes have been incorporated in the landscape.

Required Reading:

Suvajac, A. 2013. Institute of Aboriginal Health Garden: Design Process Summary Text

(currently on Farm Server - upload online, or attach to website)

- This document summarizes the design process for the new Aboriginal Health Garden at the UBC Farm. It provides details of the goals and considerations for the space, which were deeply informed by the knowledge from elders and community members.

Questions:

- Are plants with ethnobotanical purposes well suited to the campus landscape? Do they seem out of place? Is there a more suitable location on campus?

- Would more interpretive signage create a more meaningful learning experience? Or are these plants highlighted in the tour better left incorporated into the general landscape?

- Why are plants hidden in plain sight?

Pathway #2 - Governance and Ethics

Subjects: Political Science, Forest Policy

The discipline of ethnobotany has emerged as an important informant in federal and provincial policy decision around Indigenous Peoples’ land rights and titles in Canada. In June 2014, Aboriginal title on land was declared for the first time in Canada. The ruling by the court granted the Tsilhqot’in Nation the full Aboriginal title for the grounds their people exclusively used at the time when the Canadian government staked its claim. How did the Tsilhqot’in prove the extent of their land ownership? Partly through ethnobotanical investigation.

The study of how enthnobotany can be applied to policy development, planning, and decision-making is at the forefront of Dr. Nancy Turner’s emerging research. Demonstrating people’s dependence on plants for their well-being and their absolute need for ecosystem integrity in their territories can be a compelling approach to contest intrusions from the Crown (Turner, 2015). Research around traditional management of plants and landscapes is now, more than ever, a priority to ensure that Indigenous people in British Columbia are recognized as cultivators of the land and they can maintain or gain right to their land under the Canadian government land claim criteria.

Watch:

Introduction to Nancy Turner’s Indigenous environmental knowledge & environmental values in land use planning project

Required Reading:

Turner, N., and Lepofsky, D. 2013. Conclusions: The Future of Ethnobotany in British Columbia. Retrieved from

http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/bcstudies/article/viewFile/184543/184180

- The authors consider the modern state of ethnobotany in British Columbia, which strives to integrate Western and non-Western knowledge in effective and respectful ways. Case studies explore plants role in education, the importance of Indigenous foods, and learning opportunities for plants in healthy diets.

Additional Reading:

Ray, A. J. 2015. Traditional Knowledge and Social Science on Trial: Battles over Evidence in Indigenous Rights Litigation in Canada and Australia. Retrieved from

http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1221&context=iipj

- This article explores how traditional knowledge and oral history poses numerous challenges in Aboriginal claims litigation including how and where this information can be presented, who is qualified to present it, questions about whether this evidence can stand on its own, in Canada and Australia.

Questions:

- What role do young people play in the future of ethnobotany? Are they equipped to incorporate traditional plant uses into decision-making?

- How can we raise the profile of traditional plant uses to achieve a more well respected profile to inform provincial and federal policy? What role could the university play in achieving this?

- What are key components in code of ethics before research is undertaken relating to cultural knowledge and practices in ethnobotany?

- What are the barriers to referencing ethnobotanical uses in the court of law?

- How might other challenges involving environmentally damaging activities in the face of climate change benefit from the study of ethnobotany?

Pathway #3 - Medicinal Ethnobotany

Subjects: Medicine, Kinesiology, Biology

Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal knowledge has been preserved through the ages in written or oral form. While some of this traditional knowledge (e.g., for herbal medicine) has been incorporated into Western medicine (Fakim, 2006) and research of plant resources in traditional medicine has intensified with the aim of finding new cures for different health conditions (Wachtel-Galor & Benzie, 2011), chemically synthesized drugs, in many parts of the world, have been prioritized as the main way to revolutionize health care.

Throughout history, Indigenous peoples were coerced into abandoning their cultural beliefs and practices in relation to health care upon the arrival of settlers. Their loss of control over the land base and all of its resources was a part of the plan to systematically destroy Aboriginal knowledge and culture systems (Obomsawin, 2007). It is only recently that there has come an increased recognition by the scientific establishment that traditional healers were highly gifted persons, subject to years of exhaustive training, and whose understanding of nature and the workings of the human body-mind complex surpassed that of western science (Coombs, 2007).

Today, the challenge lies in sharing traditional medicinal knowledge across cultures. Posey and Dutfield (1996) argue that the ethnobotanical literature (journal articles, databases, and field collections in particular) serves as a major source of information and ideas for researchers and industries with commercial objectives. End users of this information are often third parties who have had no direct contact with the indigenous communities whose knowledge they are appropriating (Barnett & Banister, 2000). To counterbalance this tendency, medical professional and Indigenous healers need to create a space for dialogue and knowledge sharing. At UBC, the Indigenous Research Partnerships (IRP) aims to further develop research and education on areas of shared priorities between the Indigenous community and the university. The support of knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange from an Indigenous lens can help to stimulate innovating research in the field of medicine.

Required Reading:

Ellison, C. 2014. Indigenous Knowledge and Knowledge Synthesis, Translation and Exchange: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from

http://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/en/publications.aspx?sortcode=2.8.10&publication=127

- This discussion paper examines the theory and practice of knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange (KSTE) within public health in Canada. The author acknowledges that Indigenous knowledge can work with existing methods and theories of knowledge translation, but also requires its own KSTE process.

Questions:

- What are the costs and benefits of allowing knowledge of plants and their functional biomedical components to fall under intellectual property rights?

- What alternative models or examples exist that acknowledge and properly attribute traditional knowledge in the development of new medicinal products?