Courses:PHYS341/2021/Project9: Flute

By Sebrina More (Phys 341 project, 2021)

Flutes are one of the oldest instruments in the world, with fragments of a Neanderthal bone flute found in Cerkno, Slovenia, which date back approximately 43000 years. The flute family contains end-blown flutes, which are played vertically like the modern-day recorder, and transverse flutes, which are played horizontally like modern concert flutes. They are a member of the woodwind family; though, unlike other woodwind instruments which use reeds, they are played by blowing an air jet over an embouchure hole.[1]

History

Early flutes were a single length of bone or cane and end-blown, with six holes carved in the body. A scale could be played by lifting the fingers off the tone holes to shorten the length of the flute and get higher notes. The modern flutes we play transversely today have their roots in the first and fourth century BC. Like the end-blown flutes, they were mostly made of a single length of cane and had six holes that could be covered and uncovered to go up or down the scale. Higher notes could be achieved with cross-fingering, where combinations of holes were left open between covered holes. To achieve a wider range of possible notes, they were made in varying sizes. By 1660, they were constructed with 3 joints: the head joint, the body, and the foot, which contained an extra hole to make playing D # possible. The largest change came in 1847, by Theobald Boehm. He transitioned to metal joints and used springs and levers to eliminate the need for cross-fingering and allow for more keys to be opened or closed, which allowed for them to be arranged based on acoustic criteria rather than ease of playing.[1]

Basic Flute Overview

Flutes range in size from the 12 1/2 inch long piccolo to the 5 1/2 meter long subcontrabass flute, which is is the largest flute used in flute ensembles[2]. The overall size of the flute determines the lowest note it can play, so the varied length of the flutes allows for a range that extends from C1 with the subcontrabass flute, to C8 with the piccolo, depending on the experience of the players.[3] The most recent addition to the flute family is the Hyperbass flute [4], commissioned for Roberti Fabbriciani, which is over 15 meters long and the lowest note it plays is a C0, outside the range of human hearing, at 16Hz.[5]

Construction

Most modern flutes, especially those used for orchestras, are made of metal. The cheaper options are silver-plated brass or nickel silver. The expensive flutes used by experienced players are often made of more precious metals such as sterling silver, gold, or platinum, though there is debate as to whether these affect the tone of the flute. A study conducted by Widholm tested 7 types of flutes, ranging from silver coated to solid platinum, to see if there was a measurable difference in sound quality. The findings showed no evidence that the material of the flute affected the range of the instrument and that the individual players had the largest effect on the sound.[6]

Most concert flutes have a C foot, which means the lowest note that can be played is a C4 when all the tone holes are closed. B foot extensions can be used in place of a C foot, and drop the lowest note to a B when all the tone holes are closed.

Flutes are constructed to be open-open tubes, meaning they are open to the air at both the embouchure hole on the head joint and the end of the instrument. The head joint contains a cork at the end, which can be pushed in or pulled out to adjust the amount of space from the end to the embouchure hole. This extra space acts as a spring when the air in the tube is compressed due to an increase in pressure, and bounces back when it is compressed against the cork.[7] Blowing over the embouchure hole will create an air jet to drive oscillations of the air inside the flute. When the air inside the flute moves toward the head joint, it creates an increase in pressure which deflects the air jet. When the air inside the flute moves away from the head joint, it draws air from the air jet inside the flute, providing continuous energy.

Alignment and Tuning

Alignment

The correct alignment of the joints of the flute depends on the individual players. Jaw and chin shape, alignment of the mouth on the embouchure hole, and hand size will all affect the exact position of the head joint. The basic technique for aligning the joints is to have the center of the embouchure hole aligned with the first big key on the body of the flute.[8] Some beginner’s flutes will have lines engraved on the head joint and a notch on the body which can be aligned to help with the initial positioning, see figure 1. From this position, the head joint can be rotated to a comfortable playing position.

Tuning

Once the flute is correctly aligned, it can be tuned by adjusting the length of the flute with the head joint. The head joint can be pressed further into the body or pulled farther out to lengthen the tube. Pushing the head joint in will shorten the length of the tube, which will increase the frequency of the sound waves. Pulling the head joint further out will increase the length of the tube, which lowers the frequency. Matching a note to the frequency of a tuning fork or tuner will determine how much to adjust the flute joints.

The internal tuning of the flute uses a cork positioned at the end of the head joint. If it is too far from the embouchure hole, the high notes become flat while the low notes become sharp, and the opposite is true if it is positioned too close to the embouchure hole.

Playing Technique

Playing position

The concert flute is held horizontally, and at a slight angle to allow the instrument to stay balanced in the player's hands. Flutes larger than the bass flute are held vertically and balanced on a peg due to the size and weight of the instruments. The position of the mouth on the embouchure affects the quality of the notes, and needs to be adjusted for various notes using a technique called 'lipping'.[7] The flute is rotated toward or away from the mouth so that the lips cover different amounts of the embouchure hole to help increase the speed of the air jet. The lowest note on a concert flute is a C4, and is played with all the keys pressed down. Successive notes are played by lifting fingers off the keys or opening other tone holes to shorten the length of the instrument.

Notes and Harmonics

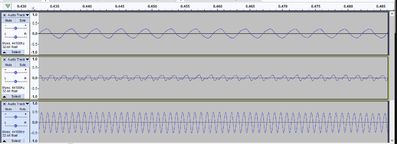

High and low notes differ in both the fingering of the keys and tension of the mouth. Boehm’s design of the flute created more tone holes than fingers available to cover them, which was compensated for by a series of springs and levers, allowing for some keys to control the closing of other tone holes along the body of the flute.[9] The higher notes have more complex fingerings, with many open holes between the closed ones, the difference is shown in figures 2 and 3. This is called venting, and it opens up points along the flute in specific locations to force higher harmonics to resonate. Unlike the lower frequency notes, the air in the flute does not escape through the closest open hole. Instead it travels the length of the flute, and the open tone holes act as a high pass filter. Some notes may be played with the same fingering, but using a technique called overblowing, in which the lips are tensed and drawn back slightly to create more air pressure, in order to achieve higher frequencies[7] shown in figure 4. To play a C4 the lips are relaxed and a gentle air jet is blown over the embouchure hole. The flute is rotated toward the bottom lip so that it covers the embouchure hole slightly. Incorrect alignment of the lip position results in breath noise instead of a musical tone. C5 and C6 are played with the same finger positions, but with varied tension on the lips. A C5 is played with the lips tensed slightly and the the bottom lip covering the embouchure slightly. C6 is played in the same position, but the lips are drawn back further and the air jet is produced with more force, shown by the higher amplitude of the oscillations compared to C4 and C5.

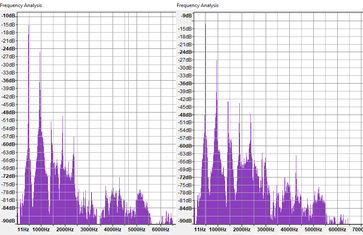

Some notes also have multiple fingerings, such as A♯/B♭, which close different keys depending on the finger placement. These have little effect on the actual fundamental frequency of the notes, and are primarily for ease of playing and allow the player to transition between notes more efficiently, shown in figure 5. Both have fundamental frequency of 476Hz, as well as the same higher harmonics afterwards at 950Hz, 1423Hz, and 1899Hz. The spectrogram on the right, however, has more breath noise and third and fourth harmonics are slightly louder than in the spectrogram on the right.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Flute History. (n.d.). Gemeinhardt. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from http://www.gemeinhardt.com/connect/gemeinhardt-education/flute-history.html#:%7E:text=A%20flute%20dating%20back%20to,43%2C000%20to%2035%2C000%20years%20ago.

- ↑ Jen Kramer. (2012, September 13). World’s Largest Flute: the Subcontrabass [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qmxnp_3KUt0

- ↑ Borst Jones, K. (2015, March 11). The Piccolo. School of Music. https://music.osu.edu/flute/resources/piccolo#:%7E:text=Piccolo%20Pointers&text=The%20range%20is%20from%20D5,an%20octave%20higher%20than%20written.

- ↑ Roberto Fabbriciani - Concerto per flauto iperbasso. (2012, March 7). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DaNFGhY5x9g Introduction

- ↑ Brame, J. (2020, November 10). What Is The Hyperbass Flute? Notestem. https://www.notestem.com/blog/hyperbass-flute/ I

- ↑ Widholm, Gregor & Linortner, Renate & Kausel, Wilfried & Bertsch, Matthias. (2001). Silver, gold, platinum-and the sound of the flute.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Flute acoustics: an introduction. (n.d.). UNSW. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://newt.phys.unsw.edu.au/jw/fluteacoustics.html

- ↑ How to Align a Flute Correctly! (2018, October 8). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKSaYdRcdqI&list=LL Introduction

- ↑ Wilson, R. M. (n.d.). Boehm flutes. Old Flutes. Retrieved April 4, 2021, from http://www.oldflutes.com/boehm.htm