Course:SAMPLE300/2020/Vancouver Money Laundering

The Casino Coup: Vancouver Money Laundering

“Greater Vancouver has acted as a laundromat for foreign organized crime, including a Mexican cartel, Iranian and Mainland Chinese organized crime. The region has acquired an unenviable reputation for serving as a site for money laundering, drug trafficking, and capital flight.” -- Peter M. German, Dirty Money Report[1].

In the past decade, the beautiful, coastal city of Vancouver has been shaken by an uncomfortable truth. The home of athleisure fashion and unparalleled, internationally renowned outdoor sports is a favored locale for money laundering by international crime syndicates.

What Happened? A Brief Summary

Searching for a Minnow, Finding A Whale

In July 2015, a RCMP officer told a investigator for British Columbia Lottery Corporation that police officers searching for a 'minnow' had found a 'whale'[2].

The minnow the RCMP had be tracking was a single money service bureau and a casino. Instead they learnt that in one month at a BC casino, $13.5 million had passed through its cash cages, mostly in $20 bills--the preferred currency of drug traffickers[2].

The Germans Are Coming

In response to further reports highlighting the extent of B.C. money laundering problem, the B.C. Provincial Government launched The Cullen Commission.

On March 31, 2018 what became known as "The German report" was published. Across 250 pages, the report carefully details how dirty money moved through Lower Mainland casinos. It focused on the particular failures of government regulators to identify and stop these rampant crimes[2].

The Vancouver Model

In a testimony to the Cullen Commission on May 2020, criminology professor Stephen Schneider highlighted the term "The Vancouver Model"[3]. It describes how money laundering in B.C. developed and depended upon the creation of professional organizations that specialized in the movement of dirty money.

The following Wiki page therefore describes:

A) What the Vancouver model is and how it works.

B) How the Vancouver model is facilitated by certain factors and circumstances unique to Vancouver

C) The role the media played in exposing money laundering in British Columbia.

For a Prezi with infographics detailing this process, click here.

Why is this Important?

Money laundering through Vancouver casinos is directly related to an increase in Vancouver real estate prices[4]. It also funds and facilitates criminal activity in the city, therefore enabling the opioid crisis and gang warfare[5].

What is the Vancouver Model?

A Case Study:

Background: A Chinese national needs to move $1 million from China to Canada. However, because the CCP does not allow more than US $50,000 to leave the country, illegal methods need to be used.

Step 1: The Chinese national transfers money to the bank accounts of a Chinese crime syndicate that has illegal operations in Vancouver.

Step 2: The Vancouver arm of the gang has the equivalent in dirty cash money from illegal drug deals.

Step 3: The Vancouver gang hires a "VIP Gambler" & lends them the cash, often in the form of $20 bills wrapped in elastic bands and stuffed in a hockey bag.

Because this money is a dirty byproduct of illegal activities, it needs to be cleaned using the casino money laundering method.

Step 4: VIP Gambler will go to the casino and trade the cash for chips.

Step 5: After some time of gambling, the VIP Gambler will trade the chips back for a casino cheque. The cheque received (and its monetary value) will be cleaned of any criminal origin.

Step 6: VIP Gambler will give the casino cheque to the Vancouver gang.

Step 7: The Vancouver gang will take a cut of the money and then give the remainder to Chinese National.

Step 6: To avoid any scrutiny and get rid of the cash, it will be invested in Vancouver real estate. This is possible because identification is not required and because property can be bought with cash and using "For Sale By Owner (FSBO)" tactics which minimizes the paper trail.

- This is a case study. There are many variations on this structure. This is a case study lined out by Dr. Stephen Schneider in a testimony to Supreme Court of British Columbia[5]. But is is just a case study. There are many variations and-- given the illegal nature of these activities--many variations that are unknown.

- Schneider also stated that this was more speculative and anecdotal than empirical. However, Schneider testified that there are numerous reports to collaborate this. It is a challenge to make this model "empirical" because it all happens underground.

This is NOT an Asian Problem.

"Organized crime survives because there is a market for its product. Those who purchase goods and services from organized crime are we, the public. This is not an Asian problem...It is our problem, not China’s problem."

--- Dirty Money Report, Peter M. German. [2]

While Chinese gangs and Chinese nationals have received scrutiny for laundering money, is it important that we do not frame or understand this as a Chinese problem.

Vancouver is used as a site of money laundering for international organizations, including Mexican cartels and Iranian gangs. This is a matter of poor policy and poor regulatory oversight on behalf of the Vancouver municipal government. It is also facilitated by certain factors within Vancouver society. These poor policies and societal factors created the conditions that exposed Vancouver to international financial crime[2].

Why Does it Happen in Vancouver?

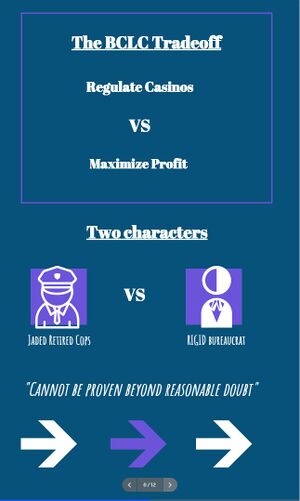

Investigative reporting and testimony from the ongoing Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia has highlighted the number of organizations and people that could have stepped in to curtail money laundering in casinos in B.C. Casino employees witnessed patrons exit the premises to retrieve bags of cash from known loan sharks waiting outside, and allowed them to continue playing.[6] The British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC) used an outdated system that they knew was not effective to track the money cycling through casinos. It took the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) years to assemble the resources to properly investigate with private investigators the severe money laundering problems in casinos, and when they finally completed an investigation, an administrative error forced the Crown to drop all charges. But the source of the dysfunction that enabled money laundering schemes to flourish in B.C. casinos for the past decade is the BCLC, and its conflicting responsibilities to regulate the gaming industry while also maximizing its profit.

It's All About the Money

The Gaming Control Act (GCA) defines BCLC’s mandate. Section 7.1 states “the lottery corporation is responsible for the conduct and management of gaming on behalf of the government.”[7] Other sections of the act give BCLC the power to set rules governing the handling of cash and security at casinos.[8] Despite this dual mandate, which assigns both security and managerial responsibilities, decisions made by the BCLC in the past decade reveal a singular focus on generating revenue, at the expense of all else.

Policy changes designed to attract “VIP” patrons, who place wagers of tens of thousands of dollars and therefore generate significant revenue for casinos, have been cited by investigators as evidence that BCLC is willing to turn a blind eye to criminal activity for the sake of profit. Investigators at the Gaming Policy Enforcement Branch (GPEB) began raising the alarm about money laundering as early as 2009. Larry Vander Graaf, the former executive director of GPEB, testified to the Cullen Commission that in 2009 he tried to convince BCLC to flag any player with more than $3,000 in twenty-dollar bills as suspicious, on the grounds that twenty-dollar bills are commonly used in the drug trade, and traffickers often carry large numbers of them.[9] Rather than heed Vander Graaf’s warnings, BCLC raised the cash buy-in limit from $145 to $9,999. By 2012, the limit for cash buy-ins had reached $90,000. These increases had the exact opposite effect that Vander Graaf was aiming for when he made his recommendations. Rather than curtail the influx of dirty money in casinos, these policy changes signalled to organized criminals looking to “wash” the proceeds of their crimes that they could do so quickly and efficiently, courtesy of BCLC.

BCLC retains about 65% of the profit they generate, which in 2016-17 totalled $1.339 billion.[10] The rest goes to the provincial government. In the past 34 years, BCLC has generated over $20 billion for the government, making it the province’s largest source of revenue other than taxation.[11] This places the government of B.C. in the same compromised position as BCLC, serving “as both a regulator and a beneficiary” of the provincial gaming industry.[12]

Just like BCLC, B.C. government officials have been accused of enabling money laundering in the province. Vander Graaf and his assistant were fired after reporting their observations of money laundering to government officials. Vander Graaf testified that he believes he was terminated because he was so vocal about the problem that the provincial government feared he would draw media attention to the issue, which would force the province to do something about it.[13] Other former GPEB investigators have accused a variety of government officials of turning a blind eye to money laundering, including former Solicitor-General Kash Heed, Associate Deputy Minister Doug Scott, and former Minister of Gaming Rich Coleman.

The failure of the GCA to separate the roles of regulatory oversight and profit generation reflects an assumption that government bodies would not sacrifice the integrity of the gaming industry for financial benefit. Unfortunately, this assumption has been proven naive by the unwillingness of BCLC and other government officials to act in the face of widespread and overt money laundering.

An Adversarial System

The Gaming Policy Enforcement Branch (GPEB) was established by the GCA as a regulatory body “responsible for the overall integrity of gaming.”[14] This short mandate has led to a lot of problems, as it fails to clearly define the regulatory role of GPEB, and how it differs from that of BCLC. GPEB has operated on the assumption that the word “overall” indicates that their authority as a regulator and investigator supersedes that of BCLC.[15] BCLC does not agree. Any time GPEB has tried to investigate or issue a directive to BCLC, they simply say that GPEB has no authority to do so, and nothing changes.[16] Therefore, what was legislated to be a complementary relationship has devolved into an adversarial one.

The relationship between GPEB and BCLC is worsened by the tension between GPEB’s investigators and the bureaucrats of the BCLC. The investigative unit at GPEB is largely composed of former police officers with decades of law enforcement experience. These investigators testified that when they witnessed plastic bags full of twenty-dollar bills wrapped in elastic bands, they immediately connected it to their experiences as police officers raiding drug operations, as traffickers almost always carry money this way.[17] Their instinct is to investigate, but they are not allowed to intervene on the casino floor. All they are allowed to do is file a report, which can only contain the basic details of the exchange.[18] Investigators are not permitted to include their professional opinion about the significance of the transactions, even when their opinions are informed by decades of law enforcement experience.[19] Further, many testified that when they filed a report, it was sent up the hierarchy to superiors, and they never heard word of it again.[20]

GPEB investigators, already hamstrung by their inability to intervene on the casino floor and frustrated by the fact that their reports were producing no results, faced the rigid bureaucracy of BCLC, which was determined to avoid addressing the money laundering issue. They argued that organized criminals would not attempt to launder money by gambling, because they risked losing some of their profits.[21] GPEB investigators struggled to argue against this point in reports which forbade the inclusion of anything other than basic observations, and BCLC continued to refuse to act until it was proven beyond a doubt that dirty money was being washed in casinos. The system ultimately worked to silence the expertise of investigators and allow BCLC officials plausible deniability.

Things did not change until 2015, when two GPEB investigators, Rob Barber and Ken Ackles, compiled all of the reports of suspicious transactions from the month of July into one spreadsheet. Through this slow, manual process, they discovered that in that single month, there had been $20 million in suspicious cash transactions. $14.8 million of these were entirely composed of twenty-dollar bills. The spreadsheet only included suspicious transactions dealing with cash amounts higher than $50,000, meaning that there could be more suspicious transactions below that amount that were not recorded.[22] Finally, the scale of the problem was laid out clearly enough to catch the attention of people in power, and investigations were launched.

Beyond the Casino

There is a general perception of white collar crime as a white collar issue. As the next section will discuss, much of the media coverage of this money laundering scheme tied it to high real estate prices and luxury car sales - largely the concerns of the rich. Meanwhile, debate rages on about how to address the opiate crisis wreaking havoc in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, and throughout the province. These two issues are rarely connected.

Every investigator that has testified at the Cullen Commission so far has recognized the structure of the laundering operation and the presentation of elastic-wrapped bundles of twenty-dollar bills as indicative of a drug trafficking operation. One of the most important catalysts of the opiate crisis has been thriving under the nose of powerful bureaucrats who looked the other way because it brought them financial gain. This hasn’t just permitted the problem to grow; it’s also sent a signal to organized criminal operations around the world that Vancouver is the place for them. If they respond to this signal, Vancouver’s longstanding social issues, such as housing inequality, the opiate crisis, and gang violence, will likely bear the impact.

How Do We Know About It? (Media Analysis)

Predominantly embodied as the fourth branch of democracy, the press chiefly imbues the role of dispensing a forum for discussion, investigating impropriety, comporting as an adversary to those overshadowing power and knowledge while defending truth, freedom, and democracy. Historically accredited to Edmund Burke, journalism's characterization as a social 'watchdog' metaphor springs from the classical liberal conception of the power relationship shared between populist governments vowing to establish egalitarian states.[23] Based on a pluralistic view of social power, the evolving watchdog theory discerns the extension of fundamental individual rights such as freedom of speech, information, and accessibility to the media. Perhaps, a plausible specimen of this ombudsman function exercised by the Canadian journalists is their investigation into the under-reported snow washing at British Columbia casinos.[24] Besides its bucolic coastal mountain setting and infamous status as Canada's corruption capital[25], for over two decades, the province has metamorphosed into a haven for illicit capital flight and money laundering[26], thereby enticing a host of transnational criminal organizations with links to China, Mexico, and Iran.

CBC & The Sting Operation, 2008

In 2004, after airing a story about loan sharks operating B.C. casinos, investigative journalists at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) filed a Freedom of Information request per the reporting obligations at The British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC) - a Canadian crown corporation offering a range of legal gambling methods. Despite massive contestation by the provincial government for four years, David Loukidelis, then-commissioner, ruled in favor of CBC. The documents eventually served as a bedrock for an investigative series discussing the scope of dirty money in casinos, published in May 2008. Subsequently, the network uncovered BCLC's failure to perform its fiduciary duty of reporting any large cash transactions to the federal agency. During 2006, as Ontario casinos reported cases worth $15.5 million, B.C. casinos reported only a fraction ($60,000) under suspicious transactions, implying that neither the BCLC nor the private contractors were keen on relinquishing their lofty revenue.

On May 8, 2008, two CBC journalists, namely, Paisley Woodward and Curt Petrovich, along with a then-intern, Teresa Tang, conducted an undercover operation to launder $30,000 from the CBC, Vancouver office at the Great Canadian Boulevard Casino in Coquitlam and the Gateway Grand Villa in Burnaby. Their plan was downright methodical – they'd plugin $20 bills into slot machines, play a couple of rounds, and then abruptly cash out, following which they'd attempt to redeem their printed voucher for a casino cheque. Consequently, the reporters swiftly laundered $24,000 into 'clean money,' thus implying an 80 per cent success rate.

CBC Expose, 2014

During 2008, as the marijuana industry assumed the principal cash generator's position for organized crime, there was a noticeable decline in offsite, illegal gaming. Subsequently, with a sharp increase in the betting limits - from $5,000 to $45,000 a hand, legal gaming further grew attractive for high limit gamblers. Despite RCMP's interchangeable priorities and scarcity of resources, the media networks continued their probe into B.C. casinos. Resultantly, on January 4, 2011, CBC's Eric Rankin revisited his earlier casino story, alleging that nearly $8 million were laundered through a casino in New Westminster and River Rock during spring and summer of 2010, thereby ensuring at least one LCTR per day. Nevertheless, both the casinos and FINTRAC denied CBC's allegations citing tourism influx from Southeast Asia as the reason for the gambling industry's tripled revenue. Inspector Barry Baxter, RCMP's designated spokesperson and then-in-charge of Vancouver proceeds of crime section, commented that his unit had grown suspicious of sophisticated money laundering activities occurring at casinos. They further discovered that women who described themselves as 'housewives' arranged the large cash buy-ins at these casinos.

Although the then Minister responsible for gaming objected to Baxter's comments, yet the network's investigation triggered a substantial review of the B.C. Lottery Corporation by the provincial government during which officials ascertained their aim of "transitioning the gaming industry away from its current state as a cash-dependent industry." [27]On February 22, 2012, after a year-long struggle, CBC successfully obtained uncensored documents dated 2009/10 through another Freedom of Information request. The documents revealed an admonition of three casinos for a sparse background check of patrons[28] bringing in large stacks of cash in addition to improper documentation surrounding possible money laundering incidents. Additionally, the network disclosed a GPEB audit of Grand Villa Casino, Burnaby containing 27 LCTR's within a month, 9 of which had "insufficient details."

Nonetheless, these financiers were permitted to gamble by merely identifying themselves as self-employed or business entrepreneurs, thus violating the federal Proceeds of Crime Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing Act. In response to the CBC story, the BCLC Director of Operation Compliance advised that in the sphere of anti-money laundering, the corporation's requirement was solely restricted to gathering the information, not verifying it. Later that year, the GPEB Investigation Director noted the RCMP's incapability to initiate investigations into Lower Mainland casinos, ensuing which a total of $88.7 million (68% in $20 denominations) were reported in SCT files, thereby outstripping the most pessimistic estimates.

CTV Expose, 2014

In April 2014, Mi-Jung Lee, a reporter at CTV Vancouver, uncovered a detailed report on rampant money laundering in B.C. casinos, including comments from a former casino employee and retired RCMP superintendent, Garry Clement. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2014, a whopping $118 million were accounted for in SCT's in B.C. casinos, with 76% being in $20 bills – a common currency used to purchase street drugs, thereby signaling a steady increase and a systemic failure of the GPEB to curtail the SCT fact pattern. Shortly after the CTV expose, in October 2014, CBC News further unveiled a mysterious $27 million (packed in $20 and $50 banknotes) flowed through the Starlight and the River Rock, during spring. [29]Following the CBC expose, the Ministry of Finance issued a press statement asserting its implementation of traceable cash alternatives in addition to reiterating that the investigation jurisdiction laid with the police. Conceptually, this held; however, there was no police investigation in reality, and dirty money still rolled in.

The E-Pirate Scheme

E-Pirate, a high-profile RCMP investigation, alleged the involvement of Silver International Investments, its directors, Caixuan Qin, and Jain Jun Zhu, and their associate, Paul King Jin, into transnational money laundering, underground banking, narcotics importation, and trafficking, evading taxes and using drug money to fund VIP gamblers in B.C. casinos. According to documents obtained by Postmedia News, Jin's operation allowed ultra-wealthy Chinese businesspeople, few with ties to organized crime, to transfer wealth from China to Canada while evading China's tight capital export controls. [30]He allegedly helped "whale" Mainland China gamblers in Macau to buy chips and gamble in B.C. namely at, Richmond's River Rock, Burnaby's Grand Villa, and New Westminster's Starlight Casino, in addition to illegal gaming houses set up in rural Richmond. Initially identified in 2012, the anti-money-laundering investigators and B.C. law enforcement identified Jin's network of 'private lenders' who assisted Chinese tycoons in developing real estate within the province. [31]Suspected of logging 50 LTC's and $1.24 million in cash buy-ins from 2012 to 2014, he was banned from all B.C. casinos for five years, given his extensive history of suspicious incidents. Jin, a target of two money-laundering investigations in the last five years, was arrested in E-Nationalize, another inquiry into money laundering carried out by Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit and B.C. Prosecution Services. [32]In September 2020, a Richmond restaurant shooting killed Zhu; meanwhile, Jin was shot and wounded.

Popularly regarded as the most massive money laundering probe in Canadian history and a crucial prosecution for B.C., E-Pirate held a chilling effect on gamblers, to the extent that casinos in the province became ghost towns. Nonetheless, the investigation collapsed in November 2018, owing to an evidence disclosure procedural lapse wherein federal prosecutors mistakenly revealed the identity of a secret police informant [33]as they released a large volume of digital files to Silver's lawyers. Adjudged to be at 'high risk' for death, prosecutors and the RCMP followed legal guidelines, thereby deciding the informant's life outweighed the criminal proceedings. Regardless of the department's efforts to quietly stay the charges against Silver and its operators, Kim Bolan from theVancouver Sun probed the matter. She discovered several organizational cracks were present in the investigation apart from the inadvertent disclosure of unvetted documents. These included a new leader's appointment to the unit who prompted officers to instead focus on trade-based money-laundering investigations – dirty money used to purchase legitimate commerce goods. Nearly 32 cops working on the Silver International file from spring 2015 until the fall of 2017 were reassigned, despite the trial's onerous demands.

Conclusion

Watchdog Flaws: Problematic Framing

As a civilian watchdog, the Vancouver media extensively followed the trail of dirty money flowing through local casinos and the provincial government's dereliction in its retrenchment. However, in their coverage, journalists seldom emphasized the macroscale implications of money-laundering extending far beyond the sky-rocketing real estate prices of Lower Mainland. According to a 2019 Criminal Intelligence Service report on organized crime in Canada, the most common ways to launder money was through private businesses such as restaurants and bars, automotive and construction firms, as well as clandestine money services. Casino and gambling came third, meanwhile money-laundering through real-estate though widely reported, only accounted for seven percent.[34][35]

Money laundering across British Columbia has had sweeping impacts ranging from state manifested corruption and the opioid crisis to immigration frauds. Vancouver's housing prices have certainly escalated over the years, owing to the provinces' archetypal location, demand-supply variants, and increasing soft costs (insurance, homeowner protection, regular appraisal, development costs, municipal fees, property taxes). Yet, in its coverage of the 'Casino Coup,' media has thoroughly been fixated on real-estate as the singular sector affected by dirty money flowing through the province.

A large chunk of this cash flows through methamphetamine networks imported via Chinese and Mexican cartels, thereby worsening Canada's opioid crisis. As per the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, presently, Canada is living through an opioid epidemic wherein nearly 11,500 opioid-related deaths have happened between January 2016 and December 2018. However, the local media's disregard of the urban drug culture permeating the Downtown east side and their general apathy towards the opioid crisis and its catalysis due to money laundering has diametrically impacted their reporting of the casinos.

The outlets have further indulged in a race-tinted coverage by centralizing their reporting primarily around the illicit transfer of money through Chinese triads, whereas in actuality, the Vancouver Model's key players also include Mexican cartels, North Korean networks, and Iranian organized crime groups. Perhaps, as Erving Goffman argues in 'Frame Analysis' (1974), the freedom of expression and speech enjoyed by media outlets is a double-edged sword. Therefore, the media frequently catapults the audience by telling them what to think (agenda-setting theory) and guiding them on how to think about the issue (framing theory).

Reference

List of the references here.

- ↑ German, Peter. (2019). Dirty Money - Part 2. Turning the Tide - An Independent Review of Money Laundering in B.C. Real Estate, Luxury Vehicle Sales & Horse Racing. 12. https://icclr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Dirty_Money_Report_Part_2.pdf?x61621

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 German, R. M. (2018). Dirty Money: An Independent Review of Money Laundering in Lower Mainland Casinos conducted for the Attorney General of British Columbia. https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/Gaming_Final_Report.pdf

- ↑ Lindsay, Bethany (May 26, 2020). "Vancouver model for money laundering unprecedented in Canada, B.C. inquiry hears". CBC. Retrieved 29 November, 2020. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Hunter, Justine (May 9, 2019). "Dirty money driving up B.C. home prices as more than $40-billion laundered across Canada in 2018". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of May 26, 2020, 20.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 3, 2020, 10. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%203,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Statutes of British Columbia. (2002). Gaming Control Act, Section 7.1. https://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/02014_01#part2.

- ↑ Statutes of British Columbia. (2002). Gaming Control Act, Section 8. https://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/02014_01#part2.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 12, 2020, 57. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%2012,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ German, Peter. (2018). Dirty Money: An Independent Review of Money Laundering in Lower Mainland Casinos Conducted for the Attorney General of British Columbia, 66. https://cullencommission.ca/other-reports/.

- ↑ German, Peter. (2018). Dirty Money: An Independent Review of Money Laundering in Lower Mainland Casinos Conducted for the Attorney General of British Columbia, pp. 58 & 67. https://cullencommission.ca/other-reports/.

- ↑ Seelig, J., & Seelig, M. (1998). “Place Your Bets!” On Gambling, Government and Society. Canadian Public Policy 24 (1), 92.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 12, 2020, 223. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%2012,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Statutes of British Columbia. (2002). Gaming Control Act, Section 23. https://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/02014_01#part2.

- ↑ German, Peter. (2018). Dirty Money: An Independent Review of Money Laundering in Lower Mainland Casinos Conducted for the Attorney General of British Columbia, 75. https://cullencommission.ca/other-reports/.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 3, 2020, 7. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%203,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 12, 2020, 56. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%2012,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 3, 2020, 6. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%203,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 3, 2020, 19. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%203,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 12, 2020, 57. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%2012,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 12, 2020, 114. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%2012,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Cullen Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. (2020). Proceedings at Hearing of November 3, 2020, 21. https://cullencommission.ca/data/transcripts/Transcript%20November%203,%202020.pdf.

- ↑ Reynolds, Harry W. Ethics in American Public Service. Sage Periodicals Press, 1995.

- ↑ Chiang, Chuck (June 27, 2018). "Report dissects 'Vancouver Model' of money laundering". BIV - Business Intelligence For B.C.

- ↑ Mason, Gary (June 29, 2018). "Is British Columbia the corruption capital of Canada?". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Pearson, Natalie Obiko (May 10, 2019). "How Vancouver became the world's laundromat for foreign organized crime?". Financial Post.

- ↑ "B.C. Casinos to Shift Away from Cash Transactions". CBC News. August 24, 2011.

- ↑ "B.C. casinos rapped for not checking patrons' background". CBC News. February 22, 2012.

- ↑ "River Rock, Starlight casinos saw $27M in suspicious transactions this spring". CBC News. October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Lindsay, Bethany (May 26, 2020). "Vancouver model for money laundering unprecedented in Canada, B.C. inquiry hears". CBC News.

- ↑ Cooper, Sam (April 29, 2018). "How Chinese gangs are laundering drug money through Vancouver real estate". Global News.

- ↑ Hoekstra, Gordon (November 06, 2020). "Alleged B.C. money launderer Paul King Jin gets standing at Cullen inquiry". Vancouver Sun. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Cooper, Sam (January 9, 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: Crown mistakenly exposed police informant, killing massive B.C. money laundering probe". Global News.

- ↑ Acoulon, Sandrine Gagné (March 06, 2020). "Canada: Real-Estate Firms Violate Anti-Money Laundering Rules". OCCRP - Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Acoulon, Sandrine Gagné (June 15, 2020). "Province of British Columbia is Canada's Crime, Money Laundering Hub". OCCRP - Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.