Course:PostgradFamilyPractice/ExamPrep/99 Priority Topics/Low Back Pain

Low-back Pain - Key Features

1. In a patient with undefined acute low-back pain (LBP):

a) Rule out serious causes (e.g., cauda equina syndrome, pyelonephritis, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, cancer) through appropriate history and physical examination.

b) Make a positive diagnosis of musculoskeletal pain (not a diagnosis of exclusion) through an appropriate history and physical examination.

2. In a patient with confirmed mechanical low back pain:

a) Do not over-investigate in the acute phase.

b) Advise the patient:

- that symptoms can evolve, and ensure adequate follow-up care.

- that the prognosis is positive (i.e., the overwhelming majority of cases will get better).

3. In a patient with mechanical low back pain, whether it is acute or chronic, give appropriate analgesia and titrate it to the patient’s pain.

4. Advise the patient with mechanical low back pain to return if new or progressive neurologic symptoms develop.

5. In all patients with mechanical low back pain, discuss exercises and posture strategies to prevent recurrences.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Low Back Pain

Table 1 –

| Disease/Condition | Patient age (years) | Location of pain | Quality of pain | Aggravating or relieving factors | Signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back strain | 20 to 40 | Low back, buttock, posterior thigh | Ache, spasm | Increased with activity or bending | Local tenderness, limited spinal motion |

| Acute disc herniation | 30 to 50 | Low back to lower leg | Sharp, shooting or burning pain, paresthesia in leg | Decreased with standing; increased with bending or sitting | Positive straight leg raise test, weakness, asymmetric reflexes |

| Osteoarthritis or spinal stenosis | >50 | Low back to lower leg; often bilateral | Ache, shooting pain, “pins & needles” sensation | Increased with walking, especially up an incline; decreased with sitting | Mild decrease in extension of spine; may have weakness or asymmetric reflexes |

| Spondylolisthesis | Any age | Back, posterior thigh | Ache | Increased with activity or bending | Exaggeration of the lumbar curve, palpable “step off” (defect between spinous processes), tight hamstrings |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | 15 to 40 | Sacroiliac joints, lumbar spine | Ache | Morning stiffness | Decreased back motion, tenderness over sacroiliac joints |

| Infection | Any age | Lumbar spine, sacrum | Sharp pain, ache | Varies | Fever, percussive tenderness; may have neurologic abnormalities or decreased motion |

| Malignancy | >50 | Affected bone(s) | Dull ache, throbbing pain, slowly progressive | Increased with recumbency or cough | May have localized tenderness, neurologic signs or fever |

| Other diagnoses to consider: • Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): Sudden; severe; constant back/flank/abdominal/groin pain, syncope, hypotension, shock (cyanosis, ↓ LOC, ↑HR, ). Past hx of: peripheral vascular disease, smoking, COPD, HTN. FamHx of AAA. Pulsatile abdominal mass (<50% of cases). Abdominal bruit. | |||||

History

1) Characterize the pain (OPQRST)

2) Ask about Red Flags to identify potentially serious problems requiring immediate diagnostic testing.

mnemonic BACK PAIN

B – Bowel/bladder dysfunction

A – Anaesthesia (Saddle)

C – Constitutional symptoms (wt loss, fevers, chills, nt sweats, ↓energy)

K – Chronic disease, including history of malignancy, osteroporosis,

P – Parasthesias

A – Age > 50

I – IV drug use, Immunosuppression (e.g. corticosteroid use)

N – Neuro deficit, night-time pain or pain worse/unrelieved when lying down

Patients that should be seen on an urgent basis are the following:

a) Those with features of Cauda Equina Syndrome: loss of bladder/bowel control, widespread progressive neurological symptoms or signs in lower limbs (leg weakness or gait abnormalities), saddle area anesthesia or lax anal sphincter

b) Fever (38 C or 100.4 F that persists longer than 48 hours)

c) Severe unrelenting pain at rest or at night

3) Ask about Yellow Flags to identify potential barriers to resuming or increasing activity (i.e. risk factors for chronicity).

a) Fear of movement/ re-injury → avoidance behaviour

b) Pain catastrophizing (misinterpreting any pain as a sign of underlying catastrophic cause)

c) Pain beliefs (including increased bodily awareness and pain “hypervigilence”)

d) Depression

Patients with yellow flags require constant reassurance and counseling by their family physician, especially within 4-6 weeks of onset, before the back pain becomes chronic.

4) Consider the following Risk Factors for developing back pain: Smoking, obesity, age, female gender, strenuous work / sedentary work / psychologically strenuous, low education, job dissatisfaction and psychiatric problems.

Physical Examination

• Inspection – posture, gait, scoliosis, kyphosis, pain behaviour

• Back examination

- o Palpation – Tenderness of bone / soft tissue

- o ROM and painful arc

- o Mobility (test by having patient, sit, lie down and stand up)

• Neurological exam

- o Sensory:

- L3 – Medial knee

- L4 – Medial ankle

- L5 – Middle foot / web space big toe

- S1 – Lateral foot / posterior calf

- o Motor:

- L3 – Extend knee

- L4 – dorsiflex ankle

- L5 – extend big toe

- S1 – plantar flex ankle

- o Reflexes

- L4 – Knee jerk

- S1 – Ankle jerk

• Straight leg raise – For radiculopathy (impingement of nerve root)

- o Positive if Sciatica reproduced b/w 10-60 deg

• Crossed straight leg – lift other leg and pain is reproduced in affected leg

• Seated straight leg – seated position, extend leg to 90 deg → pain

• Pedal pulses

• +/- Hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, DRE

Waddell’s Signs – Non-organic signs indicating the presence of a functional component of back pain.

• Superficial, non-anatomic tenderness

• Pain with simulated testing (e.g. axial loading or pelvic rotation)

• Inconsistent response with distraction (e.g. straight leg raises while the patient is sitting)

• Nonorganic regional disturbances (e.g. non-dermatomal sensory loss)

• Overreaction

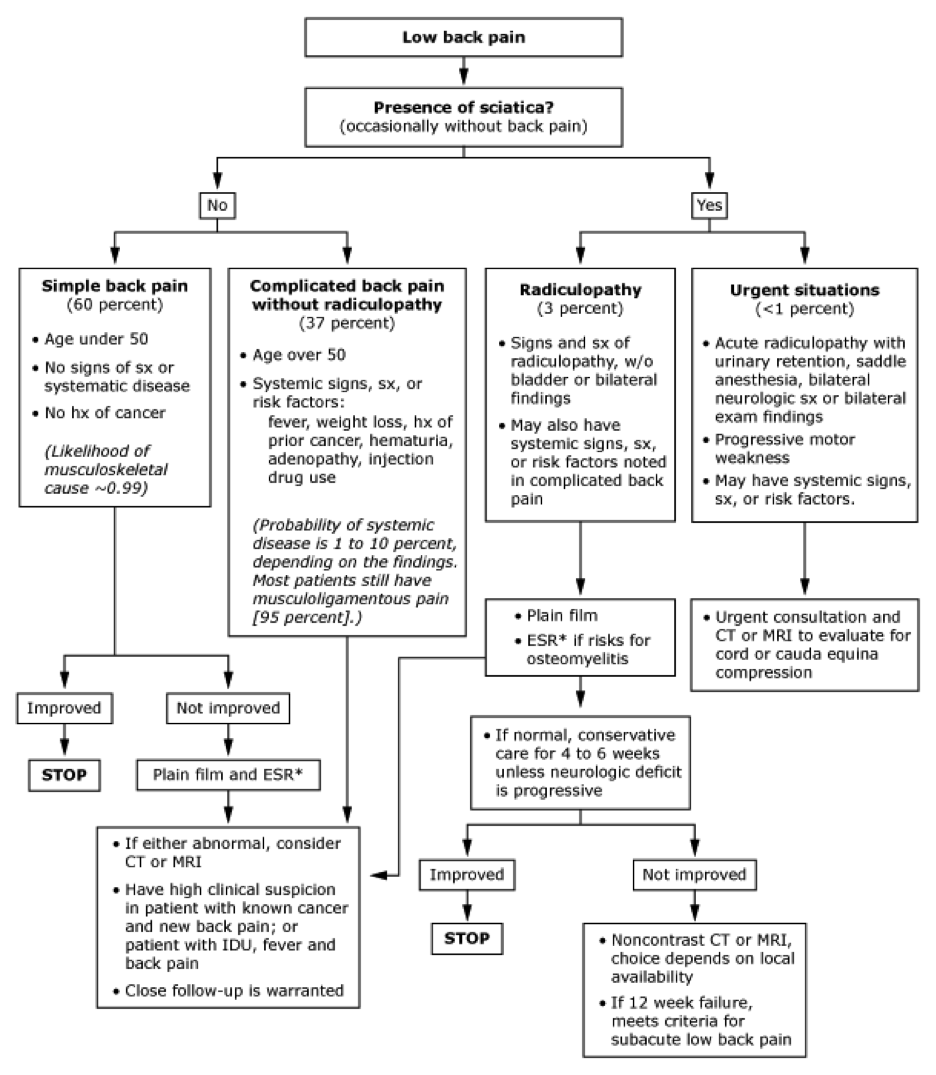

Investigations

• CBC, ESR/CRP, PSA, alkaline phosphatase, calcium, particularly to evaluate for infection and malignancy

• Imaging is usually unnecessary in first 4-6 weeks as demonstrated by two large retrospective studies, unless one of the following indications is present.

• Indications for radiographs in patients with acute low back pain:

- o History of significant trauma

- o Neurologic deficits

- o Systemic symptoms

- o Temperature greater than 38°C (100.4°F)

- o Unexplained weight loss

- o Medical history of cancer, corticosteroid use, drug or alcohol abuse

- o Ankylosing spondylitis suspected

• If there is minimal improvement in pain and function by 4-6 weeks, consider spine x-ray. CT scan or MRI imaging may be subsequently necessary, however, they have been found to demonstrate abnormalities in “normal” asymptomatic” people which may not correlate with clinical symptoms.

• Consider bone scan if normal radiographs but high suspicion of osteomyelitis, bony neoplasm or occult fracture.

• Consider needle electromyography and nerve conduction studies to differentiate peripheral neuropathy from radiculopathy and myopathy.

Management

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC

- 1) Activity

- a. Exercise – Aerobic activity (e.g. walking, biking, swimming) that minimally stress the back, with gradual increase in daily recommended levels. Core muscle strengthening exercises (e.g. oblique abdominal and spinal extensor muscles) should be included in the physical therapy exercise regimen.

- b. Activity restriction to avoid the painful arcs of motion. Caution with activities such as long distance driving, heavy lifting, sitting for prolonged periods, repetitive twisting and reaching.

- c. The current recommendation is 2 to 3 days of bedrest in the supine position for patients with acute radiculopathy, as sitting increases intradiscal pressures and can worsen herniation and pain. Bedrest has not been shown to be beneficial and may be harmful in other causes of back pain.

- 2) Physical therapy modalities – Superficial heat or cold packs, massage therapy and ultrasound (deep heat) are useful for symptom relief in the acute phase and there use should be limited to the first 2-4 weeks after the injury.

- 3) No convincing evidence has been demonstrated for lumbar traction, transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) or corsets.

PHARMACOLOGIC

- 1) Analgesics in the acute phase should be used on a time-contingent basis (e.g. QID) rather than a pain-contingent basis.

- a. NSAIDS are the mainstay of treatment. A 2-4 week course is recommended. If there is a history of peptic ulcer disease, H2-antagonist or Misoprostol should be prescribed for gastrointestinal prophylaxis.

- • Ibuprofen 600 mg QID, or

- • Naproxen 500 mg BID, or

- • Diclofenac 50mg BID

- b. Acetaminophen and/or Acetaminophen with codeine can be added as an adjuvant (<4000mg per day).

- c. Muscle relaxants (Cyclobenzaprine, Methocarbamol, Baclofen) are no more effective than NSAIDS.

- d. Short-term course of narcotics can be used in the acute phase, if necessary.

- • Tramadol 50-100 mg QID

- • Tylenol #3 1-2 tabs q4h PRN

- • Dilaudid (hydromorphone) 2-4mg q4h PRN

- • Oxycodone (Oxycontin) 2.5-5 mg q6h PRN

- • Oxymorphone – 5-10 mg q6h PRN

- • Morphine

- e. Chronic pain, consider Gabapentin or Pregabalin

- f. Corticosteroid injections

- a. NSAIDS are the mainstay of treatment. A 2-4 week course is recommended. If there is a history of peptic ulcer disease, H2-antagonist or Misoprostol should be prescribed for gastrointestinal prophylaxis.

SURGICAL

- Indications for immediate surgical consultation – suspected cauda equine lesion, worsening neurological deficits or intractable pain resistant to conservative treatment.

FOLLOW-UP

- 1) In 2 weeks if the patient is not finding any improvement.

- 2) At follow-up visit, update history and physical exam. Reassess for red flags and neurological deficits.

Study Guide

Resources

American Family Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Back Pain. 2000. www.aafp.org/afp/2000/0315/p1779.html

McMaster Module. Back Pain. 2004.

Toward Optimized Practice Program. Guideline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain. 2011. www.topalbertadoctors.org/cpgs.php?sid=63&cpg_cats=85

Toward Optimized Practice Program Low Back Pain Guideline Summary