Course:PHYS350/Small Oscillations and Perturbed Motion

In Linear Motion, we argued that all sufficiently small oscillations are harmonic. In this section we will exploit this result in several ways to understand

- The motion of systems with many degrees of freedom near equilibrium,

- The motion of systems perturbed from known solutions, and

- The motion of systems with Lagrangians perturbed from systems with known solutions.

All three of these points are applications of perturbation theory, and they all start with the harmonic oscillator.

Normal Modes

The modes of oscillation of systems near equilibrium are called the normal modes of the system. Understanding the frequencies of the normal modes of the system is crucial to design a system that can move (even it isn't meant to). Let's look at a system with many degrees of freedom; we have

Let be an equilibrium position and expand about this point so .

We can expand the potential energy to give

The first term is a constant with respect to and constant terms do not affect the motion. The second term is zero, because is a point of equilibrium so we are left with

where

and

yielding the equations of motion

This is a linear differential equation with constant coefficients. We can try the solution

so we have

This is a matrix equation such that

with

and

This equation only has a solution is . This gives a th-degree polynomial to solve for . We will get solutions for that we can substitute into the matrix equation and solve for .

Is this guaranteed to work? Yes, it turns out. Look at the equation in terms of matrices we have

The matrix is symmetric and real. The matrix should be positive definite (because a negative kinetic energy doesn't make sense). Technical issue: If has a null space, the degrees of freedom corresponding to the null space are massless and cannot be excited unless they are in the null space of . Either way, you can drop the null space from both sides of the equation.

Assuming that is invertable we have

and we have a standard eigenvalue equation. In most examples, the kinetic energy matrix will be diagonal, so it is straightforward to construct the quotient matrix and diagonize it.

Perturbations about Steady Motion

Let's say I have some solution to the equations of motion and I would like to look at small deviations from the solution. Let's satisfy

and let's look at

where is small. Let's expand the entire Lagrangian to find the equations of motion for the deviations . We have

Now let's apply Lagrange's equations for the deviations

to give

The two terms without actually cancel each other out, leaving the following equations of motion.

In steady motion, the partial derivatives are taken to be constant in time yielding the even simpler result

Again we have a linear differential equation with constant coefficients, and all of the results from the previous section carry over.

Perturbed Lagrangians

What about finding solutions to Lagrangians that are almost like ones that we have already solved? Let's say we have

where is considered to be small compared to Let's say I have some solution to the equations of motion for and I would like to look at small deviations from the solution induced by the change in the Lagrangian. Let's say satisfy

and let's look at

where is small. Let's expand the entire Lagrangian to find the equations of motion for the deviations . We have

Now let's apply Lagrange's equations for the deviations

to give

The two lowest orders terms without actually cancel each other out, leaving the following equations of motion.

Let's specialize and assume that the unperturbed motion is steady so the partial derivatives of the unperturbed Lagrangian are constant in time, to obtain

which is the equation of a coupled set of driven harmonic oscillators.

Examples

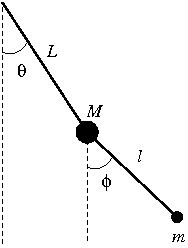

Double Pendulum

The kinetic energy is

If we take the small angle approximation we have

so we can define the orthogonal coordinates,

and

Let's write out the potential energy,

and in the small angle approximation

Let's now write out the equations of motion

We can write this as a matrix equation,

Now let's substitute the solution to get

We have the characteristic equation

or

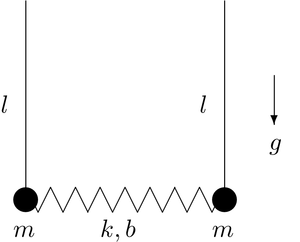

Coupled Pendulums

Let's use the horizontal displacements of the two pendulum bobs as our coordinates ( and ). When the bobs are vertical they are an equilibrium distance apart. The vertical position of the bobs are

and .

The distance between the bobs is

We can write the potential energy as

Let's write the kinetic energy, we have

Let's write out the equations of motion,

where and . Let's substitute and write the result as a matrix equation,

If we have . If we have .

Central Force

Let's try to find the equations for small perturbations to a central force whose potential is a power-law of radius. We have the following Lagrangian,

Let's find the steady solution first (). we have

so

For the θ-equation we have

so is constant if the radius is constant.

Let's take

and substitute into the Lagrangian,

According to the rules of perturbation theory, we can drop all the terms that are constant and linear in and keep the second order terms to get

Now let's get the equations of motion, we have

and

so

which we can substitute into the equation for to get

so

Anharmonic Oscillator

The final type of problem that one can treat in perturbation theory is a perturbation to the Lagrangian itself. As an example we shall do the aharmonic oscillator

which yields the equation of motion

Let's look for a solution as a series of approximations

and

where there are corrections to both the function dependence of the motion and the frequency of the oscillations. Let's rewrite the equation of motion a bit

The way that we solve such a differential equation is to substitute the trial solution into it and group the terms according to the sum of their superscripts and consider each bunch of terms a separate equation to solve. Let's look at the first order terms:

First-order terms

All of the terms on the right-hand side have superscripts that add to more than one. This equation is satisfied identically.

Second-order terms

This is the equation for a driven harmonic oscillator. The final term drives the oscillator at its natural frequency (). This would cause the perturbation to grow without bound which doesn't make sense; it violates perturbation theory but we have the freedom to make the final term go away by taking

so the frequency is unchanged at this order. To solve for the terms that remain, we take the particular solution to the differential equation. The solution to homogenous looks just like , so it is already included. We have

Third-order terms

We can write all of the terms on the right-hand side as a sum of a constant, a term proportional to and to give

As before we would like for the final term to vanish so we take

and we solve for as before to give

If we combine these results we see that we can use how the period of the oscillation changes with amplitude or the relative size of the various harmonics to determine the anharmonic terms in the Lagrangian.