Course:PHYS341/Archive/2016wTerm2/FormantandTimbreintheHumanVoice

Formant and Timbre in the Human Voice

Timbre is the term used to describe the perceived sound quality of a voice. The Timbre of the human voice is affected largely by the formants in the vocal tract. These formants are aspects of the vocal tract that resonate more strongly at certain frequencies. They are labeled "formants" because their resonance is very broad, due to the soft walls of the vocal tract. Because these formants resonate more strongly at certain frequencies, these frequencies will have a larger amplitude, thus, these frequencies will sound louder. When the initial sound created through vibrating vocal folds passes the vocal tract, the partial frequencies of the sound that are closer in frequency to the formants will be louder.[1]. Because each human has natural formants with different resonances, each voice has different sound characteristics. Because of this, each voice has its own unique sound, and it is this effect that is known as timbre.

Affecting timbre

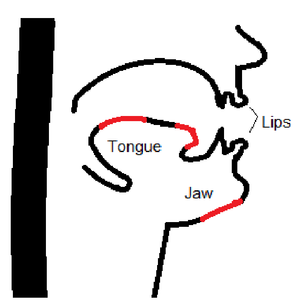

Because the formants of the voice rest in the soft walls of the vocal tract, they can be affected by adjusting the shape of the vocal tract. Adjusting the vocal tract can thus lower or raise the frequencies at which the formants resonate, thereby changing the quality of sound emitted. While there are many ways to adjust the vocal tract, there are three main ways to affect the formants: the jaw, the body of the tongue, and the tip of the tongue [1]. (fig.1.)

Vowels

The frequency at which these formants resonate is what affects the sound of the vowels produced. This is why the jaw and tongue are required to adjust vowel sounds, as they change the shape of the vocal tract, which alters the formants within. This causes the formats to resonate at different frequencies, resulting in the desired vowel sound. For example, one must have an open mouth, with the tongue on the base of the mouth in order to produce the "ah" sound in "father" (fig.2). This sound cannot be made if the jaw is closed, or if the tongue is on the roof of the mouth.

Vowel quality

Much like vowels themselves, vowel quality is also a result of formants. Vowel quality itself is an important part of timbre, and defines the way in which one perceives a vowel. popular nomenclature includes two very common descriptions of a vowel: "dark" vowels, and "bright" vowels. Dark vowels tend to have a more aspirated quality, and when sung often feel very far back in the mouth. They are created when a vowel is given more space than normal, by lowering the jaw and the body of the tongue. Bright vowels are the opposite, they have a very pointed and definite sound quality, and when sung often feel very far forward in the mouth. They are created when a vowel is given less space than normal, by raising the jaw and the body of the tongue. See fig.3 for a sonogram of the difference between normal, dark, and bright vowels. From a musical perspective, dark vowels have a tendency to be under the desired pitch, technically known as a few cents flat. Conversely, bright vowels have a tendency to rise above the desired pitch, technically known as a few cents sharp. Because of this, singers who want a darker or brighter quality to their timbre often have to practice singing the desired quality of vowel in order to stay on the desired pitch. While timbre encompasses the entire field of psychoacoustic sound interpretation, it is often used in singing to talk specifically about vowel quality.

Styles of singing

Because of the many different ways of manipulating vowel quality, different styles of singing the same notes and lyrics emerge. The barbershop style of music is intended to be sung with a very bright tone. Conversely, choral music tends to avoid both dark and bright vowels, favoring a sound somewhere in the middle.

Ensemble singing

Because different disciplines of singing often foster different timbres, it can be difficult for one to sing in a cross discipline ensemble. If multiple singers attempt to sing together (either in unison or harmony), but they do not match in timbre, they will not sound as pleasing as singers that do. When this happens, it is usually very easy to identify each individual singers voice, as they have a distinct difference in formants, and thus our ears can pick out each sound's source more easily. A cross discipline singer will often have to learn how to manipulate their formants in several different ways, in order to appropriately match their vowel quality to the singers around them. This is one of the reasons why vowel quality and timbre are very important when making a sound as an ensemble.