Course:MEDG550/Student Activities/Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT)

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT)

Overview

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a heart condition where people faint when they are emotionally stressed or exercising.[1] The human heart typically beats about once every second and follows a steady beating pattern to move blood around the body. The heart has an electrical system that allows the heart to pump blood in a steady beating pattern.[2] When people with CPVT exercise or experience stressful emotions, the electrical system stops working properly, and their heartbeat speeds up and no longer follows a regular beating pattern.[3] This fast, irregular heartbeat can result in people fainting and, if it continues, can result in a person’s heartbeat stopping if they do not get medical help.[1][2]

Features

The main symptom of CPVT is fainting when experiencing stressful emotions or exercising. When a person with CPVT starts having a fast, irregular heartbeats, which is caused by stressful emotions or exercise, it can lead to symptoms including:[4]

- Fainting

- Heartbeat suddenly stopping (cardiac arrest)

- Sudden death

- Minor symptoms: dizziness and heart feeling like it is beating quickly or hard (palpitations)

About 1/10,000 people (0.0001%) have CPVT. Both females and males can have CPVT. Females, on average, start showing symptoms around 20 years old. Males start to show symptoms earlier during childhood or in their teens. In rare situations, someone might experience their first symptom of CPVT in their 30s or 40s.[4] The majority of people with CPVT, who have a spelling mistake in a gene that causes their CPVT, will experience symptoms. [1]

Diagnosis

If someone is thought to have CPVT, they will have testing completed to figure out if they have the condition. The tests include:[5]

- Echocardiogram - this is a special ultrasound of the heart

- EKG - this looks at the rhythm of a person’s heartbeat while resting (i.e. not exercising)

- Exercise Stress Test - this looks at the rhythm of a person’s heartbeat when they are exercising (see Photo 1)

People with CPVT do not have a heart with structural differences (ex. holes in their heart) and have a typical heartbeat rhythm when resting. However, when exercising or experiencing stressful emotions, people with CPVT have a heartbeat that is fast and irregular.[5]

People who have CPVT can also have genetic testing to see if they have a spelling mistake in one of their genes that causes the gene to not work properly, and causes their CPVT.[1][6] Note: the section titled “Genetics” discusses more about genes not working properly and what genes are involved in CPVT.

Management and Treatment

Management and treatment approaches are available for CPVT.[5] Below is a summary of the different treatments/recommendations for CPVT. Please discuss all treatment and management options/changes with your doctors.

- Medications - certain medications can help prevent the heartbeat from beating quickly and irregularly due to exercise or stressful emotions[6][1]

- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) - a machine that is placed in the chest of some people who have CPVT (depending on their symptoms) to restart their heart if it stops beating[6][5]

- Lifestyle change recommendations - it is recommended to avoid tiring exercise, stressful environments, dehydration and competitive sports[5]

- Note: some of these recommendations may change depending on how well medication controls the heartbeat speed/rhythm in a person with CPVT[6]

- Pregnancy-specific management - pregnancy does not increase someone’s chance of experiencing symptoms related to CPVT[7]

- If a person who has CPVT is pregnant, it is recommended that they are followed by doctors who are very familiar with the heart condition and pregnancy. These healthcare providers will be able to provide the best medical recommendations.[7]

It is important that people with CPVT are monitored by their doctors, even after starting treatment, to ensure that the selected treatment continues to be the best option for them.

Genetics

As humans, we all have genetic information. This genetic information is called DNA. DNA is like an instruction book for our body - it tells us how to develop and become the humans that we are. Our genes are like the sentences in an instruction book; they are smaller portions of our genetic information, are made up of letters, and give our body instructions. Typically, humans have two copies of each gene. We receive one copy from our biological mother and one from our biological father.When there is a spelling mistake in a sentence, it causes the sentence and the instructions that it provides to no longer make sense. This is the same as genes. A spelling mistake in a gene causes the gene not to work properly, and the person develops symptoms.

CPVT is a genetic disease. In people with CPVT, RYR2 and CASQ2 are the most common genes that do not work properly (see Table 1).[1] RYR2 and CASQ2 help control levels of a molecule (calcium) in our heart cells.[3] Calcium is a part of the heart's electrical system.[7] When either of these genes do not work properly, the body is not as good at controlling how much calcium enters heart cells. Exercising or experiencing emotional stress contributes to calcium entering the heart cells. Because too much calcium enters the cells (as a result of RYR2 or CASQ2 are not working properly and not being as good at controlling calcium levels), the heart starts to beat quickly and irregularly.[3] This can lead to the person fainting or suddenly dying.[1]

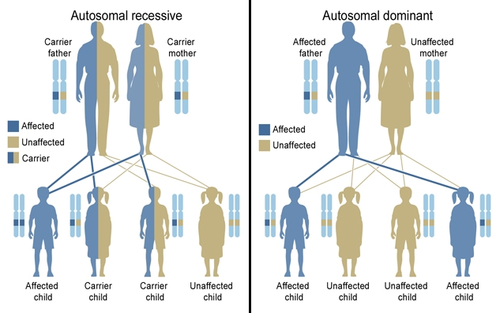

Depending on which gene has the spelling mistake, a person will have CPVT if one copy of a gene is not working properly (this is called autosomal dominant), or if both copies of a gene are not working properly (this is called autosomal recessive) (see Table 1; see Photo 2). Note: Also, about 1/4 (25%) of individuals with CPVT do not have a known spelling mistake in a gene listed above that explains their symptoms of CPVT.[5]

| Gene | Inheritance Pattern | Percentage of Individuals with CPVT with Spelling Mistakes in these Genes |

|---|---|---|

| RYR2 | AD | 60-70% |

| CASQ2 | AR (rarely AD) | 2-5% |

| KCNJ2 | AD | <1% |

| CALM1 | AD | <1% |

| CALM2 | AD | <1% |

| CALM3 | AD | <1% |

| TRDN | AR | <1% |

| TECRL | AR | <1% |

Table 1. This table shows which genes (when spelling mistakes exist) cause CPVT, whether they are autosomal dominant or recessive, and the percentage of people with CPVT with spelling mistakes in each gene.[4][1]

Autosomal Dominant Inheritance

If a person has one copy of RYR2, KCNJ2, CALM1, CALM2, CALM3 and rarely CASQ2 that is not working properly, they have CPVT.[4][1]

For example, someone with one non-working copy of RYR2 has a 1/2 (50%) chance of passing down their non-working copy of RYR2 to their child. This child would have CPVT. The same person also has a 1/2 (50%) chance of passing down their working copy of RYR2 to their child. This child would not have CPVT (see Photo 2).[1]

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

If a person has two copies of CASQ2, TRDN or TECRL that do not work properly, they have CPVT.[4][1]

If someone has one copy of CASQ2 that works properly and one that does not, they are called a “carrier”. Carriers do not have CPVT. If two people are carriers who plan to have a child, they have a:

- 1/4 (25%) chance of having a child with two non-working copies of the gene

- 1/2 (50%) chance of having a child who has one non-working copy of the gene (they would be a “carrier”)

- 1/4 (25%) chance of having a child with two working copies of the gene

Therefore, they have a 1/4 (25%) chance of having a child with CPVT and 3/4 (75%) chance of having a child who does not have CPVT (see Photo 2).[1]

About 3-4/10 (30-40%) of people with CPVT will be the first person in their family with a spelling mistake in a gene that causes CPVT - they won’t have received the spelling mistake from a parent.[1] Instead, the spelling mistake occurred randomly within them during the very early stages of pregnancy.[8]

Genetic Counselling for CPVT

Genetic counsellors are healthcare workers who have received training in counselling and genetics. Genetic counsellors support individuals and families with genetic conditions or those who are suspected of having genetic conditions. Genetic counsellors help people understand more about their genetic condition, provide emotional support and help with decision-making.[9]

Genetic counsellors may help people with CPVT:

- Better understand the genetics of CPVT

- Organize genetic testing to confirm if the person has a gene (or two) that is not working properly that causes their CPVT

- Process their diagnosis and changes to their life and/or provide emotional support to the family of a child who has been diagnosed

If a person is found to have a non-working copy of a gene (ex., RYR2) that causes their CPVT, it is recommended that other family members (ex., their parents, siblings and children) have genetic testing to see if they also have the same non-working copy of the gene.[4] Family members can be referred to a genetics clinic to speak with genetic counsellors and organize genetic testing. Children can have genetic testing for CPVT as a positive genetic test result (ex., a copy of RYR2 has a spelling mistake) as things can be done in childhood to minimize the chances of having CPVT symptoms.[10][5][11]

If a person has a non-working copy of a gene that causes CPVT (ex. RYR2) and wants to have a child, they can talk to a genetic counsellor about their chances of having a child with CPVT and their options for testing during a pregnancy.[1]

Patient Resources

CPVT is a rare condition, and people diagnosed with CPVT may or may not have family members diagnosed with the condition.[1][12] The resources below are provided if you would like to learn more about the condition and connect with others with CPVT.

https://sads.org/sads-conditions/cpvt/

- This resource provides fact sheets and brochures about CPVT, links to sign up for a virtual support group for individuals with arrhythmia-related conditions, and a blog with people’s stories about living with arrhythmia-related conditions (including CPVT).

- The resource provides a summary about CPVT. At the bottom of the website there is a list of helpful things to think about before and during a meeting with a doctor to talk about CPVT.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Napolitano, Carlo, Andrea Mazzanti, Raffaella Bloise, and Silvia G. Priori. “Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia.” In GeneReviews®, edited by Margaret P. Adam, Jerry Feldman, Ghayda M. Mirzaa, Roberta A. Pagon, Stephanie E. Wallace, and Anne Amemiya. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1289/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rappel, Wouter-Jan. “The Physics of Heart Rhythm Disorders.” Physics Reports, The physics of heart rhythm disorders, 978 (September 19, 2022): 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2022.06.003.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Priori, S. G., Mazzanti, A., Santiago, D. J., Kukavica, D., Trancuccio, A., & Kovacic, J. C. (2021). Precision medicine in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: JACC focus seminar 5/5. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 77(20), 2592-2612. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.073

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Aggarwal, Abhinav, Anton Stolear, Md Mashiul Alam, Swarnima Vardhan, Maxim Dulgher, Sun-Joo Jang, and Stuart W. Zarich. “Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Evaluation and Therapeutic Strategies.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 6 (January 2024): 1781. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061781.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Priori, Silvia G, Carina Blomström-Lundqvist, Andrea Mazzanti, Nico Blom, Martin Borggrefe, John Camm, Perry Mark Elliott, et al. “2015 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC).” European Heart Journal 36, no. 41 (November 1, 2015): 2793–2867. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Abbas, M., Miles, C., & Behr, E. (2022). Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review, 11. DOI: 10.15420/aer.2022.09

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Landstrom, A. P., Dobrev, D., & Wehrens, X. H. (2017). Calcium signaling and cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation research, 120(12), 1969-1993. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310083

- ↑ Definition of de novo mutation—NCI Dictionary of Genetics Terms—NCI (nciglobal,ncienterprise). (2012, July 20). [nciAppModulePage]. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/genetics-dictionary/def/de-novo-mutation

- ↑ NSGC > About > About Genetic Counselors. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2025, from https://www.nsgc.org/About/About-Genetic-Counselors

- ↑ Christian, S., Somerville, M., Huculak, C., & Atallah, J. (2019). Practice variation among an international group of genetic counselors on when to offer predictive genetic testing to children at risk of an inherited arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 28(1), 70-79 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-018-0293-

- ↑ Peltenburg, P. J., Gibson, H., Wilde, A. A., van der Werf, C., Clur, S. A. B., & Blom, N. A. (2024). Prognosis and clinical management of asymptomatic family members with RYR2-mediated catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: a review. Cardiology in the Young, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951124000714

- ↑ Coll, M., Pérez-Serra, A., Mates, J., Del Olmo, B., Puigmulé, M., Fernandez-Falgueras, A., ... & Campuzano, O. (2017). Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity: hallmarks in channelopathies associated with sudden cardiac death. Biology, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology7010003