Course:LIBR548F/2010WT1/WOOD ENGRAVING

Wood Engraving

The practice of using wood as a stamp or template for printing pictures onto media such as paper has a history that dates to the tenth century and beyond.[1] Woodcuts were a prominent printing form in the fifteenth century, but it was not until the work of Thomas Bewick that the use of wood as an engraving plate came into prominence.

Woodcut technique prior to Bewick was rudimentary and often resembled folk art, with little attention paid to detail. The purpose of woodcut blocks was to quickly produce an illustration for a myriad of uses from pamphlets and catalogues to bibles and books. While traditional engravings were done on copperplate, the move to wood was beneficial for many reasons. First, it was vastly cheaper than copper and the boxwood used for the blocks was readily available. Secondly, it was infinitely easier to carve, particularly once the technology to carve against the grain came into practice in the mid-18th century.

Wood engraving began to fall out of favour in the late 19th century, mainly due to the cost of employing engravers and the decline of the mass-production of boxwood engraving blocks.[2] The tradition did continue into the 20th century, but the techniques often reverted back to woodcut and the craft mainly saw its resurgence in the mainstream artistic markets and in the folk art tradition.

Woodcut vs. Wood Engraving

Woodcut as a means of providing illustrations to text dates from even before the advent of movable type.[3] The technique is simple: remove segments of wood from the block in a design or pattern, leaving lines of relief on the surface. Once ink is applied, usually with rollers, the image will appear in the reverse of what was engraved.

Due to the large, rough cuts, any medium hardwood was used and it was carved laterally with the grain.

Wood engraving is far more complex. Utilizing techniques from the copperplate engraving tradition, the engraver would carefully etch the surface of boxwood, a semi-hard wood with a tight grain, and would carve against the grain. This technique was a vast improvement because it allowed artists to achieve the fine detail work comparable to metal.

Instead of removing large chunks of wood, engravers would score the wood in series of line and dot formations to create texture, light, shadows, detail and movement.

Tools

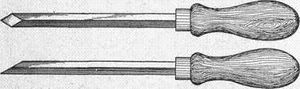

Much of the appeal of wood engraving to tradesmen was the ease with which tools could be acquired and augmented to meet the needs of each particular artist. Although some artists preferred many different tools, there was a consensus that three main tools were essential: “a graver, a spitsticker and a scorper”.[4]

The Graver

The graver was the most widely used tool.[5] The sharpened square or trapezoidal end would graze the surface of the block and with the correct pressure, remove wood in a controlled manner, while allowing the artist to see directly in front of the tip so their intended path for carving could be maintained.

The Spitsticker

This tool is specifically designed for intricate work, such as fine and curved lines. Unlike the graver, the carving edge of the tool is elliptical or convex with sharply sloping sides. This allows the tool to flow easily around corners and prevents damage and bruising of the wood as it works. This is integral not only to execute the artists’ vision, but to ensure the finished product is as flawless as possible for printing.

The Scorper

These tools are also known as “gouges or scamples”.[6] These tools were used primarily for “cutting broad white lines”[7] and for removing excess wood from white areas on the block. The blade is flat and square which allows it to be used on two sides: the small end can be used for fine white lines while the long end can be used to gouge larger chunks with clean, square edges.

Types of Wood

Prior to the late 18th century, and semi-hard wood such as cherry or pear was used extensively in the production of woodcut. The loose, erratic graining pattern was of little importance due to the fact that there was minimal detail work on wood occurring during this time. There was a discovery made, however, of using boxwood, a type of hardwood with a fine grain, and cutting the wood laterally, parallel with the ground. Pieces of the wood were affixed together in blocks and joined by tongue and groove.[8] This advance allowed carvers to experiment with detail and also allowed the tools to carve in many directions with a reduced fear of chipping or of going off course from the planned drawing because they have hit a small burr or knot. Thomas Bewick was the father of boxwood engraving.

Thomas Bewick

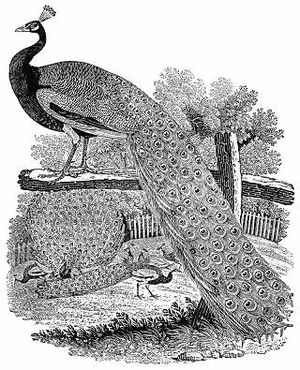

Thomas Bewick was an accomplished engraver from the city of Newcastle. He trained for seven years under a traditional metal engraver. Bewick had some experience with woodcut technique during his time under Ralph Beibly, but it was not until he discovered the versatility of boxwood and wood engraving that he found his forte and charted his own career. “When he realised that engraving on wood could be as fine as that on copper, he was filled with enthusiasm”.[9]

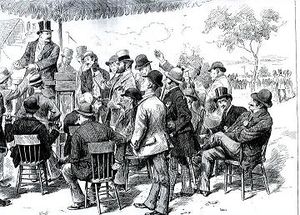

Bewick was one of the few artists of the time who was able to make a living solely from woodblock engravings. While this achievement took some time, his passion for the natural world and his illustrative studies of English quadrupeds and birds provided him an outlet to create his engraved masterpieces.

Modern Woodcut and Wood Engravings

Woodcut and wood engravings are still used today, but they have not and will likely never will achieve the widespread use of the Victorian Era. Modern artists now often print in colour and with the advancement in tool technology, the results are stunning. Wood blocks are rarely used in the illustrations of modern books, other than special or limited editions; the trade has evolved into a predominantly specialized artisan form.[10]

Notes

References

- Lindley, Kenneth (1970). Great Britain: David and Charles. Text "'The Woodblock Engravers" ignored (help); Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- deMaré, Eric (1980). London and Bedford: Gordon Fraser Gallery, Ltd. Text "The Victorian Woodblock Illustrators" ignored (help); Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Chamberlain, Walter (1978). London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. Text " Manual of Wood Engraving" ignored (help); Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Sources

1. The Woodblock Engravers. Kenneth Lindley. David and Charles Publishers: Great Britain, 1970.

2. The Victorian Woodblock Illustrators. Eric de Maré. Gordon Fraser Gallery, Ltd.: London and Bedford, 1980.

3. Manual of Wood Engraving. Walter Chamberlain. Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London, 1978.

Further Reading

4. 1800 Woodcuts. Thomas Bewick. Ed. Blanche Cirker. Dover Publications: New York, 1962.

5. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Arthur M. Hind. Dover Publications Inc.: New York, 1963.

6. English Wood Engraving: 1900-1950. Thomas Balston. Art and Technics: London, 1951.

7. Manual on Wood Engraving. L.A. Doust.Frederick Warne and Co.: London, 1948.