Course:GRSJ300/2020/Systems of Oppression: Exploring Intersectionaity

What is Intersectionality?

History

The roots of intersectionality stem from the creation of feminist theory and the histories of women’s liberation and women’s movement(s). In the early days of the movement and organization, many women began to question whether the experience around the creation of feminist theory was the same for everybody. This sparked opening of conversation surrounding the idea that there is no set body of feminist principles and beliefs.

bell hooks is an influential American scholar who published writings on the connections between race, gender, and class. She used her own experiences and understanding to publish theories and ideas that prompted many to think critically about whose voices were being heard. There began the discussion of white women from privileged class backgrounds having priority over black women and women of color. At the time, discussing this priority was seen taking away from the purpose of the movement. However, this examination of the interlocking nature of gender, race and class was the perspective that changed the direction of feminist thought, and ultimately lead to its continual development.

A collection of Black feminists named The Combahee River Collective also believed in this interlocking nature of their oppressive experiences. They recognized the existence of racial-sexual oppression which is neither solely racial nor solely sexual[1]. They believe the synthesis of these oppressions created the condition of their lives.

The Term Intersectionality

Kimberlé Crenshaw is the individual who coined the term intersectionality. She recognized the multidimensionality of Black women’s experience and the theoretical erasure of this experience through single-axis analysis[2]. Intersectionality has been recognized as a matrix rather than a cumulative identity formula containing separate factors such race, gender, class, sexuality, (dis)ability, citizenship status, and so on. It is seen as complex and heuristic in nature[3]. Intersectionality is also acknowledged as contextual in its ability to highlight how one’s identities, structural systems of marginalization, forms of power, and modes of resistance “intersect” in dynamic shifting ways[3]. Intersectionality is a lived experience developed through decades of personal and political struggle, oppression, testimonials, research, movements, and so on, rather than a static theory.

Power and privilege work in an elastic nature and more lived experiences occur daily. That is why the concept of intersectionality is seen as a fluid framework that continues to develop to this day. It is meant to be applied reflexively and in an ongoing contextual way[4]. For this reason, the definition of the term is not singular, but multidimensional and complex.

Applications of Intersectionality

Social Movements

Social movements are an important tool in challenging systems of oppression and informing cultural change. Intersectionality as a framework stemmed from early black feminist social movements and continues to be applied within social justice organizations as a tool in highlighting the intersection of factors including race, class, gender, sexuality, and (dis)ability- and their contribution to systems of privilege and oppression.

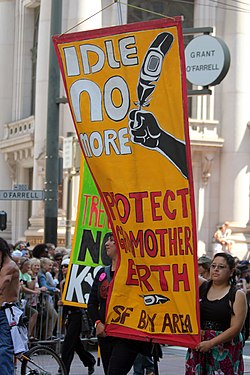

Idle No More

The Idle No More movement focuses on bringing awareness to the systemic injustices and oppressions that Indigenous folk experience. Many of the oppressions stem from the actions of colonialism, which have caused and accelerated dispossession within Indigenous communities[5]. We see, especially in the COVID-19 era, that organizing has relied heavily on social media for communication and community building. Some argue that this takes away from the bodymind connection and works in an Cartesian manner to express only the mind[5].

An intersectional framework is important when speaking toward Indigenous experiences, as we see their identities, body and mind, contributing to multiple layers of oppressions. For example, Indigenous women are 4 times more likely to be murdered and 2.5 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than non-indigenous women[6]. This points towards the importance of applying and acknowledging intersectionality within the Idle No More movement. Moving away from single-axis identities, Indigenous Women’s experiences are not only distinct from non-indigenous women, but also from one another.

Black Lives Matter

The Black Lives Matters movement was founded in response to the unjust killings of black folk by police. Since its founding in 2013, the movement has brought light to the systemic issues that lead to the disproportionate violence against black folk. The movement works toward fighting for the lives of all black people, especially focusing on those experiencing multiple oppressions[7]. We see these multiple oppressions highlighted in the experiences of black-trans folk, who are often a target in racist and sexist violence. Intersectional tools have been vital in the Black Lives Matter movement in bringing light to the systemic issues faced by trans, queer, non-binary, and disabled people of color[7].

Asian Immigrant Women Advocates

Asian Immigrant Women Advocates (AIWA) came together in recognition of the treatment of Asian women in low-paid factory jobs in the San Francisco area[8].This movement acknowledges the intersection of sexism, classism, and language discrimination as all contributing to their experiences of oppression. These ideas have moved them to finding new ways to invigorate change and develop toward inclusivity in their communities by challenging the power systems that oppress them.

Academia

Beyond the study of intersectionality, utilizing an intersectional framework within academia is important in developing programs and encouraging representation within institutions to challenge ongoing systems of oppression.

In thinking toward reconciliation within Indigenous communities, an intersectional framework is vital in acknowledging the multitude of oppressions that have resulted from white colonialism and its systems that exacerbate oppressions. Specifically in academia, Linda Tuhiwai Smith calls for recognition of Indigenous ways of knowing not to be subordinate to scholarly knowledge[9]. Beyond the racial, gender, and class oppressions, Indigenous culture has been historically suppressed in an academic setting, most notably the existence of residential schools. Smith’s call for acknowledgment and application of the cultural knowledge production of Indigenous peoples works to redefine the colonial ways of knowing within academia, moving away from Cartesian thinking and settler colonialism[5].

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, author of Talkin’ Up to the White Women, has become an important figure for Indigenous women in Australia [10]. Moreton-Robinson urges white women scholars to move beyond theorizing of giving up power, and to open up these spaces for Indigenous women, who are at the intersection of multitudes of oppressions. In doing so, Moreton-Robinson has uplifted Indigenous women within academia, while also advocating for Indigenous methodologies and knowledges in scholarship[9].

COVID-19

In coming together as a group to discuss ideas, the presence of the systemic oppressions of those affected by COVID-19 are apparent. Everyone in the world is being affected by COVID-19, but many are experiencing it in different ways reflective of their social location. Using an intersectional framework allows us to view the differing systems of oppression and privilege that individuals hold and to think how this affects the world around us.

Data from the COVID-19 tracking project has highlighted the disproportionate rate of people of color experiencing and dying from the virus within the United States[11]. Beyond race, the experiences of people affected by COVID-19 are informed by a multitude of underlying oppressions. These racial disparities stem from a multitude of systemic issues, including access to healthcare, increased risk of occupational exposures, and historic mistreatment of marginalized communities in healthcare [12]. In order to address this social injustice, an intersectional analysis is necessary to take action on the multiple oppressions that are contributing to the disproportionate suffering of people of color.

LGBTQ+ individuals are experiencing many of the struggles that come with a pandemic; including loss of jobs, homelessness, and accompanying lack of health insurance. In a system that is already biased against the LGBTQ+ community, additional stressors have exacerbated systemic oppressions and further increased mental health issues [13].

Visibility of Intersectionality in Popular Culture

Intersections of Identity

The framework of intersectionality can be seen in popular culture such as film, television shows, music, books, and social media. We can see intersectionality in popular culture by analyzing how forms of popular culture inform people about certain issues/problems, such as systemic oppression individuals may face because of their identity. "Film is [...] a powerful medium impacting consciousness of race, class, gender, sexuality and other intimate aspects of human life"[14]. Therefore, when films address issues individuals may face that are often not displayed in popular culture, it can become a powerful tool of awareness for individuals. We also see intersectionality in popular culture when "it invites us to think from "both/and" spaces and to seek justice in crosscutting ways by identifying and addressing the (often hidden) workings of privilege and oppression"[15]. We can see "both/and" spaces in films such as Moonlight (2016), where the main character isn't affected by just their race, but also their sexuality and gender. Popular culture can allow audiences to view how individuals can be affected by multiple aspects of their identity at once, and shed light on the oppression that these individuals may face. Popular culture allows viewers to see how individuals don't live singular-axis lives, and this is important to recognize individual's differing experiences based on their identity.

Within-group Differences

Popular culture allows us to view differing experiences amongst a common group, demonstrating that people don't live singular-axis lives. May states, "[intersectionality] attends to within-group differences and inequities, not just between-group power asymmetries"[16]. The television show, Orange is the New Black, is an example of how we see intersectionality in popular culture by displaying the within-group differences that the African American women in the prison face. The African American characters in Orange is the New Black display differing identities, such as transgender and gay women, and how these individuals have different experiences compared to other African American inmates based on their identity. As "highly specific characters like Sophia [who is transgender], are powerful reminders that there are many ways to be black, or to be a woman"[17]. The systems of oppression are not equal amongst one common group, as an individual can be faced with multiple systems of oppression within their identity.

Dismantling of Stereotypes

We can also see intersectionality in popular culture by who is being represented on the screen and how. Having multiple experiences from people of different genders, disabilities, sexual orientations, ethnicities, and classes visible in popular culture is important as it allows a space where these individuals may not often be represented. Seeing differing experiences in popular culture allows for stereotypes to get dismantled depending on how individuals are being portrayed. For example, the film Hidden Figures (2016), demonstrates an empowering film challenging the false stereotypes about African American women as they work at NASA with their challenging experiences in the workplace because of their identity. As a woman in STEM, we often see men represented as scientific prodigies or geniuses; so representation of women of color dismantling this stereotype not only breaks typical on-screen representation, but also speaks to and inspires young women, like myself, who wish to pursue careers in male dominated fields.

Challenges and Critiques of Intersectionality

Challenges in Academia

The issues with Intersectionality and academia stem from a tendency in academia to discuss theoretical implications rather than practical. In academia, intersectionality can tend to focus on can/might be/do, or can/might not, be/do[18]. This focus on intersectionality in the abstract can fail to show what the framework actually does in research, and what researchers can accomplish using an intersectional framework. The problem here is that academia can confine intersectionality to an, “overly academic contemplative exercise”[19], instead of as a tool that can be actively used to fight against the systems of oppression that it identifies.

"Whitening" of Intersectionality

The whitening of intersectionality refers to consistent attempts from people of privilege to move away from the black feminist origins of intersectionality and therefore away from the problem itself. Particularly in Europe, but also in North America, intersectionality is often seen as the “brainchild” of feminist theory[18]. That the rise of traditional white feminism directly created intersectionality. This view erases “intersectionality's intersectional origins”(p.19) [19], which downplays the importance of race in the creation of intersectionality, and also hides the historic tensions between traditional feminism and women of color in the regards to the origin of the theory.

The whitening of intersectionality also refers to the idea that the genealogy of intersectionality needs to be broadened. These ideas of political and theoretical reframing of intersectionality inherently question whether the framework should be seen as valid, or merely as a heuristic device. This leads to consistently devaluing the significance of intersectionality produced by feminists of color because it assumes that radicalized women’s experiences cannot generate theory and therefore can only be understood as a descriptive collection of experiences[18].

Intersectionality Wars; Critiquing Intersectionality

It can be hard to critique intersectionality because critiques are often seen as for, or against intersectionality, and therefore for or against black feminism, and subsequently for or against black women themselves. This issue creates an environment where discussing the nuances and refinements of intersectionality can be difficult. This ensures that discussing the limits of intersectionality almost always becomes a debate on racial politics and allegations of intolerance. This disregards valid criticisms of the theory that include the idea that it can tend to be too focused on race/gender, which therefore prevents real social movement on systems of oppression that intersectionality could, and should disrupt[20].

The language that is used when discussing the appropriation of intersectionality, specifically the “whitening of intersectionality” also raises important questions. The most relevant of which is how the appropriation of intersectionality differs from the migration of ideas through academic circles[20]. Because of this there is an idea that only women of color, or even black women exclusively, have the right to discuss the framework of intersectionality, which limits who can rightfully access the analytical tools of intersectionality, and labels anyone who goes against that notion as critic, and an enemy of intersectionality in general.

Conclusion

The term intersectionality carries a rich backstory that stems from a recognition of the multidimensionality of Black women’s experiences, as well as the exacerbation of these oppressions through single-axis analysis. Intersectionality has developed through decades of political, economic, social, racial, and sexual oppressions and struggles. It has rendered itself applicable to numerous social movements, many aspects of popular culture and to the current COVID-19 pandemic where systemic oppressions have become further evident.

Intersectionality continues to evolve through lived experiences, dilemmas, and contradictions as a fluid framework, rather than a static theory. The framework is utilized to this day as a lens to critically analyze powerful and oppressive systems and institutions that shape most political, economic and social structures within our society.

References

- ↑ Combahee River Collective (1983). This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Kitchen Table, Women of Color Press: New York. pp. 210–218.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1997). "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics". Feminist Legal Theories. Routledge.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 May, Vivian M. (2015). Pursuing intersectionality, unsettling dominant imaginaries. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 18–62.

- ↑ May, Vivian M. (2015). Pursuing intersectionality, unsettling dominant imaginaries. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 1–17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake, Rinaldo Walcott and Glen Coulthard. “Panel Discussion: Idle No More and Black Lives Matter: An Exchange.” Studies in Social Justice12, no.1 (2018): 75-89.

- ↑ "Indigenous Women's Rights are Human Rights".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "About Black Lives Matter".

- ↑ Chun, Jennifer, et al. Intersectionality as a Social Movement Strategy: Asian ... 2013, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669575.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “Towards an Australian Indigenous Women's Standpoint Theory: A Methodological Tool.” Australian Feminist Studies 28, no. 78 (2013): 331-347.

- ↑ "I have never stopped Aileen Moreton-Robinson on 20 years of Talkin' Up to the White Woman".

- ↑ "As Pandemic deaths add up racial disparities persist and in some cases worsen".

- ↑ Berchick, Edward R., Jessica C. Barnett, and Rachel D. Upton Current Population Reports, P60-267(RV), Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2018, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2019.

- ↑ "Discrimination Racism fuel covid 19 Woes".

- ↑ Edwards, Erica B., and Jennifer Esposito. Intersectionality Analysis as a Method to Analyze Popular Culture: Clarity in the Matrix. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019, pp. 123.

- ↑ May, Vivian M. “What is Intersectionality? Matrix Thinking in a Single-Axis World.” Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries, New York: Routledge, 2015, pp. 21.

- ↑ May, Vivian M. “Introduction: The Case for Intersectionality and the Question of Intersectionality Backlash.” Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries, New York: Routledge, 2015, pp. 4.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Alyssa. “How ‘Orange is the New Black’ wins at illustrating identity,” The Washington Post, The Washington Post, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2015/09/22/how-orange-is-the-new-black-wins-at-illustrating-identity/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Bilge, Sirma (2013). Intersectionality Undone. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. pp. 405–424.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Luft and Ward, Rachel E. and Jane (2009). Toward an Intersectionality Just Out of Reach: Confronting Challenges to Intersectional Practice. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 9–37.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Nash, Jennifer (2019). Black feminism reimagined: after intersectionality. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 33–58.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |