Course:GRSJ300/2020/Media Representations of Intersectionality

Understanding Intersectionality

Moving Away from Singular-Axis Thinking

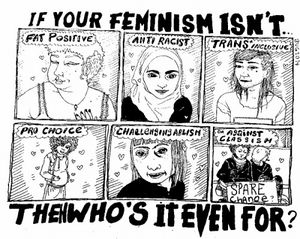

In order to understand the benefits that an intersectional framework can offer, it is first necessary to recognize the limitations of utilizing a single axis framework to analyse the experiences of black women and women of color, particularly under feminist contexts. The single axis framework currently utilized by many feminist doctrines are fundamentally exclusionary and privilege-based in their disregard for the possibility of belonging to multiple marginalized groups simultaneously. As Kimberle Crenshaw denotes, the single-axis framework simplifies the intersectional experience by centering its interrogations around the relatively privileged members of a single marginalized group: for example, interrogations into racial discrimination are primarily centered around the experiences of upper-class, black men, and interrogations into gender discrimination are primarily centered around the experiences of upper-class, white women (Crenshaw 24)[1]. Consequently, the intersectional experiences of black women and women of color who do not share the same class or heteronormative benefits risk being absorbed into the mainstreaming of privileged experiences (27)[1].

Intersectionality and The Glass Ceiling

The glass ceiling was a popular metaphor used within feminist movements to initially illustrate gender-based exclusion as an “invisible barrier” in the workplace that prevents women from rising to higher-level career positions (Barreto et al. 5)[2]. Later, the term was evolved by the state commission to become inclusive of other disadvantaged demographics, however failing to address membership within multiple disadvantaged groups (6)[2]. Crenshaw’s intersectional analysis expands upon the notion of the glass ceiling, suggesting that even within those who are “trapped” under the ceiling, disadvantage continues to be hierarchically organized on the “basis of race, sex, class, sexual preference, age and/or physical ability” (Crenshaw 35)[1]. Crenshaw’s metaphor characterizes a “stacked” hierarchy that relegates those affected by multiple disadvantages at the bottom, while allowing those who are only disadvantaged by one factor the opportunity to sometimes rise above the ceiling amongst those who are not disadvantaged at all (36)[1]. Intersectional analysis seeks to expose the experiences of those affected by multiple avenues of disadvantage from becoming absorbed into the “universalized” representation of the relatively privileged (May 22)[3].

Intersectionality as Imaginative Resistance

Vivian May’s explanation of intersectionality and it's multifaceted nature encourages the intersectional framework to be viewed as a social discourse that imagines alternative futures to that of the dominant narrative. Intersectionality thus allows for intervention with and resistance against historical memories that continue to establish contexts of inequality and white dominance (May 34)[3]. Given its political potential, intersectionality offers a radical shift towards equity rather than equality for those affected by intersectionality under contexts of social interrogation (35)[3]. A key example of the necessity for the intersectional framework is Becca Cragin’s criticism of early feminist talk shows, which often produces contradicting results by valuing entertainment over therapy, social change, and reimagination (Cragin 156)[4]. Cragin’s analysis looks specifically into the representation of queers in talk shows, which fluctuates drastically depending on their race and class (163)[4]. For example, “lesbian chic” is reserved mainly towards upper class, white women (168)[4]. Under such contexts, the intersectional framework would benefit by revealing and interrupting dominant social narratives by recognizing representational differences.

Representation of Intersectionality in Media

Intersectionality has made its way into various forms of media. Not only is it often discussed in social media, but it is also seen within movies and TV shows, highlighting the multiple layers of discrimination that people face. There is, however, a difference in how intersectionality is taken up depending on the medium in which it is delivered. Books, articles, and journals can easily present descriptions of the theory and outline its emergence and history, but these types of literature do not have much exposure, and are likely encountered by those who seek it out, or university students who wish to learn about intersectionality. Then, the main way in which intersectionality can reach a wider audience is through popular media. Recently, there has been great representation of intersectionality within film and television shows. Below are some ways in which intersectionality can be taken up by the media.

Films

As films are restricted to a time limit of 90 – 100 minutes to convey their stories, movies that make use of an intersectional framework often focus on more specific groups at a time. For example, the movie Moonlight focuses on the interlocking forms of discrimination faced by people who are both black and homosexual (Allen 596)[5], while the movie The Help focuses on the discriminations faced by black women (Lee and Preister 94)[6]. As is evident, it is difficult to tell a story on different combinations of discrimination, else it would risk blurring the focus of who the movie is trying to highlight. As Moonlight won several awards, including best picture, it shows that movies that take up intersectionality can reach a wider audience apart from those who can relate to the specific experience. Intersectionality is taken up in films to make visible those who are under several layers of prejudice, and to make this idea available for general audiences.

TV Shows

Although TV shows can run much longer than movies, providing more time to explore a wider range of people who are affected by different combinations of discrimination, they have a bad track record of treating characters on a single axis. A study on 22 TV sitcoms found that representations of homosexual characters made significantly more comments about their sexuality, which shows that these characters are often treated on a single axis (Fouts and Inch 41)[7]. As TV shows are broken up into smaller time frames that span multiple episodes, they do not have the focus required to effectively take up intersectionality as movies do. However, some shows like Brooklyn Nine-Nine have successfully utilized an intersectional framework, by revealing the multiple layers of discrimination over the span of a season, allowing for character development and the representation of intersectionality. As viewers come to be more familiarized with the struggles of a character, TV shows can convey intersectionality more personally compared to movies.

It is apparent that intersectionality can be taken up in different ways, depending on the type of media that is being used. Movies take up intersectionality to highlight specific groups and to tell a story using an intersectional framework within a limited runtime. TV shows, on the other hand, focus on characters and expose their struggles over a longer stretch of time, as they have longer runtimes broken up into shorter episodes. Either way, intersectionality can be taken up by different forms of media to make the framework widely available for general audiences.

Challenges Facing Intersectionality

Neutralization Through Contemporary Feminism

As a framework, intersectionality comes with its own set of challenges. Some challenges faced by intersectionality involve power relations between varying political ideologies (Bilge 406)[8]. In academic feminist discourse, for example, there exists a depoliticization or neutralization of intersectional frameworks, which effectively moves away from the history of intersectionality and acts as an obstacle towards its goal of affecting “social justice-oriented change” (Bilge 405)[8]. Intersectionality has been largely praised by feminist scholars as the “best feminist practice”, and has been used to establish the contributions of feminist knowledge to various disciplines in academia by re-framing the theory so that it is viewed as a component of feminism (e.g. intersectionality as the “brain-child” of feminism) (Bilge 406)[8]. Rethinking intersectionality as a subset of feminism is an attempt made by feminism to effectively contain and take over the ideology. In doing so, the radical political context in which intersectionality was born is ignored. Furthermore, rethinking intersectionality as belonging to feminism ensures its politics are neutralized, as feminist control over intersectionality allows intersectional frameworks to be implemented in ways that benefit White feminist scholars, and turning the theory into an “overly academic exercise” (Bilge 411)[8] deters the use of intersectionality as an analytical tool to be used to affect real change. This is evident in media reception of films involving intersectional theory and frameworks, for example, where such films are often praised for their feminist implications while the role of intersectionality is reduced to a mere aspect of feminism that shined through within the film (or is ignored altogether).

Neoliberal Approaches to Diversity

In addition to the challenges faced by intersectionality within contemporary feminist discourse, neoliberal approaches to diversity present a different set of challenges and further facilitate the erasure of the history of intersectionality, while neutralizing its politics. Neoliberal discourses surrounding increased diversity promote the notion that Western societies have somehow overcome issues regarding racism, sexism, and homophobia (Bilge 407)[8]. This is of course false, and encourages a disregard for deeper, more entrenched systems that continue to oppress by promoting racial blindness. This is a fundamental odds with the core ideas that intersectionality bases itself on. Encouraging individuals to be “color-blind” takes away from intersectionality, which necessitates that intersections of race, gender, sexuality, class, ability, and citizenship status be examined as a means of dismantling oppressive systems. This also encourages the history of intersectionality to be overlooked, as there is no perceived need to revisit complex political histories if problems relating to racism, sexism, and homophobia have been “solved”. In addition, “color-blind” neoliberal narratives promote hegemonic knowledge, which facilitates an ornamental approach to intersectionality wherein intersectionality is used opportunistically and superficially (Bilge 408)[8]. This undermines both the credibility of intersectionality and its political potential, as ornamental intersectionality presents opportunities to engage with performative activism while ignoring the deeper, interlocking oppressive systems that perpetuate injustice. This is evident in the film industry, with organizations such as the Hallmark channel, a popular channel for Holiday movies, posting a public statement in support of the Black Lives Matter movement while failing to address the racist systems their exclusively White casting upholds. These challenges are further amplified by a lack of accessibility to intersectional approaches and frameworks, as intersectional theory is most accessible to individuals that are able to receive some form of higher education.

Intersectional Analysis of Women of Colour in Popular Culture

Race-Based Appearance Discrimination Experienced by Women of Colour in the Film Industry

Lack of an intersectionality framework in the media industry may contribute to the presence of prejudice and discrimination faced by women of color. When addressing racial discrimination faced by women of color in this industry, another narrower issue that should be concerned by the general public is the association between appearance and treatment. Several studies have shown that appearance could impact one’s overall career success (Rashbrook)[9]; moreover, individuals with nice appearance also report having more positive experiences. However, the beauty standard, especially the standard for women, is often defined by western culture and based on white women, for example, pale and skinny, with lower waist-to-hip ratios. For women who do not satisfy these beauty standards, they are treated and perceived with bias by the general public.

This race-based appearance discrimination phenomenon could be illustrated by Halle Bailey’s experience of chosen as the actress for The Little Mermaid movie. Halle Bailey is a young actress from African American descent. Disney officially announced the casting of Halle in 2019 for the role of the mermaid princess in their movie “The Little Mermaid”. Soon after the announcement, aggressive comments started to appear on different media platforms. The comments generally contained negative contents attacking Halle’s appearance, namely her skin color, and ignored her suitability and professionality as an actress. Halle’s experience demonstrates the situation that actresses face when their appearance does not fit the general public’s beauty standard, but we do not see those same controversies relating to white actresses' appearance when they are chosen for an acting role.

The victims of race-based appearance discrimination are in general women of colour, including Black actresses and Asian actresses. The primary reason behind this phenomenon is that our perception of beauty is shaped by Western cultures, leading to the current trend of women of colour facing a more rigid standard than white women within the film industry. Historically, Black women have faced a significant amounts of injustice in the film industry; their images were once missing from science, politics, mainstream culture and several other areas. Black feminist scholars once made the argument stating the marginality that Black women face is primarily due to lacking media depiction images (Terry)[10]. Yet, based on the fact that the current beauty standard is shaped by Western culture based on White women’s look, when Black women are incorporated into the media, they still face controversies and unreasonable criticisms based on both their skin colour and their physical appearance. Due to stereotypes associated with Black women, the phenomenon of rating a celebrity according to her skin color extends further, outside of Western culture. Similarly, in Chinese media industry, a female celebrity Ju Wang, who has a slightly darker complexion, constantly receives public criticisms. Wang's physical experience leads to people believing that she does not qualify as a celebrity nor as an actress.

In short, the movie industry significantly lacks an understanding of the intersectional framework to address the hardship and prejudice faced by actresses of color.

Singular-Axis Representations in Film and Television

Intersectionality in media is necessary as it brings awareness to the framework in an accessible manner. Intersectionality through media is not only accessible to a broad audience but is also useful in combating stereotypes that are often perpetuated without an intersectional lens. There are various types of intersectional bodies represented in pop culture which are found especially within television and films. A few examples of intersectional bodies are; disability activism, women, people of color, LGBTQIA2S, and countless more. By drawing on the intersectionalities of women and women of color, we are able to observe the need for a more developed intersectional framework in pop culture. When representing women in media, an intersectional lens is required to avoid stereotypes and prejudice.

Often, women are subjected to supporting roles that fill stereotypes such as the housewife, maid, or nurses. The fact that women are subjected to smaller roles leads to less representation in the media workforce (Rattan et al.)[11]. Currently, Women only represent a quarter of the media workforce (Rattan et al.)[11]. The presence of women in media is highly disproportionate to males and this only touches on representation and not equality in the types of roles played. Intersectionality is beginning to shine as women increasingly gain leading roles in movies and television. For example, Ocean’s 8 debuted in 2018 featuring a cast of eight diverse women. An all-female cast breaks the boundary that the Ocean’s franchise is a “boys club”. These women are seen to defy stereotypes as they portray strong women who each carry their own intersectionalities.

Women of color have especially felt the lack of an intersectional framework in media, often utilized to play stereotypical roles (Crenshaw 39)[1]. These women also face countless stereotypes due to single-axis perspectives (Rattan et al.)[11]. For example, the Mindy Project follows Mindy Kaling as she navigates the world as a professional South Asian woman in New York City. Her character is subjected to countless stereotypes due to being a woman of color. To illustrate, she is portrayed as weak and emotional while dealing with a breakup as she is a woman. A stereotype associated with her being a woman of color is that her place in a doctor’s office is seen as unusual when compared to her white male counterparts. These harmful stereotypes perpetuated in the Mindy Project are unproductive as they don’t reflect an intersectional lens. In speaking to our group, we did not observe the stereotypes and need for an intersectional framework as we were just ecstatic to see representation from characters that looked like us on television. After learning more about intersectionality, we realized it is important to not correlate representation as intersectionality.

In conclusion, media has improved vastly in regards to representation but needs to further progress in representing characters as intersectional beings and not through a singular axis lens. Despite this, the singular axis lens is seen through stereotypes perpetuated in popular culture (Crenshaw 47)[1]. The future progression of women in media is proving successful as some companies have begun to meet a 50:50 ratio (equal percentage of women and men) where previously the numbers were disproportionately in favor of men in media (Rattan et al.)[11]. An intersectional framework will improve popular culture in making characters and storylines more complex and accurate to real-life individuals.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” Feminist Legal Theories, edited by Karen Maschke, Routledge, 1997.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Barreto, Manuela, et al. “Introduction: Is the Glass Ceiling Still Relevant in the 21st Century?” The Glass Ceiling in the 21st Century: Understanding Barriers to Gender Equality, American Psychological Association, 2009, pp. 3-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 May, Vivian M. “What is Intersectionality? Matrix Thinking in a Single-Axis World.” Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries, Routledge, 2015, pp. 18-62.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cragin, Becca. “Beyond the Feminine: Intersectionality and Hybridity in Talk Shows.” Women's Studies in Communication, vol. 33, no. 2, 2010, pp. 154-172.

- ↑ Allen, Samuel. “Moonlight, Intersectionality, and the Life Course Perspective: Directing Future Research on Sexual Minorities in Family Studies: Moonlight Review.” Journal of Family Theory & Review, vol.9, no.1, 2017, pp. 595–640.

- ↑ Lee, Eun-Kyong Othelia, and Mary Ann Priester. “Who Is The Help? Use of Film to Explore Diversity”. Journal of Women and Social Work, vol.29, no.1,2014, pp. 92–104.

- ↑ Fouts, Gregory, and Rebecca Inch. “Homosexuality in TV situation comedies: Characters and verbal comments”. Journal of Homosexuality, vol.49, no.1, 2005, pp. 35-45.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Bilge, Sirma. "INTERSECTIONALITY UNDONE: SAVING INTERSECTIONALITY FROM FEMINIST INTERSECTIONALITY STUDIES." Du Bois Review 10.2, 2013, pp. 405-24. ProQuest.

- ↑ Rashbrook, Oliver. "An Appearance of Succession Requires a Succession of Appearances." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 87, no. 3, 2013, pp. 584-610.

- ↑ Terry, Brittany A. The Power of a Stereotype: American Depictions of Black Women in Film Media, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Rattan, Aneeta, et al. “Tackling the Underrepresentation of Women in Media.” Harvard Business Review, 8 July 2019.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |