Course:GEOS303/2023/Hawaii

Introduction

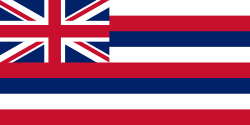

Hawaii is the only U.S. state outside North America. It is comprised of 137 islands, with the eight main islands being Hawai'i, Maui, O'ahu, Kaua'i, Moloka''i, Lānaʻi, Niʻihau, and Kahoʻolawe. Hawaii stands as the world's most isolated archipelago, residing over 3,200 kilometers from the enarest continent in the vast Pacific Ocean.[1] Because of its extreme isolation, coupled with distinctive climatic conditions, Hawaii has a high level of endemism, with 10,000 species exclusive to the islands.[1] Although thousands of Hawiian species are yet to be described, it is estimated more than 14,000 terrestrial, 100 freshwater, and 6,500 marine taxa are native to the region.[1] This ecological treasure faces challenges, including the impact of human activities, invasive species, and the delicate balance between conservation and development. Efforts to protect and preserve Hawaii's natural wonders through initiatives such as Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS), recognizing the need to safeguard native species and their habitats.[2]

Climate and biomes

There is a wide range of biomes that can be located on the Hawaii islands in relation to its diverse topography, physiognomy, and various climates across the archipelago. It is recognized that generally in the Hawaiian archipelago, the seasons can be classified into two main categories; “warmer and drier summers happens between May and September whereas the “slightly cooler and wetter winter” typically occurs between October and April [3]. Below lists the most dominant terrestrial biomes, exploring some of the unique characteristics of these landscapes that make up Hawaii.

Tropical Moist Forests:

Looking at the tropical moist forests of Hawaii, consisting of a mix of mesic forests, rainforests, wet shrublands, as well as bogs that can be located among the swampy regions.[4] The biome can be spotted along the higher mountain areas of the larger islands of Hawaii and on the mountain tops of the smaller islands; more specifically, they can be found on the island of Kaua’i, Moloka’I, O’ahu, western region of Maui, as well as in the Volcanoes National Park located in Hawaii.[4] The tropical moist forest biomes of Hawaii are also recognized for having a variety of forty-eight different forests and over a hundred native tree species that can be identified within the ecoregions of the Hawaiian islands; furthermore, with its most abundant tree species found in moist forests being the Koa (Acacia koa) and ‘Ohi’a lehua.[4] This further establishes the significance of tropical moist forests and the various biodiversity and habitats that rely on its ecological resilience to allow for its species to thrive.

Tropical Dry Forest:

Tropical dry forests tend to be found on the leeward side of the mountains due to it being drier by nature due to the neighboring volcanoes. Hawaii’s tropical dry forests have an abundant species richness with 109 different tree species amongst 29 different families with a recorded amount of 90% of them being listed as species endemic whereas the remaining 10% can be considered as indigenous; Furthermore when examining the total amount, it can be said that 37% are single island endemics[4]. Unfortunately, this region can be categorized as endangered due to the practices of burning for agriculture purposes, the introduction of invasive livestock and species that were packaged with the settling of human activity.[4] Due to these factors that are damaging the tropical dry forests of Hawaii, there have been record of species going to be or have gone extinct and so this should serve as a call to action to the public to continue to raise awareness surrounding this matter and to find opportunities to make a positive impact in conserving these ecoregions.

Tropical Low Shrublands:

The tropical low shrublands of Hawaii occur on the lowest points of the leeward slopes and can be categorized as the driest amongst lowland habitats;[4] a common trend we can see is how lowland as well as leeward areas are often more commonly faced with impacts of the sun and dryness.[3] This ecoregion experiences minimal level of rainfall which can be found to occur during its periods of "wetter winters", however, leaving the summer periods to encounter the potential occurrence of drought[4]; Furthermore, a contributing factor to the drought can be from the trade winds that are stronger in the summer where the wind can be continuously blowing for varying durations - ranging from ongoing consistent blows to being absent for weeks which consequently can create the dryness[3]. The Hawaiian tropical low shrublands has high levels of biodiversity with over 200 species of shrubs, grasses, ferns, as well as plants being unique to this ecoregion[4]. Despite the wide array of species found in the tropical low shrublands, this ecoregion is being consistently degraded and cleared due to anthropogenic activities that fall under the reasons of fire, urban development, off-road vehicles, invasive plant and animal species[4]. When looking at the low shrublands located around the coast, we can examine a higher level of vulnerability to negative impact of invasive animal species in this ecoregion as well as the continuous damage caused by off-road vehicles[4]. It is important to take proper action in limiting the damage caused by trampling from animals and from off-road vehicles to further provide safety and restoration towards the tropical low shrublands.

Tropical High Shrublands:

In this ecoregion, there is a strong presence of ‘ahinahina which through evolution, has been able to adapt and tolerate the arid and cold conditions that are faced at the peak of some of the tallest volcanoes of Hawaii[4]. The alpine deserts, alpine grasslands, and shrublands in the tropical high shrublands are the key supporters and providers to mosses, lichens, as well as the dominant species, ‘ahinahina; Similarly to the patterns of threats noticed in the lower tropical shrublands, we are able to see high grazing and trampling activity from wildlife, as well as wildfires and damages caused by off-road vehicles[4]. Due to these species being located in higher elevations that often encounter less casual disturbances, they are more susceptible and vulnerable to means of interference.

Diversity

Hawaiian Biogeography and Endemism

The Hawaiian Islands, situated in the central Pacific Ocean, boast a rich and diverse biogeographic landscape characterized by unique endemic species and intriguing evolutionary processes. Various studies have shed light on the distinct endemism levels and biogeographic patterns of different taxa within the Hawaiian archipelago. The endemism level for Hawaiian non-marine algae was estimated to be 5%, indicating a relatively low rate compared to other organisms.[5] Notably, marine red algae, marine invertebrates, ferns and lycophytes, flowering plants, and insects exhibited significantly higher levels of endemism, highlighting the diverse nature of the Hawaiian biota.[5]

Unique Evolutionary Processes and Local Radiations

The isolation and dynamic speciation processes in Hawaii have led to the development of significant local radiations of taxa.[6] Drosophilid flies, honeycreepers, and silverswords are among the many taxa forming clusters of phylogenetically related species, illustrating the fascinating evolutionary dynamics in this isolated ecosystem.[6]

Origins of the Hawaiian Flora

Studies on the origins of the Hawaiian flora suggest diverse sources of lineage, with a substantial proportion originating in the Indo-Malayan region.[7] Notably, a large majority of plant lineages were introduced to the Hawaiian Islands via bird dispersal, both externally and internally.[7] The association of external bird dispersal with a North American origin further underscores the complex biogeographic history of the islands.[7]

Human influences

Pre European Contact

At around the years 800 A.D, Polynesians colonized the Hawaiian Islands who brought with them 40 species of plants and 4 species of animals.[8] With this arrival, the newly settled population became the development of intensive agriculture resulting in two distinct types of agricultural systems merging: the Wetland Taro Systems and Dryland Field Systems.[8] Wetland systems were present on the geologically older islands, whereas the dryland field systems were located on younger islands.[8] Dryland forests were located on the leeward side of mountains and forests were cleared in order to make way for further expansion.[8] Despite the growth of agriculture on the Hawaiian Archipelago, most forests on the islands avoided the fate of intensive agricultures due to the fact that their forests soils were not particularly fertile and lacking in phosphorus content.[8]

Post European Contact

When the first European settlers arrived on the archipelago, the native Polynesians experienced a population collapse due to the introduction of many Old World diseases.[8] The resulting left many old inland settlements abandoned and paved the way for European ranching cattle to roam free in these now depopulated areas.[8] Trade between Europeans and the native Polynesians spurred the development of a lucrative sandalwood and whaling industry.[8] The growth of these industries and the introduction of ranching resulted in the destruction of many lowland dry forests due to increasing demand for wood as fuel and in turn transformed many of these areas into plains for ranching.[8]

Growth of the Sugar and Plantation Economy

Between the years 1850 and 1920, major ecological change was primarily driven by the introduction of industrial agriculture, with sugar being the primary crop due to its extremally lucrative returns.[9] Hawaii would become the most efficient producer of sugar in the world with each acre producing an average of 93 tons of sugar.[9] Additionally, during this time period the plantation area would grow from 10,000 acres to 236,000 acres by 1920.[9] Cultivation of sugar was both a labour and water intensive process.[9] Extreme water usage for these plantations had widespread impact on the ecology of the islands and was not limited to the plantations themselves.[9] One major change was that the logging of forests for plantation space greatly reduced the amount of local rainfall as the lack of trees reduced the amount of moisture available in the area.[9] Forest lost was also driven by the need for space for ranching and grazing area.[9] This loss in precipitation would begin a period of frequent droughts on the islands of Hawaii.[9] Although many of the plantations are now absent, there ecological impact is still felt due to amount of water usage and deforestation.[9]

Effects of Military Usage

The island of Kaho'olawe is the smallest main island that makes up the Hawaiian Archipelago and has a history of extensive use by the United States Armed Forces.[10] Although Hawaii has always occupied a strategic military location for the United States Armed Forces, use military use of Kaho'olawe expanded greatly during the Second World War where pilots would often use the island as target practice for bombing runs.[10] Throughout much of the Cold War, the island would serve as a testing and training ground for weapons delivery systems, in addition to shore bombardment exercises.[10] One major effect of the routine bombing practice on the island of Kaho'olawe and its surrounding area is the creation of many craters in addition to the dangers of unexploded ordinance, which pose a threat to both people and wildlife.[10] Following extensive action and opposition to the military activities lead by the local Hawaiian population and stricter federal environmental protections in the United States, the United States Navy eventually ceased its operation on the island and returned the land back to civilian control.[10] As a result, a restoration project in Kaho'olawe was funded in order to clean up the leftover ordinance, revegetate bombed up areas, and control erosion.[10]

Conservation

Marine Conservation

Kuleana Coral

Kuleana Coral Restoration was founded in 2019, a non-profit organization dedicated to the restoration of degraded coral reefs around O’ahu.[11] The approach adopted by Kuleana Coral is a combination of indigenous knowledge and modern scientific practices, aligning with the concept of 'Āina Momona (the fertile or rich land)[12], with a vision of fostering abundant reef ecosystems.[11] Coral reefs worldwide are facing severe degradation, prompting global efforts to address these losses through affordable and scalable solutions.[11] Coral restoration has thus become a critical and evolving field, and Kuleana Coral actively engages in ongoing studies and collaborations with organizations developing successful restoration techniques, both locally and internationally.[11]

One of the primary challenges faced by reef restoration in Hawaii is the slow growth rate of Hawaiian corals.[11] In contrast to the average growth rates of 12-18 cm per year seen in Caribbean or Great Barrier Reef corals, Hawaiian corals exhibit a must slower growth rate, averaging only 2 cm per year.[11] The slow growth significantly extends the time required for Hawaiian corals to recover from losses.[11]

Kuleana Coral is focused on refining and optimizing coral restoration methods tailored for Hawaii.[11] The organization aims to develop techniques that can be applied broadly to support reef restoration efforts across the Hawaiian Islands.[11] The approach taken by Kuleana Coral involves utilizing existing coral colonies and maintaining the corals in their natural ocean environment throughout the restoration process.[11] This strategy helps avoid the risks, expenses, and time associated with establishing land-based nurseries.[11] By keeping the coral in the ocean, Kuleana Coral seeks to streamline the restoration process and make it more cost-effective.[11] The organization expresses hope that these streamlined and cost-effective methods can be scaled up to address reef damage on a larger scale throughout Hawaii.[11] As Kuleana Coral continues to refine its techniques, the focus is on reducing costs and developing systems that can be easily transported to different restoration areas.[11] The use of mature colonies with high survivability rates contributes to the immediate return of ecological services, adding to the efficiency of local, in-situ restoration methods for Hawaiian coral reefs.[11]

Mai Ko Po Mai - Indigenous Hawiian Marine Management Plan

The Mai Ka Pō Mai framework is a Native Hawaiian management framework for the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM).[13] The framework is designed to integrate both Native Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian components into a cohesive management plan.[13] The Collaborative Working Group (CWG) and co-managing agencies played a significant role in supporting and guiding the plan's development over several years.[13] Native Hawaiian elders, community members, OHA (Office of Hawaiian Affairs), and NOAA ONMS (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of National Marine Sanctuaries) staff supported the framework.[13]

The development process incorporated Kanaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) methodologies for over a decade, involving Native Hawaiians in management agencies and public community members.[13] These methodologies aimed to integrate Hawaiian knowledge and traditions, emphasizing the relational and holistic nature of Hawaiian knowledge.[13] The framework is based on Hawaiian cosmology and worldview, specifically derived from the Kumulipo.[13] It incorporates the realms of Pō (primordial darkness) and Ao (realm of light and the living).[13] The framework includes elements like Ke Alanui Polohiwa a Kāne (Tropic of Cancer) and Kūkulu o Kahiki (pillars of the ancestral homeland).[13] The framework identifies specific management domains represented by Hoʻokuʻi and the four Kūkulu, each with components such as purpose, guiding principles, and desired future outcomes. Action strategies, referred to as kuhikuhi, point out pathways for each component.[13]

The development process of the framework yielded lessons emphasizing the importance of recognizing Indigenous knowledge, incorporating diverse knowledge systems, allowing for iterative learning, and establishing a foundation for long-term commitment and capacity building.[13] Successful co-management with Indigenous peoples requires meaningful involvement and equitable engagement in planning processes. The Mai Ka Pō Mai framework exemplifies the importance of building relationships and trust between Indigenous communities and management agencies.

Terrestrial Conservation

THE ʻALALĀ PROJECT: RESTORING HAWAIʻI’S NATIVE CROW TO THE WILD

The conservation program for the ‘Alalā, or Hawaiian crow, is driven by a comprehensive rationale aimed at restoring the species to its native habitat while simultaneously addressing ecological and cultural needs.[14] The program recognizes the critical role of the ‘Alalā in the Hawaiian forest ecosystem, emphasizing the species' importance for seed dispersal and its cultural significance in Native Hawaiian traditions.[15] The strategies employed encompass a combination of captive breeding, habitat restoration, and meticulous release efforts.[15] Captive breeding addresses the decline in wild populations, with dedicated staff managing breeding activities and caring for the birds.[15] Concurrently, releases into the wild involve innovative approaches such as predator aversion training and consideration of the birds' personalities and group dynamics.[15] The program acknowledges the long-term commitment required for successful recovery, evident in the collaborative efforts of diverse partners.[15] While the success of the program is marked by some progress, such as successful avoidance of predation in certain releases, challenges persist, notably incompatibility among mating pairs and the intricacies of breeding in captivity.[15] Evaluating the program's success requires considering not only conservation outcomes but also the social impact, including cultural preservation and community engagement, elements critical for the program's holistic success.

References

Please use the Wikipedia reference style. Provide a citation for every sentence, statement, thought, or bit of data not your own, giving the author, year, AND page. For dictionary references for English-language terms, I strongly recommend you use the Oxford English Dictionary. You can reference foreign-language sources but please also provide translations into English in the reference list.

Note: Before writing your wiki article on the UBC Wiki, it may be helpful to review the tips in Wikipedia: Writing better articles.[16]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Englesbe, M. J., Brooks, L., Kubus, J., Luchtefeld, M., Lynch, J., Senagore, A., Eggenberger, J. C., Velanovich, V., & Campbell, D. A. (2010). A statewide assessment of surgical site infection following colectomy: The role of oral antibiotics. Annals of Surgery, 252(3), 154–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f244f8

- ↑ Mitchell, Christen; Ogura, Christine; Meadows, Dwayne; Kane, Austin; Strommer, Laurie; Fretz, Scott; Leonard, David; McClung, Andrew (October 1, 2005). "Hawaii's comprehensive wildlife conservation strategy". Department of Land and Natural Resources.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Harrington, Carrie L.; Keali'i Pang, Benton; Richardson, Mike; Machida, Susan (2020). Goldstein, Michael I.; DellaSala, Dominick A. (eds.). "Physical Geography of the Hawaiian Islands". Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes: 145–156 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Olson, David (2023). "Hawai'i Tropical Islands Bioregion". OneEarth.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sherwood, Alison R; Carlile, Amy L; Neumann, Jessica M; Kociolek, J Patrick; Johansen, Jeffrey R; Lowe, Rex L; Conklin, Kimberly Y; Presting, Gernot G (2014). "The Hawaiian freshwater algae biodiversity survey (2009-2014): systematic and biogeographic trends with an emphasis on macroalgae". BMC Ecology – via Open Access.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 McDowall, R. M. (2003). "Hawaiian biogeography and the islands' freshwater fish fauna". Journal of Biogeography – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Price, Jonathan P.; Wagner, Warren L. (2018). "Origins of the Hawaiian flora: Phylogenies and biogeography reveal patterns of long-distance dispersal". Journal of Systematics and Evolution – via Wiley.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Vitousek, P.M.; Ladefoged, T.N.; Kirch, P.V.; Hartshorn, A.S.; Graves, M.W.; Hotchkiss, S.C.; Tuljapurkar, S.; Chadwick, O.A. (11 June 2004). "Soils, Agriculture, and Society in Precontact Hawai`i". Science. 304: 1665–1667 – via ReasearchGate.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 MacLennan, Carol (2004). "The Mark of Sugar. Hawai'i's Eco-Industrial Heritage". Historical Social Research. 29: 37–62 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Blackford, Manse G. (2004). "Environmental justice, Native rights, tourism, and opposition to military control: The case of Kaho'olawe". The Journal of American History. 91.2: 544–574 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 Our story | kuleana coral reefs | non-profit coral reef restoration west oahu. (n.d.). Kuleana Coral Reefs. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://www.kuleanacoral.com/ourstory

- ↑ Native hawaiian organization | ‘āina momona | hawaii. (n.d.). Ainamomona. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://www.kaainamomona.org

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 Quiocho, K., Kikiloi, K., Kuoha, K., Miller, A., Wong, B. K., Pousima, H. K., Andrade, P., & Wilhelm, ʻAulani. (2023). Mai Ka Pō Mai: Applying Indigenous cosmology and worldview to empower and transform a management plan for Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Ecology and Society, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-14280-280321

- ↑ ʻalalā project. (n.d.). Retrieved December 4, 2023, from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/alalaproject

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 The ‘alalā project | u. S. Fish & wildlife service. (2023, October 16). https://www.fws.gov/project/alala-project

- ↑ En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Writing better articles. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Writing_better_articles [Accessed 18 Jan. 2018].

| This Tropical Ecology Resource was created by Course:GEOS303. |