Course:GEOS303/2022/Indonesia- Lindsey, Ingrid, Alexander, Aimee

This page will focus on the eastern side of Wallace’s Line in the Indo-Australian Archipelago.

Biogeography

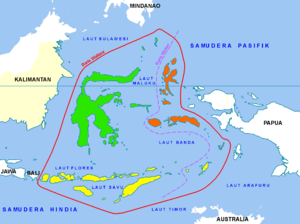

Boundaries: Wallacea is a fauna transitional zone referring to the area of oceanic islands located between the Asian Sunda Shelf and Australian Sahul Shelf. These are the continental shelves outlined by Wallace’s Line on its west and Lydekker’s Line on its east. Wallace’s Line illustrates the abrupt faunal discontinuities within these regions and the islands considered oceanic due to the lack of terrestrial connections to any surrounding land since its formation. The faunal discontinuities and limits of terrestrial taxa follow Sunda Shelf’s eastern edge which are attributed to geological processes such as tectonic movements.[1]

Bioregions: There are three main bioregions of Indonesia: the Sundaland bioregion, the Wallacea bioregion, and the New Guinea bioregion. We will be focusing on Wallacea bioregion in our project.[2]

Biomes: There are two main biomes in the Wallacea bioregion. The first biome is the Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests. This type of biome has a consistently high rainfall (must be greater than 200 cm/yr) and has a low variability in annual temperature. The Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests also have the highest rate of species diversity of any terrestrial biome, with about half of the world’s species living there. The main tree species here are Evergreens, Semi-Evergreens, and Deciduous trees. The other biome in the Wallacea bioregion is the Tropical and Subtropical Dry Broadleaf Forests. Similar to the moist broadleaf forests, this biome is characterized by warm temperatures year round, and hundreds of centimeters of rain per year. The biggest difference is that this biome has a long dry season, and not consistent rain like the biome above. There will be months at a time where there is no rainfall whatsoever. Biodiversity here is still quite high, but not comparable at all to their rainforest counterpart. Most trees here are deciduous, and lose their leaves annually.[3][4][5]

Ecoregions: There are nine main ecoregions in the Wallacea bioregion. They are as follows:

- Lesser sundas deciduous forests

- Banda seas islands moist deciduous forests

- Timor and wetar deciduous forests

- Sulawesi lowland rain forests

- Sulawesi montane rainforests

- Sumba deciduous forests

- Halmahera rain forests

- Seram rain forests

- Buru rain forests [6]

Geological Influences: This region of Wallacea comprises a series of different islands, all with unique and specific geological origins. The dominant origins of the islands on the eastern side of Wallacea include: continental crustal fragmentation and volcanism. The Wallacea area is framed by two different continental shelves that influence unique tectonic and geological conditions both terrestrially and aquatically.[7]

Marine Environments: There are several marine environments that are significant to acknowledge within the Indo-Australian Archipelago. These include:

- Coral Reefs (particularly fringe and barrier reefs)

- Seagrass beds

- Mangroves [7]

Diversity

Patterns of biodiversity: The Wallacea biodiversity hotspot is home to many species, as the tropical climate, insular biogeography, and unique geological past supports the highest levels of endemism in the world. Sulawesi Island, the largest island located in the northwest region of Wallacea, has among the highest number of terrestrial species, with many found nowhere else[8]. Approximately half of Wallace's land surface (~17.7 million hectare) is forest cover and supports these patterns of biodiversity. Evergreen and semi-evergreen forests cover the lowlands of the equatorial zone (Sulawesi and Maluku) and monsoon forest covers the most seasonal subregion in the Lesser Sundas. The biodiversity in this dryer subregion is significant, however is not comparable to their rainforest counterpart. Karst ecosystems in Sulawesi and Maluku also have great biological importance, where the unique isolated environment has driven speciation and evolution of specialized endemic fauna[9]. Most notably, terrestrial biodiversity in Wallacea is distinct from neighboring regions such as Borneo and Papua, with the overall striking and consistent pattern demarcated by Wallace’s and Lydekker’s Line[10].

How have biogeography and evolutionary history shaped local diversity?

There are several threats to the level of biodiversity that is observed in the eastern side of Wallacea. Habitat loss and fragmentation is becoming increasingly present and studies have begun to show that this is leading to declines in population and increased extinction rates[11]. There is research being done to investigate whether or not habitat fragmentation is resulting in reverse speciation. This phenomenon is observed when decreasing the overall area of suitable habitat for different species as well as decreasing the interconnections between these areas results in both the loss of species and the long term convergenging evolution of species. This is an extremely interesting dynamic to investigate in this area as much of the speciation that has occurred in this region is due to the impacts of vicariance.

The general cause for habitat loss in this region is land use changes. These changes are primarily due to deforestation that is often a results of the increase of permanent agriculture. This threat to biodiversity is augmented by the fact that a greater amount of research is required to better understand the extent of the impact this will have on biodiversity. The construction of better baselines is needed in particular for forest ecosystems[12].

Human influences and Threats

Ancient Humans and Wallacea

The Wallacea islands have been inhabited by humans for thousands and thousands of years, and therefore the environment has been constantly changing due to these migrations. Some of the first ancient humans during the Neolithic and Early Metal Ages were farmers and hunter-gatherers. These islands have been shaped by the migrating Austronesian farmers and indigenous hunter-gatherers from these ages, resulting in regional variations among islands. Northern islands show more Austronesian and papuan-related influences, while southern islands show more mainland southeast asian influences. Northern islands can have more farming methods, while southern islands showed more evidence of hunter-gatherers during this time period. [13]

Industrial logging

Much of the industrial logging activities in Indonesia are considered unsustainable, leading to severe degradation of forest and subsequent biodiversity loss. In addition to common selective logging of specific tree species that affects the resulting structure and composition, large- and small-scaled illegal logging can then lead to palm oil land-use once an area is no longer economically viable. In 2004, the Ministry of Forestry launched a restoration license to ensure conservation and sustainable logging practices. As of 2014, the Burung Indonesia is the only organization that has applied for such a license in Wallacea. Logging practices in Wallacea are weakly enforced in terms of how much tree volumes and areas can be logged, as a result of a lack of budget and staff training and incentive. Indonesian Timber Legality Standard has been made with the goal of independently verifying the enforcement of sustainable logging practices. However, this practice is primarily concerned with logging companies having the right legal documents, and less to do with ensuring sustainability practices. [9]

Small Scale and illegal logging

Illegal logging can be defined as being unplanned, unlicensed and unregulated. They can also occur on a large-scale, though this has reduced since 2005. A major issue with illegal logging is that this sort of activities often penetrate into abandoned logging concessions, containing undersize timber, that were meant to be left alone to grow. Moreover, illegal logging occurring in national parks contributes to the degradation of the forest and this land is often then converted in to agricultural or timber plantation forest land uses

Causes for illegal logging practices stem from insufficient and lack of enforcement and monitoring of these land areas on the part of local forestry agencies. Many local indigenous communities view the forested area as belonging to their communities, and subsequently resent licensing permits given to companies that allow them to log the area. In some instances, however, some communities allow these activities to take place and/or partake in them for economical means. Illegal logging activities will unavoidably continue to be a problem with an increase in population, which calls for stronger cooperation between forest agencies and communities on defining local rights over forests. [9]

Unsustainable small-scale fishing

Though not a new threat, common fishing-catching activities include the use of bombs and poison that are growing in intensity in terms of increasing demand through increase in population as well as fishermen being able to travel longer distances. One major consequence results in algae dominated systems where reefs were abundant as a result of destroyed reef and their biota, and their inability to recover after intense stressful activities. Destructive fishing represents the largest threat to reefs, and about 93% of Indonesian reefs are threatened (when sedimentation is combined). As a result of the bombings, many fish have not reached maturity, which severely affects its population dynamics. These practices are largely as a result of a lack of legally enforced protection or lack thereof. However, legal protection of certain areas implemented by local communities have proven successful in reducing or eliminating destructive fishing in some areas. [9]

Agriculture

The threat that agriculture poses to Wallacea’s natural environment is twofold. The first threat is associated with the forestry sector. Oftentimes forested plots of land are used for building oil palm and sugar cane plantations. The demand for these two products by global industry further drives deforestation and habitat loss. Yet, not all farms and plantations are industrial, but rather owned by small shareholders. As an example, Timor Leste (found in the southern region of Wallacea) is a nation with a large proportion of its population living rurally. Paired with a high growth rate of its population and the unlikeliness of widespread urbanization, the threat that small agriculture may pose to the environment is bound to increase. In the Indonesian part of Wallacea, approximately 30 million people are dependent on agriculture for their income.[14]

In coastal areas, shrimp farming continues to pose a threat to Mangrove ecosystems. Shrimp farming involves the process of creating pond dwelling areas that typically become nutrient depleted after a few years. Consequently, this creates a cycle of land use change in Mangrove systems whereby areas are used and exploited which leads to more expansion of shrimp farming.[7]

Mining and Fossil Fuels

Wallacea contains both volcanic and sedimentary mineral deposits that yield in a variety of precious metals and materials. The mining and fossil fuel industries pose a threat to the health and survival of Wallacea's forest ecosystems. In this way it is similar to the threats posed by logging and agriculture. In order for resource extraction companies to obtain mining licenses they must get approval from various district heads of office. Consequently, the mining and fossil fuel industries are a source of income for government officials (both in a legal sense as well as illegally). This conflict of interest poses troublesome implications to the prevalence of natural forests in the region.[7]

Conservation

Biodiversity, environmental change and land-use policy in Sulawesi and Maluku

Despite Wallacea being a hub of biodiversity, especially vertebrate diversity, there is an exploitation of land by businesses that is understudied and overlooked. Researchers from British and Indonesian universities have paired up in this conservation project to study land use and environmental changes in Wallacea. The two main researchers in this project are Dr. Matthew Struebig from the UK and Professor Jatna Supriatna from Indonesia. They will do this by looking at vertebrate responses, as well as bird and mammal fauna responses to changes in land cover. Their project area will be along the same route that Wallace has taken through Sulawesi and Maluku to study the changes from Wallace’s time to our present day. They found that around 10,000 km2 was deforested between 2000-2018 and that about 50,000 km2 is expected to be lost by 2050[15]. This is going to threaten a lot more species, and put many past the brink to extinction. This is going to have grave effects on the biodiversity in Wallacea.

Flying foxes conservation through community partnerships – Alliance for Tompotika Conservation (AlTo)

The two primary species of bats that AlTo focusses their conservation efforts on are the Sulawesi Flying Fox (Acerodon celebensis) and the Black Flying Fox (Pteropus alecto). These species are endemic to Wallacea and consequently their habitat in the Tompotika region is critically important. The key threat to their survival is commercial hunting. This conservation project relies on the partnership between AlTo and members of the Tangkuladi Island that have agreed on making the small island into a bat conservation area. This relationship was formalized in 2013 with the creation of an ongoing ‘conservation lease’ that AlTo purchased. In conjunction with the partnership, the organization runs local education programs. These programs focus on the vital role bats play in ensuring pollination in the tropical forest ecosystem through their consumption of various fruits. The use of protected areas based on community partnerships is an important bottom up approach. The main challenge this strategy faces is that if it is not matched with governmental level conservation efforts, the efficacy of the local protected area may be undermined. [16][17]

Value Added Processing Of Indonesian Farmed Seaweed - The Wallacea Trust

To combat one of the aforementioned threats, this localized framework developed by The Wallacea Trust aims to support value-added products from farmed seaweed in Indonesia. This conservation project provides a mechanism to encourage sustainable practices to improve agricultural yields, whilst bringing a greater share of profits to the local seaweed farmers. This project is effective, because seaweed farming can become an alternative income stream for fishermans, protecting coral reefs, aquatic habitats, and biodiversity from the pressures of over-fishing[18]. Hydrocolloids such as agar are derived from seaweed, which has many uses in food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. However, supply chain inequities give minimal compensation for farmers. This initiative aims to produce valuable carrageenan from Indonesian farmed seaweed at a local scale, to allow raw material to be sold at factory-gate prices (rather than farm-gate). The seaweed processing method has been successfully tested in laboratories, and now a small pilot plant is in the works. Their goal is to develop full-scale operation plants, working closely and fairly paying farmers for environmentally sourced raw materials[18]. By providing an alternative income stream and encouraging local fishers to surrender their fishing license, these outputs can support the local economy and provide long-term food security for Indonesia.

Burung Indonesia

Established in 2002, Burung Indonesia (meaning “Indonesian Birds”) is a national conservation agency at the forefront of preserving birds and their habitats across Indonesia, including those in Wallacea. There are 1,769 species of Birds (Burung Indonesia, 2017) found across the country, making Indonesia as having one of the most diverse bird species. Burung Indonesia’s overarching goal is to conserve all bird species and their habitats across the country. It outlines its goals in this three-part mission statement: (1) to preserve the diversity of Indonesian birds and their habitats; (2) Work together with the community to develop sustainable development; (3) to develop a sense of appreciation, understanding, care, and love for birds and their environment. Burung Indonesia encourages the management of natural production forest areas through ecosystem restoration. Conservation at the site level, sustainable management of productive landscapes, and restoration of natural productive forests. Burung Indonesia partners with the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, receives funding from the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety of the Federal Republic of Germany, KFW, along with funding from individuals alike. Burung Indonesia is also a member of the BirdLife International global partnership network. [19][20][21][22]

References

- ↑ Lohman D.; et al. (2011). [1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145001 "Biogeography of the Indo-Australian Archipelago"] Check

|url=value (help). Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics. 42. Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ↑ "List of ecoregions in Indonesia". Wikipedia.

- ↑ "Ecological Regions Of Indonesia". World Atlas.

- ↑ "TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL MOIST BROADLEAF FOREST". Ecology Pocket Guide. 2019.

- ↑ "TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL DRY BROADLEAF FOREST". Ecology Pocket Guide.

- ↑ "Wallacea Ecoregions" (PDF).

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Burung Indonesia (June 2014). "Wallacea Biodiversity Hotspot" (PDF). Critical Ecosystem.

- ↑ "Interim Report- The Study on Arterial Road Network Development Plan for Sulawesi Island and Feasibility Study on Priority Arterial Road Development for South Sulawesi Province" (PDF). June 2007. Retrieved 10/20/2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Wallacea Biodiversity Hotspot" (PDF). June 2014. Retrieved 10/20/2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Struebig, Matthew (19 October 2022). "Safeguarding Imperiled Biodiversity and Evolutionary Processes in the Wallacea Center of Endemism". Bioscience. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - ↑ "Forecasting biodiversity losses in Wallacea from ecological and evolutionary patterns and processes". UK Research and Innovation. Retrieved 10/20/2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Biodiversity, environmental change and land-use policy in Sulawesi and Maluku".

- ↑ Oliveira, Sandra; et al. (12/02/2022). "Ancient genomes from the last three millennia support multiple human dispersals into Wallacea". Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ "Wallacea–Threats". Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. 2022.

- ↑ "Biodiversity, environmental change and land-use policy in Sulawesi and Maluku".

- ↑ Ostrom, Elinor (12/02/2022). "Community-based conservation in a globalized world". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Alliance for Tompotika Conservation". 2021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 "VALUE ADDED PROCESSING OF INDONESIAN FARMED SEAWEED". The Wallacea Trust.

- ↑ "Burung Indonesia: Tentang Kami". Burung Indonesia. 12/02/2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Burung Indonesia: Sejarah". 12/02/2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Burung Indonesia: Visi Misi". 12/02/2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Burung Indonesia: Mitra". 12/02/2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

| This Tropical Ecology Resource was created by Course:GEOS303. |