Course:GEOG350/ST1/North End Winnipeg

Housing Decline in the North End

Introduction to the North End

Neighborhood Boundaries

The North End is a large district on the north side of Winnipeg. As a cultural hub in the city, the opinions on the boundaries of the district often vary from person to person. Colloquially, the North End may be used to refer to the neighborhoods immediately north of downtown Winnipeg and the West End, bordered by Inkster Blvd to the north, the Canadian Pacific (CP) rail yard to the south, McPhillips St to the west, and the Red River to the east. For the purpose of this analysis, the focus will be on the areas north of downtown only, as this has traditionally be the area most plagued by poor housing conditions and its associated social issues. This area is bordered by Arlington St to the west, Redwood Ave to the north and shares the same south and east borders. This section of the North End is composed of 4 neighborhoods – William Whyte, Dufferin, Lord Selkirk Park and Point Douglas.[1]

History

The North End was first built at the end of the 19th century to accommodate the influx of Eastern European immigrants coming to the city. Most of these immigrants worked in the large rail yards that form the southern border of the neighborhood and their associated industries. The area developed rapidly because of the booming railway industry and quickly became known locally as the “foreign quarter” of the city, physically isolated by the rail yards but also socially isolated by racist attitudes from other Winnipeg residents.[2]

Despite the fact that most residents were employed, most North End residents also lived in poverty and in poor housing conditions. Even when it was first built, housing in the North End was largely inadequate. Lots were too small for the structures on them and houses were poorly constructed, extremely overcrowded and lacked water supply. This led to poor living standards, especially wide spread disease, in the North End.

Not all was negative in the North End; out of the community’s physical and social isolation, a vibrant culture was born. Selkirk Ave became a blooming commercial strip, mainly filled with Eastern European shops and stores. Neighborhood newspapers were made in a variety of languages. Although the neighborhood residents lacked political power, the neighborhood was known for its political activism, particularly in the area of labour politics where many of its residents were a part of the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

In the years after World War II, the North End went through significant changes. Winnipeg, like many other North American cities, began a major shift in development towards suburbanization. Many of the North End residents that had the financial ability to do so left the North End for bigger and newer homes in the suburbs and many of the community’s businesses and cultural organizations followed. At the same time, the manufacturing jobs largely held by North End residents began to leave. This heavily damaged the neighborhood’s economic and cultural life. Around the same time, the Aboriginal population in Canada began to urbanize, particularly in Winnipeg. Many moved to the North End, attracted by the cheap rental housing. Today, Aboriginal people make up nearly half of the North End.

Like their Eastern Europeans predecessors, Aboriginals in the North End were faced with similar conditions: social and spatial segregation, racism, poverty and poor housing conditions. However, in many aspects, conditions in the North End have become worse. Most of the industrial jobs that were once the main source of employment for the Eastern European immigrants are now gone. Winnipeg’s inner city, including the North End, has been plagued by street crime and drug abuse, which has only further intensified the neighborhood’s poverty. The housing stock is the oldest in the city and also in the greatest need of repair. Many of the neighborhood’s properties are owned by slum lords who have purposely allowed properties to decay because it is not worth the investment.[3]

Demographics

| Population[1] | North End | Winnipeg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % Change | Number | % Change | |

| 2006 | 12,255 | 8.0% | 633,451 | 2.2% |

| 2001 | 11,350 | -11.0% | 619,544 | 0.2% |

| 1996 | 12,755 | -8.0% | 618,477 | 0.5% |

| 1991 | 13,865 | -4.3% | 615,215 | 3.5% |

| 1986 | 14,470 | 2.7% | 594,555 | 5.3% |

| 1981 | 14,090 | -15.9% | 564,475 | 0.6% |

| 1976 | 16,745 | -16.5% | 560,875 | 4.8% |

| 1971 | 20,055 | 535,100 |

In 2006, the North End was home to roughly 12,000 residents. However, this is far less than the 20,000 people who lived in the North End in 1971, a 40% decrease. Every census since 1971 has shown a decrease in population in the North End except in 1986. This is in contrast to the city as a whole, which has seen slow but positive growth in each census since 1971, totaling an 18% growth from 1971 – 2006.[1]

Of those living in the North End, 45% identify as Aboriginal. Another 11% identify themselves as Filipino and 6% as some other visible minority. Even within the North End, distributions of visible minorities and Aboriginals are uneven; in Lord Selkirk Park, 67% of the population identifies as Aboriginal. In Winnipeg as a whole, 10% of residents identify as Aboriginal, 6% identify as Filipino and 10% identify as some other visible minority.[1]

The North End has traditionally been characterized by high rates of poverty.[3] The median household income in the North End in 2005 was $22,934, more than 50% less than the citywide median household income of $49,790. After taxes, in 2005, 51% of North End residents lived below the poverty line as calculated by Statistics Canada, including a staggering 81% of children under the age of 6. This is in sharp contrast to the 16% of Winnipeg residents and 26% of Winnipeg children that live in poverty. As with many other lower income and inner city communities, housing occupancy in the North End is largely rental based. 65% of North End residents live in rental housing. Citywide, 35% of Winnipeggers live in rental housing.[1]

The Importance of Adequate Housing

The Issue of Poor Housing

The housing system is important to study because housing ultimately plays a critical role in everyone’s lives. In Canada, housing is the single largest occupant of space in cities, thus making it a priority to study [4]. Dowell Myers points to housing as being at the centre of everything; “ It is physical design, it is community economic development, it is social development, it is important to health and educational outcomes, it can be a poverty reduction tool, and it is an investment, a wealth creator and a generator of economic development. It is both an individual and public good”[5]. That being said, if housing is inadequate, in disrepair or unaffordable it is inevitable that instability will follow.

Analyzing

Housing is an issue that must be addressed, specifically in the North End as the housing stock here, as well as its population have long been neglected. The housing stock in this neighbourhood should be closely analyzed because of the central role it plays in mental health, educational outcomes and economic opportunity. Housing becomes a problem when “citizens are required to spend increasing proportions of available resources on maintaining a roof over their head, the resources available to support social determinants of health such as food and educational resources are diminished”[6]. As housing remains homeowners largest monthly expense, efforts should be made to minimize some of the stress associated with this issue.

Resolving

“In economically depressed neighbourhoods, improving access to affordable, good-quality housing can boost the health, quality of life, and future prospects of local residents. It can also stimulate community economic development and physical as well as social neighbourhood renewal”[7]. In the North End, low income individuals and minorities have encounter negative neighbourhood effects including poverty and crime. As housing deteriorates, it discourages investment in the area and creates flight from the neighbourhood[8]. Revitalizing a community affected by a poor housing stock can help improve the neighbourhood, from a social and an economic perspective.

Individuals Affected

Housing issues affects numerous types of people. Low-income residents may become displaced or homeless when the quality and availability of housing diminishes. High-income residents with high standards of living may decide to move away from a neighbourhood as they are looking to avoid living in close proximity to poor housing communities ridden with crime and poverty. Upper-class residents often choose to live in safe residential areas alongside neighbours expecting the same standards and this often leaves the poor and homeless displaced. Social housing issues also affect real-estate companies, investors and the municipal government. Real estate companies look to buy land, develop it and sell at higher prices in order benefit economically. The municipal government aims to provide social housing to low-income residents, develop deteriorated neighbourhoods and reduce crime and poverty within the city.

Housing Conditions in the North End

Characteristics of Built Form and Current Housing Conditions

The North End is separated from downtown Winnipeg by the CP rail yard, which acts as huge physical barrier between the two areas. While once a major source of employment in the area,[3] the rail yard is now well under capacity and seen as an eyesore, particularly because of its location in the heart of the city.[9] Access to the North End from the south is restricted to bridges over the rail yard on Arlington and Salter St and an underpass on Main St. The result has left the North End spatially segregated from the city;[9] walking into or out of the neighborhood is long and difficult and access is largely dependent on motor vehicles, something many North End residents do not have access to.[1] Access to nearby places in downtown is often too far away because they are blocked off by the rail yard. This spatial segregation has compounded further to both a social and cultural isolation from the rest of the city, which creates an image of the North End being “on the wrong side of the tracks” both literally and figuratively.[9]

The housing stock of the North End is notable for being the oldest in the Winnipeg, but also the most physically deteriorated. Roughly half of housing in the North End predates the end of World War II, as compared to 20% of houses citywide, making it the among the oldest in the city.[1] Despite the historical significance of the North End’s housing stock, the neighborhood is in major decline. In 2006, 17% of occupied houses in the area were in need of major repairs, the highest in the city, versus only 8% in Winnipeg as a whole.[1] On top of this, many more properties remain derelict. In 2010, there were 614 such buildings in the city, the majority of which were found in the North End and West End neighborhoods. However, Winnipeg has created several by-laws in an attempt to reduce this number, with the goal of reducing this number to 300 by the end 2013.[10]

Underlying Causes of Deterioration

Market-Driven Process of Decline

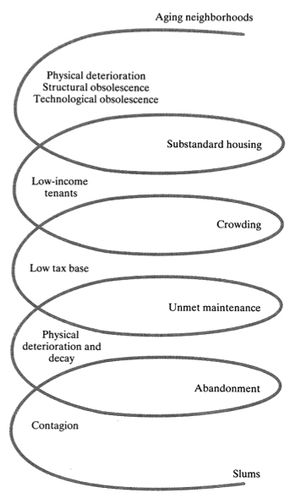

Winnipeg is one of many cities to fall into a spiral of inner city decay. Across North America, a fairly well established process of inner city decline has been recognized.[11] It is important to understand that decline is initially driven by housing markets because it is this idea that forms the basis for the process of inner city decline. This process generally affects the oldest housing stock in a city first. As inner city houses age and deteriorate residents with the economic means to do so begin to move to newer suburban houses on the city’s outer edge, often attracted by newer, larger houses and lots. The housing that remains occupied in the inner city becomes substandard. As a result, older housing in the city filters down to lower income individuals and families.[12]

Because the filtering down process concentrates poverty in these neighborhoods, the social stresses that come with poverty are further concentrated and only act to further intensify the effects of poverty. Some of these stresses can include crime, substance abuse and poor educational outcomes. Lower income families may also overcrowd houses so that they can be afforded, adding to the substandard conditions.[11]

The process also shifts the housing tenure in these neighborhoods from owner-based to rental-based because low-income families and individuals have less financial capabilities for home ownership. Since maintenance requirements increase with the age of housing despite declining rents and the fact that repairs and maintenance are generally done based on their ability to generate new income, older rental housing often remain neglected until they deteriorate to the point that major maintenance is no longer financially justifiable. This makes an easy target for slumlords, who often rent out said properties for as much profit as they can make, allow it to deteriorate until it is unviable to live in and leave the property vacant. Deteriorating housing affects not only those living in it, but also the surrounding community by lowering housing prices in the neighborhood. This, in turn, discourages major repairs, maintenance and other investments for all homeowners in the area because of depreciating sale values. This means that the deterioration of only a few properties in a neighborhood can create external costs on all properties in the neighborhood.[12]

Declining property values ultimately lead to a declining property tax base. With less economic capabilities, declining communities are put under financial strain to provide services and amenities to its residents. This lack of investment in the community only adds to the community’s further physical deterioration, lowered property values and flight from the inner city. Since it is the flight from these communities that creates the social issues in the first place, the process of inner city decline is cyclical, building upon itself over time.[12]

As residents continued to flee from the North End, the economy shifted from the Welfare State to the Neo-Liberal city. This meant that there would be little government intervention and the housing market would be driven by market forces. Unfortunately, with its current housing stock, the North End is unable to generate effective market demand. “These households generate a social need for housing rather than a market demand for it. A housing system based on the market mechanism cannot respond to social need.”[13]

The North End is a prime example of neglect on the behalf of the government. Only 5% of Canada's total housing accounts for Social housing, this is the second lowest (aside from the United States) in the Western World. Government support is allocated to existing home ownership and has “helped exacerbate problems in the rental-housing sector.”[14] By allowing market forces to take over the progress of the real estate industry, neighbourhoods such as the North End, will remain in a state of deterioration.

Winnipeg Perspective

Winnipeg fits well as an example of this process of inner city decline. This process has already been noted in the history of Winnipeg’s – and more specifically the North End’s – development.[3] Because of the age of North End’s housing stock, it serves as one of the areas of the city most vulnerable to this process of decline.[15]

Though one does not necessarily imply the other, the process of inner city of decline is inherently tied to the process of middle and upper class suburbanization because the flight from the inner city to suburban neighborhoods is part of the cause of inner city decline. This form of suburbanization has come to characterize Winnipeg’s development since its incorporation in 1873.[16] Because of Winnipeg’s historical slow growth, city officials have generally taken pro-development positions, in a desire to grow no matter the cost, and have accepted developer proposals despite their often inappropriate location, density, land use or strain on infrastructure and services.[17] The result is an very suburban city landscape marked by heavy debt to compensate for poor infrastructure choices.[12] Out of date zoning regulations in many of Winnipeg’s suburbs mandate specific housing specifications, lot sizes and minimum housing costs, originally intended to maintain affluent suburbs. These regulations must still be followed today, further proliferating the stratification of Winnipeg’s suburbs.[16]

The Winnipeg municipal government requires developers wanting to create new developments to submit a Financial Impact Analysis (FIA) to estimate the capital cost of development on the part of the city versus the potential revenue generated by the development. As recent as 1998,[12] the capital costs that expected to be accounted for in such analyses include street expansion, water and sewer mains and new parks. However, many relatively standard city services and amenities are not accounted for in this analysis, such as new schools and libraries, fire and police stations and recreational facilities. This results in suburban developments being approved, based on financial viability, despite not generating any revenue.[18] This indirectly subsidizes the cost of suburban developments relative to renovation or infill development by placing the extra financial burden not on the developers but on the city and ultimately, on taxpayers. Therefore, it is the city’s own public policy that inherently subsidizes outward growth in the city and the desertion of the inner city.[12]

Impact on Quality of Life

Housing decline not only affects community residents through the quality of life in their homes but also by affecting the community at large. As housing declines, this process affects aspects of the neighborhood besides housing which play a role in the quality of life in the area. Below are some of the ways in which the quality of life in the neighborhood has been affected by housing decline.

Local Business and Banking

Once home to a thriving local business community centered on Selkirk Ave,[3] the North End is now faced with businesses and major banking institutions fleeing the area while fringe banking services, such as pawnshops, cheque-cashing, payday loan and rent-to-own firms, have filled the void of financial services. Selkirk Ave, once a vibrant commercial corridor, has a commercial vacancy rate of 40% and has physically deteriorated significantly, deterring businesses from relocating to the North End.[8] There is currently one credit union, no major banks and one major bank ATM in the North End. If the borders of the neighborhood are extended out to McPhillips and Inkster (see Neighborhood Boundaries), there are three banks and two credit unions. This is an massive decline from the 15 major banks in the North End in 1997 and 20 banks in 1980. In place of these banks are fringe banking services, financial companies that offer short-term, extremely high-interest instant loans. The growth of the fringe banking sector began to appear in the North End as major banking institutions left the community, filling the financial service void. While they provide the convenience of instant cash on cheques and credit to those who may not otherwise have access, fringe banks are extremely costly on an annual interest basis compared to mainstream banks. In 1980, there was one fringe banking service, a pawnshop, in the North End; by 2002, there were 19. Ironically, two such locations are at Selkirk Ave and Salter St, the heart of the North End and the former site of two major banks.[19]

Education

As mentioned, the population of the North End has declined by 40% from 1971-2006.[1] The population that has remained is largely unskilled and uneducated. Just over 50% of North End adult residents have no form of educational certification (high school diploma or equivalent, trades certificate, apprenticeship, college diploma or university degree), the highest number in the city and far greater than the citywide rate of 23%. Another 24% of North End residents have a high school diploma or equivalent as their highest educational certification. North End residents are twice less likely to have some form of post-secondary education or training and four times less likely to have a university degree than others in Winnipeg.[1]

Access to Produce

Like many inner city communities in Winnipeg and across North America, the North End has become a food desert – there is a lack of access to produce and other fresh foods in the neighborhood. There is one grocery store in the North End and within the extended borders, there are three grocery stores. The community is largely served by corner store grocers, which are quite abundant. While the business is welcomed, these corner store grocers are not able to properly provide fresh foods to the neighborhood.[20]

Renewal in the North End

While the process of decline may be relatively well understood, the causes are not the same or universal to all cities.[21] No two cities are the same and therefore, responses to decline must be considered on a city-by-city basis. In the case of Winnipeg, a large influx of marginalized populations, many of which are Aboriginal, in the post-war era has played a large part in decline in the North End (see History section). This is certainly something that must be considered in the city’s approach to improving housing and neighborhood conditions in the area. However, housing is fundamental to the process of decline as it is the driving force for investment or disinvestment[2] and its improvement must be at the heart of the solution. It is also understood that decline cannot be attributed to any one single factor alone[21] and therefore the solution must be similarly multifaceted.

Public Investment

Housing plays a pivotal role in neighborhood decline; the deterioration of housing stock in a neighborhood can drive decline and ultimately create spatial concentrations of poverty because the process is market driven and provides a disincentive for investment.[12] Therefore, the reintroduction of quality affordable housing outside of the market is critical to reversing the process. Such a response may draw skepticism in Winnipeg because the city has previously made significant public investment in revitalizing its inner city, with little success.[18] However, they have failed not because of the nature of public investment, but rather because of how such investments were made. The final goal of any public investment in housing must not simply be to provide quality affordable housing, but more importantly to act as a catalyst for future development by improving property values in the surrounding areas.[2] Just as a few deteriorating properties can have a negative impact on neighboring properties and their market perceptions, a few quality properties in an area can help improve market perceptions on the area.

For such investments to be successful, Winnipeg must reevaluate its strategy of investment in affordable housing. Firstly, it must be a large scale investment.[8] While helping provide a few affordable houses, as many charitable organizations do, is positive, it is not an effective strategy from a public investment point of view because it will not fulfill its main purpose; that is, it cannot significantly affect the neighborhood housing market and catalyze greater investment on a small scale. The local and provincial government have shown a previous willingness to provide significant investments[12] but have not been successful. This is largely due to the distribution of investments. For an investment to best stimulate the housing market, they must be clustered together, rather than scattered across a large area.[2] Winnipeg’s inner city is a large geographic area of which the North End is only a small part and as such, scattering affordable housing across it will not affect its entire housing market. Instead, investments must be concentrated in small areas, such as a neighborhood or an even smaller area, like a specific block. This way, investments can have a significant impact on a small area that ideally, will impact its neighbors and eventually impact a whole community. Much like how decline creates a cycle of disinvestment, reinvestment in quality affordable housing has the potential to create a cycle of reinvestment by market builders and buyers.[2]

While public investment in a significant part in revitalization, it is also important to note that it cannot be the only part. As stated, decline is multifaceted and its reversal must be as well. Decline, though created by deteriorated housing, is greater than just housing. The process creates social stresses that must be dealt with.[21]

Building Social Capital

Currently North End Winnipeg is a neighbourhood low on social capital. Social Capital is characterized by social networks, mutual trust, and shared norms but more importantly it is a "social structure that facilitates action[22][23]." In the North End, residents are not necessarily familiar with their neighbours which has lead to a relatively isolated community. This sense of distrust in the community is connected to the high crime rates and deteriorating housing stock in the area. By building upon social capital, the neighbourhood can begin to rebuild trust, and advocate to community groups to help solve local issues specifically related to aboriginal youth and single parent families and their related housing problems.

Creating a stronger sense of community will hopefully ignite a cycle of investment in the neighbourhood. The North End Housing Project (NEHP) has jump started the initiative through focusing on promoting social capital on three levels; private, parochial, and public[24]. The goal of social capital is to increase home ownership which in turn will increase investment, encourage property maintenance, provide local employment, discourage migration form the neighbourhood and create a real community where neighbours can interact safely and be a participant in their community. The idea is when a community member owns a home, this reduces their mobility and become 10% more likely to know their neighbour[25].

However it is difficult to become an active member in the community when “fear of crime can cause families to disengage from community activities and become socially isolated. Makes it difficult to coach hockey teams, organize block parties or be on parent council.[26]” Jane Jacobs theory that social networks bring about prosperity may help to revitalize the North End into a vibrant neighbourhood. With “eyes on the street” and a larger social network, North End residents may be more inclined to step up informal social control. It has been seen that local friendships decrease the victimization by street robbery and stranger violence[27].

Through a grassroots initiative like the NEHP, increased home ownership is possible. This increases the stability of a neighbourhood, will improve the local housing market and will drive down crime rates in the surrounding area. Through social networks the problems of the local community can be heard and gentrification can be avoided.

Aboriginal Community in the Renewal Process

With 45% of the North End’s residents and 67% of Lord Selkirk Park’s population being identified as Aboriginal, the Aboriginal community and the ongoing effects of the colonization of Aboriginal people must be considered in Winnipeg’s approach to improving conditions in the North End. The renewal process must also take place on a smaller scale and help out Aboriginals, especially Aboriginal children as they have often internalized false assumptions about Aboriginal inferiority and shame[1]. Confidence needs to be instilled in Aboriginal children growing up and teach them that living in poverty in the North End of Winnipeg is not the only option. Measures through community organizations need to be taken to promote development in the people as well as the structural housing and building aspect. Social workers and community-based organizations promoting the prevention and awareness of poverty, racism, violence against women, gangs, drugs and addictions are important steps to take in helping people feel as though they have better options and opportunities in life and they are not hopelessly trapped in their situations. Aboriginal residents of the North End need to be encouraged and become engaged in building solutions to their problems for successful intense community development and community organizing. An increase in social workers and long-term economic funding of community-based organizations is needed to build closer a closer relationship with the Aboriginal community. These projects must be strong and long-term and include aboriginal female leaders in the community to motivate aboriginal girls growing up to prevent a sense of abandonment or lack of stability in their lives. The government as a primary funder must commit to funding and supporting community-based organizations over the long term for sustainability and consistency in the renewal process rather than abandoning development, which could give Aboriginals in the North End a sense of hopelessness.

Renewal in Action: The North End Housing Project

The North End Housing Project (NEHP) is an extensive community revitalization program in the North End that helps build and renovate affordable housing. It was originally started in 1999 as a new method of dealing with neighborhood decline after previous significant investments had failed.[28] The NEHP’s goal was straightforward: to provide adequate and suitable affordable housing to low income residents in the North End.[2] The concept of neighborhood decline being driven by the housing market was critical to the NEHP’s philosophy. Since NEHP understood that that there was a cycle of disinvestment in the North End, NEHP also attempted to impact the housing market, specifically in William Whyte, by creating a critical mass of quality affordable housing.[28]

As of 2005, NEHP had renovated 73 properties and built 20 infill units.[2] The infill properties were sold under market value and the renovated properties were sold to residents on a rent-to-own basis. To complete the work, roughly 20 people were hired by the NEHP. Those hired were all local residents, many of whom were on income assistance prior to, who were trained for the job. They were hired to work on not only NEHP projects but also on work from two other community groups and from commercial clients.[28]

The question that must be asked about the NEHP is was the project a success. One way of evaluating is by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s definitions of adequacy, suitability and affordability in housing.[21] A house is deemed inadequate if it does not have a bathroom or is in need of major repairs, unsuitable if does not meet occupancy standards (defined by one bedroom per adult couple or unattached adult and one bedroom per pair of sex-sex children) and unaffordable if housing payments are greater than 30% of the family’s gross income. Based on these parameters, NEHP was able to provide suitable and adequate housing to nearly all its residents and affordable housing to roughly 80% of its residents, with an average family paying 21% of its income to housing. However, it should be noted that the 20% who paid more than 30% of their income to housing were mainly welfare recipients, who paid more than 30% of their income based on current benefit system.[2] The impact on the housing market is harder to quantify because of a lack of clear data to analyze. Based on statistics from the Winnipeg Real Estate Board, housing prices in the North End increased by 11% in 2000, 5% in 2001 and 17% in 2002, as compared to a citywide rate of 1.1%, 6.4% and 3.8% respectively and statistical tests show that the change in the North End was statistically significant from the citywide changes.[28] However, despite positive movement, the neighborhood is still faced with many of the same issues of adequate affordable housing. One of the biggest roadblocks to further success is a lack of funding for the project.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 2006 Census Data, City of Winnipeg (Retrieved 21 June 2013)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Deane, Lawrence. 2006. Under One Roof: Community Economic Development in Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Fernwood Publishing.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Silver, Jim. 2010. Winnipeg's north end. Canadian Dimension. Jan, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/204141003?accountid=14656

- ↑ Bunting, Trudi E., Pierre Filion, and Ryan Christopher Walker. Canadian cities in transition: new directions in the twenty-first century. 4thd ed. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2010, 342.

- ↑ Bunting, Trudi E., Pierre Filion, and Ryan Christopher Walker. Canadian cities in transition: new directions in the twenty-first century. 4thd ed. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2010, 347.

- ↑ Bryant, Toba. The Current State of Housing as a Social Determinant of Health. Montreal: Policy Options Politiques, 2003, 55.

- ↑ Bunting, Trudi E., Pierre Filion, and Ryan Christopher Walker. Canadian cities in transition: new directions in the twenty-first century. 4thd ed. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2010, 351.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Reimer, Brendan. 2005. CED-Oriented Business Development Strategies for Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Manitoba Research Alliance. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ced" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mary Welch, North Enders have their say, Winnipeg Free Press, 2012-07-23 (Retrieved 21 June 2013)

- ↑ Bartley Kives, gathers new weapons against derelict buildings , Winnipeg Free Press, 2012-07-23 (Retrieved 21 June 2013)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lynch, Nicholas. "Governing the city." Geography 350 - 2013 Summer Session. University of British Columbia.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Deane, Lawrence. 2004. Community economic development in winnipeg's north end: Social, cultural, economic and policy aspects of a housing intervention. Ph.D. diss., The University of Manitoba (Canada), http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/305095513?accountid=14656

- ↑ Hulchanski, J. David. Canada's Dual Housing Policy: Assisting Owners, Neglecting Renters. Centre of Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto, 2007, 1.

- ↑ Hulchanski, J. David. Canada's Dual Housing Policy: Assisting Owners, Neglecting Renters. Centre of Urban and Community Studies, University of Toronto, 2007, 3.

- ↑ North End Community Renewal Corporation. 2001 William Whyte Neighborhood Housing Plan. Winnipeg: William Whyte Residents Association

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Fenton, Robert and Lyon, Deborah. 1984 The Development of Downtown Winnipeg: Historical Perspectives on Decline in Revitalization. Winnipeg: Institute of Urban Studies

- ↑ Donald, Betsy and Hall, Heather. Canadian cities in transition: new directions in the twenty-first century. 4thd ed. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2010, 284

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Institute of Urban Studies. 1991 "The Urban Limit Lines: Some Issues" in Workshop Proceedings: Urban Limit Line (1990). Winnipeg: Institute of Urban Studies

- ↑ Buckland, Jerry and Thibeault Martin. 2005. Fringe Banking in Winnipeg's North End. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- ↑ North end Assessment Report, Food Matters Manitoba, 2010-04-30 (Retrieved 21 June 2013)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. 2001. Disinvestment and the decline of urban neighborhoods. Ottawa: Cmhc, 90.

- ↑ Deane, Lawrence. 2006. Under One Roof: Community Economic Development in Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Fernwood Publishing.

- ↑ Lesser, Eric. Knowledge and Social Capital. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

- ↑ Deane, Lawrence. 2006. Under One Roof: Community Economic Development in Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Fernwood Publishing.

- ↑ DiPasquale, Denise , and Edward Glaeser. "Incentives and Social Capital: Are Homeowners Better Citizens?."Journal of Urban Economics 45, no. 2 (1999): 354-384.

- ↑ Deane, Lawrence. 2006. Under One Roof: Community Economic Development in Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Fernwood Publishing.

- ↑ Deane, Lawrence. 2006. Under One Roof: Community Economic Development in Winnipeg's North End. Winnipeg, MB, CAN: Fernwood Publishing.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Deane, Lawrence. 2003. North end housing project: A comprehensive approach to neighbourhood renewal. Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale(52): 123-127

Group Members

Rachel Greene, Matthew Asaminew and Chad Shaule