Course:GEOG350/2012WT1/Kitsilano Density

Kitsilano: Increased Residential Density and its Implications on the Urban Living Environment

Introduction

Kitsilano is situated along the coast of English Bay between Granville Island and Point Grey. It is bordered by Alma Street to the west, Burrard Street to the east, and 16th Avenue to the south, and encompasses the retail areas of West 4th Avenue and West Broadway ("Kitsilano").

Since 2006, Vancouver's population has been steadily increasing, experiencing a growth of 4.4% between 2006-2011. One popular area in particular has been Kitsilano. As mentioned in the article Clarifying and Re-conceptualising Density, increased density has mostly been desired on behalf of policy-makers for its sustainability advantages. However, increased density also creates other neighborhood problems such as cramped living environments which sacrifice the quality of living. Cramped living environments cause mobility, land use, economic, and social/psychological disadvantages such as loss of privacy, anxiety, and parking problems (Boyko and Cooper 10).

While residential densification in Kitsilano is a largely unavoidable and in some regards desirable process, some negative impacts on higer density on the neighborhood include: nominal distance between houses, streets overcrowded with parked cars resulting in narrow driving spaces, laneway homes causing more cramped environment, and escalating housing prices. In this project, we will discuss solutions to these issues such as: mid-rise mixed-use buildings on arterial streets (Condon 99); and the development of of new communities in outlying areas to encourage settlement in places other than Kitsilano and other high-density areas (Douglas).

Neighbourhood History

Similar to most areas in North America, the Kitsilano neighborhood was initially inhabited by Native Americans, a tribe known as the Squamish. The name Kitsilano for which the neighborhood is named is derived from the Squamish tribe chief August Jack Khatsahlano.

The first non-native settler, Sam Greer, arrived to the area with his family in 1862, to settle on a 65 hectare farm. However, he was placed in jail after hampering CPR railway construction following his land claim being revoked by the CPR. The farm was razed to the ground, and Greer passed away in 1925. Greer Street in Kitsilano is named after this early settler (Chandler).

The Kitsilano neighborhood began its residential development at the end of the 19th century at this point still referred to as “Greer’s Beach” because of Sam Greer’s early settlement, the city’s streetcar lines expanded into Arbutus and Cornwall. This streetcar “loop” made it easy for residents to access the downtown peninsula,the central location of the growing city. Further advancements in railway lines made Kitsilano increasingly attractive, putting the neighborhood in easy range of downtown ("History of Kitsilano"). While the area was gaining residents because of easy transportation to downtown, it was also garnering a reputation among the elite, hosting annual championship events at the Vancouver Lawn Tennis Club which attracted nationally recognized players.

Known as one of Canada’s best beaches, late 19th century Vancouver residents would trek via foot or water to camp at Kitsilano Beach, still known as Greer’s Beach. In order to open up the area to prospective residents, the CPR allowed B.C.Electric Railway to start a streetcar servicing Kitsilano. Vancouver’s residential history closely follows the streetcar lines, because they provided quick and easy access to downtown, and Kitsilano remained true to this precedence ("Greer's Beach").

Contributing to Kitsilano's development as an elite residential neighborhood was the first settler’s daughter, Jessie Hall. Married to Vancouver’s first notary public, they built a mansion known as Killarney Manor, which became the social center of Kitsilano ("History of Kitsilano").

Killarney Manor is where Jessie Hill conducted most of her anthropological work, on the corner of Bayswater and Point Gray Road. It is presently the site of condominium buildings, but the original stone wall still remains.

Although Kitsilano appealed to the upper classes, it also appealed to regular working class families because of its proximity to downtown, and the ease of getting there provided by the streetcar service. A second streetcar line was opened in 1909, running from Granville Bridge and connecting 4th Avenue to Alma, making the area even more accessible. The expansion of Kitsilano as a prime residential location came after this streetcar line opened, and blocks of two and two-and-a-half story wooden craftsman-style houses were erected between 4th and Broadway (Condon). The western end of Kitsilano remained more exclusive and upper-class, while the Eastern end, because of its proximity to industry, appealed more to working class residents.

During World War 2, many of the homes were converted into rooming houses and stayed that way after the war ended -an appealing prospect for many university students. In the decades following World War 2, Vancouver went through the process of deindustrialization; as industry declined, economic restructuring followed, and industry was relocated to cheaper and more modern sites, leaving the Vancouver waterfront unrecognizable (Bourne and Ley 21). As proximity to work no longer made Kitsilano appealing to the working class, and the area experienced a decline in demand and housing prices.

After deindustrialization and the rise of suburbs had made Kitsilano a declining and inexpensive neighborhood to live in, the area attracted many hippies from across Canada and the United States ("Kitsilano History & Heritage"). Previously a subculture, as the hippie movement gained popularity it attracted more mainstream appeal; therefore, yuppies attempting to model their lifestyles to those of hippies flooded into Kitsilano. These yuppies were higher-class residents who used their money to imitate the hippie lifestyle, and began the transformation of the area from a declining neighborhood into a stable neighborhood.

Starting in the 1970's, the Vancouver waterfront experienced a transformation from industrial and railway use to residential and recreational use (Bain 267-268). This caused the downtown area to regain its appeal. In the years this transformation, Kitsilano began to regain its appeal to middle and upper-class residents because of its close proximity to the revitalized downtown, and enviable views of parks and beaches. As Figure 1 shows, Kitsilano was in the top quintile for gentrification in Vancouver (Ley and Dobson 9-10); this led to the area becoming gentrified, as many who moved into the area were newly wealthy from downtown jobs, who restored houses to regain their charm. The nighborhood experienced revitalization and redevelopment, which has resulted in Kitsilano becoming a wealthy area with a younger population, and an increasing demand for housing.

Figure 1 "the Map of Gentrification in the City of Vancouver, 1971-2001."(Ley and Dobson 10)

Figure 1 "the Map of Gentrification in the City of Vancouver, 1971-2001."(Ley and Dobson 10)

Demographics

Neighbourhood Demographics:

The majority of Kitsilano residents are single, with post-secondary education. They are primarily tenants, living in an area comprised mainly of apartment buildings, and have a higher-than average salary (BlockTalk).

As shown in the table above, most people living in Kitsilano have post-secondary education (80.6%); this high percentage reflects on the average yearly income of the neighborhood ($83,581), a sum well above the 2010 national average yearly income of $32,100 for unattached individuals (Statistics Canada).

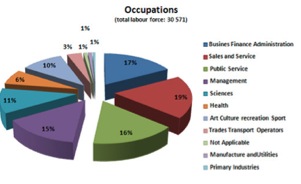

Occupations:

The middle to upper-class population dominating the Kitsilano area hold jobs in: business, management, public services, and sciences. As shown in the table above, the majority of Kitsilano residents have post-secondary education, which enables them to have careers in these higher-paying job sectors. These career paths allow individuals to afford living in this area (BlockTalk).

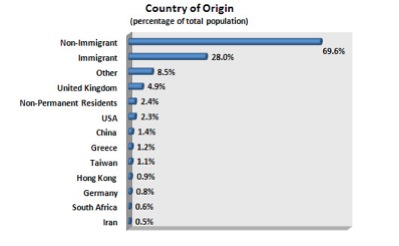

Country of Origin and Ethnic Diversity:

The vast majority of Kitsilano residents are non-immigrant Caucasians. This results in a neighborhood that is not very racially diverse; this can be attributed to the high cost of living, which is not appealing to many immigrant families (BlockTalk).

Characteristics of the Built Form

Residential:

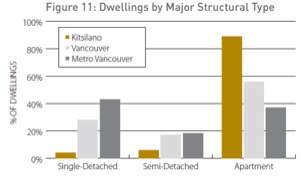

Given Kitsilano’s high density, the majority of its neighbourhoods consist of apartments at a rate of 89% out of its total dwelling units. Kitsilano has 33% more apartments than the Vancouver average and 52% more than the entire region. The rest of Kitsilano’s dwelling units are comprised of 6% semi-attached homes and 4% are single family homes (BIA).

Less than 4% of Kitsilano’s dwelling units consist of Craftsman style residential architecture of which twentieth century homes located on Macdonald Street are exemplars. Craftsman homes, also called heritage homes, have a distinct traditional design as revealed in their triangular roofs, detached garages, and front porches facing tree-lined streets. The design of these neighbourhoods creates a friendly neighbourhood vibe for its residents and enhances Kitsilano’s heritage and historic value.

Kitsilano’s heritage is also reflected in historic buildings such as the St. Augustine’s Church on 7th Avenue built in 1911 and the former Canadian Bank of Commerce on West 4th Avenue built in 1909. Heritage homes and historic buildings are seen as valuable representations of Kitsilano’s history and unique character.

The City’s Heritage Bylaw protects designated heritage buildings from “unsympathetic” construction or excavation (Metro Vancouver). Moreover, zoning laws applied to heritage residential neighbourhoods require that any new built homes must conform to the style of Craftsman homes in order to preserve the character of these communities. The city’s protection of these buildings prevents any development that would alter the character of the buildings and neighbourhoods.

The Heritage Bylaw also poses a barrier to the city’s plans to increase density in accommodating population growth. The City of Vancouver has thought of more creative ways to increase density without altering the character of the heritage neighbourhoods such as the construction of laneway homes (Kalman 93).

Commercial:

Kitsilano’s major commercial district is 4th Avenue, an 8-block strip which is mostly C-2B zoning which permits a wide array of goods and services such as retail goods and beauty services (BIA). The maximum height of these buildings is 12.2 metres. Part of the development on 4th Avenue also permits C-3A zoned buildings for light manufacturing and residential buildings with a maximum height of 9.2 metres and must be in accordance to preserving the character of the area (City of Vancouver).

Parks:

Kitsilano’s geographical location exposes it to the best of British Columbia's beauty with a vast array of waterfront development including parks. Vanier Park is the largest park in Kitsilano and is situated along English Bay under the Burrard Bridge accessible at Chestnut Street and Whyte Avenue. Sited at Vanier Park are the Vancouver Museum, Maritime Museum and H.R. MacMillan Space Centre adding to Kitsilano’s historical culture. Walking along the east side of Vanier Park will connect to Kitsilano Beach Park which is rated as one of the “Top 10 Sexiest Beaches in North America” by Forbes Traveler magazine (Dyck). In addition to Kitsilano Beach Park’s outdoor pool, tennis court and basketball court, in 2010 Vancouver’s largest and most accessible playground was built at the park as a legacy of the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games.

Transportation Infrastructure

Roads:

The city of Vancouver has its own unique grid system of street names and numbered avenues. Avenues run east-west with 1st avenue starting in Kitsilano (south of York Avenue) and increasing southbound. Kitsilano’s arterial roads are Cornwall Avenue, West 4th Avenue, and West Broadway running east-west while Arbutus Street, Macdonald Street and Burrard Street run north-south. Cornwall Avenue and Burrard Street link to the Burrard Bridge connecting to downtown Vancouver. West 4th Avenue connects to the Granville Bridge which also links to downtown Vancouver.

Pedestrian, Cycling, & Public Transit Infrastructure:

Kitsilano is a walkable and bicycle friendly neighbourhood offering ample pathways, sidewalks, crosswalks and bike racks for pedestrians and cyclists. One of the most popular trails used by walking and cycling commuters is the seawall connecting Kits to English Bay and other neighbourhoods in Vancouver. Most errands and shopping can be done by walking since residential areas are in close proximity to the commercial area. Moreover, Kitsilano generally offers limited parking space, therefore walking, cycling and transit are ideal modes of transport when exploring or residing in the Kitsilano region; however, many people still opt to use their vehicles. In addition to arterial roads and trails available to cyclists, a number of side streets such as 10th Avenue and Balaclava Street have been designated as bike routes to accommodate the increase of cyclists in recent years.

The main bus routes in Kitsilano are buses #4, #84 and #99 B-Line operating along West 4th Avenue and West Broadway to UBC. The highest level of transit ridership takes place along the Broadway corridor. TranLink has revealed that over 100,000 trips are made per day by mostly students. Due to increasing ridership, plans have been proposed for a rapid transit system connecting Broadway Station to UBC. Currently, Translink and the Provincial government are conducting a study that will evaluate the UBC-line Rapid Transit plan (“UBC Line Rapid”). The implementation of a rapid transit line running through Kitsilano could potentially help decrease traffic congestion and parking problems.

Residential Densification in Kitsilano

Densification

The issue of residential densification is complex and is not unique to Kitsilano, but affects many established neighbourhoods in Vancouver. There are multiple dimensions that contribute to the densification debate, including environmental sustainability, neighbourhood “livability”, economic pressures, population growth, and, as is especially relevant in the Lower Mainland, physical constraints on the spatial extent of urban development.

Residential densification is largely inevitable in much of Vancouver, including Kitsilano; a rising population and bounded space ensure it (Metro Vancouver 2009). There is considerable civic debate regarding the right way to address and build for a denser city. The downtown model of high-rise podium towers is favoured by many influential actors in the debate, including policy makers and property developers, for its’ high ratio of dwellings to ground space. As noted by William Rees, high density, or compactness of the urban form has numerous sustainability benefits: "the associated density and consequent energy and material savings associated with condos and high-rise apartments, compared to singly-family houses, can reduce that part of the per capita urban ecological footprint associated with housing type and related transportation needs by about 40 percent" (Rees 81). However, this style of development has been criticized for inaffordability, and insensitivity to the character of the surrounding neighbourhood; additionally, high-rise towers may not be the most ecologically sustainable method of densification, due to heat energy losses and carbon-intensive building materials (cement, etc.). Less intrusive densification solutions that have been implemented in Vancouver include laneway homes and basement suites, which alleviate financial stress on homeowners and address the regional rental housing shortage, while maintaining the single-family dwelling character of the neighbourhood. Densification by low to mid-rise mixed-use buildings on arterial streets has been suggested by UBC Architecture professor Patrick Condon as the most environmentally friendly form of dense residential development, "because it has the most number of shared walls possible, can be shaded by trees and other buildings from both sun and wind, and requires less elaborate and less expensive to run elevators and heating and cooling systems than do point towers" (Condon 99). Beyond its' environmental benefits, this style of residential development allows for considerable densification without dramatically altering a neighbourhood’s character.

Kitsilano: Densification in Context

The process of residential densification in a neighbourhood such as Kitsilano is worthy of analysis due to its implications upon the neighbourhood itself, but also upon the city as a whole, since Kitsilano is a destination location for many more people than just those who live there. Indeed, a certain level of local density supports commercial activity on Broadway and West Fourth Avenue, which is one major factor in drawing shoppers and visitors in from other areas of Vancouver and the Lower Mainland. However, as an area that has historically developed as a predominantly low-rise apartment and single-family dwelling neighbourhood, the degree and pattern of residential densification that should be allowed is a contentious issue. As mentioned above, strategic mid-rise, mixed-use densification along arterial streets is one way to significantly increase density in a way that is sensitive to a neighbourhood’s character. Pursuing this type of development along the north-south arterials in Kitsilano, such as Macdonald and Arbutus, would be one such way to meaningfully increase density in the area without significantly altering the “feel” of the neighbourhood. With regards to densification in Kitsilano and elsewhere, concerned parties include current and potential residents (owners and renters), municipal policy makers, and those involved in the real estate, development, and associated industries.

To complicate matters relative to other neighbourhoods, the Squamish First Nation, who had traditionally lived in the area prior to their removal during the establishment of Vancouver, are planning to build at least two high-density residential towers on reserve land at the south end of the Burrard Bridge, on the eastern edge of Kitsilano. (Mason 2012) This type of development is consistent with that in the downtown peninsula, just across the bridge, but would contrast starkly with the single-family homes and mid-rise walkups in Kitsilano to the west.

Preliminary Explanation and Underlying Factors

The underlying factors of the increased population density in Kitsilano are varied, but everything relates back to demand and supply. With a growing number of inhabitants mostly due to migration, Vancouver is becoming more dense. Moreover, safe neighbourhoods, quiet streets, community etc. are all very desirable features that home buyers and renters look at when choosing a neighbourhood, but they come at a high cost. Some underlying factors of the continuous densification of Kitsilano are developer profit in the current housing market - which is tied back to demand and supply, and “greenism” - the attempt to make a community sustainable and lower the carbon impact of residents.

Vision Vancouver's plan for Density

The main problem that the city is facing is its own idea of sustainable development differ from the residents idea of the community in Kitsilano. The city’s Vision Vancouver campaign, led by mayor Gregor Robertson, aims to make Vancouver the “Greenest City” in the world by 2020. (Vision, 2012) Of the four aspects of the Vision Vancouver plan, 3 of them relate to urban housing: “Affordable Housing and Homelessness,” “Safe, Liveable Communities,” and the “Greenest City” initiative. (Vision, 2012) For example, one of the affordable housing solutions that the city has come up with is the introduction of row-homes and stacked housing. (Bula, 2012) These additional housing units are complimentary to the high- and mid-rise developments which are also looked at favourably by the city. The benefit of row-homes and stacked housing are that they offer ground-level entrances, often small yards for children to play in or families to enjoy, and still have a neighbourhood feel. At the same time, they also increase density of the neighbourhood by fitting more people and families per lot. This leaves the pre-existing residents fighting for green space and as few vehicles as possible, which is part of their own idea of sustainability. There is in fact a discord between the desires of the residents and the plans of the city.

Research on this topic must be extended beyond academic to include local documents such as letters written to politicians or newspapers, newspaper articles, and local political campaigns. These are the sources that really expose the discourse: residents are not opposed to sustainability or even density, but they are wary of their neighbourhood becoming overcrowded or even worse, unsafe or unclean. The letters point out the underlying factors that have been identified by residents through perception and experience of the neighbourhood itself.

Overpopulation and Immigration

One of the revealing documents was published in the February 25th, 2012 issue of The Vancouver Sun, a book review making a point against urban densification subtitled “Instead of encouraging people to flock to urban environments, what about cultivating interesting communities in so-called hinterlands?” (Douglas, 2012) This is a perfect example of a conclusion drawn from a local resident that addresses both the good intentions of eco-density, but also protecting the neighbourhood from becoming over-populated. The underlying factor identified by the author Todd Douglas is the mass rural to urban migration that has increased world-wide over the past century. To an extent, creating communities in outlying areas is being seen in areas such as Surrey, Port Moody, and Coquitlam, but that is not enough to stop the density crush in Kitsilano. In fact, 87% of immigration to the Metro Vancouver area occurred in outlying regions, but counter-intuitively that actually added pressure to the Kitsilano neighbourhood. (Douglas, 2012) This is because the 13% of immigrants who opted to settle in the heart of the city, including Kitsilano, were in the market for a quaint, urban neighbourhood - and they had the money to buy it. As the demand for housing rises, so do prices. The housing market in Vancouver is out of line with its labour market, creating a demand for lower-cost housing that is not being supplied by the market. (Douglas, 2012) Douglas’s final argument is that in order to keep neighbourhoods from becoming monotonous and over-inflated in price, developers should work towards fostering community in outlying areas, which would please the ears of many Kitsilano residents. This is a good example of a plan that had potential to benefit member of the existing community in Kitsilano, provide developers with profit potential, and absorb incoming immigrants.

Market Development in Kitsilano

Another underlying factor for the perceived overpopulation problem in Kitsilano can be teased out from former Vancouver mayor Sam Sullivan’s recently shelved, but nevertheless influential Eco-Density project. Sullivan explained the state of the issue to journalist Daniel Wood of The Georgia Straight as they fittingly took a walk through Kits Point and discusses the history of the plan, inspired by Jane Jacobs’ “Vancouverism.” (Wood, 2012) The development of a variety of mid-rise apartments was meant to foster livability and community. Ideally, by providing a mix of residential, commercial, and institutional services within a compact, walkable distance, people would not need their cars, thus opening space up in the streets for public transit use, conversion to green space, etc.

Sullivan lays out the issues the Eco-Density project that the residents have been arguing. New condo buildings (mid-rise or not) do not actually solve the issue of providing more affordable housing opportunities. Owning a home, even a condo, will remain expensive because there is no incentive for developers to invest in social housing or any type of low-end market housing, there is no profit. The space left to develop in Vancouver is so incredibly limited, and the population is estimated to double in the next 50 years, so anything but market housing is a bad investment. (Wood, 2012)

The protection of the neighbourhood and structures themselves is something that residents are careful to conserve. Many heritage structures in the neighbourhood are being renovated and restored. Owners and landlords are taking a Do-It-Yourself approach to governing density and providing rental units in their neighbourhood. The rise in laneway houses and split housing (basement suites, duplexes) is a result of this, but it is a painstaking job, costly, and it will only absorb a portion of the demand for rental units in the neighbourhood. (Wood, 2012)Even so, this is a popular response from within the Kitsilano neighbourhood because it gives residents ownership over the issue of governing density. If they provide a rental suite, they can choose who lives there, thus retaining some of the control over the safety and community on their block. Rent collected also acts as a subsidy for the owners of the home, addressing the affordable housing issue from two perspectives: renters and owners. These are all compelling reasons to protect the existing neighbourhood, if not for its antique charm, then for the social and economic benefits.

The city has responded by introducing re-zoning by laws that make these types of renovations more easily attainable. At the same time, the city introduced a program to invite developers to compete for the limited land in Kitsilano that is due for redevelopment. A variety of row homes and stacked housing up to 3.5 stories tall is set to appear. 20 developers have applied to receive special permits for newly re-zoned lots, which all appear within one block of arterial ways through Kitsilano and Dunbar. (Bula, 2012) The project so far has been far more successful in Kitsilano than Dunbar, which is more well-known for its single standing homes. (Bula, 2012)

The idea of developers getting a hold of the land still sits uneasily with many of the local residents. Downtown has been called "monochromatic" before. The exact same process is slated to happen just across the Burrard Street Bridge if this land goes to developers in Kitsilano. On the other hand, Frances Bula of the Globe and Mail compares this project to a similar one in Portland, where historic single-family houses are intertwined with modern stacked housing to create a pleasant, diverse neighbourhood. (Bula, 2012) Perhaps a compromise can be reached and even is in the process of being reached, but factors such as affordability and rental units complicate the matter in Kitsilano.

Sustainability can also be attested as a factor in the densification of Kitsilano. Urban residents produce one tenth the amount of greenhouse gasses as their suburban foes, but how many people can the urban community sustain? (Wood, 2012) The Eco-Density project was entirely designed around density as a way to lower carbon footprint of residents. However, residents may not measure the sustainability of the community entirely in terms of carbon emission per capita.Wood points out that urban natural “green” space, peace, low noise and light pollution, air and water quality, and other community values are actually being threatened by developer proposals claiming eco-friendliness through density. This is just another case where the vision of sustainability of the residents differs from that of the city.

Policy Recommendations

Informed by our above discussion, it can be acknowledged that, given the pressing requirement for more residential capacity in Vancouver, densification in Kitsilano and elsewhere in the region is all but inevitable. There are numerous potential policy approaches to densification, from small scale solutions such as legalizing basement suites or laneway homes, to large scale high-rise condominium development. These solutions vary in their efficacy and suitability for unique neighbourhood contexts. In the case of Kitsilano, we advocate further mid-rise, mixed use development along arterial streets such as Arbutus and MacDonald, similar to existing developments seen on stretches of Broadway and West Fourth Avenue; in more residential, quieter areas of the neighbourhood, basement suites and laneway homes are acceptable densification measures that also practically serve to improve housing affordability. High-rise residential towers, as seen on Vancouver's downtown peninsula, are not a recommended solution, as they would not fit in well with Kitsilano's established character and would be politically unpalatable. Additionally, policy makers should take steps to ensure access to affordable / social housing in an increasingly densified Kitsilano, and there are tools available for leveraging developers to achieve this goal. The three pillars of sustainability (ecological, social, economic) should all be considered and appropriately balanced in the regulation of residential densification developments (or redevelopments/renovations) in Kitsilano.

Sources

Bain, Alison. "Re-Imagining, Re-Elevating, and Re-Placing the Urban: The Cultural Transformation of the Inner City in the Twenty-First Century." Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century. 4th Ed. Bunting et al. [eds]. Don Mills, ON, CAN: Oxford. Print.

BIA West 4th Avenue. "Kitsilano 4th Avenue Neighbourhood Profile". Shop West 4th.2006. Web. 14 Oct. 2012. <http://www.vancouvereconomic.com/userfiles/kitsilano-neighbourhood.pdf>.

Bourne, Larry S. and David Ley, eds. The Changing Social Geography of Canadian Cities. Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993. Google Books. Web. 26 November 2012.

Bula, Frances. "Affordable-housing plan would allow row houses, town homes." The Globe and Mail 27 Sept. 2012. Web. <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/affordable-housing-plan-would-allow-row-houses-town-homes/article4573701/>

Chandler, Maggie. "The History of Kitsilano, Vancouver." Vancouver Real Estate. 5 Feb. 2010. Web. 19 Oct. 2012. <http://www.vancouverreflections.com/the-history-of-kitsilano-vancouver/>

Christopher T. Boyko, Rachel Cooper, Clarifying and re-conceptualising density, Progress in Planning, Volume 76, Issue 1, July 2011, Pages 1-61, ISSN 0305-9006, 10.1016/j.progress.2011.07.001. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305900611000274)

City of Vancouver. Zoning & Development Bylaw 3575. Home. 31 Dec. 2011. Web. 19 Oct. 2012. <http://vancouver.ca/your-government/zoning-development-bylaw.aspx>.

Condon, Patrick. 2010. Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post-Carbon World. Print. Washington: Island Press.

Condon, Patrick M. "Vancouver in 2050: The Transit City." 22 Feb. 2012. www.TheTyee.ca.

Douglas, Todd. "City-Boosting Book Lauds Our Spaces." The Vancouver Sun Feb. 2012: C.4. Print.

Dyck, Darryl . "10 sexiest beaches now include Vancouver's Kitsilano - British Columbia - CBC News." CBC.ca - Canadian News Sports Entertainment Kids Docs Radio TV. Canadian Press, 7 July 2009. Web. 1 Nov. 2012. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/story/2009/07/07/bc-vancouver-sexy-kits-beach-forbes.html>.

"Greer’s Beach Part of Vancouver’s 125 Year Anniversary." Kits' Neighbourhood Blog. 6 Apr. 2011. Web. 19 Oct. 2012. <http://www.kitsilano.ca/>.

"History of Kitsilano." Nick Sushi. <http://nickssushi.wordpress.com/history-of-kitsilano/>

Kalman, Harold, and Robin Ward. Exploring Vancouver: The Architectural Guide. Vancouver, BC, CAN: Douglas & McIntyre, 2012. Web.

"Kitsilano." City of Vancouver. www.vancouver.ca.

"Kitsilano History & Heritage." www.KitsCondos.ca.

"Kitsilano Lifestyle and Demographics." Greater Vancouver Neighbourhood & Community Information. Web. 19 Oct. 2012. <http://www.blocktalk.ca/>.

Lee, M., Villagomez, E., Gurstein, P., Eby, D., Wyly, E. 2008. Affordable EcoDensity: Making Affordable Housing a Core Principle of Vancouver’s EcoDensity Charter. Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives.

Ley, David and Cody Dobson. Are There Limits to Gentrification? The Contexts of Impeded Gentrification in Vancouver. "Urban Studies Journal Foundation." Volume 45, Issue 2741, October 13, 2008, Pages 1-29, DOI: 10.1177/0042098008097103. http://usj.sagepub.com/content/45/12/2471

Mason, Garry. How the Squamish First Nation is Reshaping Vancouver. Vancouver Magazine. http://www.vanmag.com/News_and_Features/How_the_Squamish_First_Nation_is_Reshaping_Vancouver.

Metro Vancouver. 2009. Metro 2040 Residential Growth Predictions. http://www.metrovancouver.org/planning/development/strategy/RGSBackgroundersNew/RGSMetro2040ResidentialGrowth.pdf.

Rees, W., 2010. Getting Serious about Urban Sustainability: Eco-Footprints and the Vulnerability of Twenty-First Century Cities. Canadian Cities in Transition. 4th Ed. Bunting et al. [eds]. Don Mills, ON, CAN: Oxford. Print.

Statistics Canada. 2010. Average Income After Tax by Economic Family Types. Statistics Canada Catalogue. Ottawa. Version updated June 2012. Accessed 26 November 2012.

"UBC Line Rapid Transit Study: About the Study." TransLink. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.translink.ca/en/Plans-and-Projects/Rapid-Transit-Projects/UBC-Line-Rapid-Transit-Study/About-the-Study.aspx>.

Vision Vancouver. Last updated 17 Oct 2012. Web. <http://www.votevision.ca>.

Wood, Daniel. "Vancouver's density debate pits Sullivanism versus the ideas of Jane Jacobs." The Georgia Straight 7 June 2012. Web. <http://www.straight.com/article-702636/vancouver/sullivanism-vs-jane-jacobs>.