Course:FRST370/Projects/Community forestry in the reconstruction of Sendai after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake

How community forestry is engaged in the reconstruction of Sendai after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

This case study will discuss how local community and individuals together with local government reconstruct Sendai after the Great Earthquake in 2011. It uses different resources including governmental survey, news, and journals to explore the topic. This case study talks about the components of community forestry in Sendai, Japan. It examines the tenure arrangements and what actions are taken to rebuild the forestry system. It also explains the importance of forestry in the reconstruction process, and how community benefits from it. Community acts as an important part in recovering and actions are made to help reconstruction. This case study talks about the actions of government, community, and individual taken through reconstruction. Though it has been 7 years after the earthquake happened, this area is still under construction. So this case study states some advice for further efforts.

Description

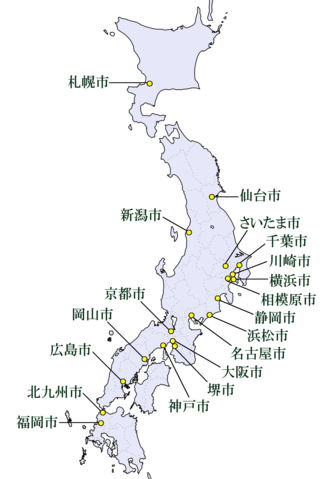

Sendai is the capital city of Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, the largest city in the Tōhoku region, and the second largest city north of Tokyo. The Great East Japan earthquake occurred at March 11th, 2011. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan, and the fourth most powerful earthquake in the world since 1900. The earthquake triggered tsunami and caused enormous damage including the nuclear accidents.

Over the centuries, communities have planted coastal forests as barriers against the sea. Of the 230 kilometers of protective coastal forests, two-thirds were heavily damaged by the tsunami (Cyranoski, 2012). There is only one single pine tree left after the catastrophic damage, and it has become a symbol of the local society's reconstruction (Edahiro, 2011).

According to the assessment done by the Ecological Science Working Group, Integrative Biology Committee of the Science Council of Japan, Tōhoku area must overcome the extensive salt damage challenges if communities want to support agriculture and rice cultivation again (Edahiro, 2011).

The land cover and land use (LULC) changes a lot after the earthquake. Abandoned farmlands and wildlife numbers have increased in the evacuation zone and surrounding area. The crop species are changed, some plants can no longer be cultivated due to the effects of tsunami. There is a high possibility that LULC will change in the future. Abandoned farmlands have become grasslands and are anticipated to ultimately change into forest (Ishihara & Tadono, 2017)

30% of the total area changed to barn land, 10% of the overall area changed for artificial use. Sand dune vegetation and coastal forest were vastly reduced in all surrey regions, and most were transformed through man-made developments or changed into barren lands. The seaweed beds, Zostera beds seabird breeding sites and benthos living landscape, were damaged at different degrees (Ichihashi, Horii, Tsukamoto, Someya, Terasawa, Iki & Abe, 2016).

Trees play an important role in coastal area. The coastal forests providing a wind break that stops san form blowing inland, and there is evidence that the forests have slowed tsunami waves resulting from some smaller quakes. The trees that stood saved lives in other ways. Some people who missed the call to evacuate were able to climb to safety and wait for rescue (Cyranoski, 2012).

Tenure arrangements

The forest covers 67% of land in Japan, which is the second highest rate in the world (Tajima, 2010).

| Land use and forest use (total 37 million ha) | |

|---|---|

| Forest | 67% |

| Farm | 13% |

| Others | 8% |

| Residential | 5% |

| River | 3% |

| Road | 3% |

| Plain | 1% |

More than half of the forestland is owned by individuals. The National Forest is 31% (7.8 million ha), Public Forest is 11% (2.7 minion ha), Private Forest is 58% (14.6 million ha).

| Forest Ownership (total 25 billon ha) | |

|---|---|

| Private | 58% |

| National | 31% |

| State, city, Village (public) | 11% |

From the 2008 report of Ministry of Forestry, Japan. The forest land divided into 3 parts: planation, natural and unstacked land.

| Planation | Natural | Unstocked land | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private Forest | 45% | 50% | 5% |

| National Forest | 30% | 65% | 5% |

| Public Forest | 45% | 50% | 5% |

The land tenure has changed in the history of Japan, and the recent four categories are: owner-farmer, part-owner, part-tenant, and tenant (Hewes, 1949).

- Agriculture land is divided into "owner-farmer" land, which is land cultivated by an owner, and "tenant-farmer" land, which is land cultivated by a tenant.

- The Owner-Farmer Establishment and Special Measures Law provides for transfer of agricultural land form owners to tenants. Its stated purpose is to establish ownership widely in order to stabilize the status of cultivators, increase production and promote democratic tendencies.

- Land is selected for purchase by the land commission of the city, town or village in which the land is situated. The plan is passed to the prefectural governor who consummates the purchase on behalf of the government. Which means government have the authority to buy the land from its owner and sell land to eligible persons.

- The lease of land must be in writing.

- All farm households can participate in the election of commissioners of the agricultural land commissions.

Administrative arrangements

The government of Japan is a constitutional monarchy in which the power of the Emperor is limited and is relegated primarily to ceremonial duties. Government is divided into three branches; the Legislative branch, the Executive branch and the Judicial branch.

| Emperor of Japan | (the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people) | |

|---|---|---|

| Executive branch | Prime minister | the head of the Cabinet, the government and commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (Article 72, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan, 1947). |

| Cabinet of Japan | Administer the law faithfully; conduct affairs of state. (Article 73 of the Constitution of Japan, 1947) | |

| Ministries of Japan | The Ministries of Japan consist of eleven ministries and the Cabinet Office. Each ministry is headed by a minister of State, which are mainly senior legislators, and are appointed from among the members of the Cabinet by the Prime Minister.

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries are one of the ministries. It has Fisheries Agency and Forestry Agency. ("Ministries and Agencies". Government of Japan Website) | |

| Legislative branch | National Diet | It is a bicameral legislature, composing of a lower house, the House of Representatives, and an upper house, the House of Councillors.

The Diet responsibilities include the making of laws, the approval of the annual national budget, the approval of the conclusion of treaties and the election of the Prime Minister. (Article 1, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan, 1947) |

| House of Representatives | The legislative power of the House of Representatives is considered to be more powerful than that of the House of Councillors. It is able to override vetos on bills imposed by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority, however, be dissolved by the Prime Minister at will.

(Article 7, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan, 1947) | |

| House of Councillors | The House of Councillors can cause the House of Representatives to reconsider its decision. The House of Councillors cannot be dissolved by the Prime Minister.

(Article 54(2), Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan, 1947) | |

| Judicial branch | Supreme Court | It is the court of last resort and has the power of Judicial review.

4 lower courts: the High Courts, District Courts, Family Courts, and Summary Courts. ("overview of the Judicial System in Japan". Supreme Court of Japan) |

| Local government | The local governments of Japan are unitary, in which local jurisdictions largely depend on the national government both administratively and financially (Local government, n.d.). |

Affected Stakeholders

The farmers, individual and collectives, are being affected the most. Agriculture and rice cultivation have been one of the most important industries of Japan for a very long time. After the catastrophe, the area have to overcome the extensive salt damage and the radioactive challenges if communities want to support agriculture and rice cultivation again (Edahiro, 2011).

The local government, Sendai government illustrated some relative policies for the reconstruction after the Great East Japan Earthquake (Sendai, n.d.). These policies encourage individuals, communities and government to work together to reconstruct the city and natural system:

1. Sendai’s efforts: disaster prevention and disaster risk reduction measurement. These projects include restoration of the waste water treatment facilities and providing support for improving the earthquake resistance of detached houses and condominiums. The city of Sendai offers support for recovery and reconstruction of disaster areas by dispatching their staff members and providing relief supplies.

2. 3-dimention: Self-help: individual residents will take action to secure safety for themselves and their families during a disaster. Mutual aid: local community organizations such as neighborhood associations will take action to secure the safety of their local communities during a disaster. Public assistance: the government will work to improve tangible aspects of disaster prevention such as infrastructure and facilities as well as intangible aspects such as ‘self-help’, ‘mutual aid’.

3. Resident’s efforts: education for residents and children-How to make a community “disaster-resilient”. disaster risk reduction brochure for non-Japanese residents prepare for disasters together. Sharing experiences and lessons learned form the tsunami and our Disaster Risk Reduction(DRR) efforts with future generations.

Sendai city also a specific plan for reconstruction after the Earthquake (2018), which community forestry engaged in:

1. Agricultural and food frontier zone:

- Building an agricultural and food frontier.

- Restoring and recovering farmland.

- Supporting farmers in enhancing their management base.

- Launching suburban agriculture.

- Promoting the sixth industry.

2. Exchange promotion project to “promote the features of the city and its reconstruction efforts”:

- Attracting international conferences and conventions, such as the United Nations World Conference on Disaster Reduction.

- Conducing a large-scale tourism campaign, etc.

- Inviting facilities to make Sendai more attractive and vital.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

Japanese society attached highly importance to the reconstruction after the disaster, and many outside organizations and groups contribute to the restoration process.

Tokyo University of Agriculture started a project called East Japan Assistance Project, which aimed to help check the facilities and students whose family had been affected by the earthquake. It also provided financial aid to these students. This project would be act to resolve issues in response to requests for help from the disaster zones, rather than acting according their own interests (Monma, Gotō, Hayashi, Tachiya & Ohsawa, 2015).

1. Student volunteers: the farmers asked the project to send student volunteers to help them with some tasks like recovering the strawberry greenhouses and helping to grow strawberries. International students have also taken part in these voluntary activities.

2. Farming team: check for radionuclides, obtaining an assurance form the national government or Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO)that they would compensate farmers by buying agricultural produce if radionuclides were detected and produce could not be sold.

3. Soil fertilization team: remove salt in farmland. They test the soil in farmland and provide information about this process to the farmers affected by the disasters. Their works include recovering the strawberry greenhouse, recover Tsunami-damaged paddy fields, and recover farmland contaminated by radioactivity.

4. Forest recovery team: collect data and analyze the accumulation of radionuclide in forests and the penetration of cesium into trees.

There are many workshops that the Great East Japan Earthquake Recovery Assistance Project held with farmers aiming to proceed the revival of agriculture in Tōhoku Area. They use a three-dimensional laser measurement system with MMS(mobile mapping system) to reveal the changes in the topography. This system can be applied several fields related to community development, such as improving road infrastructure, or forecasting agricultural production (Monma, Gotō, Hayashi, Tachiya & Ohsawa, 2015).

1. The Faculty of Regional Environment Science and its 3 departments -- the Department of Forest Science, the Department of Bioproduction and Environment Engineering, and the Department of Landscape Architecture Science: they use multiple theories, such as education theory, planning and technology theory, policies and economic theory, to help revive rural communities.

2. Agricultural revival workshops: The workshops is a means to discuss how to work toward resuming commercial agriculture in line with the community’s visions for its future.

Discussion

The recovery works in the damaged coastal disaster-prevention forests are underway, to be completed within ten years (Forest Agency, 2015).

Coastal forests helped to reduce the power of tsunami, slow the speed of tsunami to arrive on land, capture driftage and contributed to weakening the disaster. They are effective to certain extent against waves less than 6 meters and significantly effective for those waves which are 3 meters and below (Takehiko, 2012).

Recovery and strengthening of the coastal forests should be done cooperatively by the people and the governments of that region, volunteer groups and everyone in Japan and around the world.

Timber is suitable for architectural material and engineering material. It should be stored in future so that it may be used as emergency material.

The Great Forest Wall Project (JFS, 2013) aims to build a green seawall that will reduce the force of tsunamis and prevent people and personal possessions from drifting out into the ocean in an ebb tide.

There are alternative plans for the construction while facing the conflicts with nature (2017):

1. Coastal defenses:

One of the alternative initiatives is the Millennium Hope Hills project, which is a park system that will provide an evacuation area and buffer against tsunami impacts through a system of engineered tree-covered mounds and elevated pathways.

Another alternative example is the restoration of the coastal forest belt designed to buffer tsunami impacts. Replanted trees will be on elevated mounds to create additional room for the roots to take hold as well as provide an additional buffer against tsunamis and debris.

2. Coastal livelihoods:

WWF-Japan works to improve coastal livelihood an fisheries. The Nature and Livelihood Recovery Project, included natural environment, marine pollution, and fishery economics surveys.

Assessment

The speed of reconstruction after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake is relatively slow. According to Reconstruction Agency figures, over the last two years more than 100,000 people displaced by the Great East Japan Earthquake have moved from provisional lodging to permanent accommodations. As of January 2018, though, approximately 75,000 evacuees remain in temporary housing, including around 20,000 who reside with relatives and another 20,000 in temporary prefabricated structures (2018).

Japanese government funds budgeted for reconstruction and transferred to local governments are stuck in banks across the tsunami-ravaged northeast, a Reuters review of budget and bank deposit data and interviews with bank officials reveals. The central government has paid out more than $50 billion directly to local governments in Miyagi, Iwate and Fukushima prefectures, the areas hardest hit by the disaster. But about 60 percent of that money remains on deposit in the region's banks (Uranaka & Slodkowski, 2014).

Apparently, the power of the government is the strongest. Government has experts to make the reconstruction plan and policy and staffs to implement them. It also has the greatest influence and can call on the masses and companies to participate in the event. All departments of the government have their own special work and accusations. The cooperation between the departments can make the country operate. But sometimes, the structure of the government has its drawbacks, for example, the promotion and implementation of policies cannot be timely conveyed. Also the national government does not know the local situation in a timely and accurate manner, so that it might be hard to provide right directions. This situation often causes some conflicts and delays.

Local communities also have strong power, they are affected stakeholders who value their lands and property. They live in that area and care about the environments. They know the nature condition better than outsiders and often willing to protect them. Personal strength is not enough to change the overall environment, but individuals who unite to form groups have more ability to accomplish what they want to accomplish. Their voice is more easily heard and responded to by the society. Communities can also receive funding and help from more sources., which help them recover faster.

Interested outside stakeholders, like the student volunteers and NGOs, have different level of powers, they can provide financial or physical assistance. They might not have the power of making policy, but they can be the implementer. They play a similar role with social media, attracting more resources for local help.

Recommendations

I have different recommendations for the governments, local communities, and the interested outside stakeholders. These suggestions might not be sufficient, but they can help more or less for their current situation.

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| Government | There are several recommendations for the central government:

For the local government:

|

| Local communities | Local communities should plant and protect their vegetation and forests together. People can organize meetings regularly to discuss the current level of progress and future plans. Coastal forests need to be managed and maintained, and local people are undoubtedly the most suitable people to do this work. Some influential people in the local area, such as actors, athletes, and politicians, can promote their hometowns on suitable occasions, attract more people to travel to this place, and drive economic development. Local communities can create some local specialties that can be used as representative or label of this area. It also benefits the exportation, which can be a financial support for construction. |

| Interested outside stakeholders (e.g. NGOs, volunteers) | Universities, regional or international, can provide more activities, like student volunteers and researches. These activities can both help the local communities and improve the abilities of students as well as the reputation of schools.

NGOs can set up a special project or foundation to provide technical and financial assistance to local people. Some organizations can also take the opportunity to train technicians with relevant qualities, like forests maintainanceor forest science, to prepare for future challenges. |

References

Annual Report on Forest and Forestry in Japan(summary). (2015). Forestry Agency. Ministry of agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan. Retrieved November 14, 2018 from http://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/hakusyo/27hakusyo/attach/pdf/index-1.pdf

Cyranoski, D. (2012). Rebuilding Japan: After the deluge. Nature,483(7388), 141-143. doi:10.1038/483141a

Edahiro, J. (2011). How Did the Great East Japan Earthquake Affect Ecosystems and Biodiversity?|JFS Japan for Sustainability. Retrieved October 08, 2018, from https://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id031172.html

"Government Directory." JapanGov. Accessed November 14, 2018. https://www.japan.go.jp/directory/.

Hewes, L. I. (1949). On the Current Readjustment of Land Tenure in Japan. Land Economics,25(3), 246-259. doi:10.2307/3144795

Ishihara, M., & Tadono, T. (2017). Land cover changes induced by the great east Japan earthquake in 2011. Scientific Reports,7(1). doi:10.1038/srep45769

MIC. (2009). Local autonomy in Japan: current situation 7 future shape. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, Japan. Retrieved November 14, 2018 from http://www.clair.or.jp/j/forum/other_data/pdf/20100216_soumu_e.pdf

Monma, T., Gotō, I., Hayashi, T., Tachiya, H., & Ohsawa, K. (2015). Agricultural and forestry reconstruction after the great East Japan earthquake: Tsunami, radioactive, and reputational damages. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55558-2

Ichihashi, O., Horii, D., Tsukamoto, Y., Someya, T., Terasawa, H., Iki, S., Abe, S. (2016). Survey of Impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the Natural Environment in Tohoku Coastal Regions. Ecological Impacts of Tsunamis on Coastal Ecosystems Ecological Research Monographs,395-410. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-56448-5_23

Sendai -Towards a Disaster-Resilient and Environmentally-Friendly City. (n.d.). Retrieved October 09, 2018, from http://sendai-resilience.jp/en/efforts/government/development/

Sendai City Earthquake Disaster Reconstruction Plan, Digest Version(2011, December) Retrieved October 09, 2018, from https://www.preventionweb.net/applications/hfa/lgsat/en/image/href/824

Six Years After Tsunami Japan is Finding Ways to Work with Nature. (2017). Environment & Disaster Management. Retrieved October 09, 2018, from http://envirodm.org/post/six-years-after-tsunami-japan-is-finding-ways-to-work-with-nature

Takehiko, O. (2012) The Role of Forests in the Great East Japan Earthquake and Sustainable Forest Management and its Usage. Retrieved October 10, 2018, from http://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/kaigai/pdf/keynote_final_english.pdf

Tajima, D. (2010). Forestry in Japan: Solutions for the Future. World Forestry Center. Retrieved November 14, 2018 from

https://www.worldforestry.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Dtajima_2010.pdf

The State of Recovery in Tōhoku Seven Years After 3/11. (2018). Retrieved November 14, 2018, from https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00169/

Uranaka, T., & Slodkowski, A. (2014). $30 Billion Meant To Rebuild After The Japan Tsunami Is Still Sitting In Banks. Retrieved November 14, 2018, from https://www.businessinsider.com/r-special-report-tsunami-evacuees-caught-in-30-billion-money-trap-2014-10

Volunteers Building 'Great Forest Wall' Tsunami Barrier from Earthquake Debris|JFS Japan for Sustainability. (2013). Retrieved October 10, 2018, from https://www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id032922.html

三割自治 "Local Government". (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2018, from http://countrystudies.us/japan/116.htm "裁判所 Courts in Japan." 裁判所|Justices of the Supreme Court. Accessed November 14, 2018. http://www.courts.go.jp/about/sosiki/gaiyo/index.html.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST370. |