Course:FRST370/Projects/Analysing Vancouverism: The Role of Community in Vancouver's Olympic Village, British Columbia, Canada

In 2010, Vancouver hosted the Olympic Winter Games, with an Olympic Village that became a ground-breaking model for urban ecodesign known as ‘Vancouverism’. The Olympic Village is located on traditional, unceded, ancestral territory, shared and overlapping between the First Nations of Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh [1].

Historically, the land was used by the Squamish First Nation as a winter residence. In 1959, the first European explorers arrived (Richardson, an English sea captain, renamed the area "False Creek"). Following the industrial boom of the 1950s-60s, the land was repurposed for housing in the 1970s [2].

During the controversial bid to host the 2010 Olympic Games, the community of Vancouver accepted the proposal, stipulating a condition to include affordable housing. Unfortunately, the Olympic Village failed to deliver an inclusive housing plan. Today it is recognised as a pioneering ecodesigned neighbourhood and green community, despite persistent challenges to community management ([3] p.7).

Description

Vancouverism

Vancouverism is the popular name for a style of urban planning, pioneered in Vancouver, a coastal city in western Canada.

The founding idea of Vancouverism is "to bring homes and workplaces closer together [… with] progressive notions about livability, environmental compatibility, fiscal management, entrepreneurial governance, and inclusive public engagement as well as an emphasis on elegant urban design.” ([3] p.3)

With the creation of dense neighbourhoods filled with amenities, the vision of Vancouverism is to foster a diverse community spirit ([3] p.4). The ideas of Vancouverism are present in numerous cities (Toronto, Portland, San Francisco, Helsinki, Madrid, Seoul) by transforming of old industrial districts, creating urban landscapes, encouraging walking and cycling, and fostering “compact but comfortable residential areas” ([3] p.6) as an environmentally-conscious solution to urban pressures.

Community

Vancouver’s Olympic Village hosts a diverse community, including:

- First Nations: Squamish and Urban Aboriginal

- City of Vancouver elected officers

- Residents

- Real estate developers

- Green technology developers

- Urban commerce

- Minority groups

These stakeholders have shared or overlapping rights, however they are brought together as one community under the concept of Vancouverism.

Historical context

Heritage and Democracy

The City of Vancouver acknowledges that the Olympic Village is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. These overlapping territories were characterised by tidal flats with bountiful seafood [4][5].

Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal peoples have built a home on an integrated territory, which, since 1886, recognises both the Salish territory and the City of Vancouver as owners of the land ([6] p.5).

→ The duality of tenure in Canada is similar to Senegal [7] in that there are two recognised systems of power: First Nations’ (or indigenous) hereditary power as well as democratic power of elected rulers.

Colonial and post-colonial history

The history of South False Creek, the site of the current Olympic Village, is a complex succession of tenure agreements [2].

| Decade | Event |

|---|---|

| 1860s | Early Industrialisation by European settlers (start of Industrial Boom). |

| 1950s | Industrial disinvestment (start of Industrial Bust). |

| 1970s | Remediation of disused industrial land and rezoning for housing. |

| 1990s | the City of Vancouver presents a report, aiming to:

(a) remedy the poor air quality by creating communities in which commuting would be unnecessary, thereby decreasing traffic pollution; (b) build an inclusive community, with mixed-used amenities and mixed-income housing. The City of Vancouver experiments with new technologies through “green community” investments. |

| 2000s | The City of Vancouver bids to host the 2010 Winter Olympic Games. In response to local controversy, the City presents:

(a) recommendations to prevent urban displacement, especially of the poor and marginalised communities; (b) the promise to build 4000+ affordable housing units. |

Hosting the 2010 Olympic Winter Games

The community of Vancouver accepts to host the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, conditional to the creation of affordable housing as a by-product [2]. The South East shore of False Creek is leased for Olympic development. Urban designer planned the development of Olympic infrastructure based on 3 pillars of sustainability: economic, social and environmental benefits [3].

As an Olympic host city, Vancouver has repurposed a signification portion of the $6 billion Olympic investments, and benefited in land economy, tourism and amenities [8].

“At the macro level, the 2010 Winter Olympics have helped in the realization of Metro Vancouver’s longstanding ambition to fashion the region into a network of transit-oriented, walkable, neighbourhoods with a world-renowned quality of life.” [8]

Tenure arrangements

Today, the Olympic Village of Vancouver contains various types of tenure (land agreements):

- Areas of undeveloped and undefined land are publicly owned by the City of Vancouver

- The public realm (ie: streetscape) is publicly owned and maintained by City of Vancouver ([9] p.15)

- Airspace parcels (the air above a surface) are privately owned [10]

Real estate:

- Condominium strata and apartments may be privately owned, or collectively owned by private property owners in their representative Strata Councils [11]

- Real estate is privately owned and managed by real estate enterprises (eg: Concert Development, Bental Kennedy) and private property owners [12]

- Affordable housing is publicly owned by the City of Vancouver [13].

Administrative arrangements

The City of Vancouver summarises the chronology of land agreements and administrative arrangements at the Olympic Village from 2002-2012 [14].

| Month | Year | Action |

|---|---|---|

| November | 2002 | Multi-party agreement of financial contributions, legal responsibilities and sporting legacy of 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. |

| June | 2003 | Vancouver is officially declared the host city of the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. |

| July | 2005 | The Official Development Plan for the Olympic Village incorporates mixed-use urban planning, with focus on affordable residential areas, community services and environmental protection. |

| January | 2006 | Amendment of the Official Development Plan to reduce affordable housing requirements by 80%. |

| April | 2006 | Millennium Properties Ltd. becomes the designated Village developer. The purchased land remains the property of the City until the end of the Games. |

| October | 2006 | Public Hearings are opened to review and discuss rezoning with the local community. (Approximately 400 attendees, 60 comment forms submitted). |

| June | 2007 | The City of Vancouver (“the City”) covers all financial risk for Games (estimated $750 million CAD). |

| January | 2009 | Vancouver Charter is amended by the Province of British Columbia to allow the City to borrow and lend money in order to meet commitments for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. |

| February | 2009 | The City takes a loan on behalf on Millennium Properties Ltd. Millennium is anticipated to repay the loan through the sale of market residential units, market rental buildings, commercial spaces or through inventory financing, after the end of the Games. |

| February | 2010 | Olympic Winter Games occur. The Olympic and Paralympic Village receives LEED Platinum designation. |

| August | 2010 | Default and settlement of Millennium loan debt. |

| February | 2011 | Re-branding of the Olympic Village as The Village for commercial and private market sales. |

| May | 2012 | Creekside Community Centre opens. |

Affected Stakeholders

The affected stakeholders are those members of the Olympic Village who are dependents or hereditary stewards of the land. They not named nor explicitly acknowledged in the City of Vancouver’s communications in terms other than “the community” [14]. However, the City of Vancouver Dialogues Project ([6] p.7) acknowledge the following affected stakeholders:

- Youth

- Elders

- Immigrants

- First Nations

- Urban Aboriginals

These affected stakeholders receive a voice through the Dialogues Project, a slow process of mutual understanding and respect of the three communities who interweave Canada’ cultural fabric:

- the original inhabitants, the First Nations;

- the urban Aboriginal peoples who have come to Vancouver from other territories;

- immigrants, those who are newcomers to Vancouver ([6] p.5).

Marginalised and racialised communities or individuals [15] have no voice; their interests are pursued by public pressure (such as protests for affordable housing [16]).

→ The colonial history of land claims in Vancouver bares similarities to Apaa, Uganda, where the State government sold communal land without consent from the local community.

‘Vancouverism’ has blurred boundaries between the constituent communities within a large interwoven urban community, due to their shared experiences and history ([6] p.10). Even so, self-definition is sought by community members to navigate the complexities of race, oppression, and identity ([6] p.25).

Interested Stakeholders

The interested stakeholders have interests or power in the Olympic Village, however they are arguably not culturally tied or dependent upon that land. They include:

- The City of Vancouver (owner of Public Realm: streets, affordable housing, etc.)

- The Village developers (eg: Millennium Properties Ltd.)

- Financial institutions (eg: Fortress Credit Corp.)

- Urban commercial properties (eg: London Drugs, Terra Breads), who typically have time-limited tenure with a rapid turnover

- Private property owners*

- Ecosystem-based services (eg: water management, recreation, tourism and maritime trade [17]

- Urban agriculture: Community gardens, green roofs, rain gardens, street trees ([18] p.101-102).

Stakeholders 1, 2, 3 occupied dominant positions of power during the development and re-development of the Olympic Village from 2002-2012 [14]. Additional interested stakeholders (4-7) were non participant in the legal arrangements for the Olympic Village.

*Higher valued properties have de facto stronger claims to their property rights [19].

Discussion

Goals of Vancouverism

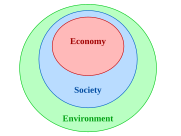

The goals of Vancouverism are built around the Millennium Developmental Goals, with three pillars of sustainability: economy, society, and environment, see as integrated issues. These goals translated as [5]:

- Canada's first net zero multi-unit residential building;

- Affordable housing;

- Natural ecological habitat;

- Building the island (neighbourhood with a community spirit).

The urban design of Vancouver’s Olympic was a feat in sustainability [3]. However, the affected stakeholders – the local community – felt the major weakness in the rising inequality and housing crisis [19]. De facto, the development of the Olympic Village became a battle between businesses and residents [2].

→ The slippage between de jure and de facto rights is similar to the case of Senegal [7]. In both cases, the amended tenure agreements represent a withdrawal of previous legal rights; as a result, the more marginalised residents became incapable of exercising their property rights.

Community Dialogues

The voice of capital economists is recognised with authority; hence, the City of Vancouver sought “Development sector experts” to provide advice on the development of the Olympic Village [14]. The dialogue between city planners and local residents was a commendable effort in participatory decision-making. Nonetheless, the Dialogues Project [6] explored the struggles of meaningful community dialogue within Vancouverism. Indeed, the Public Hearings of 2006 [14] were similar to the Forest Protection Committee meetings in West Bengal, India (under Joint Forest Management) in facing the challenge of engaging with an community representation [20]. The Dialogues Project (a multi-stakeholder initiative) operates on slow time-scales, too slow for meaningful impact in the land planning decisions of the time-pressured Olympic Village. (The 2010 Olympic Winter Games was required to followed the International Olympic Committee’s tight timeline, enforced with high international pressure). The difference in time-scales leads to “slow violence” [21] wherein the vulnerable and marginalised communities bear a disproportionately large burden of social and economic problems.

Finances

The construction of the Olympic Village exceeded its budget by 2006. As a result, the Official Development Plan was amended such that 600+ social housing units were cut and funds redirected to support green technology infrastructure. The promise of inclusivity was neglected; unaffordable housing was further exacerbated by Olympic speculation on real estate. The economic burden placed upon resident taxes to alleviate business taxes, in an arguable patronage of businesses by the City [2].

→ The influence large businesses (interested stakeholders) is similar to the “distance decay” felt in Zanzibar, Tanzania, where the interest of the majority ethnic group have greater influence in governance and government [22]. This issue is also noticeable in Creston, British Columbia, with the practice of “regulatory capture” [23].

Recommendations

Upon consideration of the balance of power in the Olympic Village, and despite the efforts of Vancouverism, the marginalised community have been negatively impacted (by amendments to the mixed income residence plan) whereas the wealthy community of interested stakeholders has benefited in the negotiation stages, city planning amendments and Olympic Village legacy [8][14][19][24].

The promise of mixed income housing in the Olympic Village was lelt unfulfilled after the 2006 amendment of the Official Development Plan [14]. Since housing affordability remains a significant challenge for sustainability [3], a new amendment can be envisioned to reinstall the initial promise of affordable housing units. Speaking in the legal language of Official Development Plans, perhaps with lawsuits, may rectify the shortfall of affordable housing in Vancouver.

The City of Vancouver and the interested stakeholders of Vancouverism have benefited most from Olympic discussions, amendments and legacy [8][14]. In light of Calgary’s interest in hosting the 2026 Olympic Winter Games [25], the importance of dialogue with affected stakeholders is highlighted (particularly with marginalised stakeholders)[6][15]. Canadian Olympic events have learnt from their mistakes in cultural exploitation of First Nations [26], however, First Nations remain an example of marginalised communities in Vancouver[27]. Their grief is deeply-rooted in land rights; a solution may be found in unraveling the conflicting land claims [28] and elevating the voice to the level of a political institution in Canada.

References

- ↑ City of Vancouver. (2018a). False Creek Olympic Village destination walk. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/false-creek-olympic-village.aspx

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Antrim, S. (2011). Whose Village?: A Brief History of the Olympic Village Development. Retrieved from http://themainlander.com/2011/06/01/whos-village-a-brief-history-of-the-olympic-village-development/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Barnett, J., & Beasley, L. (2015). Ecodesign for cities and suburbs. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. (2018a). False Creek Olympic Village destination walk. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/false-creek-olympic-village.aspx

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 City of Vancouver. (2018b). Olympic Village. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/olympic-village.aspx

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Suleman, Z. (2011). Vancouver Dialogues: First Nations, Urban Aboriginal and Immigrant Communities. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/dialogues-project-book.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ribot, J. (2009). Authority over Forests: Empowerment and Subordination in Senegal's Democratic Decentralization. Development And Change, 40(1), 105-129. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01507.x

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Tomalty, R. (2016). The Legacy of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Retrieved from https://islandpress.org/blog/legacy-2010-winter-olympics-vancouver

- ↑ PWL Partnership Landscape Architects Inc. (2009). Southeast False Creek Private Lands: Public Realm Enrichment guide. Vancouver, BC: City of Vancouver. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/public-realm-guide.pdf

- ↑ Romero, A. (2013). The Property Rights of Airspace. Retrieved from https://www.dummies.com/education/law/the-property-rights-of-airspace/

- ↑ Province of British Columbia. (2017). Strata Councils. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/housing-tenancy/strata-housing/operating-a-strata/roles-and-responsibilities/strata-councils

- ↑ Concert Realty Services Ltd. (2018). The Concert Story. Retrieved from http://www.concertproperties.com/about

- ↑ Howell, M. (2014). So who actually owns all that land at the Olympic Village? Retrieved from https://www.vancourier.com/opinion/so-who-actually-owns-all-that-land-at-the-olympic-village-1.2180327

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 City of Vancouver. (2014). Olympic Village Chronology of Events and Community Benefits. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/olympic-village-fact-sheet.pdf

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Menzies, N. K. (2007a). Chapter 1: Introduction. In Our forest, your ecosystem, their timber: communities, conservation, and the State in community-based forest management. New York: Columbia University

- ↑ Jessa, A. R. (2009). Place image in Vancouver : vancouverism, ecodensity & the resort city. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0132827

- ↑ Wilson, S. (2010). Natural Capital in BC’s Lower Mainland: Valuing The Benefits From Nature. Burnaby, BC: David Suzuki Foundation. Retrieved from https://davidsuzuki.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/natural-capital-bc-lower-mainland-valuing-benefits-nature.pdf

- ↑ Brown, G. and Mooney, P. (2013). Ecosystem services, natural capital and nature’s benefits in the urban region: Information for professionals and citizens. Vancouver, BC: School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, University of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://www.bcsla.org/sites/default/files/documents/Sent%20Final%20Ecosystem%20Services%20Natural%20Capital%20%20Natures%20Benefits%20%20In%20the%20Urban%20Region%20Information%20for%20Professionals%20%20Citizens.pdf

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Fong, F. (2017). Income Inequality in Canada: The Urban Gap. Toronto, ON: Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=2ahUKEwi6pJm38vDeAhWOJjQIHfm7C74QFjADegQICBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cpacanada.ca%2F-%2Fmedia%2Fsite%2Foperational%2Fsc-strategic-communications%2Fdocs%2Fg10363-sc_income-inequality-in-canada---the-urban-gap_final_eng.pdf%3Fla%3Den%26hash%3DFBDD71D48EBAA8B9ECAAB49461C3043BF5E4BFD6&usg=AOvVaw2lJejGNmvWmK7V_fwvPZjF

- ↑ Banerjee, A. (2007). Joint Forest Management in West Bengal. In: Springate-Baginski O. and Blaikie, P. Forests, people and power: the political ecology of reform in South Asia. London, UK: Earthscan Publications Ltd. pp. 221-239; 245-250.

- ↑ Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Menzies, N. K. (2007b). Chapter 3: Jozani Forest, Ngezi Forest, and Misali Island, Zanzibar. In Our forest, your ecosystem, their timber: communities, conservation, and the State in community-based forest management. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Bullock, R.C.L. and K.S. Hanna (2012). A “watershed” case for community forestry in British Columbia’s interior: the Creston Valley Forest Corporation. In Community forestry: local values, conflict and forest governance, pp. 82-99. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Gold, K. (2018). In Vancouver’s Olympic Village, good things come to those who wait. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/real-estate/in-vancouvers-olympic-village-good-things-come-to-those-who-wait/article23231401/

- ↑ City of Calgary. (2018). Olympic Bid Public Engagement. Retrieved from http://www.calgary.ca/CSPS/Recreation/Pages/Calgary-2026-Olympic-bid/Olympic-Bid-Public-Engagement.aspx

- ↑ Adese, J. (2012). Colluding with the Enemy?: Nationalism and Depictions of “Aboriginality” in Canadian Olympic Moments. The American Indian Quarterly, 36(4), pp. 479-502.

- ↑ O'Bonsawin, C. (2010). ‘No Olympics on stolen native land’: contesting Olympic narratives and asserting indigenous rights within the discourse of the 2010 Vancouver Games. Sport in Society, 13(1), pp., 143-156.

- ↑ Sellars, B., & Wilson, B. (2016). Price Paid: The Fight for First Nations Survival. Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks.

| This conservation resource was created by Caroline Pilat. |