Course:FRST370/2021/ Mi'kmaq Moderate Livelihood Fishery

This study will delve into the history of the Mi'kmaq First Nations, specifically regarding colonial power over their traditional harvesting and hunting rights. The main focus is Lobster and Eel fishing: done by commercial fisheries in Nova Scotia and the Sipekne'katik First Nations Moderate Livelihood Fishery operated out of Saulnierville Wharf. Eels are a mysterious creature and a large connector of Indigenous groups around the world[2]. It will recount historic court cases and events leading up to the present day. This study features an interview with someone who married into the Mi'kmaq First Nations. Information gathered from her interview will be implemented throughout the piece. This study will detail the case in terms of who are the stakeholders and rights holders, the tenure arrangements, and the political complications.

This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST370. | |

Description

Location

This Case Study takes place in the maritime Province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaki and Wabanaki First Nations. This case study dives specifically into the Mi'kmaq First Nation, which is a smaller nation part of the wider Mi’kmaki Nation, and the Sipekne'katik community fishery run out of Saulnierville Wharf, opened in 2020.

History of the Mi'kmaq First Nation

The Mi'kmaq First Nation has lived on what settlers claimed as "Nova Scotia" since time immemorial, living in harmony with themselves, the land, and the sea. There are seven historical districts of the Mi'kmaq First Nation spanning all of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and expanding into New Brunswick as well [4]. These districts originate from their creation story, which speaks of the creator: Kisúlk, whose lessons guide the Mi'kmaq people in day-to-day actions[5]. The Nation has a strong understanding of their connection to ancestry and descent from a place that guides their beliefs and actions. Everything they do coincides with their traditional principle of Netukulimk, it is shown through traditional customs and laws, as well as everyday actions based on sustainability. Netukulimk is a governing principle that centres around the sacred responsibility to the future seven generations (McMillan, 2021). This term dictates their way of life and, important to note in this study: their guidelines for fishing.

When colonizers arrived on Mi'kmaq traditional lands, they viewed the Mi'kmaq peoples as lesser, criminalizing their traditions and way of life [6]. In order to maintain their lands and way of life, the nation signed treaties with the colonial government which promised their hunting, fishing and ways of life could continue as long as their allegiance was pledged to the British Crown [6].

Moderate Livelihood

Entwined in the traditional principle of Netukulimk, is the term ‘Moderate Livelihood’. This is a term revolving around the idea of taking what you need to live, and nothing more. To the Mi'kmaq First Nation this term means self sufficiency [2]. The ability to supply for themselves, their family, and their nation without help from the colonial government.

Colonially, this term has become controversial and politically entangled in many ways. From our intervieewee's point of view, settlers have this misunderstanding that First Nations take too much from the land due to greed, causing controversy. In reality if every Mi'kmaq person went fishing, they would still be completely outnumbered by non-Indigenous fishers[2].

Under the Peace and Friendship Treaty between the Mi'kmaq Nation and the government signed in the 1700s, the Mi'kmaq Nation has the right to hunt and fish for a Moderate Livelihood. The controversy then becomes the definition of Moderate Livelihood from a colonial standpoint versus a Mi’kmaq standpoint. This term was never explicitly defined in law leaving room for debate and leading to unjustified charges. There are times and cases where this right is upheld in court (The Marshall Case of 1999), yet there is also a backlash and sense of loss from the settler community when this happens. An example is the riots and protests from commercial fisheries in 2020 when the Sipekne’katik First Nation (Part of the Mi'kmaq Nation) opened their Moderate Livelihood Fishery [7].

Supreme Court Cases

Simon Case (1985)

The Simon Case involved James Matthew Simon who was a hunter from the Mi’kmaq community. Simon was charged with the possession of a shotgun and shell during the closed hunting season. This led to a violation of the Provincial Lands and Forest Act. After this violation it was assumed that the Mi’kmaq community were not capable of making treaties and were represented as “savages roaming around unorganized and did not have capacity to enter into an international treaty.”[8] However, Simon was arguing the rights he had from the 1752 treaty to hunt and fish. Which later followed with the Supreme Court deciding that he was protected under the Mi’kmaq treaty for hunting rights on reserve land. This was an important stepping stone from the Canadian government to recognize Mi’kmaq rights in Canada, and treaty rights for all First Nations in Canada. Although this decision had a small impact on protecting and acknowledging Mi’kmaq rights to hunt and fish, it led to the future decisions for the Mi’kmaq community to be able to hunt and fish outside of reserve lands.

Sparrow Decision (1990)

The Sparrow decision involved Ronald Sparrow of the Musqueam band, who was charged with fishing with a net longer than allowed in 1984. Sparrow argued that his right to fish was protected under Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act and did not align with the license granted to his Band. Soon after the Supreme court decision in 1990 recognized his right to participate in food fishery, but declined Aboriginal rights to commercial fish. [9] The decision undermines aboriginal sovereignty and self-government, creating little leverage for aboriginal communities to build a sustainable livelihood from the fishery. After these negative implications, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans implemented the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) in response to the Sparrow decision. This meant that indigenous individuals without a license that are part of their community Band could eat and preserve fish they catch, share this fish through traditional celebrations and share with elders and family members. However, the Mi’kmaq First Nation Peoples at this time were allowed to fish on a small scale but could not sell their catch which has been an increasing problem for their livelihoods. Although the government's approach to conservation is fish management, the Mi’kmaq approach to conservation is connected by the wellbeing of fish stocks, economic, political, and spiritual wellbeing of the community.

Marshall Case (1999)

The Marshall case involved Donald Marshall who was a part of the Mi’kmaq First Nation Band and The Supreme Court of Canada. Donald was arrested for fishing and selling eels without a license. Although Donald and many other individuals were trying to survive on the harvesting and selling of eels to make enough money for the off season he was faced with a huge court case that got a large amount of media coverage. After long periods of court cases, and jail time, The Marshall decision gave Mi’kmaq communities the right to hunt and fish in order to maintain moderate livelihood. As the DFO’s seasonal licenses infringed on the treaty rights of the Mi’kmaq.[9] This also created conflict between First Nation fishers and Settler fishers, as violence between the two emerged as more Mi’kmaq commercial fisheries were introduced. Resulting in a protest that broke out where non-native fishers destroyed native fishing gear. This was one of the many damaging effects from the court cases and media coverage towards Donald. He was also suffering from underlying health conditions.

Tenure Arrangements

Fishing Agreements used by the Mi’kmaq communities:

Food, Social and Ceremonial licenses under the DFO

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) grants Food, Social, and Ceremonial (FSC) licenses to Indigenous communities such as the Mi’kmaq across Canada for a wide range of species. Typically, FSC licenses are developed after consultations with the community, and the terms and conditions of the licenses are based on specific considerations present within each community, such as species, amount to be fished, area, gear, and times.[10]

FSC license conditions reflect regulations, as well as management measures and catch monitoring and reporting requirements, all of which promote safe, orderly, and sustainable fishing. The catch is allowed to be eaten ceremonially and culturally but not sold. It is not known how many FSC licenses there are actively in Mi’kmaq communities.

Communal commercial license under the DFO

Community commercial licenses are allocated to First Nations communities by the Allocation Transfer Program (ATP) or the Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative (PICFI) through a mutual agreement. The PICFI program was designed to support communities to build economically and environmentally sustainable fisheries. The ATP program is meant to provide communities with access to commercial fishery enterprises. Communal commercial licenses are party based with the First Nation identified as the license eligibility holder. These licenses are issued annually. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) issues communal licenses to First Nations as a component of a capacity-building strategy aimed at developing strong fisheries entities. This encourages First Nations participation in fisheries resource management while also improving catch monitoring and reporting across fleets. For Indigenous communities, this allows access to grants and funding for investments in vessels and fishing gear as part of a business plan, training and mentoring, and commercial fisheries enterprise management skills. [11] For the lobster fishery, Marshall communities possessed 347 communal commercial licenses in 2020 with a total value of close to $58 million in 2018.[12]

Proposed Moderate Livelihood licenses under the DFO

DFO proposed a moderate livelihood license would have been issued under the Aboriginal communal licensing regulations of the Fisheries Act. This license would have authorized the community to fish 500 traps using tags “validated by DFO.” The catch could then be sold “for the purposes of earning a moderate livelihood." [13]

Moderate livelihood

The treaty right to fish for a moderate livelihood, recognized by both Indigenous communities and the Constitution of Canada. This right only pertains to thirty-four First Nations within the Atlantic Canada region. This right enables the communities to provide for their own sustenance. The right to moderate livelihood is found to lack clarity and is in turn open to interpretation for self-governance of the right. Under that pretext, the applicable First Nation communities are defining their own parameters of moderate livelihood fishing within their own fisheries. This allows for community-based decision-making in all areas within the moderate livelihood fishery such as monitoring, licensing, and what they deem important.

Legal Tenure Arrangements

Legal tenure arrangements of fishing in Canada are legally created by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans under the Canadian Government. The DFO is responsible for setting the rights of use, control, restraints and management of fishing in Canada. The relationship the DFO has with the land, water, and resources is not deeply rooted in culture or spirituality like the Mi’kmaq nation. Examples of legal tenure arrangements include the Food, Social, and Ceremonial licenses and Communal Commercial licenses under the DFO.

Fisheries Act

Under the Fisheries Act, the DFO regulates the aquaculture industry focusing on the protection of fish and fish habitat. The act regulates fishing licenses, management, protection and pollution prevention. There are many regulations under the Fisheries Act relating to aquaculture including Aquaculture Activities Regulations and Marine Mammal Regulations[14]. Compliance of the Fisheries Act is measured through ensuring environmental protection is upheld to keep aquatic environments protected and marine resources productive for future generations[14].

Customary Tenure Arrangements

Customary tenure arrangements of the Mi’kmaq follow netukulimk. Netukulimk is a cultural guidance of the Mi’kmaq sovereign law regarding the management and protection of resources for current and future generations. It can be expressed through rituals and customs, lobster fishing being an example of how the Mi’kmaq may practice netukulimk. Indigenous connections to the land formed a cyclical and systematic spiritual relationship between the people and the land, resources, and water. The Mi’kmaq view life as a continuous cycle where the death of something within this cycle brings nourishment to the living. This special guidance of netukulimk is hard for non-Indigenous people to understand as they are not deeply rooted in this culture and spirituality. This way of understanding is not written, but rather understood by the Mi’kmaq people.

Administrative arrangements

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO)

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is a department under the Government of Canada that is responsible for managing the fisheries and oceans in Canada. They create laws and regulations for fisheries and oceans in Canada, holding the most decision-making power. The DFO is responsible for managing, protecting and conserving fish and fish habitats under the Fisheries Act[15].

The DFO introduced Enterprise Allocations and Individual Transferable Quota systems. This quota system privatized the right to access a public resource and does not cater to the global market fluctuations or environmental variability.[16]

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans also created the Aboriginal Fishing Strategy (AFS) in response to the Sparrow Decision in 1992[17]. The AFS is a strategy used to align the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision on the Sparrow case with fishery management of the DFO[15]. It’s objectives include providing a framework to Aboriginal fishing management in regards to the social, ceremonial and food purposes, provide Aboriginal groups the opportunity to be involved in the management of fisheries, and contribute to the economic sustainability of Aboriginal communities[15]. The Aboriginal Fishing Strategy relevant where the DFO manages fisheries and where land claim settlements do not have a fisheries management regime.

Mi'kmaq First Nation

The Mi’kmaq First Nations do not hold much power in the colonial decision-making processes and policy making. They follow netukulimk for guidance on how to manage local resources. Netukulimk is not a written law, but a way of believing, a worldview the Mi’kmaq people follow[6]. By following netukulimk, the Mi’kmaq people have managed local resources for many generations based on the communities need for food, shelter, and trade[6]. By practicing netukulimk, they follow traditional resource management needs for the whole community rather than for individual members of the community[6].

Affected Stakeholders

Mi'kmaq First Nations and Mi'kmaq Fishers

The Mi’kmaq nation and Mi'kmaq fishers are directly affected by the actions and decisions of this case study. The Mi’kmaq nation are rightsholders of the land as they hold an ancestral linkage to the territory where this case study takes place. They heavily rely on the fisheries and fish habitats in Nova Scotia and are directly subject to the effects of fishery and ocean management of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. They have relied on fishing since time immemorial for many generations in the past, present, and future. The colonial governing laws put in place by the Canadian Government and the DFO restricts their traditional fishing practices to certain seasons in the year. Restricting fishing seasons directly impacts the food source of the Mi’kmaq people and their income, infringing on their right to ‘respect Indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices’ under UNDRIP[6]. The term ‘moderate livelihood’ has been documented and used in Supreme Court cases, but has not established a legal definition. Defining the term ‘moderate livelihood’ would create a concrete basis of what is expected when this term is used.

Interview Introduction

The person we interviewed is a professor at St. Francis Xavier University and holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of British Columbia. Being a legal anthropologist she investigates how legal systems are established and how they change, the different concepts of what is right and wrong, and dispute management techniques.

She found her life partner in Donald Marshall Junior (Junior), son of 27 year Grand Chief of the Mi’kmaq Nation: Donald Marshall Sr., while studying in Halifax.

Interview Q and A

1. Is the fear the band member mentioned in your chapter [18] regarding setting negative presidents by taking something to court that loses still widely felt throughout the nation?

Answer: Generally speaking, this notion of fear surrounding the potential of setting a negative precedent is felt throughout the Nation. The fear of the court case verdict potentially contracting their rights and interfering with treaty rights is real and justified in examples where this has happened. The Benard case in 2000 went against the Marshall case decision and contracted rights. The Mi’kmaq First Nation was found guilty for harvesting on crown land as the court found no evidence of commercial native logging historically[19] (CBC, 2000).

There is a growing question within the Nation as to whether pursuing litigation is the right way to move forward with nation building.

2. How long have you been lobster/eel fishing and what got you into it?

Answer: When she met Junior, he had been released from jail for his wrongful conviction and they moved to his house in Cape Breton. They began eel fishing in 1992 and expanded to broader territory with more equipment in 93’. The main purpose of eel fishing was to make a living, the fishing allowed them to gain stamps so they could collect Employment Insurance throughout the off season. The DFO would sometimes approach them and ask them to make sure their band name was on their trap. These officers often knew they were selling but did not mind at this point.

3. Was there any controversy over you fishing, as you are not Mi’kmaq born?

Answer: She the only woman fishing, but was accepted by the community to fish due to her status as a spouse and the trust that was built. At a broader scale, there are lots of non-Indigenous spouses married into Indigenous Nations today, and the problem only evolves when the resource is not being harvested in a responsible way. This controversy and lack of clarity at a broader scale may not be fully cleared up until the Mi’kmaq Nation regains full independence.

4. Can you explain what the term netukulimkt means? For you? For the Mi'kmaq Nation?

Answer: This term is a governing principle instilled in the Mi’kmaq culture. In 1990 there was a resurgence of this word due to the rise of responsibility for sustainable harvest. It also provides a unique identifier for the Mik’maq fishers and fisheries as it is framed in terms of conservation through not overharvesting. There is a passion linked to this word to do with the environment and resources being conserved for future generations. There are a lot of people hunting and fishing outside of this principle, meaning a call for re-education and understanding of netukulimkt is recommended.

5. How would you define Moderate Livelihood, and what does this term mean to the Mi'kmaq Nation?

Answer: Moderate Livelihood is self sufficiency. For the Mi’kmaq Nation it is about getting off social assistance and being able to support themselves, their families and their nation independently from the colonial powers. This term does not refer to luxuries, it is about the basics: having food security and shelter, being able to buy clothes, pay for transportation and most importantly getting off of social assistance. Losing dependence on the colonial government: regaining the independence they had prior to colonization. Many Mi'kmaq people have begun dropping "Moderate" and only saying "Livelihood", as the term moderate can be seen as discriminatory.

Answers: Although there are cases that have upheld the right to Moderate Livelihood there are always limits to these cases. The Simmons case has less limits than the Marshall case, yet is less populated in the Media which is a limit on its on.

7. You were with Donald Marshall eel fishing in Pomquet Harbour when he was charged with 3 counts by the DFO under the Fisheries Act. Can you walk us through this experience? (How it felt during and after etc.)

Answer: They were fishing with Junior's cousin, and were fishing in a different territory. They had a connection through Juniors cousin, had asked the Chief for permission and were granted the right to fish there. They fished for six days before the DFO showed up.

The officer asked to see names and licenses. Under colonial legalities they did not have licenses, they were exercising their right to fish for a moderate livelihood under the Peace and Friendship Treaty. Junior stated this to the DFO officer, who in reply requested a net. They gave him an empty one. As the DFO officer drove off, his boat became lodged in a sandbar, striking suspicion in all three fishers as they wondered why he was out in this Bay if he did not know the landscape and the water?

Because they had done the customary tradition of requesting permission from the Chief, they were in the right; however, they were concerned the DFO officer would not understand and respect this customary law. Shortly after payday, they went out to check their nets and found all their gear was missing. It was common to have conflict surrounding gear, leaving them uncertain about who had stolen theirs. The DFO? Commercial Fishers?

Upon discovering it was the DFO, anger instantly rose inside all of them, they began calling and demanding their nets back. With no luck, and a terrible feeling in their stomachs, they left. Out Interviewee having to go back to school, and Junior heading home. Due to this, they were not able to earn a living in the off season. Come October, they were served. Three counts under the Fisheries Act: Fishing without a license, selling without a license, and selling in the off season. It was debilitating and terrifying as they had no money for legal representation and our interviewee was not protected under the treaty right as she was only under the customary spouse law which may not be recognized in court. Fortunately, a week later, her charges were dropped.

At a meeting of Chiefs, shortly after, discussing the frustration they were feeling regarding lack of right to exercise treaty rights following the Simmons case. They needed a solid case to go to court to change this, they decided on Juniors. This became known as the Marshall case of 1999. The court had already wrongfully denied him his life, how could they do that again? This brought back memories, and traumas for Junior. He carried the weight of his Nation on his shoulders and it was a terribly hard time for him. Junior had a legal team of Mi’kmaq legal scholars, the first cohort from the Marshall inquiry.

They lost at Provincial court; however, the judge intentionally wrote the verdict in a way that it could be appealed and taken to the Supreme court. By this point, fame had put Junior in the spotlight and he was getting all sorts of attention (positive, negative, and all in between). His health was deteriorating under the stress and pressure of it all.

The appeal court was racist, claiming treaty rights were gone and they could not claim traditional rights when they were fishing in a motor boat. Complete misconception of their way of life. Hearing the denial of their rights from the crown was a sickening feeling, but when they made it to the Supreme court they gained hope. When the court sided with the Junior, it was a huge moment of unity among the Mi’kmaq Nation. The DFO took the loss badly which begs the question of why settler communities see the upholding of traditional and treaty rights as a loss? The backlash was seen through violence and threats to the Mi’kmaq nation.

Industry Fisheries

Industry Fisheries such as Scotia Harvest Inc. and Clearwater Seafood Incorporated Fish in traditional Mi’kmaq waters are also considered affected stakeholders, but they are not rights holders. These fisheries have not been fishing in these waters since time immemorial, and are generally colonial operated. When regulations are changed, their capacity to harvest is directly impacted which changes their profits. Increasing numbers of fisheries operating here impacts their catch limits. Furthermore, allowing or denying the Mi’kmaq Nation to fish in the off-season would directly impact their catch, business sales, and in their eyes, the health of the lobster.

Their main objective in this industry is money based that leads to being financially viable and gaining profits. They have power in numbers, money and in some cases biases, as well as uncertainties regarding Treaty Rights (as seen when Junior was charged by the DFO). However, the court cases siding in favor of First Nation treaty rights shows where their lack of power stands.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

DFO

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is an interested stakeholder because they govern fisheries and oceans under the colonial Canadian Government. They do not have any generational connection to the land and water they govern as they have not been operating since time immemorial. The DFO is connected to the territory as they are linked to governing the fisheries and fish habitats within Canada, but do not have a long-term dependency on the fisheries or oceans to sustain their livelihoods. They have the power and ability to enforce and interpret laws and definitions to how they seem fit. They are in charge of levying fines and sanctions when the laws they have put in place are broken[9]. The objectives of the DFO are to create, implement and enforce laws and regulations regarding Canadian fisheries and oceans[9]. The DFO works towards conservation through an economic lens. They are interested stakeholders as they are the ones creating the laws and regulations on fisheries and oceans in Canada, but the workers income or means of living are not directly affected by any changes in regulations.

Conservationists

Conservationists are interested stakeholders as they have interest in conservation and protection of the lobster and fish populations, but like the DFO, they have no long term-dependency or connection to the land and water. Conservationists' livelihoods will not be impacted with any changes to regulations or laws put in place by the DFO. They provide knowledge and expertise in regards to the conservation and biodiversity requirements and standards, which help the DFO create laws and regulations on fishing. Conservationists hold the power of public trust and support, but lack the power and ability to create laws and regulations and enforce them.

Discussion

Over time the Mi’kmaq Nation has set strong precedent cases through taking a stand for their treaty rights to be upheld. However, as we have seen in cases and heard from our interviewee, a strong precedent does not always mean the court verdict goes your way. The cases mentioned above: The Simon case of 1985, the Sparrow Decision of 1990, and The Marshall case of 1999 were all cases that had good outcomes for the Mi’kmaq Nation. There was no contraction of their rights. Solid precedents were set, and their rights to hunt and fish for a moderate livelihood were upheld. Although seen as successes, none of these cases were easy, they all came with massive hardships for the First Nations communities involved, had significant money spent, and afterwards cruel backlash from settler communities. The Sparrow Decision for example, took a total of 6 years, and also resulted in what is called the Sparrow Test. This is designed for governments to determine “whether a right is existing, and if so, how a government may be justified to infringe upon it”[20]. Prior to the Marshal case, Donald Marshall Junior was wrongfully convicted of murder at the age of 17 and placed in jail for 11 years[21]. The Marshall Inquiry returned that this decision was rooted in racism. These cases also all have limits, as our interviewee mentioned, and a key one related to the Marshall case is that “the federal government retains the authority to regulate that fishery in the public interest and for conservation” [3].

When the Sipekne'katik First Nation opened a moderate livelihood fishery on Saulnierville Wharf in 2020, there was a retaliation from commercial fisheries in the area. They set a lobster pile and a boat on fire, threw rocks at cars, vandalized buildings and committed other violent acts[7]. There was an irrational fear that the new fishery would harm the already dwindling lobster population, disproven by fisheries experts[7]. To this day, the Sipekne'katik First Nation Moderate Livelihood Fishery is still in operation outside of DFO regulated seasons[22]. Chief Mike Sack has conviction and dedication to this fishery and states he is prepared to take it to court if he needs to.

The way it is now, there are important clauses in the United Nations Declarations of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) that are not being met[6]. The right to ‘self-determination of socio-economic development’ requires Indigenous People’s have access to resources and land, many of which are under being used and owned by private citizens, public agencies and industrial corporations[6]. The lack of understanding settlers, and the fishing industry have shown and continue to show towards the Mi’kmaq relationship to the land undermines their right to ‘respect Indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices’ which is declared in UNDRIP[6].

Today, Four Mi’kmaq Bands have opened fisheries; however, there regulations are created by the DFO who state they must operate within the colonially set seasons[22].This is a success they are open and have had their rights to moderate livelihood upheld. This also showcases the lack of influence and power the Nation has, as the DFO has the rights to set their regulations regarding the season, allowable catch, and amount of traps[22].

Assessment

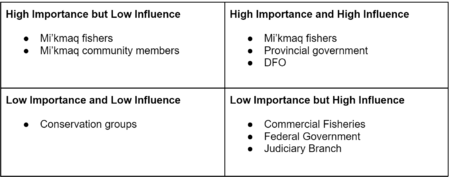

Power Assessment:

A1: Mi’kmaq fishers have high importance as they are fishing on reserve waters. Mi’kmaq fishers also have rights that allow them to harvest fish for profitable income and traditional practices. However, Mi’kmaq fishers have low influences as they are restricted to harvesting fish to financially make a living off of reserve waters. In some cases wrongful convictions and harsh fines are given to Mi'kmaq fishers that have little control and influence over DFO rules and regulations. They have low power to exert in exercising control over this, due to constraints in legal systems for their de facto rights.

A2: Mi’kmaq community members have high importance as they are representing the treaty's traditional rights that help First Nation individuals hunt and fish on reserve land and waters. However, these members do not have much influence on rules and regulations regarding harvesting and selling produce on non-reserve land and waters.

A3: The Provincial Government of Nova Scotia has high importance as they uphold treaty rights and the constitution acts that protect Mi’kmaq First Nation community. The Provincial Government also has high influences as explained in the Marshal Case, that has direct communication with the DFO that enforce rules and regulations on non-reserve land and waters.

A4: The Department of Fisheries and Oceans have high importance for which they contribute to the management of fisheries and oceans in Canada. They enforce laws and regulations for fisheries and oceans. The DFO also has high influence as they have the most decision making power that affects Mi’kmaq First Nation Fishers on and off of reserve waters.

B1: Commercial Fishers have low importance as they are not right holders but affected stakeholders. These fishers also do not have traditional or ancestral rights to the waters as they are colonial operated. They also have low influences as they are allocated licenses from the DFO and have no impact on decision making towards the Mi’kmaq community.

B2: The federal government is not directly involved in the decision-making processes in regards to the management of fisheries and oceans in Canada. Instead, the federal government has the Department of Fisheries and Oceans working under them to manage fisheries and oceans. The DFO reports to the federal government, making the federal government have high influence, but they are not directly involved in the decision-making and management of fisheries and oceans.

B3: The judiciary branch is of high influence because they make the decisions in the Supreme Court cases which then set a precedent for future cases regarding Indigenous fishing. They are not actively involved in the fisheries and ocean management in Canada so they have low importance in the power assessment.

B4: Conservation groups have low importance and are interested stakeholders. These groups have no long term dependency on waters but are interested in protection and conservation of the lobster and fish populations. Therefore, their livelihoods are not impacted by rules and regulations on the waters. They also have low influences as they are not involved with decision making regarding laws, licenses and regulations.

Recommendations

Much of the controversy found in this case surrounds the term ‘Moderate Livelihood’. This term has been documented, has been upheld in court and still does not have a concrete definition. This lack of solidarity and understanding of the meaning of this phrase is a key aspect to the struggles seen throughout this case study. If this term were to be defined legally, there would be less room for debate. However, it is important that this definition is created by the Mi’kmaq people as it is centered around their culture and belief system. For a colonial-centered committee to concisely define this term and the parameters, it may serve a disservice to the Mi’kmaq's own self-determining definition of the meaning for their communities. In order for a pathway to move forward, it will be important to listen and engage meaningfully with the Mi’kmaq Nation.

Switching from a top down management to a bottom-up management system that embeds “two-eyed seeing” would be a great step forward for the community fisheries and would improve the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. In Mi’kmaq culture, the term for "two-eyed seeing" is Etuaptmumk and is used as a guiding principle[23]. The term uses the knowledge and strengths from both a Western mindset and an Indigenous mindset. With this principle in place, there would be mutual respect, learning and understanding from both parties.

From out interviewee, re-education on the word and principles surrounding Netukulimk is important both within and outside the Nation. As well as shifting the settler mindset. Creating a positive response when treaty rights are upheld, instead of the negative connotation this situation has today.

References

- ↑ "Mi'kma'ki". Native Land. 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 J. McMillan. Personal Communication ,November 19th, 2021

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cooke, Alex (September 17th, 2020). "Mi'kmaw fishermen launch self-regulated fishery in Saulnierville". CBC News. Retrieved 11/27/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Native Land Digital (2015). "Mapbox". Native Land Digital. Retrieved 11/25/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Poliandri, Simone (2011). First Nations, Identity and Reserve Life: The Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 19–42.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Prosper, K (2011). "Returning to Netukulimk: Mi'kmaq cultural and spiritual connections with resource stewardship and self-governance". International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2: 1–14 – via Research Gate. horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 25 (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Moore, Angel (October, 20th, 2020). "Sipekne'katik chief's message to Canada is moderate livelihood fishery is here to stay". National News. Retrieved 11/25/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Pottie, Erin (2015). "Simon Case; First Nation marks victory membertou hails 1985 'turning point' for treaty rights". Chronicle - Herald – via Proquest.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 King, Sarah, J (2011). "Conservation Controversy: Sparrow, Marshall, and the Mi'kmaq of Esgenoôpetitj". The International Indigenous Policy Journal. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":5" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/aboriginal-autochtones/fsc-asr-eng.html

- ↑ https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/aboriginal_opportunities_government_resource_programs.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/432/FOPO/Reports/RP11260980/foporp04/foporp04-e.pdf

- ↑ https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fisheries-peches/aboriginal-autochtones/moderate-livelihood-subsistance-convenable/2021-approach-approche-eng.html

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Fisheries Act". Government of Canada. 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy". Government of Canada. 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ↑ Wiber, m; Milley, C (2007). "AfterMarshall: Implementation of Aboriginal Fishing Rights in Atlantic Canada". The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. 39. horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 52 (help) - ↑ King, S.J (2011). "Conservation Controversy: Sparrow, Marshall, and the Mi'kmaq of Esgenoôpetitj". The International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2.

- ↑ From Jane’s Chapter “Committing to Anthropology in the Muddy Middle Ground” she quoted a Band Member stating “The problem . . . is everybody wants to have a Marshall decision and be the guy who won, but no one wants to be the band that took on a case that may lose and set a negative precedent for treaty rights”.

- ↑ CBC News (April, 14th, 2000). [cbc.ca/news/canada/court-rules-against-native-logger-1.225318 "Court rules against native logger"] Check

|url=value (help). CBC News. Retrieved 11/26/2021. Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Salomons, Tanisha (2009). "Sparrow Case". Indigenous Foundations. Retrieved 11/24/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ McMillan, Jane (2019). Transcontinental Dialogues. Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-4343-4.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 CBC News (October 13th, 2021). "4 Mi'kmaw bands launch moderate livelihood fisheries with federal approval". CBC News. Retrieved 11/26/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Two-Eyed Seeing". Institution for Integrative Science and Health. Retrieved 11/29/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/432/FOPO/Reports/RP11260980/foporp04/foporp04-e.pdf