Course:FRST270/Wiki Projects/Socio Bosque Program Communitarian vs Individual Challenges and Benefits for Ecosystem Conservation Combined with Poverty Allleviation in Ecuador

Socio Bosque program: Challenges and benefits for ecosystem conservation combined with poverty alleviation within Indigenous territory in Ecuador

Sauca, Saywa

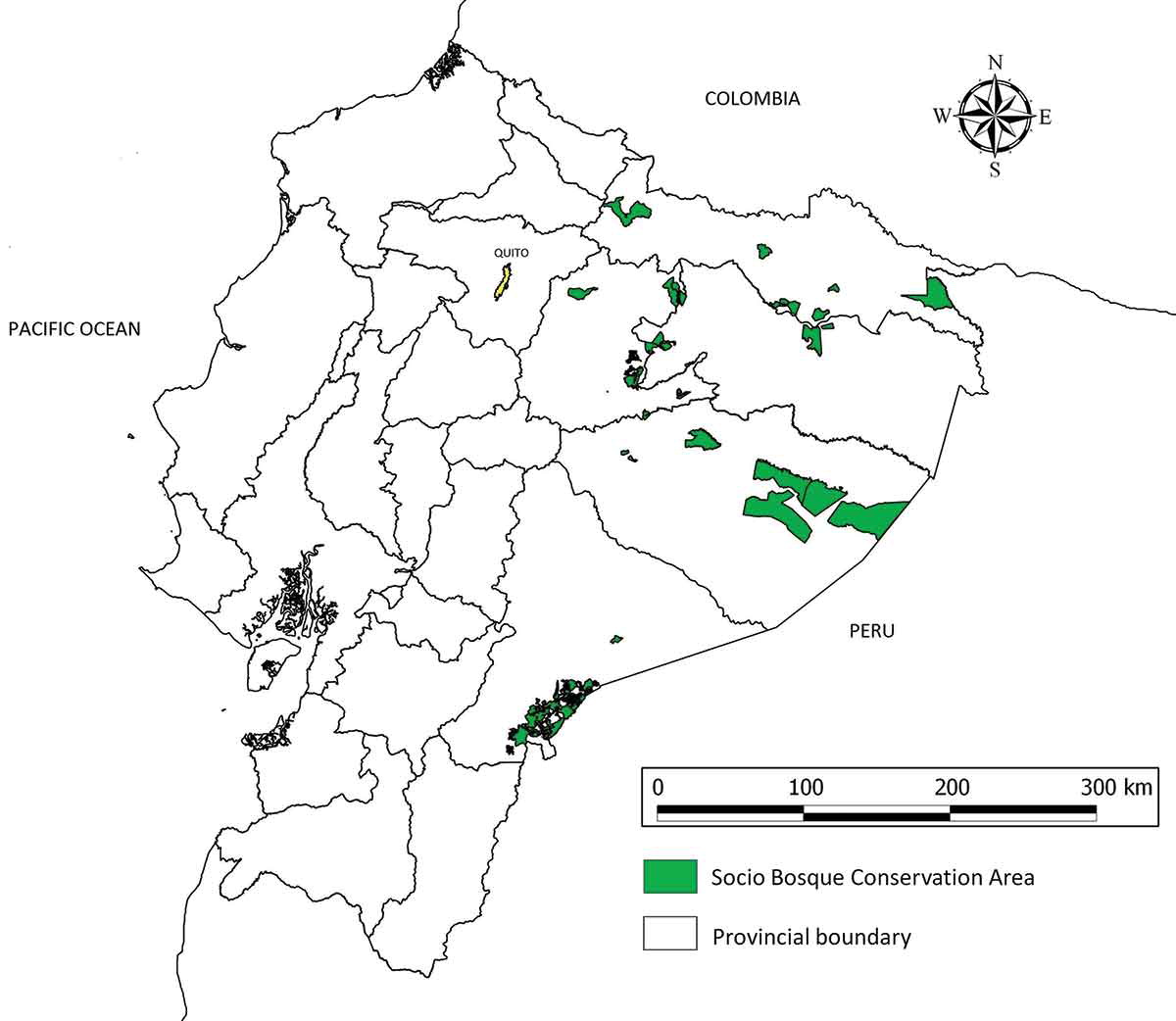

Socio Bosque Program (PSB from here onwards) is a project implemented in Ecuador since 2008 aimed to promote the conservation of forested lands and at the same to alleviate poverty rates among the forests owners—Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals and communities. This paper focuses on the Indigenous communities that incorporated their communal territory in the PSB. Forest owners receive a cash compensation for preserving the native forest from deforestation and taking care of it while complying with a set of guidelines stablished by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment (MAE). The higher the number of hectares per forest the less the compensation. Depending on the case, the owners must comply with a set of individual or community set of rules defined by themselves and other set defined by the state. Although the PSB has been a success in terms of environmental conservation, its efficacy for poverty alleviation, social justice, and respect to Indigenous rights and territory continues to be its main challenge.

Description

- Launched by the Ecuadorian government in 2008 as an effort to slow an steady loss of 200,000 hectares of native forest per year in the country’s Amazon rainforest region.

- 65% of the national forest area belongs to Inidgenous peoples, which makes them an important stakeholder group for the PSB. [1]

- The program is overseen by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment (MAE in Spanish)

- Basically, it consists in providing economic incentives for farmers and Indigenous communities who voluntarily join the program.

- People can join individually or as communities—which can be the organization of many individual freeholders or (as in the case analyzed here) Indigenous communal lands/forests.

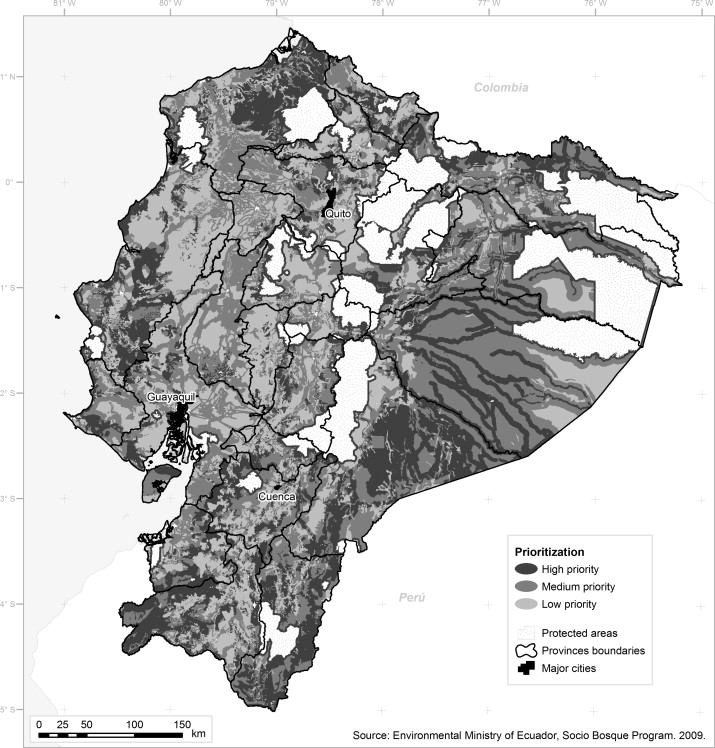

- The priority level for a property to be included in the program is determined based on the following formula: Priority level= Ecosystem service value (10 points total) + Threat level (9 points total) + poverty level (3 points total). [2]

- Incentive scale: The greater the number of hectares included in the program, the lower the price per hectare that is paid.

- Most of the Indigenous nations of the Amazon rain forest region have signed the program. [1]

| Incentive Scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Contract | Collective Contract | ||

| Hectares range | US$/ha | Hectares range | US$/ha |

|

|

|

|

This table was adapted from Krause & Loft (2013) and is the revised incentive scale introduced in 2011 by the MAE. Thus, these are the current ammounts of incentive being paid to the Indigenous communties partenered with the PSB. For a comparison and revision of the original incentive scale used since 2008 until 2011 you can visit Krause and Loft (2013) [4]p. 1174

Tenure arrangements

- The individual or community owner of the property must have legal land title inscribed in the Government Property Registry

- To include a property as Indigenous communal land, the Indigenous communities need to have legal status as such, accredited by the corresponding authority.

- The tenure arrangement of the territory included into the PSB is that of a forest management agreement.

- The community decides how mush territory they want to put under conservation, but they all are subject to restrictions and obligations stablished by the MAE. [5]

- After signing the agreement, it extends for a minimum of 20 years and renews automatically for another 20 years if notice to cancel is not given in the final year of the first contract period.

- In this time the SBP members cannot do:

- Logging, controlled burning, change in soil use, commercial hunting, affect the natural performance of the land or reduce carbon storage

- They can:

- Transfer ownership of the land (in the case of non-communal land) previously informing the MAE. But the area continues under conservation, otherwise it is considered early termination and the original executor is subject to penalties.

- They must:

- The MAE can carry out projects follow up and enter the conservation areas for monitoring at any time without the need of permission by the owners.

- The MAE, apart from the transfer of funds to the SPB members, also have to provide assistance on any related issues.

- The MAE can terminate the contract unilaterally under a certain number of violations by the executor; or early termination by the executor can happen with previous authorization by the MAE.

- Although land title and tenure are secure and protected by the local Constitution, this legality does not stop the state from developing extractive industries even within the conservation areas involved in the SBP.

- The Constitution guarantees freehold ownership of the indivisible, inalienable nature, and exclusive usufruct rights of communtarian Indigenous land. However, the state holds the power to override those rights if it declares those lands of public interest. [6]

Administrative arrangements

- The representative of the community is chosen from and by all the members. For signing the contract, he/she has to present a legal proof of representation.

- The partners (forest owners/communities) must submit an investment plan, which format is specified by the MAE, to be approved and monitored by the same Ministry.

- The MAE stablishes all the legal restrictions and obligations of the program’s partners.

- The MAE also monitors the area under conservation, but it is the partners’ obligation to protect and report any natural or human-provoked changes that take place within that area. [7]

- Notice in the image below that "participatory forest monitoring is not part of PSB's regulation." [3] However, According to Krause and Zambonino[3] "if its is included and developed in conjuction with the communities, it can strengthen the regulatory demands that prohibit logging and commercial hunting. " p. 235

Affected Stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Main relevant objectives | Relative power |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous peoples | Low (especially, once they enter the contract) |

Interested Outside Stakeholders

| Stakeholders | Main relevant obectivest | Relative power |

|---|---|---|

| MAE |

|

High |

| NGO Acción Ecológica (Ecologic Action) |

|

High-medium |

| REDD+ |

|

High (in the sense of its attractiveness to the Ecuadorian government) |

| German bank KWF and other private sectors |

|

Medium-high (its funding compromises the Ecuadorian government to align with the REDD+ goals) |

| CONFENAIE (Confederation of Amazonian Indigenous Nationalities from Ecuador) | Medium-high | |

| Ecuadorian government | High |

Discussion

The main objectives of the SBP are forest conservation and poverty alleviation. However, the policies designed to guide the program overlooked, and continue to do so, the social aspect giving greater importance to the environmental aspect. While the conservation rates make of the program a success, the polemics about violation and undermining of Indigenous rights and ongoing poverty make of the program a relative threat. Some local and international critiques assert that lower economic incentives per higher amount of territory under conservation stimulates individual land property. In the future, that will facilitate intromission by the state into Indigenous territory, especially for resources extraction or control of ecosystem services. The higher incentives per smaller hectares estimulates the fragmentation of territory and is already generating some internal conficts. [7]

Moreover, because PSB is planned to be integrated in the REDD+ startegies, some Indigenous leaders and environmental activists opose and criticize the current format of the program. They see REDD+ as the new "CO2lonialism of the forests" p. 102. [7]

There is also the issue of unfair distribution of money among the community members, which partly contributed to the failure of the social aspect of the program. The great majority of the members in some of those communities partnering with SBP do not know the contract guidelines or how much money the community receives per territory under conservation or how much is their fair share.[1]

Assessment

The high power-concentration in the MAE overwhelmingly favors the Ecuadorian government. [7][6]This issue raises concerns regarding Free, Prior, Informed Consultation (not consent) that must be done with the PSB partners to incorporate the program into any the REDD mechanism or carbon market. [6] On the other hand, the lack of community participation in stablishing regulations and forest monitoring renders just Indigenous peoples as guards against their own traditional livelihood. Because of the exclusion of monitoring of carbon biomass, there is a lack of technical empowerment for the community members. Many environmentalists and Indigenous leaders and grassroots worry that "The governmental aspiration is to have title over biodiversity, water, and carbon with the intention to negotiate them in the international market whenerver it is possible" [7]p. 107.

The communities main power depends upon the decision of entering or not the PSB. However, they trapped in the interplay of autonomous, non-paid self-regulation hunting and logging and the opportunity to gain an income at the expenses of putting stricter regulations upon the usufruct of their ancestral forsts. The MAE holds the power and is backed by all the contract guidelines to terminate or sue the contract executors in case of non-compliance, but there are no stablished guidelines in the contract that empower the communities to do the same in case the MAE violates their rights. However, the communities are part of the CONFENAIE and they can use its political power to level the lack of protection in the PSB contract.

Recommendations

Some considerations for the Indigenous communities

Since the MAE and the Ecuadorian government are considering the potential of the areas under conservation to provide ecosystem service and carbon storage, and these components are not mentioned or negotiated in the SBP contract, it is necessary for the Indigenous communities, and their allies, to evaluate and plan strategies that will secure their rights over their territories and its usufruct. While there has been criticism about the burden put upon these Indigenous communities by the carbon market and REDD+ strategies, I suggest that they carefully come up with their own agenda and terms to engage in negotiations, so they can benefit economically as their main interest is also to preserve the forests for their own livelihood and life conservation.

Some cosiderations for the MAE

The social aspect of the PSB needs to be seriously reconsidered if they want to demonstrate their commitment with the poor sectors of Indigenous communities. Moreover, because there is no plan to monitor the effects that regulations upon traditional huntingg territories can have in neigbour forests, they have to implement planning strategies that will help level the side effects of the PSB on traditional livelihood and other non-protected forests.

Extra information

Here is a link to a video with some information about the benefits of the PSB for the A'i Kofán Indigenous community and the fundings sponsor, GM Chevrolet.

In this special report Ivonne Yánez, activist member of the NGO Acción Ecológica (Ecologic Action) and some Indigenous activists talk about the drawbacks of the PSB for Indigenous peoples and the commoditization of their 'home' for the sake of international corporations and developed countries. Unfortunately, there is no English subtitles for the Spanish dialogues. However, the interviews with Larry Lohman, memember of the Durban group for climate justice, are in English and provide some insights into the cautions needed to take about the PSB.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Krause, T., Collen, W., & Nicholas, K. (2013). Evaluating safeguards in a conservation incentive program: participation, consent, and benefit sharing in Indigenous communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Ecology and Society, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05733-180401

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Amazon Watch (2011). Ecuador’s forest partners program: An overview of Socio Bosque contract with Indigenous communities. Retrieved from http://amazonwatch.org/assets/files/2011-socio-bosque-executive-summary.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Krause, T., & Zambonino, H. (2013). More than just trees – animal species diversity and participatory forest monitoring in the Ecuadorian Amazon. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 9(3), 225–238.

- ↑ Krause, T., & Loft, L. (2013). Benefit distribution and equity in Ecuador’s Socio Bosque Program. Society & Natural Resources, 26(10), 1170–1184.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Podvin, K., J. (2013). Institutional analysis of the Socio Bosque Program: An Ecuadorian forest governance initiative and its interactions with REDD+ [Thesis]. Retrieved from http://edepot.wur.nl/256025

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Garzón, B., R. (2012). REDD en territorios Indigenas de la cuenca Amazónica: ¿Serán los pueblos Indigenas los directos beneficiarios? Brazil: ISA-EDF. Retrieved from https://www.socioambiental.org/banco_imagens/pdfs/reddamazoniafinal.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Acción Ecológica. (2012). Sobre REDD y el Programa Socio Bosque: REDD: Premio a la deforestación y usurpación masiva de territorios. Yachaykuna Saberes (14), 100-112. Retrieved from http://icci.nativeweb.org/yachaikuna/Yachaykuna14.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 de Koning, F., Aguiñaga, M., Bravo, M., Chiu, M., Lascano, M., Lozada, T., & Suarez, L. (2011). Bridging the gap between forest conservation and poverty alleviation: The Ecuadorian Socio Bosque program. Environmental Science and Policy, 14(5), 531-542. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2011.04.007

| This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST270. |