Course:FRST270/Wiki Projects/Munduruku Indigenous People versus forest concessions in the Tapajós region Para state Brazil

Munduruku Indigenous People versus forest concessions in the Tapajós region, Para state, Brazil

This case study reveals the conflicts between Munduruku indigenous peoples and Brazil federal government about a forest area in the Tapajos region, Para state, Brazil. Along the Tapajos river, Brazilian government was planning to build 43 hydropower dams, which would damage the rainforest ecosystem and flood the indigenous land lived by Munduruku peoples for centuries.[1] A series of documentations present how indigenous people and the authorities view the forest with different values, leading to the disagreements upon the decisions made. Ignorance on the petition of recognition of indigenous land and continuing the hydropower plans has prompted protest and violent repressions due to future destruction at Munduruku territory, where holds the history and cultural of Munduruku people. With the support of local ministry, Munduruku people stand up and defend their rights of the forests and forest from stakeholders that have economic interest towards the indigenous territories. This case study requires future monitoring since the conflicts started in 2012 and would be continue in the future.

Introduction

Loaction

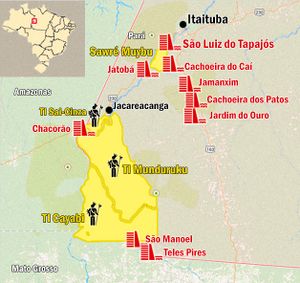

This case study is focused in Tapajos region, which located in between the states of Mato Grosso and Para within the Amazon rainforest zone, Brazil. The Tapajos river basin covers around 492,000 km2 of the Amazon. The biodiversity and geographic characteristic of Amazon rainforest is a natural history, as well as a cultural history. With more than 60,000 plant species, over 2,000 fish species, more than 300 species of mammals, 2.5 million species of arthropods and unknown numbers of microscopic organisms; so, the Amazon rainforest is the origin of natural resources for indigenous peoples. [2]

The Munduruku Peoples

Although there are non-indigenous people living in Tapajos basin, the major target to be discussed in this case study are the Munduruku peoples. The Munduruku indigenous people have been living in the Amazon region for thousands of years before the arrival and colonization of European.[3] The Munduruku culture and history are memorized and passed down to the next generation with their traditional knowledge of agriculture, their customary land and sacred sites at Tapajos basin. Although the population is separated into several groups, there are about 12,000 Munduruku Indians lived by the Tapajos river now. Living by the Tapajos river, Mundurukus rely on the natural products of Amazons to sustain livelihoods.[4]

Brazil’s São Luiz do Tapajós (SLT) Dams

Brazil plans to build 43 large hydropower dams in the Tapajos Basin along Tapajos river and its two branches, the Jurena river and Teles Pires river, turning the waterways into important industrial transportation pathways for transporting agricultural products, mostly soybean. According to Ten-year Energy Expansion Plan 2022, the state of Brazil is planning to have 10 of the large dams constructed.[1] Brazil’s federal government views the Tapajos chain as an opportunity for economic growth and poverty secession. However, the construction of SLT dams would bring negative impacts towards social and environmental aspects. The sizes of the dams are 729 km2, which is almost the same as the size of New York City. The construction would drive approximately 2,200 km2 of indirect deforestation, causing loss of aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity.[5] Therefore, the constructions would cause negative impacts to the Munduruku’s lifestyle including fishing and visit of sacred sites.

Tenure arrangements

Since 1960s, the government-instituted policies and projects are sought to develop Amazon in the aspects of infrastructure and economic activity. Logging and mining activities attracted many peoples into the forests for economic opportunities. However, the unclear regulatory environment and lack of restrictions when governing logging lead to a majority of illegal logging among total logging. Many investments in transportation are carried out without the permission from Ministry of Environment. [2]

1988 constitution guaranteed the rights of indigenous populations: right to be consulted before changes related to indigenous land happen. Also, the constitution pointed out that indigenous people have the right to the land that they are “traditionally occupy”.[6]

In 2014, the government started selling the forestry concession to private logging companies through auction. Forestry concession is a relatively new instrument in Brazil introduced by the federal government, and the recent concession is granted to logging companies without noticing the indigenous people. With the forestry concession, the companies can carry out logging activity in the national forests. [3]

In October 2014, the Munduruku Indians began a self-demarcation project. The Mundurukus decided to organize and go into the forests and carry out self-demarcation of the territory due to the delays in ensuring their land recognition. [6]

Administrative arrangements

The state of Brazil has week institutional environment and enforcement. Any project establishing in Brazil would go through an evaluation process of licensing, which estimates the damage and cost would cause. However, the stages of this legal process can be abbreviated by officials under political pressure because halting the project would cause severe damage to the "public economy". In the case of Munduruku, the Tapajos dams have greater importance of public economy comparing to protection of the environment and affected people in the perspective of Brazilian government. [6]

Prior License (licença prévia)

The licensing process in Brazil for a project like São Luiz do Tapajós (SLT) Dams proceeds through a series steps before making final decisions. First, the federal environmental agency, Brazilian institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) would receive the a “notification of intent” and be involved into the process. IBAMA would prepare terms of reference (ToR) that specify the requirements for further investigation called Environmental Impact Study (EIA). At the same time, The National Foundation for the Indian (FUNAI) would produce a ToR for the indigenous section of the EIA. EIA is usually done by a consulting firm which has a team with biologists, anthropologists and other as consultants to compose the report and a shorter version without technical information called RIMA (Report on Impacts on the Environment) for public distribution and discussion. After a series of public hearings (audiências públicas) and consultations is being held in the areas that would be affected, IBAMA and FUNAI would then request changes in EIA and RIMA. Finally, the prior license would be issued by IBAMA when the conditions are satisfied. [6]

Installation License (LI) and Operating License (LO)

After prior license is issued, the consultation firm would prepare a basic environmental plan (PBA) to propose mitigation measures and influences of affected communities. In this process, the PBA need to be revised to satisfy the requirements of IBAMA and FUNAI. Same as the prior license, the installation license would be issued upon the agreement of IBAMA; then, the constructions may begin. With all measurements in the PBA are determined to be implemented, IBAMA would issue an operating license (LO). [6]

Affected Stakeholders

The affected stakeholder in this case study is Munduruku Indigenous peoples who experience the most disruption contributed by the Tapajos dams project and waterway project and had their advices and protest ignored by the federal government. The long-period residence of Munduruku people positively contributes to Amazon rainforest's ecosystem with Amazonia dark earth, which is a new type of soil with rich nutrient.

The disruptions of the SLT dams toward the livelihood of the Munduruku will be population of displacement, loss of fisheries, loss of sacred sites, and other indirect effects. Also, the dams become a stumbling block in the process of indigenous land recognition. [1] There are two main objectives of Mundurukus are revealed in this case study:

1) Gainning official demarcation from Brazil federal government to reserve indigenous territories which will be critically affected by the Tapajos dams’ constructions. The formal recognitions need to be issued as soon as possible. [3]

2) Carrying out self-demarcation on indigenous lands to preserve the lands from further research contributing to Tapajos dams’ planning and logging activities by private companies with granted forest concession. The actions are carrying out by the Mundurukus since 2014. [6]

Unfortunately, the Munduruku communities have a relatively low power in decision-making process as the government ignored the voice of indigenous groups in “consultation” process regarding the Tapajos dams’ construction, and the protest of the Munduruku is controlled by national armed force.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

| Stakeholders | Main Relevant Objectives | Relative Power |

|---|---|---|

| Brazilian Government |

The state of Brazil is the highest authority in Brazil. Brazilian government has high level of power comparing to the other stakeholders as it is the final decision maker in the country. During the decision-making process of the SLT dams, coercion and violence are being abused to suppress the Munduruku's resistance movement (in 2012).[7] Violations are also exploited under the cover of security suspension to ensure the successful establishment of Tapajos dam and the waterway chained with the dams. Selling forestry concession to private logging companies is another objective of Brazilian state. [3] |

High |

| Public Federal Ministry (MPF) of Para State |

MPF is a public prosecutor's office established as the result of Brazil's 1988 constitution to defend the people against the trespass of their constitutional and legal rights. [6] In March 2015, MPF supports Munduruku and starts taking legal action, obtaining a series of injunctions against the dams as the construction is happening regardless of affected people's voice. In the same year, MPF pressured the federal government of Brazil for concluding the formal recognition of Sawre Muybu land (traditionally used by Mundurukus) [3] |

Relatively high |

| Greenpeace |

Greenpeace is an independent campaigning organization which joint with an Munduruku community in an unofficial demarcation in 2016. Greenpeace supported the Munduruku to save their land from the construction of Tapajos dams by calling on international companies to confirm they will not supply equipment and technicians to the project. [5] |

Low-Medium |

| Logging Companies | Gaining forest concession for logging | Low |

Discussion

Many development in Brazil trigger controversy between two different values of the Amazonia forest: production and protection. In the case of SLT dams, the conflict between the Munduruku peoples and the state of Brazil revolves around protection and production. There is no doubt that the reclamation of Amazon forest and building hydropower dams can bring economic development and enhance life quality of dwellers. However, this movement will bring no benefits but destructions to Munduruku peoples' home.

The sacred sites is significant in Munduruku's history and culture, which can be compared to the "heaven" in Christian. [7] The Munduruku concerned that the sacred sites would be damaged or flooded due to the construction of SLT dams because the sites are the places where Karosakaybu, a Munduruku ancestor with supernatural power, came down to the Earth and created the Tapajos River. One of the sites, the Sete Quedas holy site is the place where the spirits of old people rest after they died; and, the Mundurukus respect those people who have past away and believe they would bring happiness to this land. [6] After the "consultation" back in 2012, which the government of Brazil had ignored the results, Munduruku peoples started protesting at their community meetings. But, the consistent movement of the Munduruku Indians did not alter any changes in the Tapajos plan. In November 2012, a team of police with armed force carried out the Eldorado operation at Mongabay along the Teles Pires River, destroying barges for illegal gold mining in the indigenous land of Munduruku. [7] This operations was implemented without noticing Munduruku communities. When the villagers of Teler Pires village went to check out the situation, the police fired and caused 1 death and over 30 injuries of Mundurukus. Although the operation was said to combat the illegal mining activity, the violence was abused before communication with local indigenous. [7][4] This incident lead to critical damage on Munduruku peoples' properties and lives, as well as their relationship with the federal government. Mining to Munduruku peoples is a source of income; however, the mining history of Munduruku since the 18th century was ended in 2012. [7]

Assessment

The Munduruku Peoples

| Power/Rights | Yes/No |

|---|---|

| Access | Yes |

| Use the rights for subsistence | Yes |

| Use the right for sale | Yes |

| Management or co-management | No |

| Exclusion right | No |

| Alienation right | No |

The Munduruku Indians have lived and traditionally used the natural resources to maintain livelihoods at Tapajos river basin for a long time. After the establishment of Brazilian government, the indigenous people remain their access rights to their territories including their sacred sites. The crops and natural resources not only support Munduruku's daily subsistence, but also support their income. In 1964, the gold miner groups would stay at the working areas, which was inside the Amazon and away from the cities, for over 10 months. During the work term, the food resource of the gold miners was relied on natural products such as fishes, fruits and berries. Another reliable resource of food would be the Mundurukus; therefore, gold miners would purchase manioc flour, bananas and fresh meat from the Munduruku villages.[8]

State of Brazil

The government of Brazil is the initial and final decision-making legislative group in the case of SLT dams. To overturn injunctions negating the Tapajos River dams, the government of Brazil successfully defended the plan with "security suspension".[1] The state also sell forestry concession in the national forests to private logging companies in order to intimidate the Munduruku and suppress their protesting in the future. [3]

Public Federal Ministry (MPF)

The MPF of Para, the targeted location of this case study, supports the Munduruku and forced IBAMA to carry out consultation specified in ILO-196 before granting license to SLT dam project at the Regional Federal Court in June 2015. [6] This was the call for tender missed the information about indigenous and non-indigenous families and archaeological sites in the research areas. Another point of the call for tender was the formal recognition for indigenous land, Sawre Muybu, which is traditionally occupied by the Munduruku peoples. [3]

Recommendations

The story of Munduruku people struggling to against the state of Brazil is continuing until now and will be go on in the future. This case study reveals the struggle of a country facing development opportunities. Conservation can save the indigenous people's belief, culture and history, whereas the selection of production can save the others from poverty. Indigenous would have much more difficulties to protect their land because they are minority in the total population. For Munduruku peoples, the lack in indigenous identity of land definitely increase the level of difficulties to reserve their land from a business plan with enormous economic potentials.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Fearnside, P. M. (2015). Amazon dams and waterways: Brazil’s Tapajós Basin plans. Ambio, 44(5), 426-439. doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0642-z

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lele, U. J. (2000). Brazil: Forests in the balance: Challenges of conservation with development. World Bank Publications.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 World Rainforest Movement. The Mundukuru peoples in Brazil: forestry concessions imposed on indigenous lands. (2015, September 15). Retrieved November 01, 2017, from http://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section1/the-mundukuru-peoples-in-brazil-forestry-concessions-imposed-on-indigenous-lands/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Munduruku: Weaving Resistance. (2014). Retrieved November 01, 2017, from https://vimeo.com/112230009

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Newsroom. (2016, June 19). Brazil’s Munduruku Indians Start a Movement to Save an Amazon Tributary. Brazzil. Retrieved from http://brazzil.com/23955-brazil-s-munduruku-indians-start-a-movement-to-save-an-amazon-tributary/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Fearnside, P. M. (2015). Brazil’s São Luiz do Tapajós Dam: The Art of Cosmetic Environmental Impact Assessments. Water Alternatives 8(3): 373-396

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Branford. S., Torres. M., (2017, February 05). Brazil: The Day the Munduruku Found Out the Police Were Not Their Friend. Brazzil. Retrieved from http://brazzil.com/brazil-the-day-the-munduruku-found-out-the-police-were-not-their-friend/

- ↑ Sheffler, E. M., & Southwick, E. E. (1984). Environmental resource management on the Munduruku savanna. Environmental Management, 8(3), 215-220. doi:10.1007/bf01866963 Because the land of Munduruku villages are managed with de jure policies, the Munduruku Indians are not eligible to make decisions, exclude anyone from the land and sell the land.

Branford. S., Torres. M., (2017, February 05). Brazil: The Day the Munduruku Found Out the Police Were Not Their Friend. Brazzil. Retrieved from http://brazzil.com/brazil-the-day-the-munduruku-found-out-the-police-were-not-their-friend/

Fearnside, P. M. (2015). Amazon dams and waterways: Brazil’s Tapajós Basin plans. Ambio, 44(5), 426-439. doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0642-z

Fearnside, P. M. (2015). Brazil’s São Luiz do Tapajós Dam: The Art of Cosmetic Environmental Impact Assessments. Water Alternatives 8(3): 373-396

Lele, U. J. (2000). Brazil: Forests in the balance: Challenges of conservation with development. World Bank Publications.

Newsroom. (2016, June 19). Brazil’s Munduruku Indians Start a Movement to Save an Amazon Tributary. Brazzil. Retrieved from http://brazzil.com/23955-brazil-s-munduruku-indians-start-a-movement-to-save-an-amazon-tributary/

Sheffler, E. M., & Southwick, E. E. (1984). Environmental resource management on the Munduruku savanna. Environmental Management, 8(3), 215-220. doi:10.1007/bf01866963

Munduruku: Weaving Resistance. (2014). Retrieved November 01, 2017, from https://vimeo.com/112230009

Wildlife Conservation Society. Tapajós. (n.d.). Retrieved November 01, 2017, from http://amazonwaters.org/basins/great-sub-basins/tapajos/

World Rainforest Movement. The Mundukuru peoples in Brazil: forestry concessions imposed on indigenous lands. (2015, September 15). Retrieved November 01, 2017, from http://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section1/the-mundukuru-peoples-in-brazil-forestry-concessions-imposed-on-indigenous-lands/

| This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST270. |