Course:FRST270/Wiki Projects/Community Forests in the Cordillera region of The Philippines

Community Forests in the Cordillera region of The Philippines

Description

The Cordillera region of the Northern Philippines contains a vast landscape of mixed tropical montane forests. [1] Amongst these dense forests are scattered plots of agricultural land, exhibited by extravagant terraced landscapes. [1]These terraced landscapes are used to keep the crops inundated with water year-round, which is especially important during the dry season when a lack of rain starts to dry up the soil. [2] The most prominent human society in this region is known as Ifugao. The Ifugao people depend on the forest products for subsistence, as well as economic competition. [2] The Natives of Ifugao have an age-old practice of shifting cultivation of different crops such as sweet potatoes, or rice. The shifting cultivation method involves cycling crops from different locations and to newer areas in order to make use of the best possible growing conditions; plots of land that have recently been used to cultivate a crop are abandoned in order to regrow to their original state. [3] In a case study of the Hanunóo people, Harold C. Conklin [1] observed as many as fifteen different phases of plant cycling on specific plots of lands. A very common practice in shifting cultivation is harvesting a certain crop or forest product, then setting fire to the area in order to return it to an optimal condition for regrowth, this is known as “slash-and-burn”. [4]While slash-and-burn techniques have been shown throughout centuries of history to operate sustainably, more recent increases in demand for crop production due to a rapidly increasing global population have made the practice sustainable no longer. [5]

Colonization of the Philippines

The Philippines were colonized by the Spanish Empire in the mid 1500’s, however, colonial effects on forests did not truly begin until about the mid 1800’s when the state declared rights over forest use and access.[6] In 1889, slash-and-burn cultivation, also known as kaingin, was outlawed in the Cordillera region, and in 1901, a law made it so that forest occupants who practiced kaingin, kaingineros, were evicted from the forests.[6] Since the use of slash-and-burn was a key component of many of the indigenous people in the Cordillera region, these laws presented many problems. The Native people were forced to either change their ways of agriculture, resulting in lower crop yields and less overall production, or risk being evicted from their native lands by practicing a process they have been using for centuries before. In an effort to try to appeal to the demands of the local communities of indigenous people in Cordillera, the State created the Forest Law of 1917, which established communal forests that were completely under state control. [6] In 1941, a ‘Revised Communal Forestry Regulation’ was created in order to give more rights to people within communities; this order “granted the privilege to cut, collect, and remove… forest products for their personal use.” [6]

Community Forest Policies: Post-Colonization Era

During the 1970’s true community forestry started to take root in the Cordillera region. With the Native peoples’ dependence on kaingin in mind, the government implemented the Kaingin Management and Land Settlement Regulations, which allowed for kaingineros to continue with their slash and burn techniques given that they also practice soil conservation and tree farming in specified areas. [6] In 1976, the Forest Occupancy Management Program was created, granting tenure arrangements in the form of two-year renewable occupancy permits to kaingineros. [6] A few years later, in 1979, the Communal Tree Farming Program was created, creating large governmental investments in reforestation, as well as declaring that all cities or municipalities in the Philippines must begin establishing tree farms. [6] The next form of tenure arrangement came in 1982, when the Integrated Social Forestry Program was created, granting rights to occupy and develop forests to members of the program for 25 year periods. [6] ) One of the largest breakthroughs in Indigenous rights came in 1993 with the Delination of Ancestral Lands and Domain Claims Administrative Order. This order came from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), creating specific task forces whom were required to identify ancestral land claims of Indigenous communities. [6] Once these areas were delineated, the respective indigenous communities gain ‘Certificates of Ancestral Domain Claims’. (DENR Administrative Order No. 2) The Indigenous People’s Rights Act in 1997 expanded on this by requiring the State to protect the rights granted in the DENR Administrative Order No. 2, in order to protect the communities’ well-being. (Republic Act No. 8371) The first implementation of Community Based Forest Management (CBFM) in the Philippines happened in 1995 with Executive Order No. 263. [6] The goal set out by the State was to have all participating members in a forest follow a certain set of environmentally and socially conscious rules to ensure sustainable forest management (Executive Order No. 263) Indigenous rights were later enhanced under CBFM when the Manual of Procedures on Devolved and Other Forest Management Functions Joint Memorandum Circular No. 98-01 was passed in order to grant rights that were previously held by the DENR to local government units. [6]

Tenure Arrangements

Tenure: Defined

The FAO defines Tenure as “the relationship, whether legally or customarily defined, among people, as individuals or groups, with respect to land.” [7] While this one sentence definition seems simple on the surface, it has many layers to it, as well as many implications globally, and within the community forestry world. To start, tenure arrangements can be written in to law, or defined customarily. Many indigenous communities around the world have what is perceived to be customarily defined tenure arrangements. Customary tenure arrangements or customary rights in general have been “accepted” and known for a long period of time, they are normally not written down, and their perceived value in modern times is seen as ‘not legal’ or ‘de facto’. [7] Tenure arrangements are, generally, categorized in four ways: Private, Communal, Open Access, or State.[7] Private lands are owned by a private party (individual, group of people, or corporation).[7] Communal lands are owned by a community, in which each member has a certain amount of rights over the land.[7] Open access means that no rights are specifically given to any one person, and nobody can be excluded from using the land.[7] State ownership means that the government has the rights to the land.[7]

Tenure in the Cordillera

Native communities in the Cordillera region of the Philippines have long held customary tenure arrangements over their land.[2] These arrangements required no need for bureaucratic decisions, because they were fueled by need, and each of the lands were managed in a private manner.[2] The Ifugao’s were also able to transfer the rights of their lands by inheritance or by sale, commonly known as transfer rights.[8]

Once colonization of the Philippines began, the age-old customary rights of the Ifugao’s began to diminish. With a centrally controlled government putting pressure on the natural resources in Cordillera, the need for legal tenure came in to play. During the 1800’s, farmers in the Cordillera region were being persecuted and evicted from their customarily owned land by State.[6] Without any legal access to the land granted by the government, the displaced farmers no longer had any reason to garner forest products in a sustainable manner.[9] The interruption of the local communities’ rights to their land instigated a commonly seen problem: the lands being treated as open access.[6] The practice of open access resulted in mass deforestation happening all around the Cordillera region. [6]

After many years, the implementation of Community Based Forest Management in the Cordillera region acted as a balance between the government and the local communities.[9] CBFM created tenure arrangements for the indigenous peoples in the Cordillera region, effectively eliminating the treatment of the land as open access.[9] The implementation of CBFM also grants many rights to the local communities, including access, use, management, and exclusion rights.[9] CBFM in the Philippines has two types of tenure arrangement, a CBFM agreement, and a certificate of stewardship.[6] A CBFM agreement is an agreement between the government and a local community that provides a 25-year term of ownership, and is renewable for another 25 years afterwards.[6] A certificate of stewardship is granted to a private owner of land that falls under a CBFM agreement.[6] The certificate of stewardship is a legally defined version of ownership, but allows private owners to manage the land that they own in a way similar to their ancestors.

While the promises of the CBFM program in the Philippines show an effort to give rights back to the local communities in the Cordillera region, a case study by Pulhin et al (2008)[10] shows that the DENR still remains in control of much of the use, management, and exclusion rights of the forests in the Cordillera.

Administrative arrangements

Although the objective of CBFM is to devolve rights to Cordillera forests to the various stakeholders involved, the DENR is the only stakeholder with the legal right to issue land tenures.[6] Granting the rights of assigning tenure to the DENR came about in the DENR order No. 2004-29, and ensures that the highest and possibly only effective administrative arrangement in the CBFM program is made by the DENR.[6]

Within a CBFM agreement there are three categories of stakeholders. The first and most simple category would be the local community, comprised of people who use the forest for economic profit, or subsistence, but have little to no say in managerial decisions on the forest.[6] People within the local community have access and use rights. The secondary category exists within the local community members: they are special participants of what is known as the People’s Organizations. People’s Organizations exist in each community that falls under CBFM within the Cordillera.[6] While Peoples Organizations vary across communities, they are all governed by a Constitution and By-Laws that determine the roles of People’s Organization Officers/Members and outline the rules of the forests.[6] The Officers and Members of a People’s Organization are selected under regulations implemented by the DENR. These regulations state that the members of an Organization must be Filipino citizens, own land that falls under a CBFM agreement, use the land for a “substantial portion” of their livelihood, and live within the region of the land.[6]

Although the DENR controls administration of most of the CBFM designated forests, not all forestlands in the region fall under the CBFM arrangement. All forests in the region have been designated as CBFM unless they fall under the following four categories outlined by Juan M. Pulhin (2005).[6]

- Areas covered by existing prior rights except when the lessee, permit or agreement holder executes a waiver in favor of the People’s Organization applying for the CBFM Agreement. Upon termination of any pre-existing permit for non-timber forest products however, the permit shall not be renewed and any new permit shall be given to the Community-Based Forest Management Agreement holder.

- Protected areas as mandated in Republic Act 7586 (National Integrated Protected Area Systems or NIPAS Law) and the implementing rules and regulations.

- Forest lands which have been assigned by law under the administration and control of other government agencies, except upon written consent of the government agency concerned.

- National Council for Indigenous Peoples certified ancestral lands and domains, except when the Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples opt to participate in CBFM.

In the case of category 3, the government is the sole administrator of the land, while in the other three categories, the lands are administrated by a private owner.[6]

Affected Stakeholders

Within a community forest, the affected stakeholders are stakeholders whose livelihood is dependent on their rights to the forest. The only truly affected stakeholders in the Cordillera region are the local indigenous peoples such as the Ifugao. The Ifugao are affected because their sources of subsistence as well as wealth are all generated from the forests they live in.[2] Due to colonization and the stripping of rights from local communities, the Ifugao people struggled to maintain their livelihoods from the forests as they had for centuries before. In accordance with the DENR Order No. 2004-29, implemented in 2004, the Forest Management Bureau was created.[6] The Forest Management Bureau is a sector of the DENR tasked specifically to deal with the implementation, oversight, and management of CBFM.[6] Since the Forest Management Bureau deals only with CBFM related tasks, and would not exist without CBFM, the Forest Management Bureau could be considered an affected stakeholder. However, the members of Forest Management Bureau are not necessarily as affected as the local communities because they are government employees, and they have easier access to alternative sources of income streams when compared to local indigenous peoples.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

The Interested Stakeholders in a community forest are the people who have vested interest in the livelihood and products of the forest, usually for personal economic gain, but their livelihoods are not solely dependent on rights to the forest. The most prominent interested stakeholder within CBFM in the Cordillera Region of the Philippines is the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, or DENR. [9] The DENR is a government body that is the main agency responsible for managing the nations forestlands.[6] The main interest of the DENR is to appeal to the needs of the local people in the Cordillera, while also maintaining the economic inputs of the forest to the Philippine Nation. The DENR also has three subdivisions, all of which are considered to be interested stakeholders: The Regional Environmental and Natural Resources Office, the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office, and the Community Environment and Natural Resources Office.[6] An argument could be made that the Community Environment and Natural Resources office is technically an affected stakeholder, because it holds the values of the affected stakeholders. However, since the employees of the Community Environment and Natural Resources Office are employed by the central government, they are mostly interested stakeholders.

Smaller, but equally important in CBFM in the Philippines, is the stakeholder group of independent corporations, such as a logging company. Forest companies depend on timber products in order to receive economic gain, but their ability to obtain these products is not entirely location based; they do not require ownership of the specific forests in Cordillera in order to sustain themselves.[11] Since an independent corporation is not fully dependent on their rights to a forest area, independent corporations are considered interested stakeholders.

Discussion

Summary

Community Based Forest Management in the Philippines is an essential instrument to maintain order and equality amongst stakeholders within the forest of the Cordillera region. The slow but effective implementation of its facets has shown not only the pressing need for it in order to both sustain the forests and the livelihoods of the local indigenous communities, but the diligence of the government to try to repair the damage they inflicted during colonization. Before the implementation of CBFM, the local communities in the Cordillera were struggling to sustain themselves, and the forests in the region were being degraded at an alarming rate.[12]Treatment of the forest as open access, as well as a massive amount of slash-and-burn being used to try to meet increased demand for forest products would have brought demise to the natural resources in the region if nothing was done.[12] The CBFM program, which contains clearly outlined sustainability initiatives, provided a basic solution to all of the stakeholders in the Cordillera forests, including both the Filipino government and the local Indigenous Communities.[12]

Stakeholders

Filipino Government

The Filipino Government is in charge of managing the interests of all the stakeholders within the forest, as well as managing important economic resources to further develop the economy and country.[12] The government also has the largest amount of power in the Cordillera forests, they have complete control to promote or remove the power of each of the stakeholders. Simply put, the interest of the government is to maintain equality amongst stakeholders in the most efficient and economically effective manner.

Local Communities

The Local Communities receive arguably the most impact from decisions about the forests they live in, while also remaining under the thumb of the larger, more economically powerful institutions above them. While the rights that they contain are legal, and granted to them by the Government, these communities are small and have little economic power, and but could easily have their rights taken away. The implementation of CBFM gave the indigenous communities of the Cordillera what is known as a bundle of rights, containing access, use, transfer, and exclusion rights.[9] From the point of view of local communities, however, the current system stands to be improved, for example, by granting them managerial power of CBFM.[9] Simply put, the interest of a Local Community is to sustain their livelihoods, however, their lack of economic influence and power make it difficult for Local Communities to achieve such interests.

Independent Corporations

Independent Corporations are arguably the least impacted stakeholders operating within a CBFM. Their interest in the forests are usually entirely economically based. However, since they are independent of the forest themselves, they are available to seek out and obtain alternative income streams. Independent Corporations contain a strong managerial impact because they have economic power, which gives them the ability to influence decision makers.[9] Simply put, the interest of Independent Corporations is economic gain.

Assessment

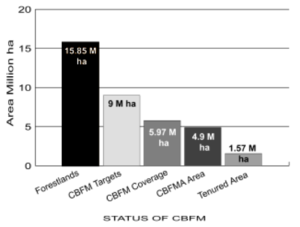

The implementation of CBFM in the Philippines has had many impacts on the forests in Cordillera. A case study of the effects of CBFM by Juan M. Pulhin et al. (2008)[10] has shown that CBFM improves forest regrowth, forest cover, and overall sustainability of forests within the regions of implementation. Within the 15.85 million hectares of forests in the Philippines, nine million hectares fall under CBFM targets.[13] Of those nine million hectares, 5.97 million hectares contain CBFM coverage, 4.9 million have a CBFM agreement, and 1.57 million is tenured (privately).

[13] In a study by Guiang et al. (2001)[14] the implementation of CBFM has been shown to shown to improve the health of the environment due to improved soil fertility, water supplies, and microclimates. In the same report, Guiang et al. (2001)[14] emphasizes that there is much more room for further improvement of the CBFM in order to create a more sustainable community of use of these forests.

The current CBFM system in the Philippines has many areas of improvement. Juan M. Pulhin (2005)[6] states acknowledge the existence of economic disparity within local communities as well as government actors within the CBFM program. While in some areas of CBFM the local communities and People’s Organizations have seen drastic changes in economic power, most areas have seen little to no change.[6] A common issue seen in Community Forestry agreements is Environmental Job Blackmail, where local communities are forced to accept sums of money in return for allowing corporations to degrade their environment, or forests. Pressure to engage in Environmental Job Blackmail is being seen more and more as corporations are subjected to stricter policies under CBFM.[6]

Recommendations

According to multiple studies, such as Pulhin et al. (2008)[10], Guiang et al. (2001)[14], and the Forest Management Bureau[13], the implementation of CBFM in the Philippines has been relatively effective. As it appears, there is sufficient evidence that the Filipino government, alongside the DENR, is making strong efforts to promote sustainability within the forest as well as assist all stakeholders in remaining equal with each other on their rights to the forests. However, what has also been shown is that there are many inefficiencies within the CBFM program, such as the fact that the DENR still maintains most or all of the decision-making power, or that there are many local communities who have gained nothing economically since the implementation of CBFM.

One of the most prominent researchers of the Philippines CBFM program, Juan M. Pulhin, has many recommendations on how to improve the programs function. Pulhin states that in order to properly implement CBFM, the government needs to take more notice of the pre-existing management systems that have worked for many centuries prior for the indigenous peoples of the Philippines.[6] He also mentions that while the objectives of the CBFM program are very on track with success, the institutions and governing practices are not set up to properly manage CBFM.[6] Much of the funding for the CBFM program is currently externally sourced, due to the inefficiencies within, causing it to be very economically strenuous. However, with proper implementation of policy reforms, the CBFM program in the Philippines could become much more economically sustainable.[6]

Personal recommendations

Personally, I believe there are a couple steps that need to be taken in order to further the impact of CBFM in the Philippines. The first step would be to increase the decision-making power of the Local Communities in Cordillera. The reason there is a problem with environmental job blackmail in CBFM forests is because the economic benefits of selling the right to deplete the forest resources are higher than the economic benefits provided by CBFM. This shows that the CBFM model is not providing enough for the local communities to keep even them from degrading their own forests. However, providing enough decision-making power to the local communities to bring them to the point where they are able to say no to environmental job blackmail will not only help the local communities, but will also aid in achieving, or completely achieve, the initial sustainability goals set out by the CBFM program. The second step would be to create proper incentives for those who lose as a result of CBFM implementation. For example, if a foresting company begins to lose profits due to inaccessibility to CBFM forests, they should be compensated by the government on the money that they lose, or at least be given other alternatives to make up for their losses.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Conklin, H. C. [1957]1975. Hanunóo agriculture: A report on an integral system of shifting cultivation in the Philippines. Reprint. Northford (CT.): Elliot’s Books. De Schlippe, P. 1956. Shifting Cultivation in Africa. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Conklin, H. C. 1980. Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao: A Study of Environment, Culture, and Society in Northern Luzon. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Barker, T. C. (1984). Shifting cultivation among the Ikalahans. Working Paper, Series 1. College, Laguna, Philippines: Program on Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines at Los Banos College.

- ↑ Waters, Tony (2007). The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 3.

- ↑ Kettler, J.S. Agroforest Syst (1996) 35: 165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00122777

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 6.31 6.32 6.33 6.34 Pulhin, J. M. (2005). Community Forestry in the Philippines.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). What is Land Tenure? http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/y4307e/y4307e05.htm

- ↑ Barton, R. F. Ifugao Law. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Rebugio, L. L., Carandang, A. P., Dizon, J. T., Pulhin, J. M., Camacho, L. D., Lee, D. K., & Peralta, E. O. (n.d.). 2008 Promoting Sustainable Forest Management through Community Forestry in the Philippines. Forests and Society - Responding to Global Drivers of Change, 355-368.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Pulhin, J.M., Dizon, J.T., Cruz, R.V.O., Gevaña, D.T. & Dahal, G.R. 2008. Tenure Reform on Philippine Forest Lands: As- sessment of Socio-economic and Environmental Impacts. College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines, Los Baños Philippines. 111 p.

- ↑ Ganzon, F. G. (2006). Sustainable Forest Management of Benguet Pine in the Cordillera, Philippines.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Tyler, S. R. (2006). Communities, livelihoods and natural resources: action research and policy change in Asia. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. Cordillera of the Northern Philippines, 231-252

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Forest Management Bureau. 2004. Community-Based Forest Management: A National Strategy to Promote Sustainable Forest Management (Background Information.) A briefing material presented during the meeting of the National Forest Program (NFP) Facility Coordinator based at FAO Bangkok and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Undersecretary for Field Operations on November 17, 2004 at Forest Management Bureau Conference Room, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Quezon City.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Guiang E., S. Borlagdan and J. Pulhin. 2001. Community-Based Forest Management in the Philippines: A Preliminary Assessment. Project Report. Quezon City: Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University

| This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST270. |