Course:FNH200/2012w Team05 Tofu

Introduction

Tofu is an edible Asian commodity created by coagulating the soy milk that is produced through harvesting and boiling soy beans. In the west, tofu is also known as “bean curd” or “soya curd” [1][2]. Tofu can be made to have different levels of firmness, which can range from the custard-like texture of looser tofu, or the soft, cheese-like structure of firm tofu. This modifiable property of tofu allows it to have a wide variety of culinary applications. For example, soft/looser tofu that is difficult to pick up is commonly consumed as dessert, while firmer tofu that is able to retain its shape is used in stir-fry dishes[3].

Initial Thoughts

Although its roots are from Asia, tofu has grown and developed into a food that is consumed as a part of their daily diet by many North Americans. Due to its high nutritional content (see 'Health Benefits and Nutrition' below for more information), it can provide an alternative source of proteins for vegetarians, as well as provide a well balanced diet for many [4]. Due to its emergence as a popular food, we are interested in examining the differences between the traditional method and the commercialized method of tofu production. Before extensive research is conducted, some of the following questions may arise:

1) What are the key differences between traditional and commercial tofu production?

2) Do these differences enhance or inhibit the quality or flavour of the tofu? If so, in what way and by what mechanisms does this occur?

3) Are there extra ingredients or additives in one of the methods? What do these extra ingredients/additives do?

4) Does the nutritional value change between tofu made traditionally, and tofu made in a commercial factory?

5) Based on the information given, which difference in the quality of the tofu would most likely effect the choice for the majority of the consumers?

Throughout this project, we aim to answer these questions by examining and presenting information to readers, such that the next time they purchase tofu, a more informative choice can be made by the individual.

History

The use and consumption of tofu was first documented in China over 2000 years ago on stone tablets, which depicted the process of making tofu with the use of soy milk and soy beans. Tofu has been such a staple food in China that it is mentioned as early as 1500 AD in a poem titled “Ode to Tofu”[5].

Tofu was then spread to Japan when monks, who ventured to China to study Buddhism, brought back tofu from China in the 700’s. It was adapted into a part of the Japanese diet in the late 1400s. Tofu then spread to the Western world in the early 1600’s[6].

Tofu is now one of the most popular soy foods in the United States, along with soy milk, soy sauce, miso and tempeh. The acceptance and utilization of tofu by the western civilization has also led to many derivatives of tofu, including tofu hot dogs and tofu ice cream[7].

Different Types of Tofu

Although all tofu is made from natural coagulants, the texture and consistency of the tofu can be dependent on the amounts of water and coagulant used. Textures include extra-firm, firm, and soft/silken. Manufacturers may also make tofu flavoured, such as adding hints of jalapeño, caramel and coconut, since plain tofu has little or no taste [8]. Tofu can be labelled as either Fresh or Processed Tofu [9].

Fresh Tofu

Extra Firm and firm tofu

Fresh Tofu is the tofu that is produced directly from soy milk. As one can imagine, extra-firm tofu correlates to lower amounts of moisture. Extra firm tofu and firm tofu have textures that are comparable to that of cooked meat and raw meat respectively. Dues to its rigidity, the two are most appropriate for stir-fry dishes, soups and grilling, since it will easily retain its shape [3].

Soft and Silken Tofu

Soft and Silken tofu are tofu that are undrained and unpressed. They have the highest moisture content of all fresh tofus. Their texture is smooth and silky. Due to the high moisture content, soft and silken tofu are more fragile than firmer types [12]. Because of this, soft and silken tofu is often blended into sauces, dessert, drinks, and even used to replace milk and eggs in baked goods [13]. Silken tofu is often packaged in antiseptic boxes. This process involves packaging the tofu above the pasteurization temperature, which greatly extends its shelf life (when unopened) to an entire year, even without refrigeration [10] [12].

Processed Tofu

Processed tofus are products that are derivatives of fresh tofu, which add to the variety of soy bean products. Processed tofu has often undergone more treatments, which give it a longer shelf life, as well as different flavours and textures[9].

Fermented Tofu

This type of fermentation changes the flavour and texture of the tofu, but not its preservation. In this type of tofu, it is cut into cubes and inoculated with bacterial spores that cause fermentation . The tofu is then allowed to dry, and placed in a brine made of rice, wine, salt along with other spices and kept in the brine for a certain amount of time (usually ~2-6 months, but may vary depending on the desired end product) [15]. Similar to cheese, a longer aging process generally produces a better product. Fermented tofu gives a soft, almost creamy texture. The brine in which the tofu is submersed often gives the tofu a distinct and characteristic flavour [1].

Flavoured Tofu

Flavoured tofu is often made by adding additional flavours into the soy milk mixture, before the coagulating agent is added. Some flavours even include fruits, such as mango and coconut [8]. This not only enhances the tofu's flavour, but can also affect texture. For example, egg flavored tofu adds egg flavour and yellow colour, but also provides fuller and richer texture to the already silken tofu (see image to the right).

Fried and Frozen Tofu

Tofu can be fried or deep fried to produce tofu puffs. If dehydrated, these puffs can have an extended shelf life. Tofu can also be frozen, which allows for large ice crystals to develop inside the tofu, forming large cavities. Freezing tofu can also be a method of preservation to extend shelf life. Both forms of tofu are commonly used in cooking and in hot-pot[3].

Health and Nutrition

Health Benefits

Tofu is high in protein, B-vitamins and calcium, while low in cholesterol, calories and fat content [2][17]. Because of its high protein content, it is commonly used as an alternative to meat by vegetarians [4]. Studies have also shown that it may provide more health benefits than meat in general. Although the energy and carbohydrate contents are roughly similar between meat and tofu, those who integrate tofu into their diet have shown significantly lower cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as well as lower levels of high and low density lipoproteins (HDL’s and LDL’s) [18][19]. This reduces oxidation of low density lipoproteins (LDL’s), which lower the risk of coronary heart disease [20].

Increased frequency in the consumption of tofu has also been shown to decrease the risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans[21]. Health Canada has approved tofu to be an appropriate substitute for meat, where 150 grams, 175 mL or ¾ cup of tofu can replace 75 grams, 125 mL or ½ cup of lean meat of poultry[22]. The following comparisons between tofu and other foods can be seen below [19][23][24]:

| Tofu | Ground beef | Fish | 2% Milk | Cheddar Cheese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calories (per half cup/4 oz serving) | 94 calories | 331 calories | 96 calories | 60 calories | 320 calories |

| Protein Content (per 100 calorie serving) | 11 grams | 8.9 grams | 21 grams | 4 grams | 6.2 grams |

| Fat Content (per half cup serving) | 5 grams | 15 grams | 1 gram | 2.5 grams | 5.5 grams |

| Cholesterol Content (per half cup serving) | None; it is cholesterol free because it is plant based | 113 milligrams | 67 milligrams | 9 milligrams | 30 milligrams[25] |

A half cup of tofu contains approximately 227 mg of calcium, which is approximately 22% of the recommended daily intake (for an average middle-aged man), as well as 1.82mg of iron (The calcium and iron content may vary depending on the water content of the tofu)[23]. The high calcium content is effective in delaying the onset of osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis [26].

Tofu has been ineffective in helping women alleviate symptoms that occur during menopause, due to the presence of phytoestrogens in tofu. These molecules (the isoflavones in particular) can have weak interactions with estrogen receptors and mimic the function of estrogen [27]. During menopause, the isoflavone levels from tofu may stabilize the fluctuating levels of estrogen in women. As such, this stability in estrogen levels can reduce and even prevent several symptoms, such as hot flashes [28].

Health Risks

Although there are significant benefits of tofu, a common health risk associated with it is that it is a common allergen. The United States Center for Disease Control has noted that soy foods are one of the top 8 food allergens affecting North Americans [29]. If an individual, unbeknownst to the presence of such an allergen, were to ingest soy products such as tofu, they may suffer from a range of symptoms. This may range from small itches, rashes and swelling of the tongue, to difficulty breathing and chronic bowel problems [29].

Tofu, similar to many other soy foods, contain oxalate molecules. Although oxalate is associated with contributing small amounts of calcium to one's diet, a build-up of excess oxalate in body fluids can lead to the formation of oxalate crystals [29]. These crystals have the potential to cause major kidney or gallbladder toxicity. If the build-up continues to increase, an individual may eventually suffer from advanced renal failure. [30].

Like all food products, the presence of harmful microorganisms in tofu is a concern. The United States CDC has documented cases in which traces of Clostridium botulinum have been found in self-fermented tofu [31]. Although this may be a concern to consumers, there are always precautions, such as the use of nitrites, that are taken in order to eliminate the presence of these microorganisms [32].

Ingredients

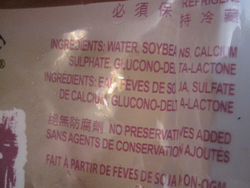

When making tofu, the main ingredients are soybeans, water and coagulant/curdling agents[17]. The coagulant is used to coagulate the soymilk produced from soaking and grinding soybeans, as well as to mold the resulting curds. The traditional Japanese coagulant used is a white powder called nigari, which is made from evaporated seawater along with the removal of sodium chloride[33]. In commercial production settings, the coagulants can be salts, such as Calcium Sulphate (CaSO4), Magnesium Chloride (MgCl2) or Calcium Chloride (CaCl2), as well as acids, such as Glucono Delta-Lactone (C6H10O6) [34][33][35]. Enzymes (specifically proteases from plants such as papaya) can also be used as coagulants, though they have not been commercially approved [34].

The amount of coagulant added will undoubtedly affect the curdling of the tofu[9]. Water is often added in order to initiate the activity of the coagulant. The amount of coagulant added, as well as the water content of the tofu can also affect the consistency, texture and flavour of the final product[36]. To help with coagulation, more than one type of coagulant may be used. As the picture to the left depicts, both Calcium Sulphate and Glucono Delta-Lactone are used in the production of Tofu.

The type of coagulant will also affect the tofu product. Calcium Sulphate and Glucono Delta-lactone are used by producers when making a smoother, softer tofu with higher water content, while Magnesium Chloride is used when making a firmer, more compact type of tofu. When compared to the traditional Japanese coagulant nigari, the commercial methods often also yield smoother curdling and in higher volumes, which often make it a more economical choice[9].

As seen below, the type of coagulant used can also affect the nutritional value of the resulting tofu. The nutritional values below correspond to a 100g serving of tofu.

| Extra Firm Tofu (with Nigari) [37] | Firm Tofu (with Nigari) [38] | Firm Tofu (with Calcium Sulphate)[39] | Regular Tofu (with Calcium Sulphate)[40] | Firm Tofu (with Nigari, Calcium Sulphate and Magnesium Chloride)[41] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calories (Cal) | 91 | 146 | 145 | 76 | 70 |

| Carbs (g) | 2 | 4.39 | 4.28 | 1.88 | 1.69 |

| Fat (g) | 5.83 | 9.99 | 8.72 | 4.78 | 4.17 |

| Protein (g) | 9.89 | 12.68 | 15.78 | 8.08 | 8.19 |

The coagulants used undoubtedly affect the characteristics of the tofu, and can therefore be classified as a food additive [32]. However, the incorporation of these additives into tofu has been approved by Health Canada [42] and is therefore safe to consumers.

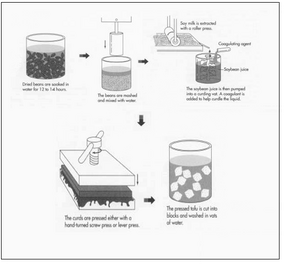

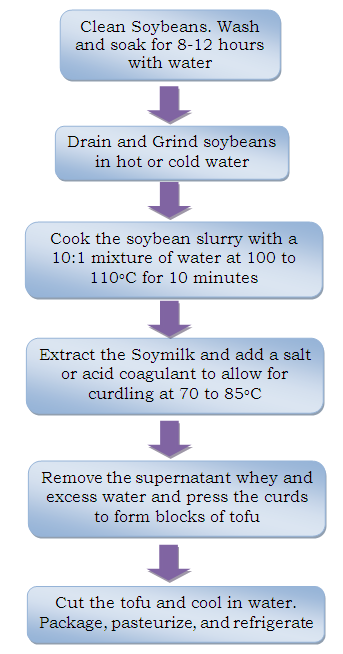

Traditional Method of Tofu Production

In China, soy bean is considered as one of the Five Sacred Grains. The generally steps of making tofu involve picking, soaking, blending and cooking soy beans, and then separating the soy bean pulp from the soy milk. A coagulant is then added to the soy milk to allow it to curdle, before cutting it into solid blocks [17].

Soy beans were picked by hand in the fall, in a time period usually from October until late November [43]. After they were picked, they would be sun-dried and then boiled in water to form a mashed-up puree. This puree would be formed by using a hand cranked mixer until the soy beans resembled a thick soup/porridge. The soymilk would then be extracted by placing heavy objects and rollers on top of the puree mixture. Nigari, a precipitate made from sea water, would then be added to the soy milk[36].

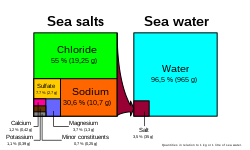

As mentioned above, Nigari is made from seawater, and thus may contain many salts (see diagram to the right).

After evaporation of the water, the major constituents that remain are Sodium, Chlorine, Calcium, Potassium, Magnesium and Sulphate.

Nigari serves as the coagulating agent and its content is largely Magnesium Chloride. However, because it is obtained from evaporated seawater, there are trace amounts of other salts as well, including Potassium Chloride and Calcium Chloride [33]. This not only allows for differences in the degree of moisture inside the tofu, but it also allows for elevated calcium levels. As such, adding seawater also serves as an appropriate coagulant and sometimes, may be the coagulant of choice, due to its added nutritional value [45]. The downside of using seawater is that it is more difficult to regulate the levels of salt to achieve the desired consistency and texture of tofu, since seawater content may vary and fluctuate. [33].

After the coagulating agent is added, the puree mixture is kept in a warm area that favors the production of lactic acid [43], which assists in the curdling process [46] of the soymilk. The warm temperature also helps to break down the soybean fiber and aids in the inactivation of an enzyme that hinders digestion. As such, tofu is very easily digested by most individuals [2]. The addition of coagulants and the warm temperatures modify the pH of the puree and assist in the curdling process, which is very similar to the curdling process in making cottage cheese [36].

To attain a more delicate texture, the curds are placed in wooden boxes, and a manual-lever press or a hand-turned screw press is used to pass the curds through a fine mesh strain. Afterwards, the curds are pressed again to form a more cohesive block-like structure. They are then either placed in water to retain moisture, or be cut to be stored or eaten. [43][36].

The following video is a demonstration of how tofu can be made traditionally. The tofu in the video was made by the steps underneath by one of our group members who is familiar with the traditional method of tofu production.

1) Wash the soy beans, and soak it in water for 8 to 18 hours. (This step will take longer in the winter time)

2) Mill and grind the soaked beans into a paste.

3) Simmer the paste over heat for approximately 15 min until the smell of the paste starts to deviate away from soy beans, and towards that of tofu.

4) Drain soy milk from the paste using cheesecloth, or other methods of separation.

5) Add Nigari to the soy milk and mix it in thoroughly.

6) After 10 to 30 minutes (depending on the quantity of soy milk and the consistency of tofu desired), pour the curd-containing suspension into a mold. Apply pressure on to the tofu by using weights.

7) Only remove the weights and the mold after a minimum of 15 minutes. The duration over which the pressure is applied will depend on the tofu consistency that is desired (For firmer tofu, leave the weights on for longer, and vice versa).

Commercial Method of Tofu Production

Although it is very similar to the traditional method, the modern process of making tofu is much more precise, and allows for tofu to be produced much more quickly. The process begins with soaking approximately 60 pounds of soy beans for 12-24 hours (the weight and times will vary based on the specific producer). The soy beans are considered ripe when the interior of the beans are one uniform colour [47]. The soy beans are then soaked in water until they double in size, after which they are heated and grinded [8]. To speed up the cooking process, all these steps are often performed in a pressure cooker. The soy milk is then physically separated from the pulp by a centrifuge machine [48]. All these steps are usually performed in the same machine. The use of the modern machinery allows for a more controlled cooking process, as well as a better yield when separating soy milk from the pulp. It also allows for better control of microorganism growth that can cause food borne illnesses, since the environment it is being produced in can be constantly monitored and cleaned. The commercialization of tofu manufacturing allows for much larger batches of soy beans, sometimes around 20 gallons of soy beans, to be cooked and processed at once [36]. The pulp that is extracted can be subsequently used to feed livestock [49].

Once separated, the soy milk can be transferred to the coagulation tanks where a coagulant, along with water, can be added (The water is added to activate the coagulant. However, not all coagulants require water) [36]. In commercial production, different coagulants can be added, such as Calcium Chloride and Magnesium Chloride. Although the composition of these coagulants is similar to that of nigari, the manufactured version of these coagulants is used because it allows for greater control [49]. These coagulants can be made by chemical reactions, such as the following to make Calcium Chloride and Magnesium Chloride:

From reaction (1), the gaseous CO2 can be released by agitating/stirring the vessel in which the reaction takes place. The formed Calcium Chloride (CaCl2) is dissolved in water due to a high solubility constant [50].

Therefore, the water can be added to the soy milk solution to allow for curdling. When ready, the curds, still hot and steaming, are poured through a perforated screen to drain off excess liquids. The heat allows for the maximum amount of the coagulant to remain dissolved, such that it will not affect the resultant tofu product [49]. The remaining curds are then transferred to large rectangular molds, and usually pressed with hydraulic or pneumatic presses. These presses are much more efficient than traditional lever or hand-crank presses, as they are much quicker to operate, and can deliver upwards of 130 lbs/in. of pressure to drain off all excess water (The amount of force applied will vary depending on what type of tofu is desired though) [36][8]. This molds the lumpy tofu into firm, rectangular blocks that are ready to be cut and packaged (See Left).

The tofu is packaged into a shrink wrap and vacuum sealed. It is then placed into thermoform packages (plastic molded to fit a particular shape, usually blocks), or placed into containers filled with water and any accompanying spices [36][51][52]. The sealed tofu is then weighed and dated. The final step in the tofu production is pasteurizing, which involves heating the food to at least 72oC for at least 15 seconds. This is also called a “High Temperature Short Time” (HTST) process [53]. Pasteurizing tofu not only inactivates pathogenic bacteria and viruses [53] but also extends the shelf life of the tofu to approximately 30 days, under refrigeration of below 7oC [36].

The following video depicts how tofu is produced in a commercial factory [8].

Differences between Commercial and Traditional Manufacturing Methods

The following table sums of some of the differences between the commercial and traditional methods of manufacturing tofu:

| Commercial Method | Traditional Method | |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Process | Largely automated with complex machinery able to process large amounts of soybeans. | Usually operated by hand/under human power and cannot handle as large a quantity of soybeans. |

| Machinery | Cooking is very precisely monitored to ensure cooking and inactivation of microorganisms. The machines are also used to speed up the cooking process (Eg. Pressure Cookers), and often perform multiple purposes (Eg. Cooking, mashing and separating soybeans from soymilk, all in one vessel. | Cooking is not as precise and often does not include procedures to inactivate microorganisms. Machines also usually do not have multipurpose capabilities. |

| Ingredients | Water, Soybeans and Coagulant. The coagulant is usually commercially produced by chemical reactions [50] and more than one type of coagulant may be used. | Water, Soybeans and Coagulant. However, the coagulant is made by adding direct seawater, or by evaporating seawater to create nigari. Therefore, the coagulants are taken from natural sources and are not human-made. |

| Safety from foodborne illnesses | Once packaged, tofu is pasteurized at temperatures above 80oC. This not only eliminates microorganisms, but also extends shelf life by approximately 30 days. During shipment and processing of packages, they must be refrigerated to below 7oC to maintain freshness.[36]. | May not undergo pasteurization, although different forms of preservation may be employed. Methods are usually also not as precise as commercial methods [43] |

In terms of nutrition, it is difficult to quantify whether one method of tofu production produces more nutrients than the other because it involves many factors (Eg. As seen above, even using different coagulants can lead to different nutritional values). The processing of tofu also adds to the variation of nutrients in commercially produced tofu. Different processing methods can lead to varying yields of soymilk and different concentrations/ratios of soy proteins. These could include differences in the water-to-bean ratio in soaking, the percentage of soybeans hydrated, the grinding and separation method, and the pores on the sieving and filtering apparatus [54]. The time of ripening of the soy bean could also account for nutritional differences, since they may contain proteins that are more or less easily extracted. As one can see, the resident proteins of tofu can be greatly influenced by the external stimuli that it encounters. Therefore, the relationship between the yield and nutritional quality of these proteins in the final tofu product is dependent on the processing method [54].

Review Question

Question

In commercial tofu production, which step in processing would you say has the greatest influence on the final nutritional outcome? Justify your answer.

Answer

The step that most likely influences the final nutritional outcome is the grinding and separation step. This is because the degree and duration of grinding can produce varying levels of proteins that may be extracted from separation. For example, a sample of tofu that has been ground for a longer time most likely has smaller protein subunits. Therefore, they will most likely be more soluble and be easier to elude in the soy milk extraction. (In this case, the major nutritional differences are in protein levels and therefore, the explanation focuses on this. Other answers may involve differences in fat content and carbohydrates. However, answers involving differences in cholesterol levels are not valid, since all tofu is virtually cholesterol free.[2])

Reflections and Conclusions

The methods of tofu production through traditional and commercial methods are similar in the sense that the ingredients and procedures are roughly similar. However, the commercial method makes use of coagulants other than the traditional nigari to obtain better curdling, as well as for economical purposes[9]. In commercial methods, the production of tofu is on a much larger scale, and the control of microorganism growth is also generally better regulated[36]. However, the nutritional value of tofu can vary greatly depending on the processing methods that are involved in the production of the tofu. Therefore, there are several factors to consider when debating between traditionally made or commercially made tofu (One must not forget the influences of cultural factors as well. For example, those who live in Japan may prefer tofu made through traditional methods). As a group, we feel that there is no definite "better" method in tofu production. Instead, we feel that the most important step is the learning and understanding of the science behind tofu production. This will allow consumers to make the best decision for themselves, their friends and families.

This project has shown us many new aspects of tofu production that we have never thought about. We often take the food we eat for granted, let alone gain an understanding of the processing behind it. By looking at tofu production from its traditional roots, and comparing it to the commercial mass-produced methods of today, we have gained a deeper appreciation for the science behind what seemed to be such a simple food. The health benefits, health risks and nutritional values associated with different types of tofu and different production methods are ones that are important to consider, and will ultimately influence our own personal decisions as consumers.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shurtleff, William and Aoyagi, Akiko. A Comprehensive History of Soy. Volume IV, Chapter 36: History of Tofu. California: Lafayette, 2007. SoyInfo Center. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 “What is Tofu?” Soya – Information about Soy and Soya Products. n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2013. <http://www.soya.be/what-is-tofu.php>.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Knopper, Melissa. “The Joy of Soy”. Rotarian 180.1 Jan 2002: 16. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wood, Rebecca. The Whole Foods Encyclopedia. New York: Prentice-Hall P, 1988. Print.

- ↑ Ko Minaya Wholefoods. “What is Tofu?” Ko Minaya Wholefoods, New Zealand. Web. 15 Feb 2013.

- ↑ “History of Tofu?” Soya – Information about Soy and Soya Products. n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2013. <http://www.soya.be/history-of-tofu.php>.

- ↑ Golbitz, Peter. “Traditional Soyfoods: Processing and Products.” The Journal of Nutrition (1995): 570S – 572S. Print.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 “How It’s Made Tofu” 20 Apr. 2012. YouTube. Web. 09 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Shurtleff, William and Aoyagi, Akiko. Tofu and Soymilk Production: a Craft and Technical Manual (3rd ed). California: Lafayette, 2000. Soyfoods Center. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Morinu. Silken Tofu. 08 Jun. 2012. Morinaga Blog. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Morinu. Firm Tofu. 08 Jun. 2012. Morinaga Blog. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hackett, Jolinda. “What’s the difference between Silken and Regular Tofu?.” About.com Vegetarian Food. n.d. Web. 22 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Nguyen, Andrea. “All about Silken Tofu.” The Kitchn. n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2013

- ↑ Fermented Tofu. Flickr. Yahoo! Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Godwin, Christopher. “Benefits of Fermented Soy.” Livestrong. 10 Oc. 2010. Web. 22 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Egg Flavored Tofu. Blogspot. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Hackett, Jolinda. “Tofu.” About.com Vegetarian Food. n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Ashton, E.L., Dalais, F.S., and Ball. M.J. “Effect of Meat Replacement by Tofu on CHD Risk Factors Including Copper Induced LDL Oxidation.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition 19.6 (2000): 761 – 767. Print.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ashton, E. and Ball, M. “Effects of soy as tofu vs meat on lipoprotein concentrations.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 54 (2000): 14 – 19. Print.

- ↑ Otvos, J. “Measurement of Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy.” Clinical Cardiology 22.2 (1999): II-21 – II-27. Print.

- ↑ Wu, A.H., Ziegler, R.G., and Horn-Ross, P.L. “Tofu and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 5 (1996): 901 – 906. Print.

- ↑ Canada. Health Canada. Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. [Ottawa]: Health Canada, 2011. Print.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hackett, Jolinda. “Tofu Nutritional Value Information.” About.com Vegetarian Food. n.d. Web. 05 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Firm Silken Tofu. n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/firm-silken-tofu>.

- ↑ Bruen, Judy. “List of Cholesterol in Different Cheeses.” Livestrong. 10 Mar. 2011. Web. 11 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Kritz-Silverstein, D and Goodman-Gruen, D.L. “Usual dietary isoflavone intake, bone mineral density, and bone metabolism in postmenopausal women.” Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine 11.1 (2002): 69 – 78. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Clarkson, Thomas. “Soy, Soy Phytoestrogens and Cardiovascular Disease.” The Journal of Nutrition 132.3 (2002): 566S – 569S. Web. 23 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Yamori, Y., Moriguchi, E.H., Teramoto, T., Miura, A., Fukui, Y., Honda, K., Fukui, M., Nara, Y., Taira, K., and Moriguchi, Y. “Soybean isoflavones reduce postmenopausal bone resorption in female Japanese immigrants in Brazil: a ten-week study.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition 21.6 (2002): 560-3. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Ensminger, Audrey H. Food for Health: A Nutrition Encyclopedia. Clovis: Pegus P, 1986. Print.

- ↑ Maldonado, I., Prasad, V. and Reginato, A.J. “Oxalate Crystal deposition disease. ” Current Rheumatology Reports 4.3 (2002): 257 – 64. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ United States. Center for Disease Control. Brief Report: Foodborne Botulism from Home-Prepared Fermented Tofu. California. 09 Feb. 2007. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Chan, Judy. “Food Standards, Regulations and Guides.” FNH. 200. Exploring our Food. U of British Columbia Vancouver. 11 Mar. 2013. Class Notes.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Liu, Keshun. Soybeans: Chemistry, Technology, and Utilization. New York City: Springer, 1997. Print.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Berk, Zeki. “Technology of production of edible flours and protein products from soybeans.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1992. FAO Corporate Document Repository. Web. 14 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Lu, J.Y., Carter, E., and Chung, R.A. “Use of Calcium Salts for Soybean Curd.” Journal of Food Science 45 (1980): 32 – 34. Print.

- ↑ 36.00 36.01 36.02 36.03 36.04 36.05 36.06 36.07 36.08 36.09 36.10 36.11 Avizienis, A. “Tofu.” How Products Are Made. n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Extra Firm Tofu (Prepared with Nigari). n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/extra-firm-tofu-(prepared-with-nigari)?portionid=61087&portionamount=100.000>.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Hard Tofu (Prepared with Nigari). n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/hard-tofu-(prepared-with-nigari)?portionid=61088&portionamount=100.000>.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Firm Tofu (With Calcium Sulphate). n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/firm-tofu-(with-calcium-sulfate)?portionid=61148&portionamount=100.000>.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Regular Tofu (With Calcium Sulphate) . n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/regular-tofu-(with-calcium-sulfate)?portionid=61149&portionamount=100.000>.

- ↑ FatSecret All thing Food and Diet. Food Database and calorie counter, Firm Tofu (Nigari with Calcium Sulphate and Magnesium Chloride). n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2013. < http://www.fatsecret.com/calories-nutrition/usda/firm-tofu-(nigari)-(with-calcium-sulfate-and-magnesium-chloride)?portionid=61066&portionamount=100.000>.

- ↑ Canada. Health Canada. Food Additives Permitted for use in Canada. Canada, 11 Dec. 2006. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Shurtleff, William and Aoyagi, Akiko. A Comprehensive History of Soy. Volume IV, Chapter 35: History of Soymilk and Dairy-like Soymilk Products. California: Lafayette, 2007. SoyInfo Center. Web. 13 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Hashimoto, Toshio. Nigari composition. 25 Jun. 1997. Salt Industry Center Foundation, Engineering Department. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Van der Riet, W.B., Wight, A.W., Cilliers, J.J.L., and Datel, J.M. “Food Chemical Investigation of Tofu and its Byproduct Okara.” Food Chemistry 34 (1989): 193 – 202. Print.

- ↑ Chan, Judy. “Food Preservation with Biotechnology.” FNH. 200. Exploring our Food. U of British Columbia Vancouver. 11 Mar. 2013. Class Notes.

- ↑ “How is Tofu Made?” 20 Apr. 2012. YouTube. Web. 07 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ What is Tofu? How is Tofu made? Tofu Textures & Uses from Nasoya. n.d. Web. 19 Mar. 2013. < http://www.nasoya.com/how-to/what-is-tofu.html>.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Wang, H.L., Swain, E.W., and Kwolek, W.F. “Effect of Soybean Varieties on the Yield and Quality of Tofu.” Cereal Chemistry 60.3 (1983): 245 – 248. Print.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Hebden, James. Chemistry 12, A Workbook for Students. Kamloops: Hebden Home Publishing, 1998. Print.

- ↑ Throne, James. Technology of Thermoforming. Cincinnati: Hanser/Gardner Publications. Inc., 1937. Print.

- ↑ Tofu. n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2013. <http://www.soyfoods.com/soyfoodsdescriptions/tofu.html>

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Chan, Judy. “Thermal Preservation of Foods.” FNH. 200. Exploring our Food. U of British Columbia Vancouver. 20 Mar. 2013. Class Notes

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Cai, T and Chang, K.C. “Processing Effect on Soybean Storage Proteins and their Relationship with Tofu Quality.” Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry 47.2 (1999): 720 – 727. Web. 24 Mar. 2013