Course:FNH200/2011w Team05 Mycoprotein

Introduction

Mycoprotein is a meat substitute produced by Fusarium venenatum. [1]It is textured and flavoured to resemble meat. It is suitable for vegetarians, but not vegans because egg albumin is used as a binder in the product.[1] It is also used as a food ingredient in QuornTM.

Mycoprotein is produced by biotechnology under a continuous fermentation process of fungus Fusarium venenatum, on a carbohydrate substrate.[1] It is a high protein, high fibre and low fat food which has a relatively low caloric, saturated fat, salt and sugar content than red meat.[1]

Various studies indicate that mycoprotein is health beneficial. It plays a role in cholesterol reduction, satiety, and management of glycaemia and insulinaemia.[1]

It was developed during the 1960s and 1970s, when nutritionists and politicians were concerned about the food and protein shortages due to the rapid population growth.[1]

Mycoprotein is sold as a trademark “Quorn” in the retail market. It was produced by Marlow foods, North Yorkshire, UK. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in UK approved its sale in the retail markets in 1985.[1]It is widely available across Europe, United States in 2002 and Australia in 2010. [2]It is manufactured as pies and pastry, mince, chicken nuggets, fish fillets and ready meal.

However, its safety is a huge concern over the years. According to some studies in Europe, there is about 1 in 100,000 to 200,000 people that may react to the mycoprotein simply because it is made of fungi.[2]They suffer from allergic reactions including diarrhea, violent vomiting and stomach cramps. [3]800 people from United Kingdom and United States have reported to suffer from gastrointestinal problems after consuming QuornTM. [3]

Characteristics

Mycoprotein is made up of filaments, hyphae. It is similar to the structure of animal muscle cells, for example high length to diameter ratio.[4]These filaments are responsible to the meat like texture. This also creates a compact and dense internal structure for QuornTM.

Mycoprotein has a relatively lower caloric content than meat. It is a high protein and fibre food. It has lower saturated fat and sodium content, compared to other protein sources. It does not contain cholesterol and trans fat. In addition, it contains all of the essential amino acids.[5] Its concentration of essential amino acid is similar to that of egg.[4]

High content of dietary fibre in microprotein is thought to play a role in lowering LDL blood cholesterol concentration.[5] It serves the purpose of reducing energy consumption because it increases the satiety. The fibre content and amino acid composition in fibre are thought to be able to control blood sugar level.[5] It assists in managing obesity and type 2 diabetes. Thus, mycoprotein promotes benficial health effects on human body.

Where Mycoprotein Is Used

Mycoprotein can be found in a variety of products which allow the consumer to taste a meat-like texture.[4] Some of these products include:

- Escalopes - Ready-made meals - Deli slices - Sausages - Chicken-style products, such as: nuggets, patties, tenders, cutlets - Lasagna

Functions

In the 1960s, due to the rapidly increasing world population, it was predicted that, by the 1980s, there would be a shortage of protein-rich foods. In response, there was research done to find new plant and vegetable-based foods to satisfy this predicted shortage. A search for a suitable organism followed, taking soil samples from around the world, eventually testing 3000 organisms[4]. After considering the alternatives, it was decided that Fusarium venenatum was the best option - an organism naturally occurring in the soil in a field in Marlow, Buckinghamshire - and after a ten-year screening process, mycoprotein was for sale for human consumption for the first time in 1985 [6]. The original function of mycoprotein was therefore to combat a predicted food shortage, acting as a food supplement. It was developed as a source of protein, out of apparent necessity more than anything else.

When the predicted food shortage failed to occur, the original intended function of mycoprotein - to act as a necessary food supplement - was no longer necessary. The increasing popularity of vegetarianism, however created another possible role for mycoprotein. The main function then, and now, for mycoprotein was again to act as a food-supplement, but in this case to act as a meat alternative.

Mycoprotein is advertised as a healthy, meat-free source of protein [6]. As was mentioned above, additional characteristics of mycoprotein that make it an attractive meat-substitute are its low fat content, lack of cholesterol or trans fat and its high dietary fibre content. In addition to its health benefits, Quorn claims that it requires five times less energy to produce one gram of Quorn than it does one gram of meat. Furthermore, the company says that factory-produced Quorn is even more ecologically friendly than growing large fields of soybeans for soy-based meat substitutes.[7]

The most appealing sensory function of mycoprotein, however is its texture. When developing new foods, desirable taste and colour are relatively easy to achieve. Achieving an appealing texture for meat-substitutes, however, has proved to be the more difficult. The microfungus from which mycoprotein is produced, Fusarium venenatum, is comprised of a web of finely spun strands. These strands have a similar structure to animal muscle cells and therefore contribute a texture similar to that of meat. This firmness is an important function in the meat-substitute food products produced using mycoprotein.[8]

Mycoprotein is also effective at absorbing flavors and colours. Products using mycoprotein can therefore substitute for a variety of different meats. Without any flavour of its own, mycoprotein can totally absorb flavour without any competing flavours already existing in the product, leading to a more distinct and flavorful product compared to some other meat substitutes [8] .

How Mycoprotein Is Manufactured

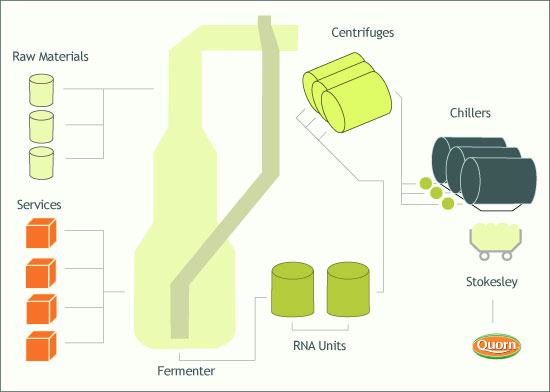

Mycoprotein is made in 40 metre high fermenters. Each of these continuously run for five to six weeks at a time. The fermenter then goes through a sterilization process of two weeks.[9]. It is then filled with a water and glucose solution. Next, a batch of Fusarium venenatum, the fungi that is the base for Mycoprotein, is introduced.

Once the organism starts to grow, a continuous feed of nutrients such as potassium, magnesium and phosphate and trace elements are added to the solution. The pH balance, temperature, nutrient concentration and oxygen are all constantly adjusted to reach the optimum growth rate.

The organism and nutrients come together to form Mycoprotein solids, and these are removed continuously from the fermenter after an average ‘residence time’ of five to six hours. After it is removed, the Mycoprotein is heated to 65°C, a treatment which provokes the breakdown of most of the fungal nucleic acid, the level of which would otherwise exceed health and safety limits.[9] . Water is then removed in centrifuges, and the Mycoprotein left resembles a pasty dough and has a mushroom-like smell.

Next, the Mycoprotein is mixed with a little free range egg and seasoning, to help bind the mix. It is then steam cooked for about 30 minutes and then chilled, before it is minced or chopped into pieces.

The product is then frozen. This is a very important part of the process, due the fact that the ice crystals help to push the fibres together, creating bundles that give Mycoprotein its meat-like texture. The pieces and mince are then sold under the Quorn™ brand and in a wide range of other products.

Regulations

There are no regulations in Canada that explicitly disallow the sale of mycoprotein products. However, there are regulatory barriers that apply to simulated poultry products, in which mycoprotein falls under. According to section B.22.029. on Canadian food and drug regulations, there are various requirements for minimum key nutrients which much be met before a simulated poultry products can be sold.[10] The products of Quorn, the leading brand for mock meat mycoprotein products, do not fulfill these requirements[6] and as fortification of their products with nutrients does not meet with their brand values, Quorn products can not be found in Canada.[11]

In the United States, mycoprotein has the status of "Generally recognized as safe"(GRAS) and is exempt from food additive tolerance requirements.[12] Where as in Australia and the United Kingdom, mycoprotein products are not identified as a Novel Food due to its history of consumption without major health concerns, which means that no assessment of its public health and safety is necessary.[13]

Popularity

As global population continue to increase and with more and more people striding to maintain good health, there is a need to find protein food sources other than from meats [14]. Mycoprotein, which its trademark name is Quorn, is one of the many alternative protein sources that have been discover over the past century [14]. First being discovered in 1967, in Marlow, Buckinghamshire in the United Kingdom it was first approved for consumption in 1985 in the UK [1]. Since then, the company has grown, and mycoprotein products are available in many countries. Most of these countries are within Europe, which includes the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Demark, and Norway [6]. Two countries outside of Europe have also approved the sale of Quorn products; first is the United States which started to sell Quorn in 2002 and recently in 2010, Quorn was introduced into the Australian market [6]. Canada has not approved this product.

The Quorn has also increased in the range of products it has to offer over the years. The first Quorn product was a vegetable pie that contained mycoproteins [6]. Nowadays, mycoprotein is used to meat substitution products that range of fillets to cold-cut styled slices to sausages to wings to pastries[1]. In 2004, the McDonalds in the UK introduced their new vegetarian burger which was made from mycoproteins [15]. Although today’s UK McDonald menu no longer features any vegetarian burger, this product’s popularity has been steadying increasing [16].

It is reported that 23 million Europeans had consumed a Quorn product in 2001 and that 500 000 Quorn products are consumed each day in the United Kingdom [1]. By 2006, Marlow foods the company that produces the Quorn food product line, claims that one in five household in the UK have consumed some kind of Quorn product [6]. The sales numbers shows how popular such a product is; in the Natural and Organic Foods and Beverage Treads in the U.S. report published by Package Facts, they found Quorn’s sales had increase 286.4% from 2003 to 2007 [17].

Controversy

Deceptive Labeling

In 2002, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which is a non-profit advocacy group focused to inform consumers about health, nutrition and environmental issues that affects the consumers, filed a complaint about Quorn mislabelling their products [18]. Quorn had labeled their products to be from a mushroom origin, while in truth, mycoproteins are from a fugal that has no linkage to mushrooms [18]. The group also claimed that some of the Quorn products did not even list where mycoprotein comes from [18]. Another complaint the Center for Science in the Public Interest had made was that Quorn had also publish false claims. The Center for Science in the Public Interest had found products that claim mycoprotein is made from a vegetable protein and is a “plant occurring naturally in soil”, again this is not true [18]. Mycoprotein cannot be made from a vegetable protein as it comes from a fungal protein and it is false to call it a plant that is naturally found in soil. Although this fungus is found in soil, the Center for Science in the Public Interest believes in it necessary that the Quorn products specify that mycoprotein is made in large fermentation barrels [18]. The advocacy group feels these deceptive labels causes consumers to make skewed decisions towards the consumption of mycoprotein [18].

Allergen

The Center for Science in the Public Interest group has also complained about mycoprotein being an allergen and should have more adequate tests done on it before it is deemed good for consumptions[18]. They have a self reporting service for people to report any allergic reactions they have towards Quorn products [19]. The company had received 284 self-reported of allergic reactions towards Quorn products in 2003 [19]. Of the complaints, 80% of them were by UK residents[19]. The symptoms that were reported included: vomiting, diarrhea, rashes, hives and asthma attacks[19] . Reaction toward the mycoprotein differs from person to person, with some reported that symptoms began minutes after consumption to hours after consumption [19]. The Canadian Broadcast Corporation has reported that 1 in 146 000 have an allergic reaction towards mycoproteins [20].

In one case, a 41 year old man had a severe reaction after consuming Quorn. This happened in 2003, and this middle aged man had a history of asthma [21]. After he had consumed the Quorn product he began to have blister on his skin and asthma attacks [21]. At first no one knew what had caused those symptoms, but after completing several scientific tests, it was proven that he was allergic to the mycoprotein in the Quorn product [21]. The Food Standard Agency did not find this case surprising as allergens are usually proteins and Quorn is a high protein food [21].

Mycoprotein vs. Soy-based Protein

Soy-based products are the most common substitute for meat due to its high-protein content. There are both advantages and disadvantages to using and consuming mycoprotein over soy-based proteins such as tofu. There have been multiple studies conducted to determine the health benefits of all meat-substitutes but many aspects of the long-term health effects have yet to be agreed upon by scientists and researchers.

The first advantage to mycoprotein is its high-fibre content. It has been found to have satiating properties which can reduce the feelings of hunger for a long period of time after consumption. Soy protein has also proved to have satiating properties however, the effects are shorter-term then the effects of mycoprotein. [22]

Another comparison which exists is in cholesterol levels. For this health benefit soy protein and mycoprotein have shown similar effects. Soy protein has been found to lower bad cholesterol and raise good cholesterol. The FDA even approved a health claim in the United States for cholesterol reduction from soy protein. The exact mechanism in the soy which does this is still unclear but it is thought that the isoflavons may play a role. Similarly, the high-fibre content of mycoprotein has also proved to reduce bad cholesterol levels. [1]

Health is not the only consideration when it comes to comparing mycoprotein and soy protein. Flavour and texture are also significant factors in meat substitutes. The taste of the protein and how it feels compared to real meat plays a large role in whether people will purchase the product or not. A meat-like texture can be more effectively reproduced with mycoprotein compared to soy-based protein. This is because mycoprotein is made out of mushrooms which consist of fibrous carbohydrates. The fibrous nature more closely models the fibrous texture of meat. With regards to flavour, soy protein tends to be very bland therefore, flavour enhancers such as acid-hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP) and monosodium glutamate (MSG)are often added. Mycoprotein naturally has a stronger flavour than soy protein and so flavour enhancers do not need to be added in order to make the flavour more closer resemble that of meat. [7]

A Quorn-y Video

Check out this video which talks about the origin of mycoproteins (from 1:15 - 2:10). This video also talks about other meat alternatives.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Denny, A., Aisbitt B., & Lunn, J. (2008). Mycoprotein and health. Nutrition Bulletin, 33, 298-310. doi:10.1111/j.1467-3010.2008.00730.x. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2008.00730.x/full

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (2011). Quorn (mycoprotein) Retrieved from http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/factsheets/factsheets/quornmycoproteindece5078.cfm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Warner, M. (2005, May 3). Lawsuit Challenges a Meat Substitute. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/03/business/03food.html?_r=2&ex=1272772800&en=e24a69012b5704e6&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Marlow Foods Ltd. What is Mycoprotein?. Retrieved from http://www.mycoprotein.org/what_is_mycoprotein/index.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wiebe, M. G. (2002) Myco-protein from Fusarium venenatum: a well-established product for human consumption. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 58, 421-427. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-0931-x Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/abf1xf6g00jrwjpb/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Quorn. Marlow Foods Ltd, 2011.18 Mar. 2012.Retrieved from http://www.quorn.com

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Manjoo, F. (2002, April 16). A Mushrooming Quorn Controversy. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2002/04/51842

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Morel, J. (2011, May 26) What Are The Benefits Of Mycoprotein?. Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.com/article/449791-what-are-the-benefits-of-mycoprotein/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Retrieved from http://www.thedesignline.co.uk/ibo/documents/Mycoprotein.doc/ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "manufacturing" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Department of Justice Canada, Food and Drug Regulations. (2012). Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._870/page-169.html

- ↑ British Expats. (2010). Retrieved from http://britishexpats.com/forum/showthread.php?t=680672

- ↑ US Food and Drug Administration. (2001). Retrieved from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fcn/gras_notices/grn000091.pdf

- ↑ Food Legal Bulletin. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.foodlegal.com.au/bulletin/articles/is_fsanzs_approach_to_quorntm_mycoprotein_consistent_with_previous_fsanz_policy/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ward, Valerie. "Muscling Up." Food in Canada 71.7 (2011): 62,62,64,67. CBCA Complete. 18 Mar. 2012.

- ↑ Wentz, Laurel. "The World." Advertising Age 76.35 (2005): 13-. ABI/INFORM Global. 18 Mar. 2012.

- ↑ McDonald, 2012. Web. 17 Mar. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.mcdonalds.co.uk/ukhome/Food.html

- ↑ Levine M. “Natural and Organic Food and Beverage Trends in the U.S.: Current and Future Patterns in Production, Marketing, Retailing, and Consumer Usage.” Packaged Facts 2008: 66-67. Print.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 “Quorn” Meat Substitutes Deceptively Labeled, Says U.S. Consumer Group. CSPI Quorn Complaints. Retrieved from http://www.cspinet.org/quorn/quornpr_032102.html

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Jacobson, M. F. (2003). Adverse reactions linked to Quorn-brand foods. Allergy, 58 (5), p455-456, 2p.

- ↑ CBC News. (2002, Apr. 3) Science organization wants tests on new meat substitute. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/story/2002/04/02/Quornmeat_020402.html

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 BBC News. (2003, May 30). Quorn linked to asthma attack. BBC News. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/2949510.stm

- ↑ Williamson, D. A., Geiselman, P. J., Lovejoy, J., Greenway, F., Volaufova, J., Martin, C. K. A., Arnett, C., & Ortego, L. (2006). Effects of consuming mycoprotein, tofu or chicken upon subsequent eating behaviour, hunger and safety. Appetite, 46(14), 1-48. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666305001455