Course:FNH200/2011w Team02 MSG

Introduction

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a flavor enhancing molecule used as a food additive and is closely associated with the fifth basic taste, "umami". Much discussion and debate has surrounded the health effects and safety issues of MSG usage in foods. Furthermore, relatively little is known about the mechanism behind the flavor enhancing properties of MSG. However, in the case of food additives, often public concern is misdirected due to a lack of understanding or awareness. In order to formulate an informed opinion about the safety and usage of MSG, an examination of the related background, current research and regulating laws is required

History

Invention

In 1908, a chemistry professor at the Imperial University of Tokyo, Kikunae Ikeda, observed that the dominant taste of konbu dashi, a Japanese soup base is clearly different the four basic tastes—sweet, bitter, salty and sour.[1] He isolated the substance contributing to this special taste from seaweed Laminaria japonica by aqueous extraction, crystallization of contaminants, lead precipitation and low-pressure evaporation successively. He called this taste umami which derived from the colloquial masculine word in Japanese meaning delicious.[2]

Coming to Market

Suzuki Chemical Company created a brand Ajinomoto meaning "essence of taste" in 1909 and since then, MSG came to market officially. The product, monosodium glutamate was rapidly patented in Japan, the United States, England and France.[2]

Crisis and Response

Consumer trust in the food industry broke down famously in the 1960s. On October 23, 1969, Jean Mayer chair of the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health, recommended MSG be banned in baby foods. Dr. John Olney stated injections of monosodium glutamate caused brain damage in the same year. [3] Despite testimony from Olney, further animal studies, and anecdotal evidence reported by numerous doctors through the 1970s, MSG was never banned or subjected to further regulation.

Reinvention

Since 2000, American physiologists have announced several finding indication a group of molecules on the tongue that respond specifically to the stimulus MSG induces. The journal Nature reported in February 2002 that “researchers have pinpointed the receptor that allows us to taste proteins’ building blocks”. [1]Like saccharin and many other ambiguous substances in the contemporary world food system, MSG continues to be consumed even as the controversy bout its health effects persisted.

Usage

MSG is commonly used to increase the palatability of foods and is used to increase the intensity of other flavours.[4] It is used to enhance and bring out the umami sensation in foods that lack flavour. It is particularly common to see the use of MSG in Chinese Restaurants because it has been said to be a quick way to make the dish flavourful and savoury.[5] MSG is also produced by Ajinomoto for personal use and home cooking. It is used in small amounts because adding an excess does not increase the intensity of the flavour more than it already does.[6]

Because of its flavour enhancing capabilities, MSG is more commonly used in packaged foods. This is because foods that go through processing such as freezing, dehydration, and canning would also lose flavour.[5] Therefore, the addition of monosodium glutamate brings out the original flavour so that the product would be similar to initial state. MSG is commonly found in foods such as crackers, seasoning, salad dressings, ice cream, and other milk products that have undergone processing.[5] Foods such as natural flavourings, vegetable proteins, east extract, textured soy protein, vegetable/chicken/beef broth, and carageenan are all common ingredients found on packaged products that may not directly state that there are traces of MSG.[5]

The wastewater of MSG can also be used as a low-cost fertilizer because it controls the pH levels in the soil.[7]

Structure and Method of Production

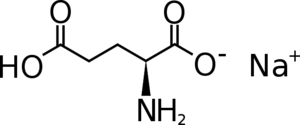

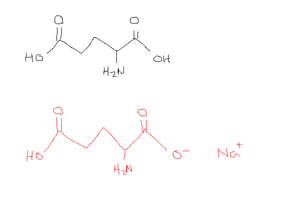

Monosodium glutamate has a molecular formula of C5H8NNaO4 and is the sodium salt of glutamic acid. [8] It has a chirality center at C2, and therefore has stereoisomers. However, only the L-isomer species has the flavour-enhancing properties ("umami").[8]

Since the introduction of MSG in 1890, there have been 3 major methods of manufacturing: protein hydrolysis, chemical synthesis, and bacterial fermentation. [8]

Protein Hydrolysis

Vegetable proteins, such as wheat gluten (contains high amounts of L-glutamine [9]) are heated in acidic solution. The peptide bonds become unstable in acid and will break, liberating individual amino acid molecules. Some of these are glutamic acid molecules, which can be isolated as crystals. Glutamic acid molecules are further treated with sodium hydroxide to yield monosodium glutamate salt.This was the earliest means of producing MSG (1909 - 1962), but due to the increase in demand, it has been replaced with more efficient methods. [8]

Chemical Synthesis

Around 1962, chemical synthesis of MSG using acrylonitrile (C3H3N) began in Japan. In this process, a gas mixture (hydrogen and carbon monoxide), ammonium cyanide, and sodium hydroxide are added to acrylonitrile in presence of acid to yield a racemic mixture of glutamic acid. The L-glutamic acid is specifically crystallized and centrifuged out of the solution. The crystals are then neutralized and processed of MSG. [9]

Bacterial Fermentation

Currently, the predominant manufacturing process of MSG is via bacterial fermentation (e.g. Micrococcus glutamicus).[8] Similar to wine production, microbes are used to convert carbohydrates into amino acids. First, bacteria is cultured with ammonia, hydrochloric acid, and carbohydrates (e.g. from sugar beets or tapioca). As a metabolic byproduct, they will secrete animo acids into the culture medium, from which glutamic acid can be isolated. After filtration, crystallization, and dehydration, pure MSG can be collected. [10]

Health Concerns and Allergies

Since MSG is not a protein, it can't be classified as a true allergen. However, it is possible for individuals to have "MSG sensitivity". In a sensitivity, there are no antibodies involved, instead, a bodily reaction still occurs. [11]

The most famous example of MSG symptom would be the "Chinese Food Syndrome" (CFS). This MSG symptom complex, which includes many of the common MSG side effects, also can cause headaches, palpitations, flushing, sweating, sour stomach, weakness, and numbness around the mouth and chest pain.[12]

MSG is free glutamic acid and can also be known as glutamate, which is the ionized form. It is a neurotransmitter and stimulates nerve cells. MSG stimulates the nerve cells in the human mouth as well as the brain, specifically the centers of hunger, taste, and smell. However, we cannot confirm that there is a relationship between MSG and allergy. Although it does not initiate the allergy, there is a chance that it affects the allergy response.

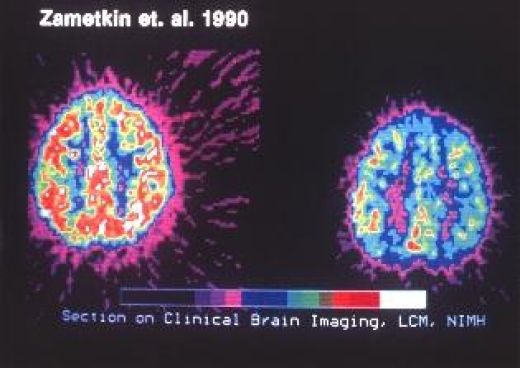

According to research from Johns Hopkins, the immune system can be disturbed by the over-stimulation of the nervous system. This is a problem because MSG is a nervous system excitatory neurotransmitter, also know as an excitotoxin. Excitotoxins are substances believed to damage the brain and central nervous system. Excitotoxins tend to affect the hypothalmus, which controls important bodily functions such as growth, sleep patterns, puberty and appetite. Some studies suggest that MSG inhibits the normal function of the hypothalmus, which can cause long-term negative effects such as obesity, sleep disturbances and reproductive issues. Rodents that were fed MSG became obese and pre-diabetic. [13]

Too much MSG introduced to the brain can cause rapid cell death. Glutamate over-stimulates areas of the brain, resulting in neuronal cell death. According to John Erb's theory, since the placental barrier of a pregnant woman is not complete at the first month of fetal development, glutamate can easily be passed to the fetus. If it stimulates rapid growth in the brain, there is a possibility that the fetus may have ADHD symptoms. If it cause neuronal cell death, it leads to autism. [14]

MSG can cause severe breathing difficulties especially in asthma patients. Breathing can become extremely labored in some cases and may require medical attention. A study by Johns Hopkins University suggests that monosodium glutamate may even induce asthma in some individuals. Other studies show that MSG can cause damage to brain cells and the central nervous system. Some studies suggest it has direct correlations with Alzheimer's disease.

Sensory Perception

MSG has a unique role in the taste perception of foods. It is a part of a classification of compounds called “flavour enhancers or potentiators”[15]. This classification also includes the nucleotides 5'-inosine monophosphate (IMP) and 5'-guanosine monophosphate (GMP) [16] IMP, GMP and the amino acid glutumate occur naturally in many foods such as meats, seafood, cheeses, human breast milk, and vegetables (especially mushrooms) [16].

Umami

The combination of glutamate and nucleotides elicit the umami taste sensation. Umami is considered a unique taste because it can not be produced by blending any of the four other basic tastes (sweet, salty, bitter and sour) [16] Umami is a Japanese word meaning “savoury” and is described as “meaty”, “broth-like” or imparting a sense of “mouthfulness” [17]. The group of flavour enhancer compounds are unique in that alone they elicit either no taste or a soapy metallic or bitter taste. [18]. However, when added to certain foods, they increase palatability and flavour. When MSG is added, meat and vegetable flavours are judged as more intense, but minimal sensory effects are observed in sweet, doughy and acidic foods [5] This may be a result of the synergistic effect of MSG with IMP and GMP. When the nucleotides are present in a food, a small amount of MSG increases the umami taste 8 fold [19].

Interestingly, MSG does not need to be present at identifiable levels in order to elicit its flavour enhancing effect. This effect is optimal when MSG is present at a concntration of 0.4%–0.6%, and is actually judged as unpleasant at higher ranges of 0.094%–6%. However, Japanese subjects seem to prefer greater concentrations of MSG, suggesting the possibility of cultural variability in sensory perception of the Umami taste. [18]

MSG appears to have an important role in the sensory perception of broths, and is often added to commercially produced soups. Although aroma is not affected by the addition of MSG, aspects of continuity, 'mouthfulness', impact, mildness and thickness are increased [16].

Mechanism of Perception

The perception of the taste of umami is the result of a very complex process. There are specific taste bud receptor sites for umami, which trigger a series of cellular and neural responses when stimulated. Studies indicate that although the neural response pattern for the umami taste is unique, it is related most closely to the sweet taste sensation, while also sharing several response characteristics with Sodium Chloride (table salt).[18]

Other Sensory Components

MSG has no effect on the aroma of food and there are no peer-reviewed sources that indicate any effect on food appearance. The additive does not influence perception of the sweetness, saltiness, sourness, or bitterness of foods. However, recent research has investigated the use of MSG to reduce the salt content of processed foods. Alone, MSG does not impart a salty taste, and therefore likely could not be used as a direct salt substitute. However, studies indicate that the addition of MSG to foods with reduced salt content protects against the perception of the foods as less palatable [16]. This is an exciting discovery given the health problems associated with over consumption of sodium in the Western diet and the current lack of a palatable salt substitute [15]. MSG also appears to have an effect on the eating process itself. MSG stimulates the hypothalamus and is correlated with more rapid ingestion of food (faster chewing as well as fewer and shorter pauses). Several studies have investigated the use of MSG in appetite stimulation for the elderly and other populations at risk of malnourishment. [18]

Labeling and Regulations

The health and safety standards of MSG in food as well as the development of food labelling policies is regulated by Health Canada under the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations while the specific administration of food labelling policies and enforcement of regulatory labelling requirements is done by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.[6] MSG is considered to be a flavor enhancer and not a food additive as some may think meaning it is exempt from the strict food additive regulations cited under Division 16 of the Food and Drugs Regulations. [20].

Since MSG is considered a flavor enhancer there is no limit to the amount of it that can be put in food products, but Health Canada says companies should follow Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) so use only the smallest amount necessary for taste. The labelling of MSG applies to prepackaged foods only so as to inform consumers who are ‘sensitive’ to the flavor enhancer. Statements such as “contains no MSG”, “no MSG added”, and “no added MSG” are not recommended since it can be misleading to the consumer as to the fact that MSG occurs naturally in many foods. The natural forms of glutamate that can be found are in hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP), hydrolyzed plant protein (HPP), hydrolyzed soy protein (HSP) soya sauce or autolysed yeast extracts which are common in processed foods. Naturally occurring glutamate can also be found in tomato juice, grapes, cheeses, and mushrooms and therefore it is not a required that the product needs a label to indicate the presence of glutamate. Health Canada sets forth some general guidelines for consumption stating 5 milliliters of MSG per kilogram of food and 2 milliliters of MSG per six servings of vegetables are a good starting point for consumption. [6]

Different countries have different stances on this compound with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) declaring it as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) while the European Union declares it as a strict food additive. On many labels, monosodium glutamate is also written as E621. Therefore it is important for consumers to be familiar with the common names of MSG so that they are knowledgeable about the product they are consuming wherever they are. [21]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jordan Sand (2005) A Short History of MSG: Good Science, Bad Science, and Taste Cultures.The Journal of Food and Culture, 5(4),38 <http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/openurl?issn=1529-3262&title=&volume=5&date=2005&issue=4&spage=38>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lindemann B, Ogiwara Y, Ninomiya Y (2002). "The Discovery of Umami". Chem Senses 27(9),843

- ↑ Ajinomoto kabushiki gaisha, Aji o tagayasu(2000) "An Eighty-Year history of Ajinomoto" Tokyo: Ajinomoto kabushiki gaisha 352-353

- ↑ Kemp, S. and Beauchamp, G. (2006). Flavour Modification by Sodium Chloride and Monosodium Glutamate. Journal of Food Science, 59(3), 682-686

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Scarpa, J. (1993). Monosodium glutamate. Restaurant Business, 92(5), 88.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)- Questions and Answers. (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2012 from Health Canada. Website:<http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/securit/addit/msg_qa-qr-eng.php>

- ↑ Singh, S., Rekha, P.D., Arun, A.B., Huang, Y.-M., Shen, F.-T., Young, C.-C. (2011). Wastewater from monosodium glutamate industry as a low cost fertilizer source for corn (Zea mays L.). Biomass and Bioenergy, 35(9), 4001-4007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 [1], Romanowski, Perry. "Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) - Characteristics of MSG." Science Encyclopedia. Net Industries. Web. <http://science.jrank.org/pages/4434/Monosodium-Glutamate-MSG.html>.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 [2], Sano, Chiaki. "The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition." History of Glutamate Production. American Society for Nutrition, 29 July 2009. Web. 19 Mar. 2012. <http://www.ajcn.org/content/90/3/728S.full>.

- ↑ [3], Wikipedia contributors. "Monosodium glutamate." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Web.<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monosodium_glutamate>.

- ↑ MSG and Allergy. (n.d.). Retrieved on March 22, 2012 from MSGTruth. Website: <http://msgtruth.org/allergy.htm>

- ↑ Monosodium Glutamate: Poison the Body to Better the Taste. (n.d.). Retrieved on March 22, 2012 from Worldwide Health Center. Website: <http://www.worldwidehealthcenter.net/articles-445.html>

- ↑ Health Risks of Monosodium Glutamate. (n.d.). Retrieved on March 22, 2012 from EHow Health. Website: <http://www.ehow.com/about_5432119_health-risks-monosodium-glutamate.html#ixzz1pXhicOuz>

- ↑ Autism and ADHD Linked to Addictive Food Additive. (n.d.). Retrieved on March 22, 2012 from La Leva. Website: <http://www.laleva.org/eng/2004/03/autism_and_adhd_linked_to_addictive_food_additive.html>

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Chan J. (2012). Fat and sugar substitutes – Sensory perception of foods. Food Nutrition and Health 200, University of Britsh Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Fuke, S. and Shimizu, T. (1993). Sensory and preference aspects of umami. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 4, 246-251

- ↑ Ninomiya, K. (2002). Umami: a universal taste. Food Reviews International, 18(1), 23.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Bellisle, F. (1999). Glutamate and the UMAMI taste: sensory, metabolic, nutritional and behavioural considerations. A review of the literature published in the last 10 years. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, 23(3), 423-238.

- ↑ Rouhi, M. (2003). Monosodium glutamate. Chemical and Engineering News, 81(30), 57.

- ↑ Food Additives. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2012 from Health Canada. Website:<http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/securit/addit/index-eng.php>

- ↑ Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2012 from Food Standards Agency. Website:<http://www.food.gov.uk/safereating/additivesbranch/enumberlist>