Course:FNEL 380/Using Audio in Language Documentation

In the past, linguists have assigned the highest priority to the traditional products of descriptive linguistics: namely, a grammar, a lexicon, and a corpus of interlinear texts.[1] More recently, however, there has been a shift towards language documentation, rather than description, and audio has been a primary tool for this process. Audio recordings are often the first line of action for preserving language events, and different methodologies regarding recording have surfaced. In particular, this page will discuss Basic Oral Language Documentation.

Three Basic Kinds of Oral Annotation

- Careful speech:

- Otherwise known as oral transcription

- Provides clearer interpretation of the phones involved in the diction

- Phrasal translation:

- Each phrase is translated into a language of wider communication

- Analytic comments:

- Contextual information for mother-tongue speech events

- Information that is original to mother-tongue speakers, but is then made accessible to non-native speakers via a language of wider communication

- i.e. Implied information, cultural knowledge, folk classifications[2]

- Contextual information for mother-tongue speech events

Motivations for BOLD

Written forms of documentation often require painstaking study to get even a phonetic transcription, as well as an analysis for orthography. In the past, many have used the oral annotation method with analog technology, but it only fulfills two of the following concerns for oral annotation:

Himmelmann's Three Concerns for Oral Annotation

- Compiling language data

- Adding native speaker comments

- Good archiving (timely and accessible)[3]

Analog technology does not remain to be adequately efficient in archiving, at least in a manner that is both timely and accessible. In response to this, Basic Oral Language Documentation (BOLD) considers an oral approach with digital recording. With digital technology it is possible to more easily maintain or improve the quality, sustainability and shareability of documentation while decreasing time spent and training required. This can all be done with a comparatively smaller budget, as well.

In an effort to further involve the speech community, BOLD aims to utilize a form of collaboration that meets the mother-tongue speakers on their own heartland. Oral processing enables mother-tongue speakers to compile and annotate their communities' own language data with minimal outside help.

BOLD Methodology

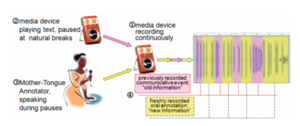

Basic Oral Language Documentation (BOLD), as proposed by Will Reiman involves the following:

- Turn on the audio recorder and leave it running.

- Play the recording of the text, pausing at natural phrase breaks.

- Mother-tongue annotator speaks and introduces comments during the breaks.[4]

Advantages

- Rapid gathering of original communicative events

- Unlike keyboarding or orthographies

- Easier engagement of the speech community

- Only requires pressing a button and speaking in their language

- Relatively rapid production of intelligible speech segments, useful for analysis and for language-learning

- Aurally and visually discernible data groupings with minimal extra cost

Disadvantages

- Without editing, approximately 70% of "WAV" files recorded contain non-meaningful 'silence' or redundant information[5]

- No word-for-word translation

- Only divided by whole phrases

- Many ways to record poorly

- It is difficult for annotators to know when to pause

- Each new text should be listened to several times to practice pausing[6]

Challenges

- Battery Life

- Many projects will take place 'off the beaten path' where electricity may be limited. Will your battery supply be sufficient for an entire recording session? You might need a supply of backup batteries, or even a solar-powered device.

- Intrusiveness of tech[7]

- Bringing large and unfamiliar technological devices to a community can be jarring and cause discomfort. The foreign objects may also elicit unconsciously unnatural behaviour from the community, so if your goal is to record naturalistic audio, it may be wise to start the work only after the participants are comfortable with the equipment.

- Audio quality

- Good quality audio ensures that the content will be usable — it can be listened to over and over again, and is more likely to stand the test of time.

- Sometimes, it is also necessary to know when audio quality should be balanced with other factors, like a naturalistic recording environment. Do you want the recording to pick up on the rustling of the leaves, or the chatter in the background? Or do you simply want an isolated recording of enunciated words? Good equipment can do either, but it is your decision as to which procedure to follow.

- Lack of settled conventions in the field

- BOLD is by no means the only methodology for recording audio, so community members and colleagues may be accustomed to another approach. Clarify, compromise, but also be flexible!

- "Edison Problem"[8]

- Dubbed by David Nathan, this addresses the fact that the field has been slow to gain appropriate skills for the level of quality now possible. Even cheap equipment can be capable of producing high quality audio, so it might be prudent to focus resources on training, as opposed to new microphones.

- The usage of data for practical purposes such as language revitalization ("'mobilizing'")

- Will your material actually be used after the project ends? Is there any way to adjust your approach so that the results may have mobilizing effects going forwards?

- The need for enhanced sensitivities and protocol in audio access and distribution[9]

- Permission is dynamic, and may change at any given moment (i.e. if an Elder whose voice you recorded passes away). Although consent may have been granted at one particular moment by a particular person, that consent may be revoked — especially years after, if the community representative has changed.

Case Study: Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea is a country which is home to over 800 languages, many with few remaining speakers, and many with minimal linguistic documentation.[11] From April to June, 2009, a team, BOLD:PNG, conducted a pilot study for the Usarufa language with the eventual goal of recording and transcribing more indigenous languages by collecting narratives, dialogues and songs. Through this pilot study, the BOLD protocol was refined and readjusted as required.[12]The project utilized three main activities:

Village-based training

Teachers, literacy workers, and other literate community members were gathered for a half-day training session in a classroom of the Moife village where they practiced using the recording equipment and were taught the oral annotation methods.

'Village-based collection and and oral annotation

The second stage involved equipping participants with digital voice recorders and logbooks for two-week periods. This included a wider cross-section of community members like elders and children, and also served as a measure for how much of the linguistic training was retained by the participants.

Town-based oral annotation and transcription

Language workers were asked to come to Ukarumpa, a more centralized Western setting, which provided a clean and quiet environment for text selection and oral annotation. As community leaders, they gave their written consent for the recorded materials to be submitted to a digital archive with open access.[14]

Findings

The Usarufa speakers had little to no difficulty operating the digital recorders and collecting material. A built-in microphone and speaker, as well as a clear display with large controls allowed for a simple recording process. Many community members were willing to be recorded, however, some spoke in a hesitant and strained manner once the recorder was actually on.

As for the respeaking process, talkers generally adopted the quick tempos of original recordings, even if they were asked to slow down to produce careful speech. If an audio segment was particularly long, speakers sometimes paraphrased or omitted words. At times, younger speakers also had difficulty deciphering and understanding texts from elders with a wider range of traditional vocabulary. Overall, however, the community speaking and respeaking process (BOLD) produced an authentic collection of language transcriptions and annotations, and the pilot study was a success.[15]

References

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 254.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 256.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 256.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 257-258.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 254-268.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 263-265.

- ↑ Reiman, D. "Will. 2010. Basic oral language documentation." Language Documentation & Conservation 4 (2009): 265-266.

- ↑ Nathan, David. "Minding Our Words: Audio Responsibilities in Endangered Languages Documentation and Archiving." Taiwan Journal of Linguistics 6.2 (2008): 67.

- ↑ Nathan, David. "Minding Our Words: Audio Responsibilities in Endangered Languages Documentation and Archiving." Taiwan Journal of Linguistics 6.2 (2008): 59-77.

- ↑ Atkey, Susan. “Basic Oral Language Documentation : Papua New Guinea.” Linguistics and Language Resources RSS, The University of British Columbia, 5 Feb. 2010, blogs.ubc.ca/linguistics/2010/02/05/basic-oral-language-documentation-papua-new-guinea/.

- ↑ “Language Documentation Prohects.” Resource Network for Linguistic Diversity, www.rnld.org/documentation_projects.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Gobinda, Chris Khoo, and Jane Hunter, eds. The Role of Digital Libraries in a Time of Global Change: 12th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2010, Gold Coast, Australia, June 21-25, 2010, Proceedings. Vol. 6102. Springer, 2010.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Gobinda, Chris Khoo, and Jane Hunter, eds. The Role of Digital Libraries in a Time of Global Change: 12th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2010, Gold Coast, Australia, June 21-25, 2010, Proceedings. Vol. 6102. Springer, 2010.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Gobinda, Chris Khoo, and Jane Hunter, eds. The Role of Digital Libraries in a Time of Global Change: 12th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2010, Gold Coast, Australia, June 21-25, 2010, Proceedings. Vol. 6102. Springer, 2010.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Gobinda, Chris Khoo, and Jane Hunter, eds. The Role of Digital Libraries in a Time of Global Change: 12th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2010, Gold Coast, Australia, June 21-25, 2010, Proceedings. Vol. 6102. Springer, 2010.